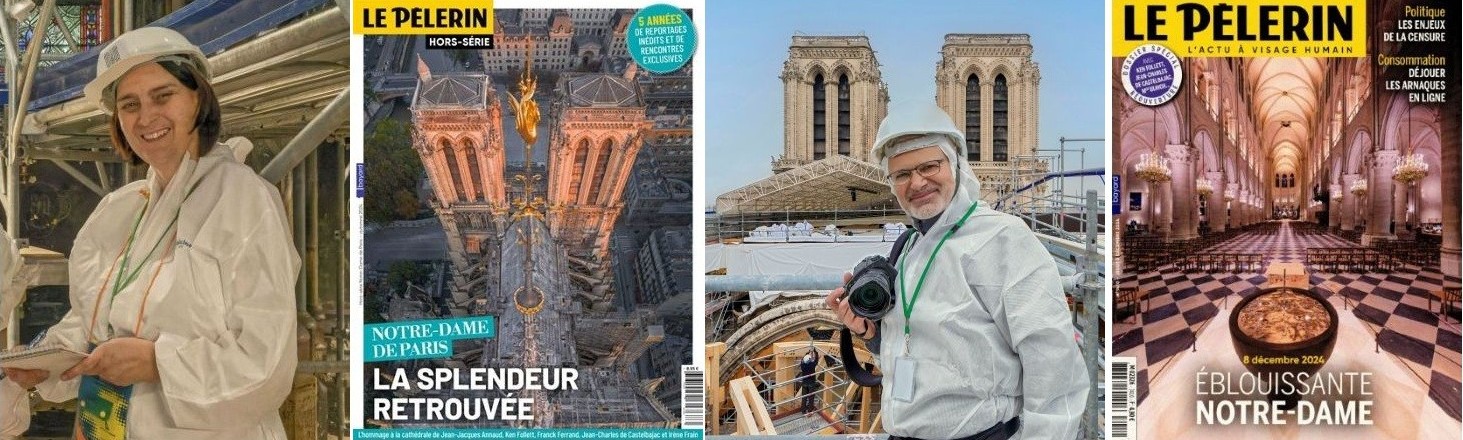

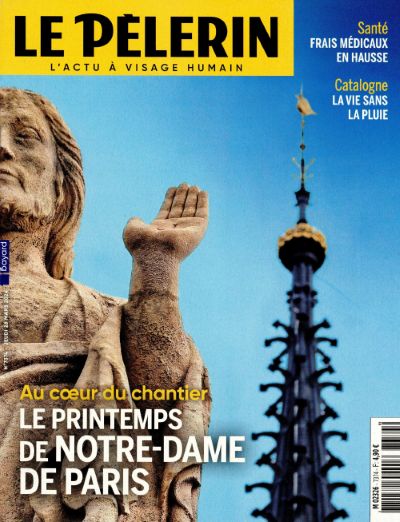

Few journalists were authorized to enter the worksite of Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral during the restoration period as often as Sophie Laurant, senior reporter for Le Pèlerin. And even fewer photographs were given as frequent and wide access to the site as Stéphane Compoint, an independent photojournalist. Here, Gary Lee Kraut interviews these two key witnesses to a dazzling restoration, illustrated with portraits, self-portraits and cover photos by Stéphane Compoint.

As we watched the flames rise and the spire fall on Notre-Dame Cathedral on April 15, 2019, those who lived in or had visited Paris before felt a nearly personal sense of loss. Notre-Dame was truly “our” Lady, whether beheld with the eyes of a Catholic or not. Even among the hundreds of millions who saw images of the conflagration but hadn’t yet had the pleasure of visiting the French capital, many spoke of the event as a calamity or a tragedy. Many would wallow in those feelings for days.

But for some, there was little time for heartache. The fire was a call to action—for firemen, the president and government officials (Notre-Dame belongs to the French state), Catholic Church officials, historical architects, scaffolders, logisticians, restoration specialists, foundation managers who would accept pledges and funds amounting to 840 million euros (940 million dollars at the time), lumberjacks, quarriers, etc., and journalists and photographers as well. I, myself, took a call from NBC Philadelphia the night of the fire. But once the (lead) dust had settled, media entrance to the cathedral was carefully limited.

