The year was 1952. Paris was still coated in post-war grime. Lyla Blake Ward revisits her first trip to the City of Light. Featuring a 1950 Pontiac, Maurice Chevalier, Edith Piaf, La Tour d’Argent, Lasserre… and an endless drizzle. Photo above: Lyla Blake Ward in France, 1952.

… her streets were cold and gray. It was March 1952. My husband had been recalled for the Korean War and sent to France as part of a bomber wing Eisenhower promised NATO in the early days of the Cold War.

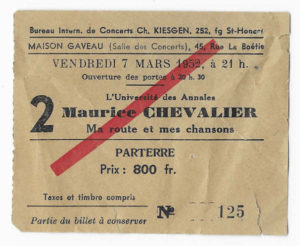

Twenty-four years old at the time, married almost a year, I arrived in the city of my dreams ready to be seduced by her warmth and historic charm. Expecting beauty and light in a city with echoes of Victor Hugo, Degas and Maurice Chevalier, we got somber darkness and bone chilling weather. We drove through grim streets, rundown houses on either side, to our hotel, a turn-of-the-century hostelry with a shabby lobby and a cage elevator. My husband had selected the one-star Napoleon Bonaparte, partly for its price, 3500 francs (about $10) for a double room, and partly for its view. The 1952 Michelin indicated that it overlooked the Arc de Triomphe. Obviously, M. Michelin had made his notes on a clear day. On this day, fog and drizzle prevented us from seeing more than an outline of that venerable monument or anything else. Looking out the hotel window, my only thought was: what was all the fuss about? I had traveled thousands of miles on the North Atlantic in February, retching all the way, to celebrate our first anniversary in this renowned citadel of love. For this? In 1952, my feminism had yet fully to emerge. Tired and disappointed, I had only one recourse. I burst into tears.

Luckily, my husband, who was also let down at his first view of Paris, had been trained for bravery in World War II. In his if-we-have-to-be-in-Paris-for-our-first-anniversary-let’s-make-the-best-of-it voice, he said, ”Let’s go out to dinner.”

We did, and even before we had our first sip of French champagne and realized it wasn’t imported, the joy of being together, wherever, prevailed. In the remaining three or four days of that first stay, although the dreary weather didn’t lift, our spirits did, and despite the gloom we started to feel some of the magnetism Ernest Hemingway or Gertrude Stein must have felt.

Notwithstanding the gloomy weather, it was heartbreakingly apparent France had still not gotten her act together. In 1952, six and a half years after the end of World War II, the grime of war coated even the most beautiful buildings, causing them to appear proud but worn. The Louvre, Notre Dame and Sacré Coeur were like elderly actors who hadn’t worked for a long time. The Champs-Elysées was only beginning to wake up with a few fashionable shops occupying some of the large storefronts that had been shuttered for many years during and after the war.

Even if I had not been wearing a bright yellow topcoat (from my trousseaux) when all the Parisian women were still in black, we would have been very conspicuous driving our 1950 Pontiac. Few Frenchmen had cars at the time, and we had ours only because the Air Force, which wouldn’t pay my way over to join my husband, was willing to pay his car’s way over. So much for family values in 1952.

Because there were so few automobiles in Paris and so little traffic, diagonal parking was allowed on the sidewalks along the Champs. Wherever we parked, we would come out to find our car surrounded with curious onlookers. The French were fascinated with American cars. People would touch the doors, the hood or the windows as if to share ownership for a moment. These observers who had no idea how our car had gotten there must have seen us as a rich American couple. Little did they know that the car was owned mostly by the bank, and the exchange rate was so advantageous that a Second Lieutenant’s salary allowed us to, if not quite live it up, indulge in a few more ooh-la-lahs than we might have at the same time in the U.S..

We could afford to eat in restaurants then we could only dream of today: Lapérouse, La Tour D’Argent, Lasserre. We could walk right into any museum or the Eiffel Tower, no waiting. We bought fine leather gloves for $5 a pair and with the purchase got a handful of samples of the leading French perfumes: Chanel #5, Arpège, Shalimar.

On that first visit, VE Day was still a living memory, and we were the symbols of liberation. We were treated with respect and admiration; the general thinking of the day seemed to be: if we were American, we had to be good. Not too hard to take for a young soldier and his bride. Rain and all, Paris had begun to claim our hearts.

