A stretch of beach and distant pier in the Malo-les-Bains district of Dunkirk, a portion of the site of the evacuation of 1940. Photo GLK.

My parents were both great readers. In the family room, my father had built wall-to-ceiling shelves that my parents then filled with books. These were mostly adult books, poetry for my mother, fiction for my father. As I grew up, I came to enjoy his favorite authors: Mark Twain, with “Tom Sawyer” and “Huckleberry Finn,” of course, but also the less well known “Life on the Mississippi,” “Innocents Abroad,” and “Puddn’head Wilson,” a detective story.

They passed their love of reading on to me. I had my own large Philippine mahogany bookcase in my bedroom. It held, among others, the Oz stories, but I was a purist. I had only the original ones, those written by L. Frank Baum himself. The Oz books written by a successor after he died were just not the same. I also had a large collection of fairy tale books, notably the “color” series by Andrew Lang.

My father, an engineer working for a large oil company, was often gone on business, especially during World War II, which America joined after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, when I was six years old. My father did not fight in the war as a soldier. He was an engineer, and the military draft authorities considered him more important in that role. Still, Papa would be away for weeks at a time, in the Pacific Northwest and Canada where there were oil deposits. He would send me postcards, including a humorous one showing a giant mosquito carrying off a deer. They were fun, but it wasn’t the same as having him there, reading me grownup stories like “The Count of Monte Cristo” instead of just the Mother Westwind stories Mama read to me about animals named Jimmy Skunk, Jerry Muskrat and Joe Otter.

I was bored staying home with Mama alone while my father was away. Luckily, I was saved by the neighbors. My father was often transferred because of his work, so we rented a lot of the time rather than buy a home. In 1942, we moved to Hillsborough, California. The Hammonds, our landlords, lived next door. They were not demanding or oppressive, the way landlords are often portrayed. They were open and friendly. Mrs. Hammond was particularly kind to me. One day she gave me a great gift in the form of an invitation. “I know how much you love our old house,” she said to me. “Our doors are never locked, you can come in whenever you want.” This was an unusual invitation, but for me, Mrs. Hammond was an unusual person because so unlike Mama. Her dress style was a great contrast to Mama’s. Instead of straight skirts and crisply ironed white blouses topped by cardigan sweaters, Mrs. Hammond’s home attire was faded blue jeans. They were perfect for the gardening she loved. During the war the Hammonds had a vegetable garden, a “Victory Garden” as they were called, the idea being that by growing a part of our own food, we were helping the war effort. I followed their example, and was proud of the carrots, beets, peas and string beans that I eventually provided for our dinner table.

I took advantage of Mrs. Hammond’s offer to visit next door whenever I wanted and I’d wander around the house, a big Victorian that had been in the family for generations. I mostly stayed in the downstairs rooms, which had the most character, where I would soak up the atmosphere of warmth and kindness I felt there. Especially, I’d visit her daughters Kate and Jane. Kate was six months older than I, and Jane, six months younger. They were my best friends. We played together almost every day, always at their house. Sometimes we went up to the attic, which had a trunk full of old clothes we could dress up in.

The Hammonds had only one bookcase, kept in what they called “the music room” because there was an upright piano against one wall. There, I often joined Kate and Jane to practice our scales. Music lessons were a must for nice upper middle-class girls like the three of us, the piano being the most popular instrument.

One day, when it was not my turn on the piano, I drifted over to the bookshelf across the room and explored its small collection. There were mostly medical textbooks left over from Mrs. Hammond’s time as a nurse before her marriage. But I also discovered a slim volume called “The Snow Goose” by the American writer Paul Gallico. It is a tale deriving from a real event of the Second World War, prior to the entry of the United States. It recounts the desperate sea evacuation of mostly British along with French soldiers trapped on the beaches at Dunkirk in northern France in 1940, using many small non-military ships and craft along with British destroyers and other military vessels. In the story, a large Canada goose plays a role in the rescue. “If you saw the goose,” one of the story’s fictional survivors says, “you were eventually saved.”

I read “The Snow Goose” for the first time right there on the floor in the Hammonds’ music room. It is a beautiful story, about a hunchbacked painter, an orphan girl, and a Canada goose, but because the painter dies during the evacuation it is very sad. It made me weep. Kate and Jane, busy working on a duet at the piano, did not notice my tears.

I continued to find “The Snow Goose” compelling. Seated on the floor in the Hammonds’ music room, I read it over and over. I kept rereading it until my father was transferred to Texas in 1948 and we moved away, when I was 13. Before we moved, I thought, briefly, of stealing “The Snow Goose”, carrying it off with me, but I could not do such a thing to the Hammonds, who had been such good friends to me. I left it where it was.

