Nadia Sammut , owner-chef of Auberge La Fenière outside Lourmarin in the Luberon region of Provence, is a culinary explorer with a freestyle, gluten-free approach to cooking and a holistic vision of her countryside hotel and restaurant complex. A video recording of our Culinary Conversation follows at the bottom of this page. But first, the fall.

Several miles short of Auberge La Fenière, my destination on day one of a solitary cycling tour of the Luberon region of Provence, I mistimed braking for a village speed bump and landed on the tarmac, tangled in my bike. The car coming up behind me was far enough back to stop well before reaching me. A car coming in the opposite direction slowed down and stopped alongside. The driver rolled down her window and asked if she should call for help. I stood up, pulled my bike to the side of the road, picked up my saddlebags, and told the driver that I was alright. I twisted the front wheel back straight, uncoiled and reset the brake lines, bent the mud guard back into position, and set off wobbly on the final miles to La Fenière, thinking all the way, “Holy crap, holy crap, holy crap.”

I wasn’t alright. I was battered, bleeding and my ribs hurt. Already I was late arriving at La Fenière, a property (hotel, restaurants, vegetable garden, pool) that owner-chef Nadia Sammut calls a “lieu de vie” or living space. Earlier in the afternoon, I’d lost my way—allowed myself to lose my way—on the slopes of the Luberon Massif and dawdled along its vantage points. I’d planned to arrive at least an hour earlier so as to check in, shower, speak with Nadia, then rest up before dinner. “We’ve been expecting you,” said the receptionist, and seeing my bloody forearm, “Oh my, what happened?” “A little accident.” “Do you want me to call someone? Do you want to go to the hospital?” “No, but if you have some bandages that would help.” She gave me an emergency kit with bandages and antiseptic.

Up in my room—a bright, peaceable space with a long view of the back of the property and the nearby hillside—I looked at myself in the mirror. I was banged up alright. My ribs and thigh and wrist were sore. I had three more days of biking ahead of me. Should I call it quits now? I cleaned and bandaged myself. The bleeding—rough scrapes but no gashes—would soon stop. How badly was I injured? I couldn’t tell. But I shivered at the thought of how lucky I was, aware that my fall could have been worse, much worse. (Yes, I was wearing a helmet.) I had a reservation for the second seating at the restaurant, so I napped for an hour then went downstairs.

As I reached the lobby, I saw Nadia passing through the patio dining area and the kitchen. I introduced myself and apologized for arriving too late to speak with her earlier. In the rush of dinner I had a first glimpse of her generosity of spirit. “I hear you had an accident,” she said, “Are you alright?” I assured her that I was. She said, “We’ll take care of you,” she said, “and we have all morning tomorrow to talk, if you’d like.”

Ernest Hung Do, the sommelier and maître d’, came over to my table to say hello. I told him that I’d just had a “little biking accident” and could use something strong, say, whiskey, to start. He went inside and returned with a bottle of perfumed gin. He explained how and where it was made. But rather than pour a glass, he told me that he didn’t recommend that I have it. Nadia’s meal is constructed to evolve from dish to dish, he explained, and strong alcohol would affect its proper unfolding.

“What do you recommend instead?” I asked.

“Why not just let the meal express itself and I’ll bring some wine?” he said.

“Fine,” I said, “I’d rather not make choices tonight anyway. I’ll follow your lead, and Nadia’s.”