Among those who repeatedly gained access to the wounded monument from 2020 to 2024, few journalists covered the restoration project as thoroughly as Sophie Laurant, senior history and cultural heritage reporter for Le Pèlerin, a weekly Christian general news magazine, France’s oldest continually published magazine (1873).

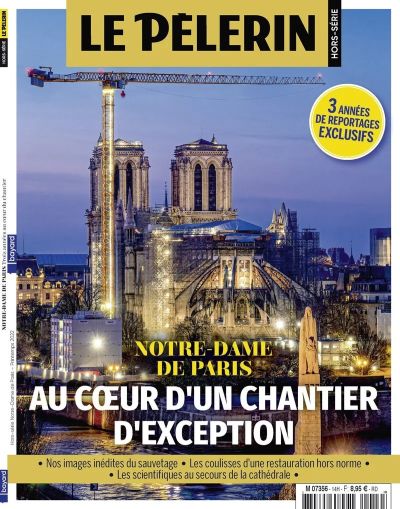

Even fewer, if any, photographers were authorized to enter the worksite as frequently and extensively as Stéphane Compoint, an independent photojournalist specialized in architecture, cultural heritage and aerial photography, and a World Press Photo winner, tasked with Le Pèlerin to cover the restoration project. Stéphane had earned his stripes as a photographer of Notre-Dame well before the fire; in 2013 he’d made major photographic study the cathedral for a special edition of Le Pèlerin, producing photographs that became precious historical documentation of the state of the cathedral before the fire. From the date of the fire until its reopening, he photographed Notre-Dame on 63 occasions from the inside and nearly as many times from outside.

Several days after the reopening of the cathedral to Catholic and non-Catholic visitors alike on December 8, I had the opportunity to interview Sophie and Stéphane, in writing. As you will read in the combined interview below, theirs is a precious testimony to the restoration process and to its technical achievements, its emotional impact, and the collective and individual investment involved, including their own.

(The original, French version of these interviews can be read here.)

Gary Lee Kraut: In your work you demonstrate an acute sensitivity toward heritage sights in general and religious heritage sights in particular. You’ve undoubtedly visited all of the Gothic cathedrals of France? But before examining these structures with the eyes of a professional journalist and photographer, what was your relationship with these magnificent mastodons of the Middle Ages? Do you recall the first time that you visited Notre-Dame?

Stéphane Compoint: A Parisian forever, I grew up in the 6th arrondissement. My grade school and high school were near Notre-Dame. The cathedral has always been a part of my immediate landscape.

My family was rather secular, even anticlerical. But my maternal grandfather drew closer to the God of the Catholic religion after the tragic death of his oldest son (my uncle), who died from drowning while trying to save a friend, who survived. He therefore became a believer and started going regularly to mass, often taking me with him to churches in the neighborhood (Saint Germain des Près, Saint Sulpice, Saint Séverin, Notre-Dame des Champs, Saint Germain l’Auxerrois, along with Notre-Dame) ever since I was a child. At the very least that taught me to be patient because at six years old mass can seem long. If I was well-behaved, I’d get a box of Legos afterwards!

Sophie Laurant: I grew up in Bourges, a lovely medieval town located in the very center of France. The town has one of France’s most beautiful Gothic cathedrals, built starting in 1195. It rose slightly after Notre-Dame (whose construction was launched in 1163) and is a contemporary of Chartres. Furthermore, my father was a history professor and often gave tours of the monument, of which the inhabitants are quite proud, whenever friends or family were visiting. So I learned at a young age how to distinguish Gothic art from Romanesque art. My father explained to us that Bourges was famous for the red of its stained-glass windows whereas it’s the blue of Chartres that dazzled. He pointed out that our cathedral, unlike most, didn’t have a transept but the shape of the overturned hull of a boat.

I don’t recall the first time that I visited Notre-Dame de Paris. It was undoubtedly with my parents when we went up to Paris as tourists. However, I do remember that when I was a university student [in Paris] I went in one Sunday afternoon when I was feeling quite lonely in the capital. By chance I arrived just when the traditional weekly organ concert was going on. It was magnificent. I went back several times afterward, especially since it was free, which is a blessing for a student.

Gary Lee Kraut: Where were you on Monday April 15, 2019 when you learned that Notre-Dame was in flames. How did your evening unfold?

