In December of 2012, eight months after publishing the first four of an intended six-part series about hot springs and more in Auvergne, a message came through on this site in the comments section of Part IV: “I really enjoy your writing! Too bad parts V and VI aren’t up, I did want to read about Mont Dore and St. Nectaire in particular.” It was signed with a link to the commenter’s travel blog Comme Elle Baroude. Yu Jia was her name.

Yu Jia’s message both embarrassed and pleased me. It pleased me because she said that she enjoyed my writing. It further pleased me that she was interested enough to want more, particularly the more that I’d promised at the end of Part IV. “Part V: Mont Dore, Saint Nectaire and Chaudes-Aigues will be posted later in May,” I’d noted as a teaser.

Mostly, though, I was embarrassed. I hadn’t kept my promise, I’d given up, and Yu Jia was reminding me of that. I don’t remember giving up—one rarely does—but no doubt my inspiration had waned and as it did I let something distract me from the long-winded project of a 6-part series. Afterwards, I thought it occasionally, but only in passing, without the will or the inspiration to complete Parts V and VI.

Scrapbooks

Trip reports such as this Auvergne series are like scrapbooks. You sit down with pieces that you’ve collected from your recent travels—notes, photographs, audio, press kits, brochures, books—then stitch together the highlights and a few mid- and low-lights with observations, impressions, transitions and additional research. Chronology is an easy organizer. Furthermore, most of the steps of my 5-day 2012 Auvergne trip were planned in advance. I prepared and published the texts for the first four parts at a rhythm of one per week.

But some scrapbooks (and articles) don’t get finished. The scraps never get booked, so to speak; they remain in folders and the audio gets thrown out with an old computer. I’ll finish it one of these days, you say to yourself whenever you come across the folder or whenever someone mentions the place you’ve been.

Within two months after completing Part IV, I’d written articles about Kaysersberg, Colmar, Chambéry, Blois, Chateau-Thierry, a restaurant in Paris and a WWI memorial in the suburbs. I traveled; folders accumulated. And the chances of “one of these days” putting together the remaining Auvergne scraps became increasingly slim.

8 years on

It’s now April 2020, the spring of Covid-19 lockdown. That Auvergne trip was eight years ago. I’ve only been back to Auvergne once since then but nowhere near the area covered in this series. In a sense, Auvergne no longer exists. Since 2016, the official map of France has contained 13 regions rather than the 22 at the time of my visit. Auvergne has merged with the Rhône-Alpes region to become Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes. Actually, I’ve visited Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes once or twice a year since 2012, so I could fudge the facts by saying that I’ve returned to region of this series many times in the past eight years. But in all honesty I can’t. Administrative region or not, Auvergne is Auvergne, everyone knows that. The parts covered in this series have nothing to do with the Rhone or the Alps. So, no, I haven’t been to Auvergne since March 2012.

Chaudes-Aigues, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France

Saint-Nectaire, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France

Le Mont-Dore, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France

Why, then, return to this Auvergne series now?

Because in cleaning out and updating some articles on France Revisited during lockdown, I came across Yu Jia’s message. I had never “approved” it (i.e. allowed it to be made public on the site) when she wrote it in the comments section beneath Part IV. Yet I hadn’t trashed it either. Nor had I hidden my tracks by deleting the announcement in May 2012 that parts V and VI would be coming soon. For 7½ years Yu Jia’s message awaited in the limbo of the dashboard of this site, staring me down as a comment awaiting action: approve, trash or spam. It stared me down again a few days ago—”Too bad parts V and VI aren’t up, I did want to read about Mont Dore and St. Nectaire in particular”—a reminder that I still I owed Yu something. So I “approved” the message as a dare to myself to complete the series during coronavirus quarantine and began stitching and pasting together scraps and memories from my Auvergne trip of 2012.

It wouldn’t make sense to pretend now that this follows the momentum of the first four parts of the series. I’ll therefore leave the scraps in italics and place other facts, impressions, memories and comments in roman.

This is for Yu.

Mont Dore

Three types of hot springs. Living, dead, hot.

