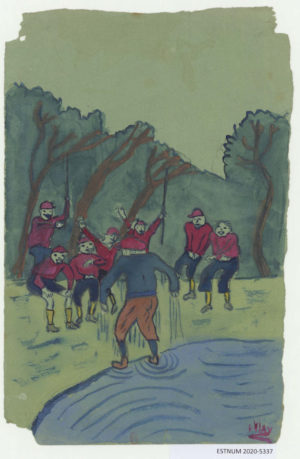

Photo above: Festivities by the fountain at the Maison d’Izieu, summer 1943. © Maison d’Izieu, collection succession Sabine Zlatin.

Relatively well known in France but little beyond its borders, the history of the home for Jewish child refugees that operated in the pre-Alpine village of Izieu from May 1943 to April 1944 provides a remarkable glimpse of migration, childhood and caregiving under perilous conditions. It’s a story—history—that can resonate well beyond France, beyond an interest in the period of the Second World War, and beyond one religious group. It is a story of humanity and inhumanity for the ages.

However worthwhile the trek, one would have to travel well off the beaten track to visit the memorial and museum that now occupies the former children’s home in Izieu, located in an isolated hillside village 45 miles east of Lyon off the route to Chambery. But now, and until July 23, 2023, an exceptional and unexpectedly uplifting exhibition at the Museum of Jewish Art and History (MahJ) allows Parisians and visitors to Paris to examine the children’s drawings and words—with a paper “filmstrip” as pièce des résistance—and to learn of the remarkable efforts of their caregivers to allow them to flourish under perilous circumstances.

The former children’s home is now officially called Maison d’Izieu, Memorial to Exterminated Jewish Children, a name that speaks of the horror that came to 44 of the children who lived there and their caretakers. Yet the title of the exhibition at the Mahj—“You Will Always Remember Me,” Words and Drawings of the Children if Izieu—speaks above all of the creativity, comradery and well-being of the children who lived there and of the devoted and caring staff that enabled it.

Though far removed from Frank family’s Secret Annex in Amsterdam, there is, says Dominique Vidaud, director of the Maison d’Izieu, a parallel to be seen between the children’s collective body of work and the Diary of Anne Frank. As with Anne Frank’s writings, the drawings, stories and letters of the children of Izieu, supplemented here by archival documents and photographs, provide an intimate and universally understandable vision of their creators in their time and place and hopes for the future.

This is not a singularly French history. In fact, what makes their story and the exhibition particularly notable is how the children of Izieu and their caregivers, as well as authorities and villagers who sought to help or harm them, reflect a much wider view of European history and of childhood and childcare itself.

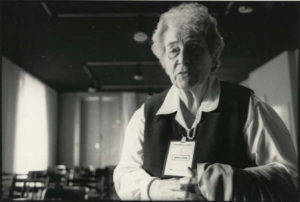

The arc holding together the three rooms of the exhibition is the memory of the remarkable caregiver and caretaker Sabine Zlatin, a woman trained as an artist who devoted herself to ensuring, during wartime and under constant threat, a form of normalcy for child refugees by creating an environment worthy of a healthy, active, developmental, educational and imaginative childhood, a survivor who went on to testify to condemn one of the prime hands of their extermination, and who spearheaded the drive to preserve their memory.

The historical context

The first of the three rooms of the exhibition presents the historical context for the existence and demise of the children’s home in Izieu. A map occupying one wall (shown below) is especially informative for visitors who are unclear of the geography of Jewish pre-war migration and wartime displacements or of the administrative borders of France during the German occupation and the location of major internment camps and of Izieu itself.

Sabine and Miron Zlatin were part of a wave of thousands of eastern European Jews of the 1920s and 1930s. Born in Russia and having lived in Poland as a teenager, Miron Zlatin (1904-1944) emigrated to France in 1924. Sabine Chwatz (1907-1996) immigrated from Poland as a young woman and reached France in 1926. They met in Nancy, in eastern France, where she was studying art and literature and he agricultural science, and married in 1927. The couple bought a poultry farm, and a decade later Miron gained national recognition in the field. Thanks to that recognition, they were both able to obtain French citizenship in 1939, shortly before the outbreak of the war. The couple had no children.