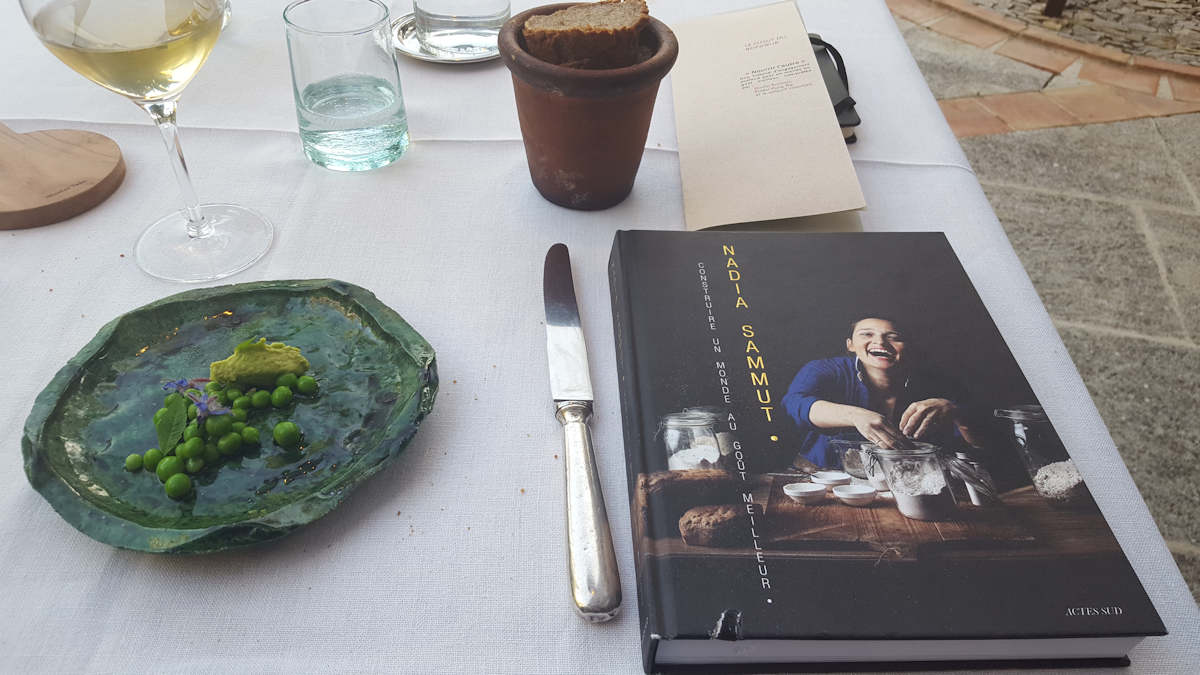

Two dozen peas and a verbena leaf

Nadia Sammut is a culinary explorer. The 12 or so dishes of the 160€ “expérience” tasting menu proceed through a fluid evolution of ingredients and textures that awaken the senses, from the intentionally bland opening to the iodized middle to the smooth finish. (There’s also a 120€ “découverte” tasting menu, but no à la carte menu.) Nadia’s quest isn’t so much to astonish, I think, but to create harmony. Ernest’s, too, for that matter; the meal was accompanied by Ernest’s coherent yet unobtrusive wine pairing.

“Precise” is how I thought of the slow parade of small dishes that evening, while “consciousness” is a term that Nadia Sammut applies to her culinary approach. The two terms meet in what appeared to be the simplest of dishes: two dozen peas and a verbena leaf the size of a daisy petal. Deceptively simple, though the full description of the dish is more complex: petit pois, crème de placenta de fève, verveine, bourrache, cardamone noire râpée, huile du domaine de Jasson. Still, I can only think of the dish as two dozen peas and a verbena leaf, and for me it lit up the patio. It was my satori moment.

Yes, it’s a dish that can easily be ridiculed: She charges how much for two dozen peas and a tiny leaf? But there you have it, the appetizer through which I realized that such culinary moments are a way of bringing one into oneself: one’s taste buds, one’s environment, one’s sense of self and of a shared meal, both with one’s table companion(s), if any, and with diners at other tables with whom you might never exchange a word. I hadn’t forgotten the physical nature of my fall several hours earlier, but I was no longer restrained by the trauma of it or by my awareness that the following day or two would reveal the full extent of my injuries. Two dozen peas and a verbena leaf allowed me to settle into the—do I dare use the word?—enlightenment of the meal, the surroundings, the evening and my travels into the Luberon. What a beautiful biking day it had been, landing me here!

No, I wasn’t cured from my fall. But I was, for the moment, soothed of it and conscious above all that it could have been much worse. (Five days later I would consult my doctor in Paris. As impressed as he was that I’d continued biking for three days after the fall, he told me that he would have recommended against it. He sent me for x-rays of my left wrist and right ribs. Turns out that I had broken a bone in my wrist, though it was the ribs, apparently without fracture, that hurt more.) But for now, I was pleased with my good fortune of feeling well enough to experience dinner at La Fenière and digesting my trauma while enjoying a precise and natural gastronomy, Nadia Sammut’s gastronomy of nature.