Either my guide in Mont Dore (aka Le Mont Dore) said that or that was a summary of what I’d learned about hot springs over the three days in Auvergne leading up to Mont Dore. Either way, if there are indeed three types, I don’t recall the distinction between living and hot, and I prefer the mystery of not knowing.

I’m more intrigued by another mystery: Why would you, Yu, a young woman from Singapore, still in her twenties, want to read “in particular” about Mont Dore. I can fathom an interest in Saint Nectaire—there’s the cheese and the Romanesque church. But why Mont Dore? Who’s even heard of Mont Dore, remote and bygone as it is? (Not to be confused with Mont d’Or, the fabulous and fattening runny cow cheese from the Jura region of eastern France.)

Sight of the slate roofs while approaching the hills. Le Mont Dore, at an altitude of 1000 meters. The ski slopes are 3 miles from town. The town feels unused/underused. Tourist official explains: “We’re between seasons,” nevertheless “Declining population, a town that lives from tourism and curists.”

I don’t recall the slate roofs, though I do see them in my photos. I do remember winding through hills and valleys on my way to Mont Dore from where I’d stayed the previous night near Chatel-Guyon. I remember some splendid inter-seasonal views of a choppy landscape and of lakes and hills appearing around bends or through pines. I remember above all the unused/underused feel of Mont Dore when I arrived. I remember that it brought the pleasant sense of having arrived at an oasis.

What’s especially stayed with me about Mont Dore is the thought that I’d like to settle here, or someplace like here, for a month and read and write and walk and get familiar with strangers, if they’ll let me and make the place mine for a bit. Do you ever feel that when you travel, Yu? Stopping someplace for just a few hours, do you ever think: I wonder what it would be like to settle down for a few weeks to “live” the town and explore the immediate surroundings on foot, never with transportation? Though “settle down” is the wrong term for the momentary attraction that I had for Mont Dore. “Shelter in place,” as we say today, would be more like it, within the confines not of a house or an apartment but of the entire town of Mont Dore and its surrounding landscape. You wouldn’t be there to escape anything, you’d be there… well, you’d just be there, between seasons. Then you’d want leave before too many tourists and curists arrived and transformed your quiet town. Not that you would actually ever shelter in place there. Not that you’d ever return to the place after that first visit and the original impression. But do you know what I mean?

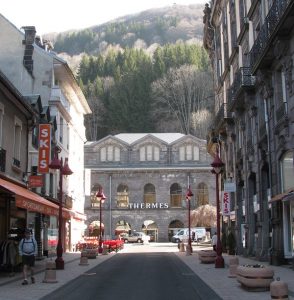

The source of the Dordogne River is just above Mont Dore. Snow-capped massif visible from town. Situated along the Roman road from Clermont-Ferrand. Vestiges of Gallo-Roman thermal baths. The current thermal baths opened in 1823, with later additions and mosaics, including a portion from 1920. The casino burned down in 1962. Eight springs, 38-44 degrees, are now used particularly for rheumatology and respiratory illnesses. During WWI, gassed soldiers brought here from the front. Hot springs exploited since about 2000 by the Chaine Thermal de Soleil, which operates 20 establishments in France. Not always water therapy, sometimes vapors are used for nasal baths and injections. The nasal infiltration room; glass canopy by Gustave Eiffel; original wall mosaics from the 1930s. No noise or movement to distract the eye as it takes in the basilica-like space of the neo-Byzantine architecture, recently restored, light from the glass black of the barrel ceiling. Villas and grand hotels. Between seasons.

I don’t remember the villas, the grand hotels or whatever building replaced the casino. But the dramatic, archaic emptiness of the hot springs complex between seasons—go for that, Yu. Between seasons.

The Dordogne and Dore Rivers meet at the foot of Sancy Mountain as the Dordogne River begins on its course southwestward before turning due west about 90 miles from here to form what most people think of when they think of the Dordogne Valley.

I’ve just looked up the population of Mont Dore. It’s been in continual decline since 1982 when there were over 2300 inhabitant. In 2019 there were 1300. How sad, an exodus, people leaving parent and relatives, unrooting themselves. Or hopeful, but with something diminished left behind. I wish them well. Let’s move on to Saint Nectaire before this trip report becomes an elegy.