Emigrant Jews who had not obtained French nationality by the fall of 1940 or whose French nationality would be revoked were among the first in the German-occupied zone of northern France to be interned and later among the first to be deported. Yet the institution of anti-Jewish laws of 1940 and 1941 and the implementation by German occupiers and French officials of the Final Solution, the Nazi plan to eliminate Jews in territories they occupied, would eventually put Jews throughout the country in peril.

Sabine, by then naturalized French, trained and worked as a nurse with the Red Cross in the unoccupied, so-called “free” zone until hardening anti-Jewish laws caused her dismissal in February 1941. She then joined the Oeuvre de secours aux enfants (OSE), a welfare agency for Jewish children that was already active in France in the late 1930s, as a social aid to help families interned in camps in southern France and to help with the transfer of orphaned children and children otherwise separated from their family to group homes. The children in her care reflected the pan-European, as well as pan-Mediterranean, movement of Jews in the late 1930s and during the war. Most of them were born in France, Belgium, Luxembourg and Austria of parents who had previously immigrated from eastern Europe, and there were some German-born and Algerian-born children as well.

The first convoys of Jews from France destined for the Nazi death camps left for Auschwitz-Birkenau in March 1942. By July, French authorities were actively delivering Jew to the Nazis for deportation, not only adults as Germany originally requested but children under 16 as well. Whereas Jews in the unoccupied zone, though subject to anti-Jewish laws, had been largely out of reach of Nazi occupying forces, French authorities launched round-ups in the south as well beginning in August 1942. And in November that year, after American and British forces landed in North Africa, German troops took control of the formerly unoccupied zone as well, making the situation for the Jewish refugees under the Zlatins’ care more perilous. No longer safe from possible internment or deportation, those operating homes for Jewish children needed to find more secure locations. The solution for the Zlatins and others was to move to safety in the departments in the furthest edges of southeastern France, which were occupied not by Germany but by Italy.