Stéphane Compoint: I was at home, heaving with sobs! But I quickly got into a long phone conversation with Catherine Lalanne, the editor-in-chief of Le Pèlerin, which projected us both into the immediate future and into action, which did me a world of good. Because it was Monday, the day the weeklies go to press, we had to put in place an appropriate editorial strategy right away, modify the issue due to come out on the following Thursday, and launch a special edition that would be published the following Friday. We didn’t get many hours of sleep that week, but at least we were working rather than sitting passively faced with the enormous loss.

Sophie Laurant: While I was in the metro on my way home from work, I received a text from a colleague, but I didn’t realize how serious it was—not until I reached the foot of my building and got a call from my editor, Catherine Lalanne. She’d just asked that the deadline for our weekly edition going to press be pushed back since it was on its way to the printing press, as every Monday evening. She just had time to insert a large photo and a caption. I then followed the events on TV, while at the same time speaking with a friend who does restorations of historical monuments who explained to me that the outbreak of a fire is the nightmare of companies that restore roofing frameworks. I didn’t turn off the TV until it was clear that the monument had been saved. And the next morning I intentionally took a bus to work that passes by the cathedral. I had to see with my own eyes that it was still there. I even took a picture through the bus window to reassure myself. As soon as I arrived at work, we decided to republish our special edition that we’d brought out in 2013 for the cathedral’s 850th anniversary, adding in updated information. For each copy sold, 1€ was donated to the Notre-Dame fund. We sold 33,000 copies and therefore, from the start, had the feeling that we were being useful. It was important to overcome the disaster. Moreover, the architects [responsible for restoring Notre-Dame] asked to consult Stéphane’s photographs, which at that point had become historical documents.

Gary Lee Kraut: When were able to enter Notre-Dame for the first time following the fire? Tell us how that unfolded and about your impressions.

Stéphane Compoint: Despite its status as a Christian weekly, the negotiations between Le Pèlerin and the state’s media communications directors for the restauration project to allow me to enter the site were difficult. Finally, our salvation came from General Georgelin* himself, the person overseeing the cathedral’s restoration, a believer who was sensitive to the mid-elevation photographic work that I’d done with a tethered balloon in 2013 for the 850th anniversary of the cathedral. We gave him large prints of these photographs and he decorated his office with them. I was able to enter the wounded cathedral for the first time on March 3, 2020, ten and a half months after the fire.

Sophie Laurant: I finally went inside Notre-Dame on October 21, 2020. During the first year [after the fire] the teams were busy with decontaminating the lead and consolidating the cathedral. Also, under the management of General Georgelin, a very strict, top-down administration was put in place to filter press requests. Luckly, Le Pèlerin had published in 2013 a special edition magazine entirely devoted to Notre-Dame, prepared with assistance from the clergy. Stéphane was able to enter for an initial post-fire photo reportage in March 2020. Catherine than insisted—incessantly—to the general and to the communications services for the restoration project that Le Pèlerin wanted a print journalist to be able to enter. They finally accepted for us to become “partners,” allowing us to regularly follow the rehabilitation in pictures and in text. I didn’t go often, but more than most other media.

I have an indelible memory from that first visit of climbing scaffolding, of the incredible view over Paris that then revealed itself. When I reached the top of the walls of the cathedral, I had a view of the charred beams that were still stuck into the angles of the crossing of the transept. That’s all that remained of the base of the spire! It was then that I fully realized the extend of the task that lay ahead.

* GLK note: Notre-Dame Cathedral belongs to the French state and so it is the state’s responsibility to maintain the edifice. The day following the fire, President Emmanuel Macron announced his wish that the reconstruction be complete within five years. General Jean-Louis Georgelin was appointed to spearhead the project the next day. General Georgelin did not live to see it reopened since he died in a hiking accident on August 18, 2023.

Gary Lee Kraut: Carrying out the research necessary for the restoration project gave specialists the opportunity to deepen their knowledge of the building and its history. Were there any discoveries or analyses that particularly surprised or impressed you?