Saint Nectaire

Another beautiful drive. Though I left Clermont-Ferrand three days ago on this meandering itinerary, I look at the map to see that I’m still less than an hour’s direct drive from my point of departure. Questions of near and far.

What questions? I was preparing a trip report, not an essay on distance. Sometimes one writes cryptic notes to oneself, don’t you find? With corona lockdown, everything that isn’t near seems far. I might have thought about those “questions” because Saint Nectaire also felt empty when I arrived, or because the feeling of Mont Dore was still with me when I arrived at Saint Nectaire and checked into the hotel Mercure.

But the feeling evaporated during lunch.

By contrast with the emptiness of the hotel, the busyness of the brasserie Les Baladins is a sign of a living town. I had a hearty St. Nectaire fondue for lunch. Population 728.

Lunch was more than hearty. My photo reminds me that it was absolutely and appetizingly local and delectable, the kind of meal and the kind of place where the hungry traveler says: This is good living, despite what the ingredients whisper about heart disease. (Like the pancakes, bacon and eggs on the table of the post you wrote about celebrating your 23rd birthday in Paris. But thinking about heart disease when you’re 23 is a personal crime.) To judge from the photo, I was not alone for lunch. (Neither were you for your birthday, to judge by yours.)

Saint Nectaire once had 25 hotels serving “curists” coming for ailments related to rheumatism and urinary problems. Once the cure season was over, employees would leave town to find work elsewhere, e.g. Clermont. The thermal baths closed their doors in 2004. Currently, four hotels are in operation. I’m staying in one of them. It’s nearly empty. Remnants of the 19th-century thermal baths can be seen at the Hotel Les Bains Romanes and at the Tourist Office.

Unlike other spa towns whose reputation has faded with a diminished interest in taking a cure, the name Saint Nectaire is still well-known in France because of the cheese of the same name that’s produced here and in the 69 surrounding communes. Plus, while thermalism is dead at St. Nectaire, for church hunters this is one of the prizes of central France.

A prize indeed!

You know all those great soaring Gothic cathedrals and churches of Paris and its surrounding regions, Yu? Of course you do. I saw the picture that you took from the towers of Notre-Dame on your birthday. An impressive cathedral; an impressive view. Sometimes, however, those Notre-Dames of northern France seem to me to be trying too hard compared with the ease of the rounded arches and the effortless proportions of the Romanesque period—at Saint Nectaire, for example—that proceeded the extensive use of the ribbed vaults and the pointed arches at those Notre-Dames.

On a promontory overlooking the valley (and the lower town), exquisite proportions, an impassive western façade through which one enters to the shadows of the narthex and the light of the choir illuminating the whitewashed stone and the polychrome capitals. Storytelling capitals.

Were those scrap words mine or those of the excellent guide who steered me around and through the edifice? Or were they the words of her source? Doesn’t matter: I could see it, I could feel it, from near and from far, a vast and harmonious church in such a remote area. Worth the detour, as they say in the guides.

A lengthy and thorough restoration 2002-2009.

Legend has it that Saint Nectaire, a Greek who encountered Christians in Rome then came to evangelize in this area, early 4th century, created an oratory here. Saint Nectaire said to be accompanied by Saint Auditeur and Saint Baudime. Rebuilt by Benedictine monks in the 12th century. Made with lava stone. Red, beige, blue?, grey. Belonged to the monks of La Chaise Dieu until the Revolution. A pilgrimage church, one of the 5 major Romanesque churches of Auvergne.

The question mark that follows “blue” is enough to make me want to go back to examine my doubt.

While I’d elected to focus my 5-day itinerary in Auvergne on spa towns, I can well imagine the parallel interest of an itinerary that aims for those five major Romanesque churches: Saint Nectaire, Notre-Dame in Saint-Saturnin, Saint-Austremoine in Issoire, Notre-Dame-du Port in Clermont-Ferrand, Notre-Dame Basilica in Orcival. I kept the brochure.

The treasure of Saint Nectaire is a 12th-century bust of St. Baudime, a wood sculpture covered with gilded copper. See also the Virgin and Child in the choir.