The home for child refugees in Izieu

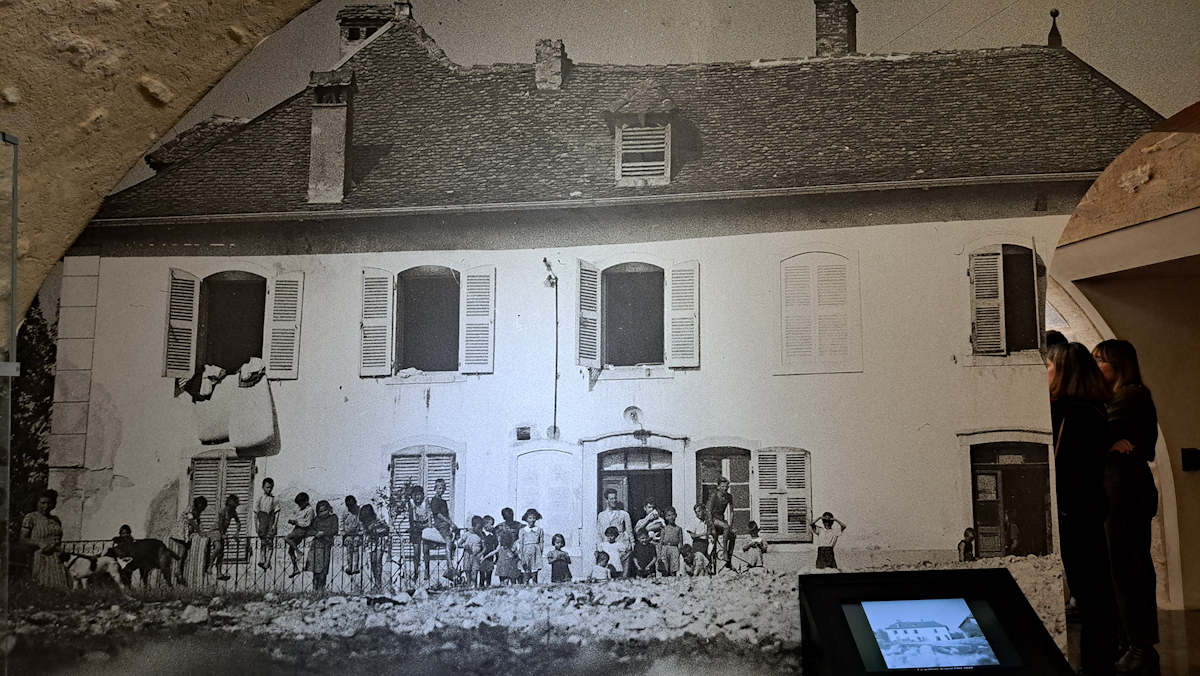

In search of a safe environment for the children, the Zaltins obtained permission from supportive French authorities (yes, there were some) in the departments of Hérault (southwest France), where they’d been living, and in Ain (southeast), where they sought to move, to occupy a large house in Izieu, within the Italian-controlled zone. Though Mussolini’s Italy had numerous parallel aims with Hitler’s Germany as a founding fellow member of the Axis powers, the Italians had little interest in applying the Nazi policies of exterminating Jews.

In May 1943 the Zlatins and a group of children left Lodève, in Hérault, to settle in Izieu. Though located in an isolated village where it would not call attention to itself, the “Colony for child refugees from Hérault,” as it was called, was neither hidden nor clandestine in Izieu. Neighbors and local authorities were well aware that it housed Jewish children and was operated by Jewish caregivers and teachers. Some villagers openly provided material assistance, and their children later told of playing with the children from the home.

The home in Izieu provided refuge for 105 children for various lengths of time during its 11 months of activity. Despite the material hardships (limited ration cards, cold in winter, lack of running water other than from a fountain outside) and while faced with the children’s the psychological and emotional trauma of having their parents taken from them, the Zlatins and staff sought to create an environment that would be as wholesome, creative and normal as possible for the children ages 3 to 16. Days were organized around schooling, domestic chores, outings into the immediate natural surroundings, preparing and eating meals, arts, craft and theater, individual (rather than collective) bedtime stories, sleep.

Instead of showing misery, the drawings, writings and photos presented in the second room of the exhibition reveal children being children: playful, imaginative, creative, laughing, mocking, singing, with an endless appetite for paper for their projects. For the children of Izieu, anti-Semitism and the war itself seemed to be kept at bay. Their drawings give no hint of current world events and lurking danger. Instead, we see colorful drawing of Puss and Boots, of American cowboys and Indians, of boys playing games, of a safari, of pleasing landscapes, of medieval tales, of valiant Cossacks. We see a list of classroom assignments for children aged 6 to 12. We see photographs that reveal outings as nature-filled as at any children’s camp, always with an air of solidarity. One senses a secular, French pedagogy.

The Gestapo raid

Yet Sabine Zlatin was aware that the situation was becoming increasingly perilous. Following the Italian surrender to the Allies in September 1943, Germans forces entered the former Italian-occupied zone of southeast France. Word came of Jews being arrested in the region. Faced with impending danger, she left for Montpellier on April 3, 1944 in search of a more secure location for the children. On April 6, the Gestapo raided the home and arrested nearly all those present: 44 children and seven adults, including Miron Zlatin. One child escaped through a window to safe hiding with a neighbor as the raid got underway. The deportation process—first to Drancy, the transit hub north of Paris, then to Auschwitz—then began under orders of Klaus Barbie, the infamous “Butcher of Lyon.” Miron Zlatin and two of the older children were killed by firing squad in Estonia. The others were gassed in Auschwitz, except for one adult who managed to escape.

Of the 60 other children who had passed though the home at various times in the 11 months prior to the raid, all but one appears to have survived the Holocaust, a testimony to the relative success of networks and of individuals protecting them and perhaps to their own fortitude. About 77,000 Jews from France perished in the Holocaust while approximately 75% of the overall Jewish population of France at the start of the war survived. More specifically 88% of French Jews, 58% of non-French Jewish and 85% of Jewish children survived. Among the survivors who had spent time at Izieu was Paul Niedermann, subject of this 2014 interview by Janet Hulstrand for France Revisited. In 1987, Klaus Barbie was sentence to life imprisonment for crimes against humanity. Sabine Zlatin testified at the trial, as did Paul Niedermann.