Sophie Laurant: Yes, the researchers were the first to mobilize, immediately after the fire. At the Association des Journalistes du Patrimoine*, we quickly organized press encounters with some of them. Their primary message was the following: “We have a lot of information about Notre-Dame and we have to put it to the service of the restoration.” Immediately, the architects** asked them to take sample, to carry out analyses and studies, to make surveys and collect data throughout the monument in order to document as much as possible all of the elements, including the debris. These details studies enabled them to refine their restoration strategy. For example, to select a limestone very similar to the origin when cutting new stones.

Over those five years, the specialists discovered enormous amounts of information about Notre-Dame. For example, that the walls were consolidated by enormous iron staples. We didn’t think that that technique had been so used in the 12th century.

But the most spectacular discovery is undoubtedly the uncovering during the archeological digs at the crossing of the transept of high-quality pieces of sculptures from the medieval jube [also known as a rood or choir screen in English]. That decorative wall enclosed the church’s chancel, separating the sacred space where mass was said from the more secular space of the nave where the public came to hear (but not see) the service. Catholic liturgy evolved in the 16th century, prompted by the Protestant Reform movement. Jubes were destroyed in almost all churches and cathedrals in order to bring the clergy and the congregation closer together and allow a better understanding the ceremonial rites. However, since the sculpted figures represented Christ, Mary, the Apostles, etc., the workers had the habit of piously burying their pieces on site as they removed them. That’s why archeologists have found pieces of the jube in many cathedrals, such as in Bourges or Chartres. What’s incredible here at Notre-Dame is that sculptures retained colors that would have been lost if they’d stayed in contact with the air inside the building. On certain figures from the Gospels, we see that they have blue eyes or a delicately pink complexion, as in illuminated manuscript from the period. It’s magnificent! They’re now exhibited at the Cluny Museum of the Middle Ages in Paris. I also learned that one of the heads found during prior work on the cathedral in the 19th century, and that’s now found at Duke University in North Carolina, fits perfectly with a bust that was found in March 2022. For a project called “Notre-Dame in color,” the American researcher Jennifer Feltman is pursuing research with French colleagues to gather together the different pieces.

Stéphane Compoint: As a photo-journalist I’ve participated in many campaigns of archeological excavations throughout the world (Egypt, Turkey, Peru, Chili, etc.), including underwater excavations of the Lighthouse of Alexandria from 1995 to 1997, for which I won a World Press Photo. I was particularly moved by the discovery of the medieval jube in the spring of 2022. Seeing the face of Christ, eyes closed, emerging from the archeologists’ large and small brushes in the middle of the crossing of the transept is something that I’ll never forget. I also remember the reaction of the chief archeologist, who was right next to me at that moment: “The greatest emotion of my career!” Since I was the only press photographer on site that day, it gave me even greater professional satisfaction.

* GLK note: The Association des Journalistes du Patrimoine is France’s association of journalists covering all manner of cultural heritage. From 2016 to 2022, Sophie Laurant served as its president. Gary Lee Kraut served as the association’s secretary general 2016-2020. Stéphane Compoint is also a member.

** GLK note: In France, historical monuments are preserved by specialized architects known as “Architectes des Bâtiments de France.” These civil servants entrust restoration projects to other specialists, the “architectes en chef des Monuments historiques.” Philippe Villeneuve is the chief architect in charge of the cathedral restoration project.

Gary Lee Kraut: Over the course of your respective work, you’ve met many craftsmen, workers and managers of the restoration project, in Paris and throughout France. Are there any whose approach or personality particularly impressed or fascinated you?

Sophie Laurant: They were all high-level, passionate craftsmen. I especially appreciated meeting the painting restorer Marie Parant, who coordinated one of the groups that restored the paintings in the chapels of the choir of Notre-Dame. A great admirer of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc*, the architect who painted them in the 19th century, she invited me to visit her workshop near Bastille to show me documents and help me understand the quality of the colors. She also participated in the “chorale des compagnons,” a chorus consisting of all those who took part in the restoration, whether archeologists, logistic specialists, stone cutters, etc. The chorus sang inside the cathedral on Dec. 11, [several days after its reopening,] to celebrate the working community that they formed together. We could sense a real “Notre-Dame effect” that had unified them, a mix of pride with respect to the monument, of the joy of working on a common project, and a fervor for something greater than themselves individually.