I had an appointment with Mayor Alphonse Bellonte outside the church at the end of the visit. As I write this, between the two rounds of municipal elections, Alfonse Bellonte is still mayor of Saint Nectaire.

The natural, warm welcome of this big fellow has undoubtedly contributed to my favorable view of Saint Nectaire from that day. He didn’t start, as most mayors do, by telling me anything about his town but rather about how much he’d enjoyed visiting Cleveland and Baltimore several months prior to my visit. The trip had been an extraordinary journey of discovery for him, one that he wanted to share me, an American. But Cleveland and Baltimore? Yes, he’d followed Saint Baudime on tour to those cities, and during that visit he’d marveled at the generous welcome that he’d received from his hosts.

Alphonse Bellonte is also a producer of saint nectaire fermier. Fermier (farmhouse, we would say) indicates that it uses raw milk from a single farm. Saint nectaire fermier is one of the kings of France’s farmhouse cow cheeses. Industrial saint nectaire also exists; the milk used for that can come from more than one farm and be pasteurized. The farmhouse version is tastier.

I visited the mayor’s farm, Ferme Bellonte. (Other farms in the area can also be visited.) The Bellonte family has been in the cheese business for eight generations in Saint Nectaire, and for several generations elsewhere prior to that. Ferme Bellonte is open to the public (free and daily, year-round). The farm’s 110 cows, primarily a breed called montéliarde, are milked twice each day, 7-8am and 4:15-5:15pm, followed by the cheese making 9-10am and 6-7pm, so time your visit according to your interest, Yu, or stay long enough for both. I did. (Times indicated are Daylight Saving Time, so an hour earlier in winter.)

Each cow here produces more or less about 15 liters of milk per day. 15 liters of milk for 1 round of cheese. So the farm makes about 100 saint nectaires per day. 8 days in the refrigerator then 5 weeks of cellar maturing on straw mats. Aging cellars here are 1000-year-old troglodyte quarry rooms, formerly inhabited by people and/or farm animals, which can also be visited. Summer farmhouse saint nectaire is softer and tastier.

I bought some saint nectaire fermier for lunch today. The rind, I now see, echoes the color of the exterior of the church: Red, beige, grey. Blue? I can smell (or imagine that I smell) the humid cellar and the straw on which it’s aged, though the taste of this semi-hard cheese is mild.

In addition to the spa town route and the Romanesque church route, Yu, you might also melt into the itinerary the AOP Auvergne cheese route (AOP=PAO, Protected Appellation of Origin): saint nectaire, cantal (semi-hard, pressed, raw or pasteurized, typically aged up to 6 months), salers (raw milk, pressed, aged up to 9 months), fourme d’Ambert (a mild blue) and bleu d’Auvergne (a creamy blue), all from cow’s milk.

By the way, Yu, due to the coronavirus crisis, farmers, industry and authorities have to deal with the excess amount of milk being produced in view of decreased consumption. (My Paris cheese tastings have been halted!) So the strict rules of producing an AOP saint nectaire have been modified to allow for newly cultured cheese to be frozen in anticipation of aging and sale next year. Production and storage times have also been modified slightly for blue d’Auvergne and fourme d’Ambert, as well for some cheeses produced elsewhere in France.

In the morning, breaking from the two-hour drive to Chaudes Aigues, a quick stop in the town of Issoire to visit St. Austremoine Church, the largest of the five Romanesque majors. A visual feast of its extravagant and jubilant painted columns and walls.

While the columns do indeed seem to be “extravagant and jubilant” when I look at my pictures of the interior, I must have been in an upbeat mood to jot down those words. It must have been one of those “Wow, I’m glad I stopped here!” road-trip moments before getting back into the car.

Chaudes-Aigues

The problem with scraps, Yu, and in particular my written scraps from Chaudes-Aigues, is that they amount to no more than wikifacts without footnotes. Absent some evidence that I had actually been there to “experience” the place (I put experience in quotes because what does that mean, really?), you might be tempted to skip this section. After all, your message said that you were particularly interested in Mont Dore and Saint Nectaire—not a word about Chaudes-Aigues. How then to get you to scroll beyond the fact bites?