You will always remember me

I provide this outline of history as background for those who might not be aware of it. However, the focus of the exhibition at the MahJ is not actually on that full sweep of events. While our awareness of the arrestation and murder of the children or staff might darkly cloud our examination of the drawings and photographs, our view of them begins to be cleared by the exhibition’s emphasis on the efforts of the Zlatins and their staff to create an environment where the children under their care could develop under the best conditions possible: nutritionally, educationally, psychologically, creatively and fraternally. And our view is further cleared by the exhibition’s placing front and center the joy seen in the children’s drawings and words. They then appear luminous.

Upon her return to the site of the crime three weeks later, Sabine Zlatin gathered for safekeeping the drawings, letters and notebooks that had been left behind in the silenced house. A first commemorative ceremony was held there on April 7, 1946.

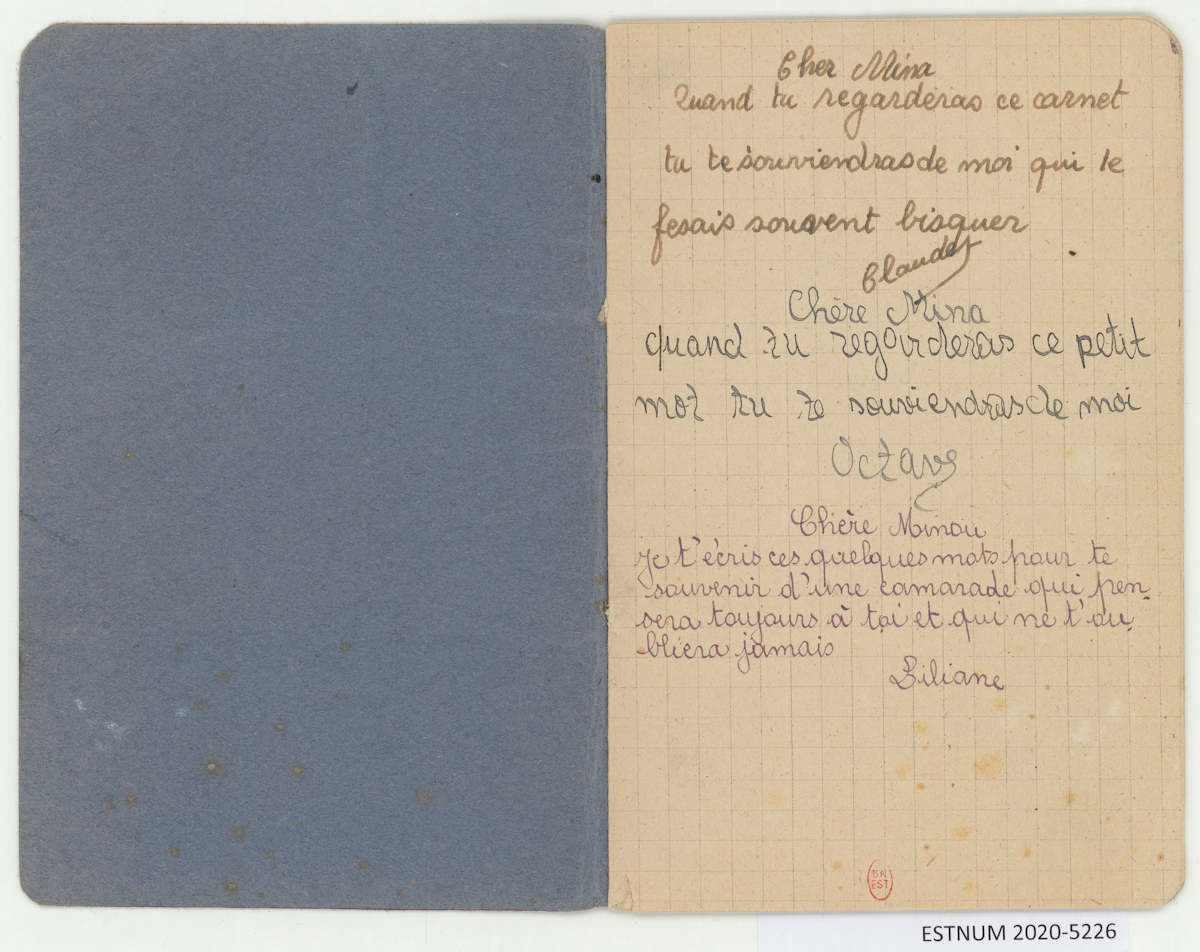

The title of this exhibition comes from a phrase that appears twice in a little notebook (below) that she found in which children wrote to their friend Mina Aronawicz as they were leaving the home while Mina was staying, as one might sign a school yearbook. Born in Brussels in 1932 to Polished parents, Mina was one of the children arrested in the Gestapo raid and killed at Auschwitz. Several months earlier, her friends wrote in her notebook: Tu te souviendras de moi. You will always remember me.

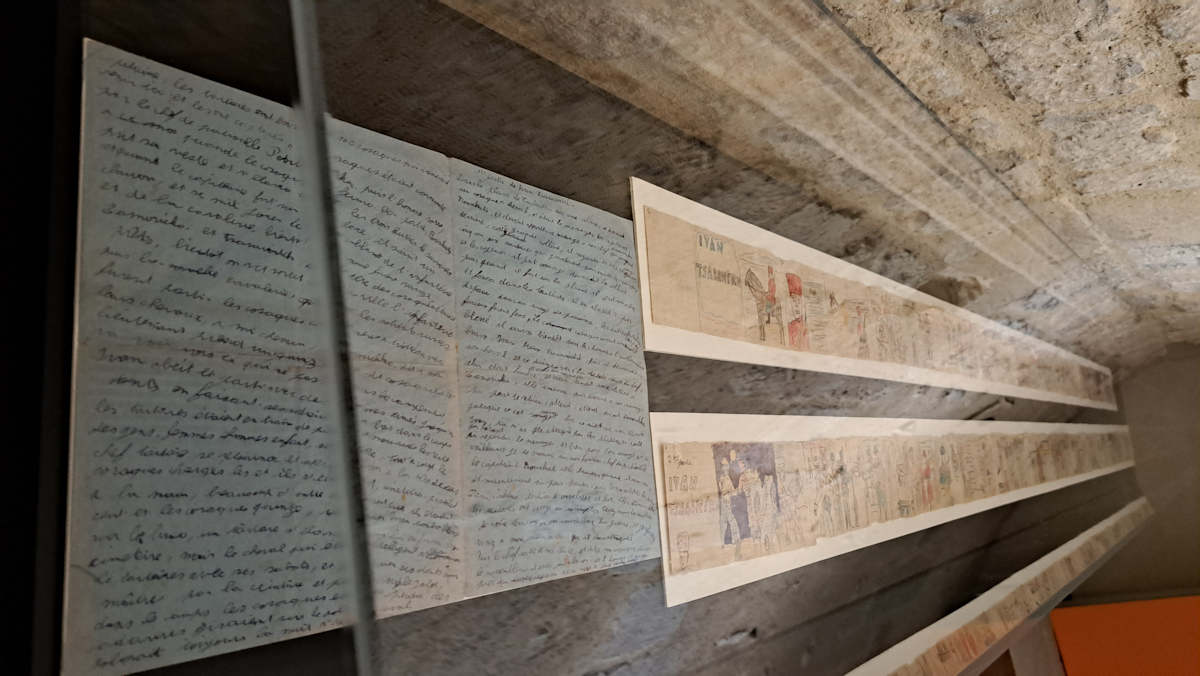

The paper “filmstrips”

