American photographer Quinn Jacobson, a specialist in early photographic techniques, has returned to Paris this spring with “The American West Portraits,” a showing of recent works at the gallery Centre Iris pour la photographie until June 19, 2012.

The portraits in this show were created with the wet plate collodion process, a photographic technique developed in the 1850s that corresponds well with what Jacobson calls his “preoccupation with otherness.”

That preoccupation was more apparent in the haunting portraits presented in his 2010 show “Glass Memories” at Centre Iris, just north of the Pompidou Center (see map below), based on the same process.

In “The American West Portraits” the otherness is less in the foreground, less in-your-face. Perhaps that’s because while “Glass Memories” was partially realized in Germany, where Jacobson, originally from Ogden, Utah, had expatriated himself and his family from 2006 to 2011, “The American West Portraits” reflect a homecoming.

Last year the photographer left Viernheim (Hesse), Germany and moved to Denver, a city he says he selected among a hatfull of western cities.

During an interview prior to the March 14 opening of the new show, Jacobson said along with the culture shock of returning to the U.S. after five years in Europe he was struck the diversity of people in Denver.

While French viewers are undoubtedly drawn to the exoticism of the American West, not only because of distance but because nation-building through frontier settlement has no equivalent on European soil, American viewers will find some familiarity in these new portraits; we recognize in them characters from the 19th-century western town of our own imagination, circa 1876, say, the year Colorado joined the Union.

The wet plate collodion process results in singular images on either glass (ambrotype) or metal (alumitype or ferrotype). Created with a 150-year-old technique, these brownish-grey portraits naturally give the impression that the subjects lived in another era. That impression is reinforced by Jacobson’s eye for and attraction to individuals on “the fringe of society.”

Another factor may well be at play: whether on the fringes or in the center, society—in this case Denver society—is undoubtedly formed of many of the same elements in 2011 as it was in 1876.

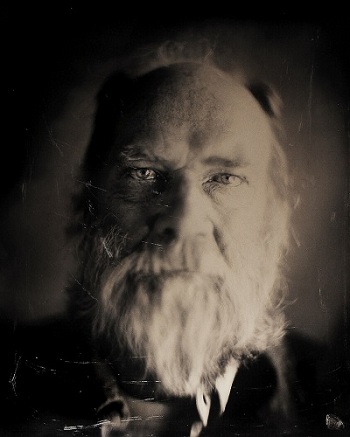

This, for example, could be the portrait of a cattle rancher come to town on business, though the title reads “Cannabis farmer”:

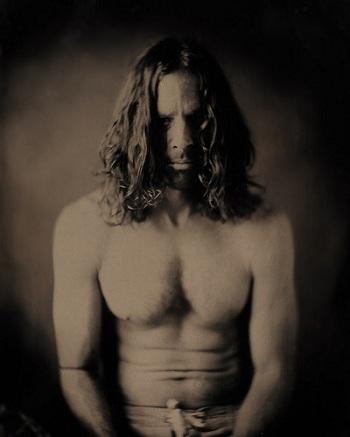

This could certainly be a character from post-Gold Rush Denver:

This could be an outcast in any age, or perhaps a man on his way to the gallows:

Sitting for portraits, Jacobson says, his subject do indeed imagine themselves in 19th century photography and positions, such as a fiddler holding his instrument like a rifle. Strangely, it’s only a blind woman who is clearly from a more recent area due to the fluffy light-colored blouse she’s worn for her portrait. Otherwise, the portraits can be transposed to the Wild West, even if their titles clearly place them in the present, such as “Rap promoter” or “Jewish punk rocker.”

Kyleigh, who seems to be one of Jacobson’s muses in this recent work, appears several times in this exhibition. Drawn down by dreadlocks, her gaze, having been held still for a full six seconds to fix the image, could be either that of a turn-of-this-century middle-class child gone Rasta in rebellion or that of the 19th-century daughter of a Scottish settler and an American Indian. Either way she appears to be waiting to discover who she is or who she wants to be. The largest of her portraits is hung at the far end of this basement gallery, as though at the focal point of a grotto chapel.

