Travel writing can be solitary work, but a travel writer with a cat needs friends.

I used to leave my chartreux Moumoon with Isabelle, but whenever I returned to Paris her daughter would cry that I was stealing her cat. Carine would be willing, but she doesn’t care for cats; once or twice she did keep Moumoon, but waking up to his steely stare from the head of the bed creeped her out. Jean-François would be willing, too, but he creeps Moumoon out since Moumoon associates Jean-François, who also happens to be his vet, with needles and pain. Henri is allergic, so is Pascale’s son. Jean-Pierre travels on business for weeks at a time. Mahinde would gladly help out as long I don’t go away too long—but I do.

So for several years I entrusted Moumoon with Olivier. Olivier is one of the most reliable people I know. Furthermore, he loves Moumoon. He loves him so much that he often tells me that I’m a bad pet owner for abandoning him as often as I do, that I don’t feed him the right nibbles, and that I should go a different vet.

Olivier is also one of the most negative people I know. As friends, Olivier’s rigid pessimism and my casual cheer led me to play Lippy the Lion to his Hardy Har-Har; I would come up with ideas for jump-starting our respective careers (he is a graphic artist and designer) and he would come up with a hundred reasons why not to bother. For a while, actually for two whiles, Olivier was unemployed, having worked for a small company that went belly-up and then for a second one that did the same, which only encouraged his natural negativity.

He used to live in my neighborhood, so we would often get together for coffee or for dinner or to go biking. Then he moved into the 19th arrondissement, which is just a few metro stops away but is far enough for us to meet less often. During the second while of his unemployment Olivier’s grousing became more embittered and I got increasingly tired of listening to it. It was always the same people—those with money or with power, their children, their friends, and assorted liars and cheats—who got what they wanted. His complaints were tough enough to endure when they involved his own life, but intolerable when they involved mine. My slipshod approach to freelance work and to finances disturbed him to no end. I saw him less and less.

Then one day I thought I would do us both a favor by hiring him to help with the design of my website. He was actually excited by the idea. So we met for lunch, and there, in the midst of my Lippy the Lion presentation of the project, his critical nature got the best of him. Little by little he tore every idea apart before concluding that my work was worthless and my graphic sense was worse. I said that I would deal with the work part and that I had no pretensions about my graphic sense, which is why I was soliciting his help. But he insisted. With his underpaid help, he said, the graphics of the site would be good, but the rest of it would still be rubbish, so maybe it wasn’t worth the effort.

I told him to go to hell.

I wanted nothing to do with him after that. Remembering his qualities didn’t seem worth the effort. I wrote him off as the classically depressed Frenchman who blame his woes on government and religious or ethnic communities, believing that complaint is man’s most honorable intellectual exercise.

***

Two months later I got the Call. Not the awkward call from a former friend asking how you’ve been but THE Call, the one from a family member telling you that there’s been an accident and that you need to get on the next plane home.

Henri came right over, followed by Jean-François. Corrine brought comfort and food, Mahinde brought more. Pascale called from India, Jean-Pierre from Lourdes.

Then I called Olivier.

“What do you want?” he said.

“My brother and his entire family just died in an accident. I’m leaving tomorrow morning. I don’t know when I’ll be back. Will you take Moumoon for a while?”

“Alright, bring him over.”

“Can you come get him, I don’t have time.”

There was a pause.

I said, “Can you take him or not?”

He did.

In the following year I made frequent trips to the U.S. to deal with estate matters and to be with family, always for a month or more. Each time I called Olivier to ask if he’ll take Moumoon. The first two times I called him several days before I was planning to leave and our conversation went something like this:

“I’m leaving again on Thursday, can you take Moumoon?”

“You’re using me.”

“It’ll do you good to have company.”

“Why don’t you ask Jean-François or Carine or Henri? They’re your good friends.”

“Yes or no?”

“For how long?”

“Five weeks.”

“Five weeks!? Poor cat.”

“Yes or no?”

“I’m only doing this for Moumoon.”

Like divorced parents who manage to get along for no more than three minutes every other weekend, we would then meet to make the exchange.

My view of Olivier has softened since then, partly because I’m aware that I’m using him, partly because he began speaking less like a victim. He was going into business for himself. After 18 months of unemployment, he planned to open a flower-and-deco shop in the fall.

We even called each other a couple of times before my last trip. I asked how his plans for the shop were coming along, he asked about my family, about estate matters, and about Moumoon, and I told him when I’d be leaving again. He still reminded me that I was taking advantage of him, to which I snidely remarked that he could use the company. But now I also said that I was looking forward to seeing the shop. And since the shop was near my apartment, he was also offering to water my plants. (Unlike Moumoon, my plants actually seem to have a masochistic appreciation for drought.)

I intended to stay in New Jersey for four weeks the following winter but didn’t return for six. I went to Olivier’s apartment the day after I got back. He was in an unusually upbeat mood. He didn’t even accuse me of being a poor pet owner for staying away so long. All he reproached me for was not putting the word out to my friends that he’d opened a shop. He gave me the receipts for cat litter and food, I paid him, stuffed Moumoon into his cage, and told him that I would stop by the shop soon.

***

Two blocks from home I came across the woman who, with her husband, cleans the common areas of the small apartment building where I live. They also clean two neighboring buildings. Monsieur and Madame—I don’t know their names—are from Portugal. In the seven years I’ve lived in this apartment I’d never seen Madame so far from my building. In fact, we’d never exchanged more than chirpy bonjours in the stairwell, with the occasional comment about the weather and the wet floor.