There are greater traumas, of course, not all of which can be soothed by kind service, a good meal and a peaceable setting. Still, all traumas need to be digested, don’t they? Linguistic aristocrats and associated snobs in France will tell you that it’s gauche to wish fellow diners a “bon appétit” before a meal; “appétit,” they’ll say with condescension, refers to the unpleasantries of digestion, which isn’t something one should mention at a polite table. But digesting one’s worries and traumas and anxieties is clearly commendable and worth wishing on one another, like raising a glass to each other’s good health. Furthermore, Nada, having dealt with celiac disease, naturally and implicitly wishes a healthy, nourishing digestion for all of her guests. Bon appétit for sure.

Gluten-free and rooted in Provence

Nadia’s “cuisine libre” (free cooking) approach, as she calls it, is neither a refusal of nor in opposition to the cuisine(s) of Provence. She remains deeply rooted in the region. Her family has lived in the Luberon for several generations. In 1972, her grandmother opened a little bistro in an old hayloft, called une fenière in Provence, in the village of Lourmarin. She then worked with her son, Nadia’s father. And when he married, his wife, Reine, learned how to cook alongside her mother-in-law. Reine Sammut eventually took over the restaurant and, in 1995, became one of the rare women in France at the time to receive a Michelin star for her cuisine. Well-known throughout Provence and beyond, Reine prepared rather traditional gastronomy. In 1996, Nadia’s parents then bought the property that is La Fenière’s current location in the countryside between Lourmarin and Cadenet. Though no longer installed in a hayloft, they brought the name with them.

At around the age of 30, between 2009 and 2011, Nadia was often quite ill from celiac disease. She says that she was basically bedridden for two years. As she explained during our lengthy conversation the morning after my dinner experience, “I said to myself, ‘This can’t be! With my culinary heritage I have to learn an inclusive approach to food that’s respectful of the environment and respect of individuals while being gastronomic and delicious.’”

She began working with her mother in 2015, soon taking the reins of Reine’s kitchen. In 2017, Nadia herself was awarded the Michelin star for La Fenière. Reine stayed with her in the gastronomic restaurant for another year, at which point, as Nadia tells it, her mother said, “You’ve got do it alone now because you have your vision, your intentions, your recipes, and it’s important that you continue to convey them.”

Though celiac disease is a significant part of Nadia’s personal story and of the development of the culinary explorations that have given her much recognition, she would rather not have her cuisine labeled solely as gluten-free. People come for the experience, she says, not for their celiac problems. Of course, there’s often a table or two where someone will speak with her about their digestive issues because they know of her personal experience. She doesn’t mind. She’s had clients who arrive in culinary distress, worried about every little thing they might eat, and she aims to calm them down. “By the second dish,” she says, “they’ve relaxed and are simply happy to be having a good meal, and that sense of happiness extends to the rest.”

Had I not known in advance that the meal would be gluten-free I doubt that I would have noticed. Presented with the chestnut bread, I thought, hmm, chestnut bread—and it was delicious—and then chick-pea bread—that too—without wondering about the absence of gluten. (Nadia operates a mill for the various flours that she then uses in her breads and other flour-based products that are served in the restaurant and available in specialty stores.) Just as one doesn’t think when eating a good piece of fish that it doesn’t taste like beef, one simply enjoys the dish. (Omnivores, by the way, drawn in by the evolution of the meal and the discovery of each small dish, might not even notice that that none of the dishes contains meat.)

“I have no obligations in my cooking,” says Nadia. “First, I don’t cook traditionally because I can’t, so for me there’s an enormous field of permanent research on plants, on living things, on the way to present naturalness and simplicity.”

