Just steps away from the heart of Lyon on the left bank of the Rhône River, in Lyon’s university district, lies a tree-lined courtyard surrounded by a compound built in the late 19th century to train doctors and pharmacists for French defense forces. The address is 14 Avenue Berthelot. Built to prepare medical personnel for the trauma of war, it became a site where occupying German forces planned, instilled and caused trauma and death during the Second World War. The compound served as home to the Gestapo in Lyon from June 1943 until 26 May 1944, when Allied bombing in preparation for the liberation of France partially destroyed the site. It was from here that Klaus Barbie, known as the Butcher of Lyon, sentenced countless Jews and members of the French Resistance to torture and death. Barbie himself personally tortured many—among them, Jean Moulin, leader of the French Resistance. Today, 14 Avenue Berthelot is the site of the Centre d’Histoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation, (CHRD), The Resistance and Deportation History Center.

On our visit to Lyon, my husband and I stayed in the city center, Presqu’ile (the Peninsula), where we walked narrow, cobbled streets enjoying intriguing shops and wonderful restaurants. Crossing the Saône on a pedestrian bridge, we explored the remarkably preserved Roman ruins at Lugdunum, part of the UNESCO World Heritage site and wandered through Vieux-Lyon (Old Lyon). It is among the most beautifully preserved Renaissance districts in Europe thanks to the intervention in 1962 by Minister of Culture, André Malraux, who saved it from destruction and made it the first “secteur sauvegardé”—protected zone—in France.

Yet I was drawn to the CHRD, across the Rhône, because of my enduring desire to understand how ordinary citizens muster the will to resist, sacrifice and survive in the face of inhumane and repressive treatment. In visiting the CHRD, I hoped to gain insight into WW II beyond dates, battles, and distinguished names from history books.

By coincidence, we were in Lyon on Victory in Europe Day which commemorates the unconditional surrender of Germany to the Allies on the 8th of May 1945. President Emmanuel Macron was there to pay tribute to the Resistance and to the memory of Jean Moulin, but public transportation was disrupted and gatherings to the parade were discouraged, so we watched the ceremony on television. We were touched by its solemnity and by conversations we had with people during the day. Memories of war endure in the collective consciousness of France, and Lyon is a particular reminder of that period as it was both a center for Nazi forces and a stronghold of the French Resistance.

Jean Moulin, who unified disparate resistance fighters throughout France and served as the first President of the National Council of the Resistance until his torture and subsequent death in 1943, is revered throughout France. In 1964, during the presidency of Charles de Gaulle, he received France’s greatest posthumous honor when his remains were transferred to the Pantheon in Paris

The day after the May 8th commemoration of Victory in Europe, we walked from our hotel, near the bank of the Saône, toward the Rhône as we headed to the Centre d’Histoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation. Along the way, we encountered striking public monuments to suffering and sacrifice during World War II in France and to injustices to humanity in other parts of the world. After traversing Place Bellecour, kilometer 0 in Lyon and the third largest square in France, we came upon a solemn and stunning permanent exhibit memorializing the Armenian Massacre of 1915, considered the first genocide of the 20th century. Installed on Place Antonin Poncet, adjacent to Bellecour, it beckons passersby with a series of 36 white columns made from Armenian stone on which are inscribed poems by Armenian poet Kostan Zarian. The site is bordered by large, evocative photographs of people and sites associated with the massacre.

On the other side of Place Bellecour, in front of what was a café during the war, stands a looming statue called Veilleur de Pierre (Stone Watchman), erected where five resistance fighters were murdered by Nazis in July 1944. An inscription entreats, “Passant va dire au monde, qu’ils sont morts pour la liberté” (Passerby tell the world that they died for freedom). The passionate simplicity of that voice through time touched us deeply.

We crossed the Rhône on Pont de l’Université, itself a vestige of the war; as were 22 other bridges in Lyon, it was destroyed by the Germans on September 2, 1944 in order to slow the American advance as German forces fled north. The bridge reopened in 1947 with the original stone piers supporting the rebuilt arches that span the river.