Meanwhile, Monsieur and I have become sidewalk buddies over the past few years. We tend to meet at about 6:15pm when I’m coming or going and he’s waiting by the curb for the garbage truck to pass to empty out garbage bins. We speak about recent events in the building or in the neighborhood: about the time a chunk of the cornice fell off the building, bounced from the awning of the restaurant downstairs, and smashed the windshield of a parked car; about the time they took away the old neighbor on the second floor who’d lost his mind; about who might have tagged our hallway; about why I’ve had to change the inner tube of my front bicycle wheel three times in the past year; about the homeless men camping at the end of the street. Monsieur is a short, gentle, talkative man. He looks both ways down the street then takes hold of my sleeve when he wants to tell me something important, such as the price the apartment was sold for on the fifth floor. He is my most constant friendly contact in the neighborhood since Olivier moved away. He actually notices when I’ve been gone for a few weeks, and I’m nearly jealous when I find him speaking on the street with one of my neighbors, who will look at me not as though I’ve been away but as though I never lived here.

Monsieur’s accent in French is thick, the words often mumbled, and the conjugations approximate. I wasn’t aware of how much smoother Madame’s French is than his and of her cheerful twang until I came across her that recent morning as I returned from Olivier’s with Moumoon.

We passed each other and exchanged a Bonjour Madame-Bonjour Monsieur, but one step later she stopped and said, “You have a cat.”

I turned to her, held up the cage, and said, “Yes.”

She peered inside. “He’s beautiful, is he a Persian?”

“No,” I said, “a Chartreux.”

“Oh, they’re wonderful cats,” she said. “I never knew you had a cat! We used to have a cat—not as beautiful as yours, un chat de gouttière–just an alley cat–mais avec les chats on s’attache, vous ne trouvez pas?–but it’s easy to get attached to a cat, don’t you find?”

“C’est sûr,” I said, one does indeed get attached to one’s cat.

“How old is he—she?”

“He. Seven.”

“How old was he when you got him? Ours was five. We adopted him from the street.”

Before I could tell her that Moumoon was one when I got him she launched into the story of her alley cat. It was a long urban tale involving a homeless male, doorstep feeding, cautious invitations inside, definitive adoption and family life.

I listened, but I wanted to tell her about Moumoon, how initially I hadn’t wanted a cat. I wanted to tell her that prior to having Moumoon I’d thought of cats and dogs as outdoor pets, as none of the animals we’d had when I was a kid lived in the house with us. Sharing my apartment with a cat once seemed as absurd an idea as sharing the house with one of our goats. Furthermore, whenever I’d been offered a cat I’d thought that having one would be bad for my image and, worse, for my self-image. I didn’t want to be a cat man. In graduate school I’d rented a room in the big, scantily furnished house of a cat man. He raised free-range show cats: long, thin, constantly whining Blue Point Siamese and evil, hyper Cornish Rexes who occasionally got closed into an empty spare bedroom with a hired lover. From my bedroom in the attic I would hear the growls and complaints of refusal, seduction, coupling and withdrawal. When the cat man, who also worked as a buyer for a major department store, went out of town for work or for a show, I would feed the cats. Once, going away for a week, he asked me to give daily medications to several of the kittens, which meant chasing the hairless creatures around the house and into my landlord’s bedroom, dragging them out from among the porn magazines under his bed, and getting bitten and clawed as I tried to shove a pill down their otherwise stranglable little throats.

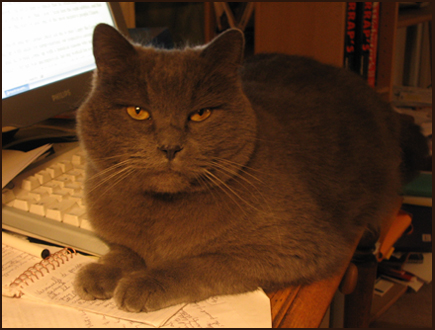

I had no intention of becoming a cat man myself when my friend Didier asked me six years ago if I would take his cat Moumoon, a name given by Didier’s autistic 11-year-old son Jeremie. But something had to give in the menagerie of their apartment crowded with another cat, a dog, guinea pigs, parakeets, and several tanks of tropical fish. I don’t want your cat, I told him, but the next day Didier showed up at the door with Moumoon in his hands, not even in a cage. I agreed to keep him for a few days until one of us could find another solution. So I ran out to buy a litter box, litter and food while Moumoon went into hiding. When he finally emerged two days later, I realized that I was caring for the most beautiful, intelligent, responsive and affectionate cat that had ever lived. Furthermore, seeing him perched by my computer with a paw over the mouse, I understood that as a writer having a cat wasn’t so bad for my image, self or otherwise, after all.

But I couldn’t tell Madame any of this because she was still recounting her own cat story. Occasionally she would stop to crane her neck toward Moumoon’s cage, then say, “Where’s his vet? Ours was on boulevard de Magenta” or “Oh look, he’s sticking his paw out, he wants to shake hands!” or twice “That’s funny, I didn’t know you had a cat!” And then we were off again on the trail of her adopted tom with scratched armchairs, dead mice on the doormat, near misses alongside speeding cars, frightening gutter walks, illness, aging, and expensive visits to the vet (mais quand on aime on ne compte pas). When finally she told me that they had had to put the cat to sleep it wasn’t with sadness or even nostalgia but with communion, for her cat tale didn’t end with the death of a pet but with her comment, once again, “I never knew you had a cat!”

She repeated it, I think, not only as an expression of her discovery that I, too, like cats but that by consequence I must be a decent, caring human being, the kind of person one would be pleased to know.

“It must be difficult having a cat since you travel a lot,” she said.

“A friend of mine takes care of him while I’m gone.”

“He must be a very good friend,” she said.

“He is.”

© 2007, Gary Lee Kraut