Asked about her relationship with traditional Provençale cuisine, Nadia claims a clear and present affinity with it, including the techniques that she learned in part from her mother. “Provence,” she says, “has developed its culinary techniques in relation to the products that were available to work with. Provençale cuisine is also that of economy. People paid attention to what went into their cuisine; they didn’t throw anything away. Provençale cuisine is very plant-based. It’s a distinct yet varied cuisine comprised of different smaller regions. People don’t eat the same way in Marseille or in the Camargue or here in the Luberon. Its diversity is quite beautiful and should be brought to light. Its recipes, its beautiful recipes, haven’t been extinguished, and they need to be created and recreated, transmitted from generation to generation. The heart is transmitted with them, that’s a beautiful part of the energy of life.”

Regenerative and holistic

I’d arrived on opening night, so to speak, June 9, 2021, the first evening that La Fenière was welcoming diners since its 2020 Covid closing and months of evening curfew. Dining out without watching the clock was new to all of us, a time of renewal, particularly for those who, like me, prefer a late or second seating in a restaurant.

Nadia uses the term régénérateur—regenerative, something that makes you feel replenished—in speaking of the environment that she set out to create at La Fenière. That environment extends beyond the gastronomic restaurant to include the bistro on the property, the lodging, the landscape, the service, the swimming pool, the kitchen garden, the occasional activities and workshops, and the overall atmosphere. She speaks of the importance of being “conscious” of oneself and one’s environment.

“What’s essential in my life and what I think I’m able to offer others is that sense of self-awareness. To do so requires being connected to both matter and nature. And I believe that the best way to let go is to feel good, to have a sense of trust in a place, to be conscious of where one is. All that is regenerative… I like that people feel good and, beyond feeling good, that there’s a kind of interaction with themselves.”

Nadia is generous enough with her time and spirit to interact with clients if they wish, even during the meal. As she put the finishing touches on dishes in a corner of the dining patio the evening of my visit, diners would occasionally get up to see what she was doing, to ask her questions, and Nadia willingly engaged with them. She came by each table twice to deliver and explain a dish.

My most frequent interaction that evening, however, was with Ernest Hung Do, the sommelier and maître d’, a gentle, knowing, kind presence throughout the meal. Ernest came to France from Vietnam as an infant, his family having fled the country in waves of refugees known as “boat people.” As a young man, he became particularly interested in fish and became a sushi master with his own restaurant. He was named best sushi master in France one year. In 2013, he sold his restaurant since he’d become increasingly interested in all things vegetal, a move from the sea to the earth. He met Nadia’s sister, a food journalist, in Marseille, and her sister said, “You and Nadia speak the same way about food, you should meet.” That was seven years ago. They have been together ever since, as companions and as business partners. “We truly work in synergy together,” says Nadia. I asked Ernest, given his background as a chef, why didn’t he want to work alongside Nadia in the kitchen? “Because I wanted to leave her with her vision in the kitchen while presenting her cuisine and wine to clients.” He does an excellent job of it. (He credits Nadia’s father as one of his mentors in learning about wine.)

“What I do, I believe, is goes beyond the dish,” says Nadia. “I like to lead people to ask themselves questions. When you start out with something that’s bland, you ask yourself ‘Why bland?’ But what’s bland is essential for digestion, it’s essential in silence, in calm. And then something rises up, for example on the shrimp. What especially interests me is that people feel and have sensations. Of course, the dish is a part of an overall experience, and it’s essential that everything about that dish be precise. Then once you have that precision you can talk about everything else. That’s where a meal goes beyond the dishes themselves.”

Each dish grabs attention for its finesse and balance. Following the aforementioned shrimp—it was a raw Mediterranean shrimp with a squid ink emulsion, with a squid ink “chip” that nearly struck me as enlightening as the verbena leaf—the fluidity and complex harmony of a cream of bitter lettuce with an oyster in a sourdough tempura was my favorite dish. After that, the rouille in a dish called “memory of a bouillabaisse” was a discovery in and of itself.