Entering the Centre d’Histoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation, we were welcomed by attentive staffers who spoke little English but were helpful when we plunged ahead with our less than perfect French. The headsets with English audio that we were given worked intermittently, but during our visit we encountered empathetic visitors, who, upon hearing our English, offered translations without being asked. And the artifacts and photographs in the CHRD convey powerful commentary without requiring words.

We were encouraged to start our visit with a film about Klaus Barbie. Barbie, head of the Gestapo in Lyon, was known as the Butcher of Lyon because of his brutality toward prisoners, primarily Jews and members of the Resistance. In addition to ordering the torture and execution of thousands of prisoners, Barbie personally tortured those he interrogated in savage ways, often for days on end, using devices such as spiked balls and hot needles, along with causing near drowning and trauma to open wounds to maximize pain. After the war, Britain and later America recruited him to help with intelligence to infiltrate Communist cells. In 1950 the United States helped him assume a new identity and relocate to South America, where he remained as an agent of the Americans while maintaining his Nazi ideology. In 1983 the Bolivian government arrested and deported him to France. That same year, the United States officially apologized to France for helping Barbie escape justice for 33 years.

Barbie’s trial was held in Lyon between May and July 1987. The Barbie Trial, Justice for Memory and History, produced by legal journalist Paul Lefèvre, highlights witnesses who endured Barbie’s physical and psychological torture. The film has English subtitles, so we understood the compelling accounts of those who had been brutally interrogated by Barbie or had relatives tortured and killed by him. Included in the film is testimony by Sabine Zlatin, founder of a children’s home in Izieu, a small village in the hills outside of Lyon which for two years served as a refuge mostly for Jewish children. In April 1944, 44 children, all under the age of 14, and their caregivers were arrested and sent to their deaths at Auschwitz. In her emotional statement against Barbie, who had signed the order to seize the children, she addressed the court in a broken, emotional cry: “The children, 44 children. What were they supposed to be? Members of the Resistance? They were innocents.” We were riveted by the voices of witnesses and repulsed by the smiling, arrogant Barbie. The documentary lacks artifice; it is humanity in the raw. Following the film, the audience in the small theater exited in silence. (Barbie was sentenced to life in prison. He died of cancer in prison four years later, at the age of 77.)

The light of the museum lobby and the sound of voices breaking the silence brought relief from the weightiness of the film. We were instructed to go to the second floor to begin the self-guided tour which starts with the history of the building.

The main gallery is composed of a series of exhibits that provide information about the complex and dangerous workings of the Resistance as well as insight into daily life under the occupation. A visitor may choose to follow the order of the displays, which contain primary source material such as newspapers, identity cards, ration books, photographs and posters, as well as hardware used for communication and intelligence, thus building a chronological background of the period. Others may prefer to focus on exhibits that target personal interests, pausing to contemplate or make connections with other visual and written information.

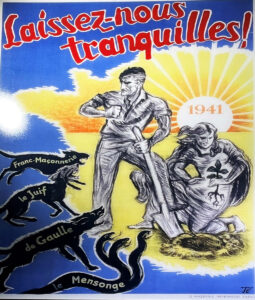

On display are materials created by the Resistance as well as those used to propagandize against it. Posters and leaflets recruiting support for the Resistance are presented next to posters hailing the Vichy government and promoting the vilest of Nazi ideology. Communications equipment, clothing worn by its members, the parachute Jean Moulin used to reenter France after meeting with de Gaulle in London in 1942, and photographs from the period create not only vivid images of war but a history of individual and collective sacrifice. It is particularly touching to see handwritten diaries and letters belonging to members of the Resistance and citizens of Lyon.

Prominent among exhibits are newspapers, flyers, and other print material effectively used by the Resistance to inspire confidence in eventual victory, to convey important information about the effort to subvert occupation, and to disseminate information to Resistance members. Compared to today’s complex telecommunication systems that instantly provide information and propaganda, this use of printed language on paper may seem simplistic. Its effectiveness, however, is evidenced by the ability of the Resistance to transmit intelligence and perform acts of sabotage while maintaining a constant presence in the public mind. Likewise, the handguns and rifles on display seem so basic compared to modern lethal technology; they support the image of the intrepid Resistance fighter as a confident armed man with a cigarette in hand. The real men, women, and youths resisting occupation and conquest, however, lived dangerous clandestine lives among the populace and assumed many responsibilities. Some fed people, hid them, and transported weapons where needed; others planned and conducted subversive attacks on German interests or dispatched information. Since there were collaborators within the population, the Resistance relied on the integrity of individuals and on munitions obtained clandestinely.