I was also struck by the strong personality of Loïc Desmonts, a young lead carpenter (only 25 years old!), who’s redeveloping in Normandy the art of building wooden framework using medieval methods. He and his team cut wood while it’s still green using hand tools. He also promotes the “French-style scribing tradition in timber framing,” which is a way of creating on the ground a full-scale drawing of each piece of the frame before cutting it. That tradition of scribing has existed since the 13th century and is recognized by UNESCO on its list of “intangible cultural heritage of humanity.” While visiting him, I met members of the NGO “Carpenters Without Borders.” Among them were two American craftsmen who spoke to me with tears in their eyes of their love for Notre-Dame, the reason that they came to France to give a hand to their French colleagues. There are in fact very few carpenters anywhere in the world with the know-how to cut the framework in the way it was done back in the day.

Finally, there’s Iris Serrières, a stained-glass artist who works in the company run by her mother, the stained-glass restorer and creator Flavie Vincent-Petit, in Troyes [100 miles southeast of Paris]. When I met this deliberate and joyful young woman, she was hesitating between becoming a theologian and a master glassmaking! Maybe, she said, she could do both. The family workshop restored a portion of the cathedral’s 24 upper bay windows. The two women shared with me their feeling about being a part of a long line of master-glassmakers and of rediscovering how and continuing “to combine intelligence, gesture and spirituality” so that “these windows were again legible.”

Stéphane Compoint: I was impressed by the encyclopedic knowledge that Philippe Villeneuve, the chief architect, has of the monument and by the sound way in which he made decisions that were crucial but far from obvious in the days following the fire. I also appreciated the personality of the head scaffolder, Didier Cuiset, whose academic training is limited but whose know-how is exceptional. Like many journeymen, he comes from a modest background and was brought up with little inclination to speak of oneself, but he had to learn how to explain what he knows and how he knows it in order to satisfy the media. He made a lot of progress in five years.

*GLK note: Viollet-le-Duc led a major restoration of Notre-Dame in the middle of the 19th century. In doing so, he also added new elements, some of which existed but in different forms over the centuries, including the spire that collapsed during the fire and has since been rebuilt.

Gary Lee Kraut: Was there a moment during your journalistic or photographic work inside the cathedral that particularly surprised you or that has left a lasting impression?

Sophie Laurant: There was one moment that I’ll remember for a long time. It was in the spring of 2022 when I decided to interview the crane operator who was piloting the crane from 80 meters (262 feet) overhead. The crane was there throughout the entire project. In order to reach him, I had to take an elevator up to a tiny platform, 60 meters (197 feet) up, and from there climb a caged ladder the final 20 meters (65 feet) before reaching his heated and comfortable cabin. I had vertigo from the start, and I was afraid of stopping paralyzed in the middle of the ladder, suspended in mid-air. I decided that I’d rather give up on attempting the final ascent, because if ever I blocked ongoing work due to a panic attack, I undoubtedly would never be given permission onto the site again. The crane operator, very much at ease up there, offered instead to conduct the interview on the tiny platform! I wasn’t so calm there either, but I didn’t dare refuse. So in the cold and the wind, with the crane lightly swaying, I gathered my courage, avoided look down at the miniscule workers working down below on the temporary roof of Notre-Dame, and I asked him my questions. I’m rather proud to have succeeded because at home I have vertigo on a stool!

Stéphane Compoint: In the summer of 2020, at the end of a day photographing inside the cathedral, at one-thirty in the morning, I was struck by an unexpected encounter with the top of the charred spire imbedded in the exterior curve of an arch of the nave. I’d entered the building at 7:30 a.m. and hadn’t eaten or drunk for 18 hours, but that vision, that photo, was well worth the effort! In the fall of 2020, I also had that first long-awaited overall exterior view that took in all of the devastated wood framing, which I was able to take thanks for a giant tripod (of my own creation) that I’d raised about 15 meters (49 feet) above the devastated transept crossing.

Gary Lee Kraut: Do you feel that the public was sufficiently informed throughout the rehabilitation period? Did you encounter any difficulties doing your journalistic work?

Sophie Laurant: In the end a lot of articles were written. The entire international press covered the project, from near and from far. It’s true that the public powers overseeing the project were selective in choosing media that could enter the site and they limited access. Some of the reasons are understandable. The cathedral was entirely covered in lead dust. We had to get entirely undressed in a special chamber, put on a disposable boilersuit, and take a shower and shampoo when we finally left, like all workers who enter a “contaminated zone.” Furthermore, the project had to be done in five years, so the teams didn’t have much time to devote to the press. Clearly, it was difficult for the journalists to endure, to have to incessantly request authorization to interview anyone involved in the project. But at Le Pèlerin we had the privilege of being able to follow operations on a regular basis. I entered the cathedral seven times over five years. Stéphane entered far more frequently.