Chaudes = hot, Aigues = eaux. The town’s inhabitants are called caldagaises.

The various springs emerge at 52-82 degrees Celsius [126-180°F ]. The 82° springs are the hottest in Europe. The village exists since about 1332, date of the construction of the first houses. We’re at 750 meters [2460 feet] in altitude. Population about 900, 3000 in summer. 1500 curists during the April-November cure season. The water at the thermal baths is 52 degrees. The water comes from 5000 meters underground. Each quarter of the village has a patron saint.

Among the 32 springs, the majority of which are private, some provide heat in winter on the ground floor of houses, about 20 of them. Those whose homes are heated with the hot spring pay only an annual maintenance fee of 30-100€, depending on the length of the piping network and the temperature. Pipes get clogged with deposit; they need to be cleaned often, eventually replaced. The church is heated this way as is the municipal swimming pool. The springs also feed the thermal baths (expanded in 2004), the fountain (where I boiled my egg) and the lavoir (publish wash basin), which is still used and where the water, which contains sodium bicarbonate, is good for bleaching.

Before 2004, about three-quarters of homes were heated by the spring called Source du Par. Since then, three-quarters of the flow is used by the thermal center and for the swimming the pool from June to September (through a spring water serpentine) + to heat the church (to 20-25°C/68-77°F) + to boil my egg. The little Geothermalism Museum explains how houses were/are heated and shows pipes that get obstruct quickly with carbonate deposits and must be cleaned frequently.

On your blog, Yu, you define yourself as a baroudeuse, an adventurer. I don’t think of myself in the same way; I’m not a baroudeur, just someone who travels sometimes, happy enough with the adventure of boiling an egg in the fountain made at a hot spring in Chaudes-Aigues in Auvergne.

Centre Caleden, thermal center that belongs to the Cantal department in a new building since 2009. Includes thermal baths, spa, fun pool, hotel, residences. Water comes out at 32-37 degrees depending on where. The average age of those who come for the cure is 65, often “retirees and professors.” The cure lasts 3 weeks, prescribed by a doctor, with 60-100% reimbursed by the Sécu [the French health system]. 230 curists come in the morning, fitness program clients then come in the afternoon.

Lunch with Claire Soyer Le Thorel, director of the Chaudes-Aigues Tourist Office at owner/chef Simone Gascuel’s Le Moulin des Templiers, in Jabrun, a 10-minute drive from Chaudes Aigues. SG’s mother ran a café here in what was formerly a mill, rebuilt after WWII. Her father wanted her to work in the kitchen. [Now there’s a line that’s open to interpretation! It means nothing to me as I read it now; I assume that it meant something to SG if she said it to me. What did your father want you to do, Yu? Mine wanted me to be a doctor. He also liked to travel.] My first encounter with Le Birlou, an apple and chestnut liqueur that smells like apple and tastes like chestnut. Salade de gesier, blanquette de veau, pruneau au vin rouge.

That’s it, Yu. I left Chaudes-Aigues soon after that for the Aubrac Plateau. My article about that, the sixth and final part of this series, will be published soon. I promise.

In the meantime, I have a question for you, Yu. After your two-year stay in France and the celebration of your 23rd birthday in Paris with pancakes and gargoyles, you visited over the following year New York, Quebec, Nova Scotia, Malaysia and Montenegro. A barodeuse indeed! Then you were in Istria, Croatia, taking your time before “the drive back to civilization.” With that line you ended your blog. Did you ever make it back?

© 2012, 2020, Gary Lee Kraut

Return to:

Part I: From Paris to Clermont-Ferrand

Part II: An Introduction to Spa Towns and Hot Springs By Way of Royat

Part III: Chatel-Guyon

Part IV: Château La Canière, a Luxury Hotel

This was awesome. Really. I’ve never read a travel article like it before.

Thanks you, Kylowna.

Much appreciated.

Gary

I’m very pleased to hear about you and to read about Chaudes-Aigues 😉

Thank you for this article and for visiting us.

Sincerely,

Claire Soyer Le Thorel