The vital role of women, accounting for between 12 and 25 percent of Resistance members, was not fully recognized until decades after the war. Women did what was needed, including transporting arms, relaying information, and hiding Jewish children. In some cases, they also took part in acts of sabotage. Because women were not as readily suspect as men, they were effective in avoiding Nazi scrutiny. I was not surprised by the suppression of the contributions of woman, but, as always, when reading history that is revised to include truth as well as popular myth, I empathized with the invisibility of such sacrifice. It is suggested that the contribution of women to the Resistance influenced Charles de Gaulle’s government in exile to grant women the right to vote in 1944.

Photographs and audiovisual testimonies add human dimension to dates, statistics, and information. The dedication of men and women who risked everything to oppose tyranny is made palpable by valuable equipment like the “Minerve” printing press clandestinely operated in Nazi-occupied Lyon to produce communiques, coded messages, and information for the populace. Likewise, guns carried by members of the Resistance underscore their constant proximity to death. The lives of those who committed themselves to saving France and to the post-war future is both inspirational and challenging. I wondered if I could have measured up to their sense of duty and courage? If needed, could I stand up to dangers threatening the world today? I found myself reading names of those captured, tortured and in many instances killed and whispering them under my breath to honor them: “Marc Bloch, Marie Besson, Daniel Cordier, Pierre Poncet.”