Gary Lee Kraut: Sophie, you wrote most of the text and, Stéphane, you took the photographs for the special edition of Le Pèlerin about the “exceptional construction site” of Notre-Dame published to coincide with the reopening of the cathedral. Does this signal the end of the Notre-Dame adventure for you or will you continue to report on and photograph Notre-Dame?

Stéphane Compoint: After the reopening, Le Pèlerin will naturally reduce its written and photographic coverage of the construction site. Nevertheless, work will continue for about another three years on the exterior of the cathedral, particularly around the apse and the buttresses of the nave and the chancel. We’ll try to be present at key moments during that work.

Sophie Laurant: We’re going to continue to follow the restoration which is now focused on the chevet [east end] and gables of the cathedral, outside. Stéphane will also try to exhaustively document the cathedral as it today, as he did in 2013. And we’re going to be very attentive to the choice of master glassmaker who will be designing new windows for the southern side of the nave; the installation of contemporary tapestries in the northern chapel in the next 18 months; the upcoming creation of a museum decided to Notre-Dame in the Hôtel-Dieu [the old hospital that occupies one side of the square in front of cathedral], and the square itself that will be entirely remodeled and modernize so as to allow for a better reception and flow for visitors. We’ll likely be publishing many of these reports on our internet site over the coming years.

Gary Lee Kraut: Having followed the restoration these past five years, has your view of the cathedral changed?

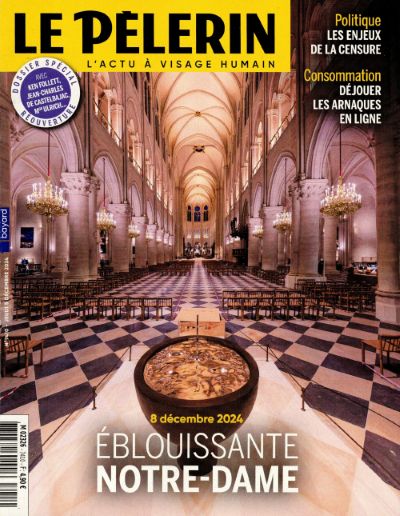

Sophie Laurant: Yes. I now know it very well, whereas before it was just one of many cathedrals that I didn’t enter very often before the fire. And I remember its grey walls, the semi-darkness, the crowds. Now it’s blond, clean, extremely well lit, and that showcases the paintings (now all cleaned) unlike in any other church in France.

Stéphane Compoint: The first thing that changed in my view of the cathedral was that I was better able to measure the extent to which the work of the builders of the 12th and 13th centuries is full of technical achievements. Being able to listen to lead architects speaking often and at length on site is worth any number of lectures in a lecture hall. I therefore learned a lot of fascinating things about a field—architecture—that has always interested me (my father was an architect). And the way I see Notre-Dame has changed because we’ve gone from a dark cathedral to a luminous cathedral, and, like many photographers, I like the light! Finally, I know that from now on I’ll see images of the expert craftsmen and journeymen at work superimposed onto my actual view whenever I visit the restored cathedral, and that’s a privilege.

To learn more about Sophie Laurant’s journalistic work, see here.

To learn more about Stéphane Compoint’s photographic work, see here.

Entrance to Notre-Dame Cathedral is free. Timed reservations are not required but can help avoid long lines, especially during busy periods. For a timed reservation, see here.

© 2024 Gary Lee Kraut / France Revisited

What a marvelous account, Gary. It let me revisit Notre-Dame while learning new details about its history and contents. Merci beaucoup!

The Notre-Dame fire was truly a heartbreaking moment that resonated across the world. It’s remarkable how, even amid the sorrow, so many individuals and groups immediately mobilized to restore such a historic treasure. Your reflection captures both the emotional weight of the tragedy and the incredible collective effort that followed. It’s a powerful reminder of how cultural landmarks hold deep meaning and inspire action beyond borders and beliefs.