The next time I saw Paris was in May of that same year. We drove up from Bordeaux, where my husband was stationed, with a windshield that had been shattered by May Day demonstrators. The Communists were expressing their opposition to the American military presence in France. Spare parts for our car were only available in Paris. Tough assignment. We had to go back.

The sun shone for the four or five days we were there. The trees were in leaf, the flowers were in bloom, the Boulevards looked Grand: the buildings that had appeared grim and sad only two months before, although no cleaner, now seemed resplendent with their softly rounded corners, balconies and mansard roofs. Lovers walked along the Seine, kissing in public. We held hands. Book stalls dotted the quays, and the Bateau Mouche had begun regular trips back and forth on the river. We were smitten. We hated to leave.

Once my husband had been transferred to Laon and we lived in nearby Soissons, 62 miles northeast of Paris, we were only an hour by train or car to the capital. Weekends, we would pack a bag, toss it in the car, and drive into “town.” Since our living costs in the small hotel where we were staying in Soissons equaled my husband’s salary (married couples without children were not given living quarters by the Air Force, just an allowance for housing) we depended on the small commission checks forwarded by my husband’s previous employer, and the favorable rate of exchange, to finance our weekend excursions. Mindful of our limited resources, we would find a small hotel, nothing as grand as the Napoleon Bonaparte, ask to see a room, check it out for fleas by shaking the curtains and bedspread, and if it proved to be insect free, check in. From here we would get dressed in our stateside finery and go out on the town to the Follies Bergère, the Lido or a small club with walls draped in dark red velvet where Edith Piaf, the Little Sparrow, sang in her sad waifish voice. Very often we would end up at Les Halles for onion soup at two o’clock in the morning before returning to our creepy but flea-less room.

By the time we were shipped back to the States, or rather my husband and his car were—I went on my own—Paris had become a part of us. Never mind the tourists who had come before. Forget those who would come after us. It was our town; our love.

The last time I saw Paris, her streets were cold and gray. It was April 2001. My husband and I had celebrated our fiftieth anniversary in March and decided to go back to the scene of our first anniversary. Remembering the weather on our first trip, we decided to wait until April. But the day we arrived was misty and overcast, and that was the best day of the week. On the drive in from De Gaulle Airport, we saw industrial plants, hotels, ordinary buildings. Except for the signs in French, we could have been entering any American city, until, all at once, in the distance the Eiffel Tower came into view, and then the street names became familiar: We were crossing the Rue St. Honoré, the Rue de Rivoli. We were at the Place de la Concorde, and suddenly we were driving over the Seine to the Left Bank. Our taxi driver took us to the Boulevard St. Germain where he turned onto a narrow street, Rue de Jacob. This is where our small Hôtel des Marronniers stood. This time I didn’t cry, but a few tears did gather as we entered the lobby and the tiny garden restaurant beyond. Because we were not alone. Having an early breakfast was our whole family: our two daughters and their husbands, and their children, our grandchildren. They had come to help us celebrate our fiftieth anniversary.

It rained off and on all week, even sleeted one day. The temperature hovered at 50; the lines were blocks long at the Louvre, the Musée d’Orsay and the Eiffel Tower. Our umbrellas dripped as we entered the Café de Flore for an aperitif. The view from the top of Notre Dame was mostly of other tourists. The banks of the Seine were flooded because of the “unusual” rain. It didn’t matter. We were here surrounded by our family. Paris never looked lovelier.

© 2021, Lyla Blake Ward, for first publication on France Revisited, francerevisited.com.

I don’t know how I missed reading this in September; what a lovely moment in time. The juxtaposition of young love and post-war Paris is very special. The Pontiac, Edith Piaf’s voice, and the gorgeous buildings dulled by grime and gloomy weather are brought to life by the image of a young woman coming to love Paris in her yellow topcoat.

I just read your article about being in Paris in 1952. I, too, was there with my husband of one year, and pregnant with our first baby, and loved it. My husband Conrad was in the Army Signal Corp and I had to head home to the US in just two weeks as he was being sent to another part of Germany. I had to save up money to be able to join him there in Stuttgart in Dec. of 1951. I have no memory of Paris looking dull or worn out. We had 65 years together and two children. Con passed away in 2016. I wish we could do it all over again. Thanks for the memory.

A beautiful piece. Thank you, Lila, and thank you, Gary!