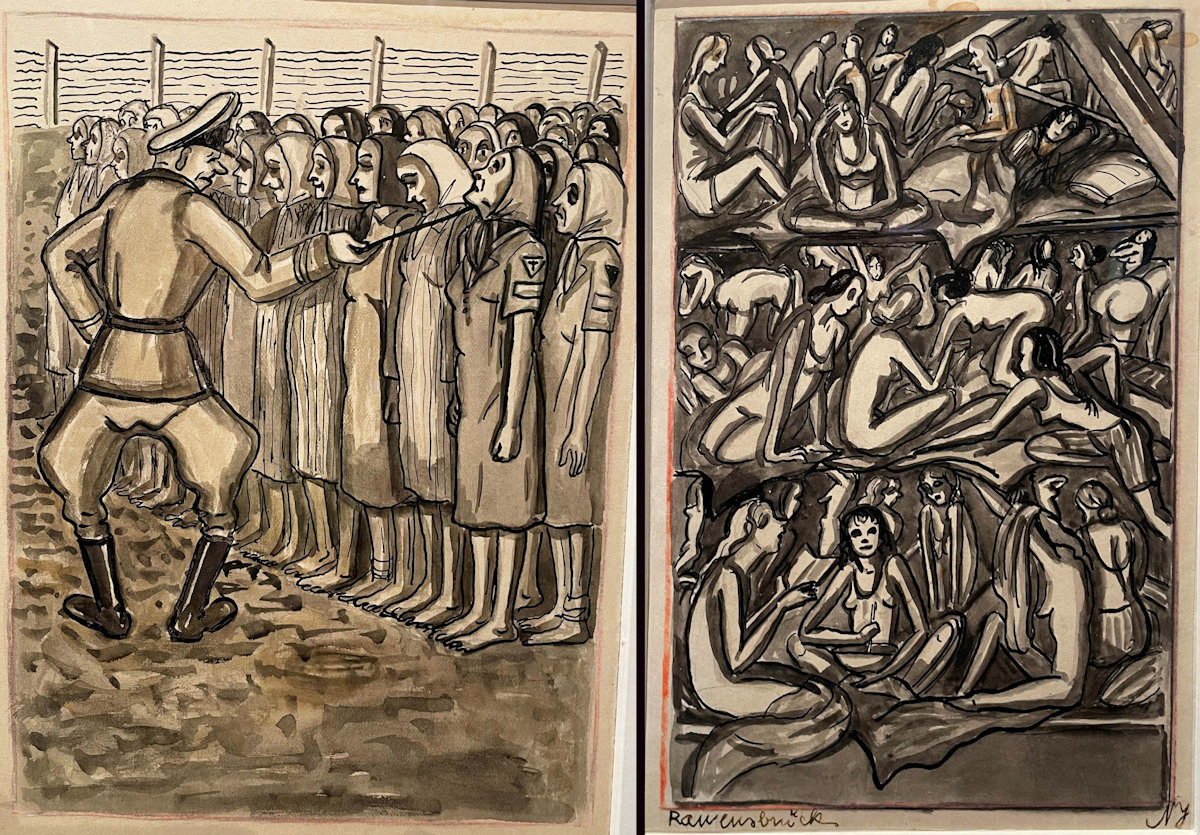

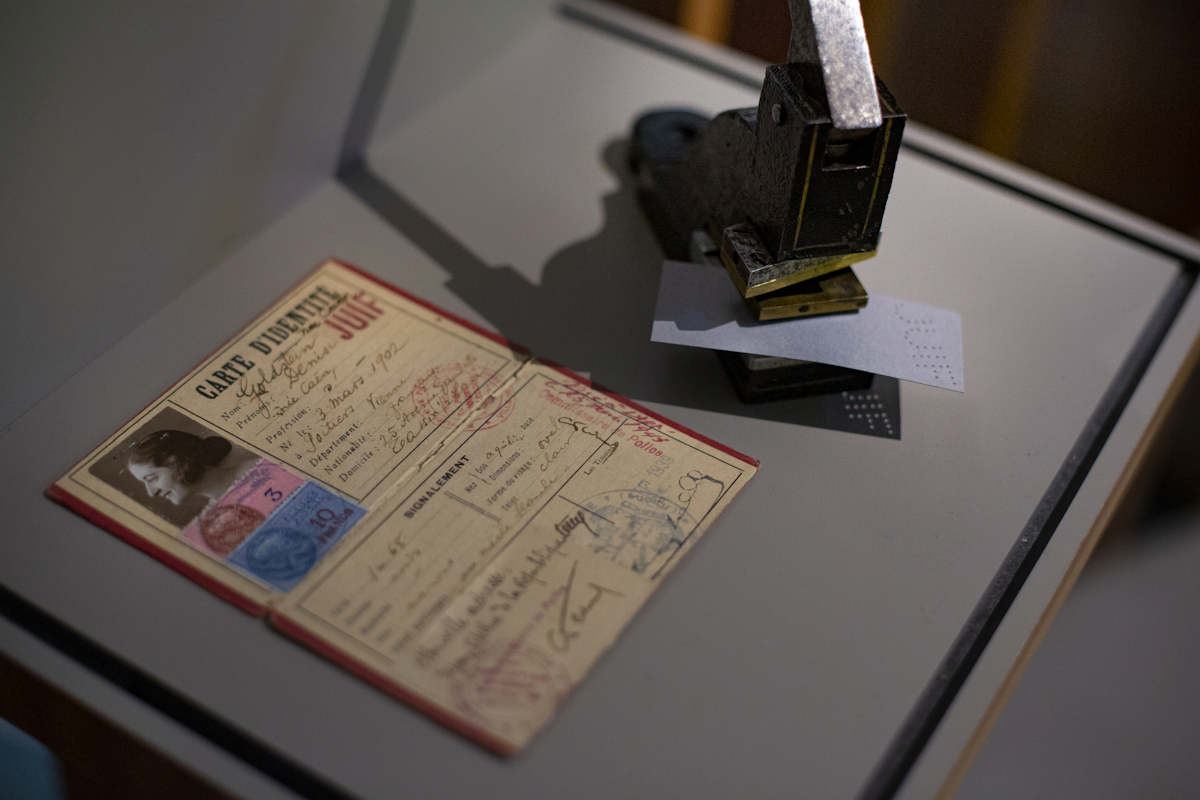

The historical narrative moves from the Resistance into a space that focuses on the capture and deportation of Jews, immediately made real by the display of the authentic striped flannel suit of a deportee interned in a concentration camp. It was donated by Jacques Micolo who kept the clothing after his liberation from captivity. Further exploration discloses detail about the Jews of Lyon and the indignities suffered as they were identified, captured, and deported to camps. Quite poignant is a series of drawings of the Ravensbrück concentration camp by Nina Jirsikova who survived and was liberated in 1945. The images depict women enduring a claustrophobic and humiliating existence, overseen in some cases by the contemptuous scrutiny of their guards. Barefoot, often naked, the women initially appear devoid of expression, but a closer look reveals identity and individuality seeking survival amid extreme depravation.