The basement exhibition space is well adapted to Jacobson’s work and their appearance of found artifacts of another era.

Quinn Jacobson gave a demonstration of the collodion technique prior to the opening and will be giving other workshops and photographing individuals at times during the run of the show (see schedule below). Watching him prepare his subject, introduce plates, count the seconds of posing time, pull out vials of his chemical mixtures, pour liquids onto the plates, and heat them to the point of nearly burning his fingers, comment on the serendipitous nature of the technique, and hearing him tell how he came to love one of his glass plate portraits that had been accidently shattered to many pieces that were then put together, it is clear that Jacobson is not a point and shoot kind of guy.

He cites the visual, olfactory and tactile aspects of the process as elements that can “reengage people with the craft of photography” and bring about “the personal connection that’s missing today.

He nevertheless willingly allowed this writer to photograph him in instant pixels.

From collodion to daguerreotype

With this show, Jacobson brings an end to his personal evolution in working with the collodion process.

“After ten years in collodion I have nothing more to say about it [in my work],” he said. “It’s run its course.”

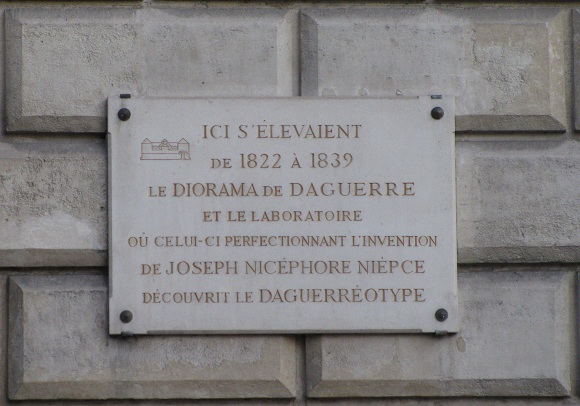

His interest has now turned 15 years further back in the history of photography to daguerreotypes, named for Frenchman Louis Daguerre, who perfected his technique in 1839.

Since 2010 Jacobson has been working increasingly with in “authentic mercurial daguerreotype” and will largely devote himself to that for the foreseeable future.

In 2014, the 175th anniversary of the year Daguerre perfected his technique, the Centre Iris will be hosting a show of Jacobson’s daguerreotypes. The gallery is just half a mile from the site of the laboratory where Daguerre developed his technique by what is now Place de la République, as indicated on this plaque.

“The American West Portraits” by Quinn Jacobson at the Centre Iris pour la photographie, March 15 to June 19, 2012. 238 rue Saint-Martin, 3rd arrondissement. Metro Arts et Métiers. Tel. 01 48 7 06 09. Open Tues.-Sat. 2-7 p.m. Free admission. Prices of these single-sample works run from 600 to 5000 euros.

Quin Jacobson’s Workshops: Jacobson is running five 2-day workshops in English initiating participants in the wet collodion process on March 19 and 20, March 21 and 22, May 30 and 31, June 5 and 6, and June 7 and 8, 650-725€ per person. Contact Centre Iris for more information.

Back in Denver he gives workshops at the Colorado Photographic Art Center.

Your collodion portrait: Individuals can have Quinn Jacobson create their own one-of-a-kind collodion portraits—“handmade artifacts,” he calls them—on glass or metal by signing up in advance for a 30-minute photo session on March 13, 15, 16 and 17, May 29, June 4 and 9. Cost 160-235€ depending on size.

Explaining the wet plate collodion process: Jacobson explains the process, followed by a video demonstration here.

Quinn Jacobson’s website: Studio Q.

© 2012, Gary Lee Kraut

Beautiful work Quinn. I especially like “Kyleigh.”