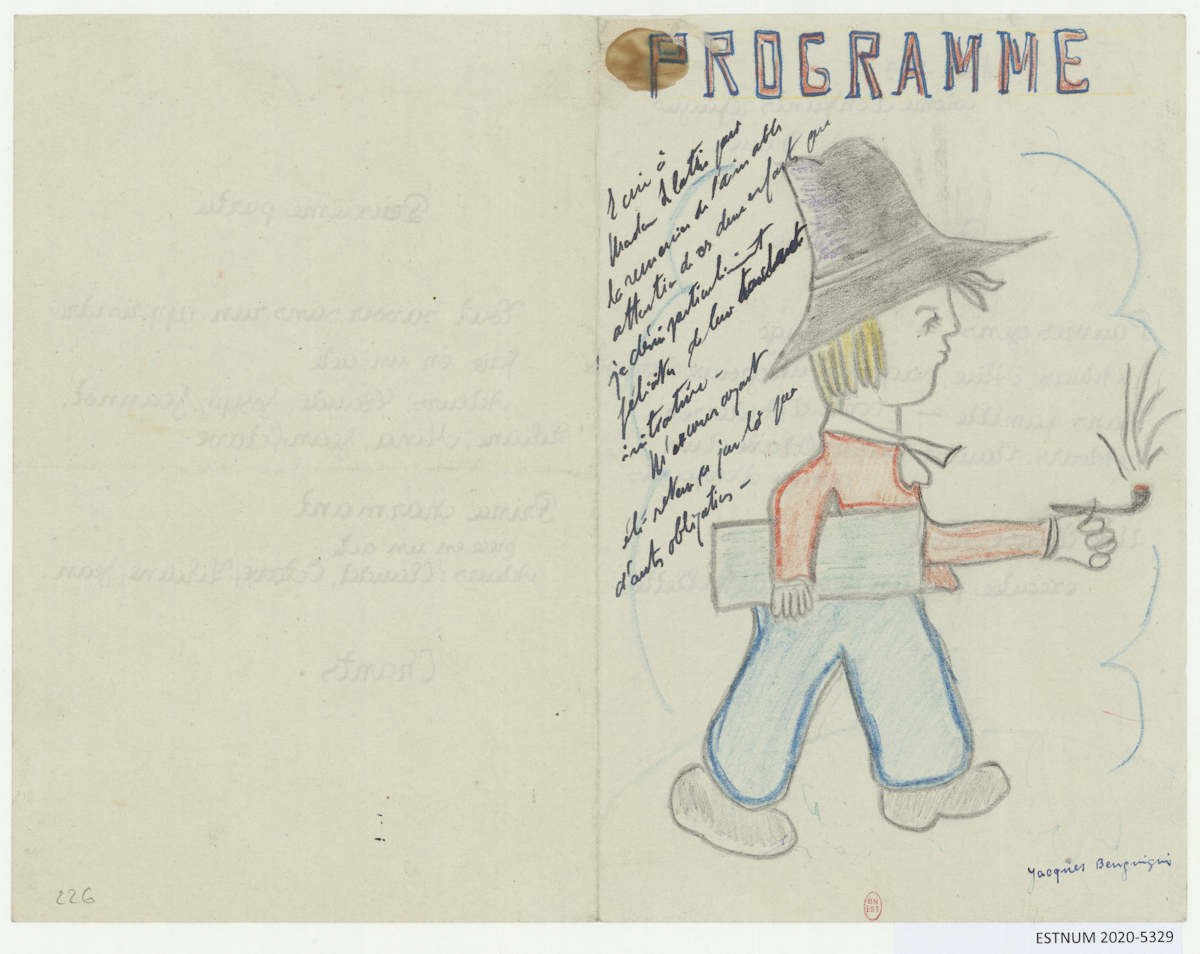

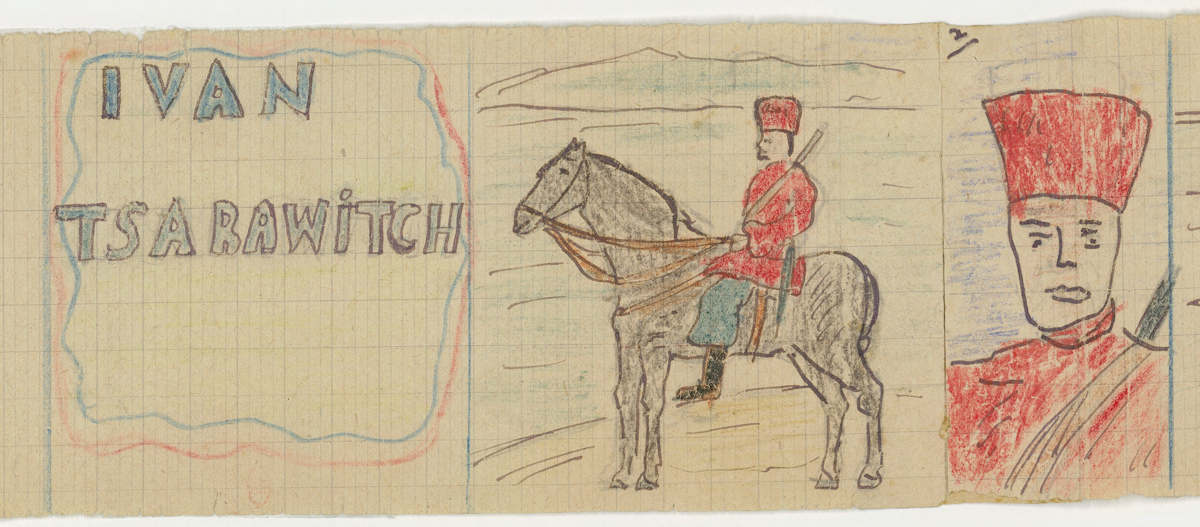

The exhibition’s third room presents the creative, collective pièce des résistance of the exhibition: three “filmstrips” made of sheets of paper glued together into long scrolls that bear crayon drawings and scenarios written by the children in 1943. The 2-3-yard scroll are fragments of paper “filmstrips” that were projected on a screen, as with a magic lantern, while the children provided the voices and sound effects to play out the scenarios they’d written.

The most complete of the three bands, Story of Ivan Tsarawitch, was recently made into an animated film. In 2021, the Maison d’Izieu asked Parmi les lucioles films, an animation studio based in Valence, south of Lyon, to work with students of the Emile Cohl Art School in Lyon to give movement to the crayon drawings. Students at the Aimé Césaire Middle School in suburb a Lyon provided the voices and sound effects for the film. Like the children of Izieu, the middle-school students were born to non-French parents and recently arrived in France. A documentary of the making of animated film can be viewed in that third room.

The film is a notable accomplishment in its own right. It also serves as a contemporary echo of the ideas, drawings and voices of the children of Izieu. The project, says Dominique Vidaud, director of the Maison d’Izieu, represents a prolongation of the work of the scroll’s original creators.

Of the other two bands, one lacks some text and the other lacks some drawings. Nevertheless, he says that with proper funding he who would like see them turned into animated films as well.