Exhibited documents include forged identity papers, leaflets announcing the roundup of Jews, a yellow Star of David declaring “Juif” (Jewish), and photographs of children and adults sent to concentration camps. Particularly poignant are objects from Ravensbrück made by captives that testify to their will to survive and reflect aspects of life in civil society. Mittens, for instance, made from a camp blanket elicit a momentary smile because they appear so child-like. Documentation on the CHRD website states they were made by an inmate as a present. How generous of the resourceful tailor to create cheerful warmth for a friend amid shared deprivation and imprisonment. Also from Ravensbrück is a multicolored deck of playing cards made by Yvonne Rochette who survived captivity.

As in the section concerning the Resistance, there are audiovisual testimonies of Jews of Lyon who were targeted by Nazis. Time spent in this sad gallery infuses painful reality into what could tragically become just a chapter in history were it not for artifacts collected and people remembered.

This section of the museum does not lend itself to random wanderings; the exhibit about the Jews of Lyon leads to a beautifully detailed dining room from Lyon in the 1940s complete with period furniture, tableware, and a radio broadcasting events of the day. We felt as if we had gone back in time to a modest apartment belonging to a family wary of every announcement over the wire and every noise from the street. There is a certain warmth because it is so homelike—despite the portrait of WWI hero then collaborator Maréchal Pétain—but it is accompanied by feelings of dread culled from the collective experience of witnessing the horror of the Barbie trial, the urgency of the Resistance, and the road to death for Jews.

This feeling was heightened when we walked down a dimly lit industrial stairwell to an austere stone basement. The effect of introducing a visitor to the fear of those captured and descending in the dark to interrogation and torture is powerful. At the bottom of the stairs, we sat on bench seats, saw a short film about the Resistance, and learned how even as individuals and groups worked against Nazis and collaborators, the leadership was documenting and formally writing concrete goals and organizational structure for a post-war government. Members of the Resistance were among the factions that helped develop the constitution and government of the Fourth Republic, which governed France beginning in 1946.

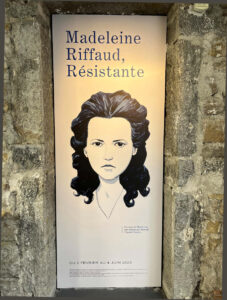

Before we left the Centre d’Histoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation, we stopped to explore a special exhibit dedicated to Madeleine Riffaud who, when only 18 years old, joined the Resistance and functioned as a liaison between units of partisan fighters. Now 99, she is one of the last surviving members of the Resistance. She famously killed a German officer in broad daylight in Paris. Riffaud was captured and tortured but upon release rejoined the Resistance. After the war she was awarded the Croix de Guerre and later become a journalist who focused on human rights. She traveled widely, reported from Algeria, and lived with the North Vietnamese resistance for seven years. She is also an author, poet, and the subject as well as coauthor of two graphic novels that tell her story, “Madeleine Riffaud, Résistante.” The CHRD used the title of her book as the name for its exhibit. Although the exhibition closed in June 2023, all past exhibits, including this one, can be explored on the CHRD’s excellent website.

Before we left the Centre d’Histoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation, we stopped to explore a special exhibit dedicated to Madeleine Riffaud who, when only 18 years old, joined the Resistance and functioned as a liaison between units of partisan fighters. Now 99, she is one of the last surviving members of the Resistance. She famously killed a German officer in broad daylight in Paris. Riffaud was captured and tortured but upon release rejoined the Resistance. After the war she was awarded the Croix de Guerre and later become a journalist who focused on human rights. She traveled widely, reported from Algeria, and lived with the North Vietnamese resistance for seven years. She is also an author, poet, and the subject as well as coauthor of two graphic novels that tell her story, “Madeleine Riffaud, Résistante.” The CHRD used the title of her book as the name for its exhibit. Although the exhibition closed in June 2023, all past exhibits, including this one, can be explored on the CHRD’s excellent website.