Here’s how Nadia describes her inspiration for the penultimate dish, chickpea ice cream served with a shot of rum: “When I opened that rum a few weeks ago—it’s a friend of mine who makes it, Guillaume Ferroni, in Aubagne [near Marseille], aged in casks sometimes from Rasteau and in this case from Beaumes de Venise—when I opened that rum I said to myself, “Ah, that’s it, that’s what I want to feel,” because even though I don’t drink alcohol, just smelling it made me feel something. I don’t want sugar in my cuisine because sugar releases dopamine, which is quite different than serotonin. I want to work with serotonin, what’s called the hormone of happiness, not the hormone of pleasure. Happiness is more intense; it’s a lot more timeless. It’s something that awakens the interior of our body, not just to make us say ‘Wow’ but to make us conscious, which is much greater.”

“Wow,” is what I also said to myself when I tried the chickpea ice cream and rum. A warm honey-and-chestnut madeleine then served as an endnote to the meal.

La Fenière, a living space

Nadia’s gastronomic restaurant is the centerpiece La Fenière but there are other aspects to the property as well. Above the restaurant, in the main building on the property, there are 12 bedrooms, created in 2017. Nadia plans to develop 30 more lodgings on the opposite end of the property in the form of ecolodges. There’s also a second restaurant on the property, a Mediterranean bistro called La Cour du Ferme. There’s a swimming pool. There are hiking paths. Small-group activities are sometimes organized, such as cooking workshop taught by Nadia on Saturday mornings. Yet I wouldn’t call La Fenière a resort. It’s homier than that. There’s no grand décor, no ostentation. More boutiquish, more palatial, more photogenic accommodations are found elsewhere in the Luberon. What then to call this place?

Nadia calls La Fenière a “lieu de vie” or living space, a place of “positive living, of regeneration and of inspiration,” where guests are invited to “participate in the world in which they wish to live.” That may sound too psychic or new-age for some travelers looking to explore the landscapes and villages of the Luberon, though having stated her goal, Nadia doesn’t demand or expect obedience. She would just like visitors to slow down and be conscious of their surroundings. Thus, the hotel has a two-night minimum.

To me, La Fenière is a cultured, unglamorous countryside estate with an earthy restaurant—an earthy restaurant with an exquisite, inventive, sophisticated, earth-and-seaworthy 160€ tasting menu, but an earthy restaurant nonetheless.

An olive tree stands at the center of the patio around which, weather permitting, the tables are set. A concert of frogs played nearby as I sat at one of them that evening. As their song softened, I became aware of the sound of a bees buzzing in the yard and of Ernest’s soft steps over the paving stones. Was it a form of shock from my fall or a form of denial that I may have fractured my ribs or broken my wrist? Whatever it was, that evening at La Fenière I was one happy, regenerated, conscious traveler.

La Fenière, D943, 84160 Cadenet 84160. Tel. +33 (0)4 90 68 11 79. A 2-night minimum is required at the hotel. The gastronomic restaurant is open only when Nadia is present. The bistro remains open even when she is not. Those staying at the hotel on a Friday evening should ask in advance if Nadia will be giving a cooking class on Saturday morning. Cooking classes are also open to those not staying at the hotel.

Near La Fenière in the southern Luberon: The château and village of Lourmarin; a shaded seat in a café or restaurant by the water basin at Cucuron; olive oil tasting at Bastide du Laval; Mérindol and the history of Waldensian (les Vaudois); the 12th-century Cisterian Silvacane Abbey at La Roque d’Anthéron; the garden conservatory for plants used for dying and coloring in Lauris. Tourist information about the village and the entire Luberon region of Provence can be obtained at the Lourmarin tourist office, Place Henri Barthélémy. The Luberon is in the Vaucluse department or sub-region of Provence. For more articles about Vaucluse see here.

A Video Culinary Conversation with Nadia Sammut

Nadia Sammut was one of my guests at a France Revisited Culinary Conversation with three chefs of the Vaucluse area of Provence, along with Jon Chiri and Hugues Marrec, on June 29, 2021. Nadia appears in the introductory portion of Part 1 and then again for nearly all of Part 2. I invite you to watch at least the first 10 minutes of Part 1 in order to situate Nadia in the region and among the three chefs that I selected for this culinary conversation before proceeding to Part 2, here:

© 2021, Gary Lee Kraut

Wonderful travel writing!!! I hope to go there on my next trip.