Sabine Zlatin eventually donated the saved material and other personal documents to the Bibliothèque National de France (BnF), the French National Library. “For the most part,” she said, “[these drawings] remained nearly forty-five years in my home. Carefully guarded, never looked at because too painful a memory.”

In 1988, she spearheaded the creation of the Museum-Memorial of the Children of Izieu, to which she donated other material. In 1994, President François Mitterrand inaugurated the museum-memorial at the former home in Izieu as a national remembrance site. Sabine Zlatin died in 1996. In 2000 the name was changed to Maison d’Izieu, Memorial to Exterminated Jewish Children.

Tu te souviendras de moi / You will always remember me, at the Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme (MahJ), 71 rue du Temple in the Marais district of Paris, 3rd arrondissement, until July 23, 2023. Descriptive panels at the entrance to each of the rooms are in English as well as French. Otherwise, exhibition notices are in French only but the displays themselves (drawings, photographs, documents) and their dates often speak for themselves. The exhibition is organized with the assistance of the BnF and the Maison d’Izieu, with support from the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah and the Fondation Rothschild. See here for opening times.

Maison d’Izieu, Mémorial des enfants juifs exterminés, 70 route de Lambraz, Izieu. See here for opening times. In 2023 and 2024, the Maison d’Izieu commemorates the 80th anniversary of the children’s home.

© 2023, Gary Lee Kraut

Thank you for such great and thorough article! I want to visit this during my trip to France next June! May I ask if the exhibition is in English as well or only in French?

Some descriptive notices are in English while many of the images are also self-explanatory.