As my husband and I walked away from the CHRD in the late afternoon, we commented on the incisive and highly effective planning behind the exhibits. Informed by personal histories and primary source materials, we emerged with a picture of a dark and dangerous time in which individual citizens from every segment of society—shopkeepers, professionals, students—came together to be part of a local and national alliance to resist Nazi terror and help defeat it. Likewise, the horror confronting the Jews of Lyon was made real, as was their resolve to survive and maintain moral integrity.

I was drawn to 14 Avenue Berthelot because of its connection to the ascent of evil and to evil’s eventual defeat. Witnessing the Barbie trial in the place where he made decisions that destroyed so many lives reveals the long, traumatic arc of that rise and fall. Likewise, seeing the faces and names of people who recognized evil in their own time and in their own city speaks to the importance of the courageous choices they made to combat occupation and barbarism. It also reinforces the implied mission of the CHRD as stated on their website— “History, Essential to the Present.”

I am not certain that my experience enabled me to understand how people muster the courage to sacrifice and survive, but I do recognize the strength and integrity of the individual who decides that he or she can make a difference. I believe the curators of the CHRD want visitors to appreciate how defying tyranny at the grassroots level impacted the events of the war and how it led to freedom in France and the Western world. The courage and sacrifice of men and women in combatting barbarism remains with me in the faces and names I encountered in the Centre d’Histoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation.

© 2024, Elizabeth Esris. Cover image by Michael Esris.

Centre d’Histoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation(CHRD), 14 avenue Berthelot, 7th arr. Lyon.

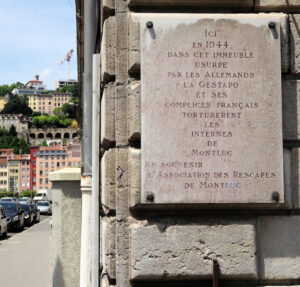

Jean Moulin, the Children of Izieu, French resistance fighters and many others were tortured or otherwise held prior to execution or deportation at the Prison of Montluc, about one mile from the CHRD. The site is now the Mémorial National de la prison de Montluc (National Memorial Prison of Monluc), which pays homage to resistant fighters, Jews and hostages who were victims of the Nazis and of France’s Vichy government, while also examining the politics of repression and persecution from 1940 to 1944. 4 rue Jeanne Hachette, 3rd arr. Lyon.

Lyon Tourist Office, Place Bellecour, Lyon.

My grandmother , Esther Bouganem (aka Boughsnem) was the tender age of 15 when the Nazis invaded Lyon in 1940! Her brother Leo and herself was placed in the convent to hide from the gestapo By her grandparents While her father Was in the city defending the town. Coincidentally her mother and six brothers and sisters were on the island of Corsica Visiting her grandmother. While my grandmother was in the attic of the convent, she got a sixth sense That it wasn’t safe there for some reason! She told her brother she needed to leave to find her mother. As I’m reading in the history books others followed her out moments before the attic was rated! Yet no one knows this little girl name! Well I can tell you her name, Her name is Esther boughanem , And we should became American citizen she changed it to Michelle Bouganem! That 15-year-old girl made her way through Nazi Europe to go to Corsica to find her mother! It took her a total of 10 years but she did do it! And what she also did, Brought her entire family to the US! And she lived the most incredible life! And one thing she always did was follow her gut instinct that saved her life! Thank you!

My French Grandmother was 14 when WWII started. She had a radio hidden in her cafe that she used to let allies know of German movements. She and a friend were late to school one day. When they arrived, all her female classmates were dead outside the school. I have more information and name of cafe and pics. She died at age 93 last year.

Michael,

That’s fascinating though it raises so many questions about what actually happened. If you’d care to send a fuller account I’d be interested in reading it.

Gary gary@francerevisited.com