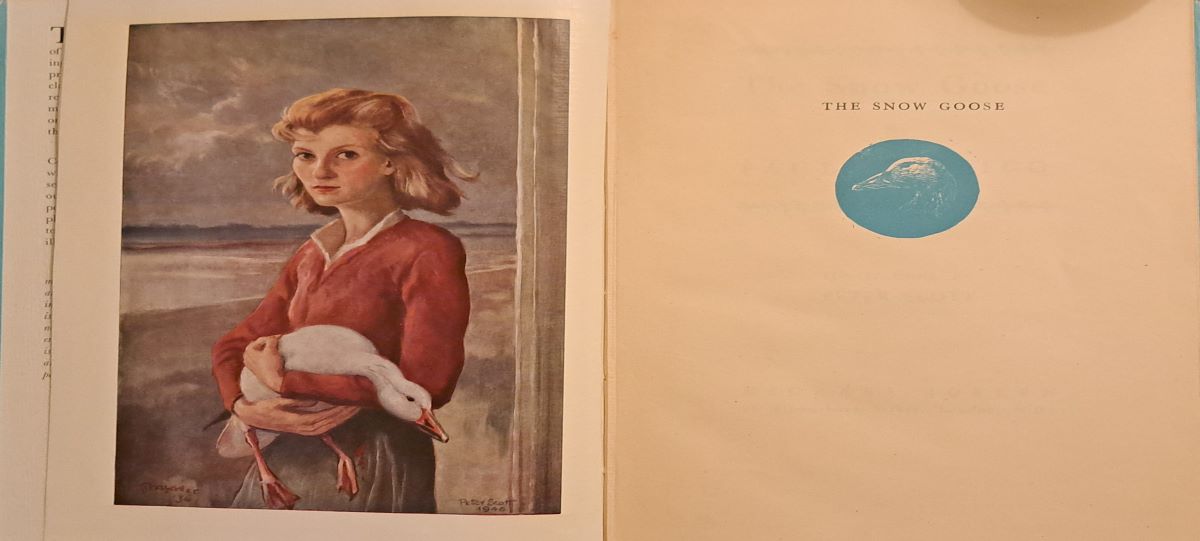

Years passed before I saw another copy of “The Snow Goose.” I came across it in a used bookstore in Montreal, when my late husband Earl and I were on vacation in Canada. This lovely book would be all mine, forever. It is a nicer copy than the one the Hammonds had, a special edition with four full-page color illustrations: one of the orphan girl with the goose in her arms, two of geese flying over the old lighthouse where the painter lived, and one of the Snow Goose alone in flight.

In my home in Paris where I now live, I have a bookshelf holding books that have special meaning for me. Occasionally, I’ll pick one up just to hold it in my hands or to flip through its pages or to reread it. Recently, for no conscious reason, I found myself drawn to my old and beautiful copy of the “The Snow Goose.” I reread it that afternoon and I loved it just as much as ever. I felt a connection with my six-year-old self sitting on the floor in the Hammonds’ music room. Though I hadn’t picked it up in many years, I realized that the book had been a part of my life for more than 80 years. Yet in the decades that I’ve lived in Paris, I had never been to Dunkirk, even though it’s only about 180 miles northwest of the city. I felt a sudden desire—no, a need—to go there.

I made plans to go on my own for one week this past September. I took the train to Dunkirk, a 2½-hour ride from Paris’s Gare du Nord. My daughter had reserved for me a nice hotel near the beach in Malo-les-Bains, once a distinct seaside resort, now fully a part of Dunkirk. It was from Malo that much of the beach evacuation took place in 1940.

My first day there produced typical Northern France weather, a sky like homogenous gray soup threatening rain, and a brisk wind. Reluctantly, I postponed my plan to stroll by the beach. I settled for visiting the nearby Dunkirk War Museum, Musée Dunkerque 1940 – Opération Dynamo. Operation Dynamo was the codename for the wartime evacuation. Visiting the informative museum was well worth my time. While many of the displays and photos naturally tell about the war, the evacuation and its aftermath, I was intrigued by two photos of Dunkirk and Malo before the war, before they were pounded into rubble by German bombings. In the few hours I’d been in Dunkirk, I could already see that most of what now stands has been built since the war. Always a book lover, I bought two books, one in French, one in English, both titled “Operation Dynamo.”

The following day the weather began to clear. I went for a walk on the paved promenade, what the locals call la digue (the dike), that runs the full length of the beach. I could see far out across the water, beyond the low dunes with gray-green marsh grass growing in the sand. This was one of the sites of the evacuation. There was still wind, but not so strong, and it didn’t buffet the numerous small white sailboats I saw. In a trick of the mind, I imagined that they were part of the flotilla of small craft arriving to carry the stranded soldiers away to safety to the larger ships waiting farther out, to take them on to safety in England.

The next day, I returned to the path along the beach, now with “The Snow Goose” in my purse. It wasn’t the beautiful copy I had at home, but a pocket-size edition that a friend whom I had told about this touching story and about my plan to visit Dunkirk had kindly sent me from England. I found a wooden bench where, under blue skies with powder puff white clouds, I sat and began to read. From time to time, I looked along the beaches around me where the men had awaited rescue and out to the sea before me. I noticed how shallow the water was for a good distance out. For the first time, I truly understood the need for small boats to evacuate the soldiers. The larger boats that had tried to come in to pick up the stranded soldiers could not, because there was not enough depth. Thus hindered, they made easy targets for the German planes overhead, diving and strafing. Still, the little boats were not spared.

I reread the “The Snow Goose” entirely that afternoon, occasionally pausing to contemplate my surroundings. In my mind’s eye I could see those little boats trying to dart away from the diving planes. Some got through. Others did not. The little boat in “The Snow Goose” was one of the latter. For the lonely painter and the orphan girl who had come to love him, there was only loss. Although I usually prefer happy endings, such an ending would never have touched me the way this sad one has. I was moved in an unusual way, not to tears for a beautiful tale, but by the realization of how very close this evacuation, a “non-victory” as Churchill put it, came to becoming a resounding defeat. Yet in the final accounting, 340,000 British and French troops were successfully evacuated. They formed the nucleus of an army which would fight again, and, four years later, with Americans now on their side, return to the shores of France to eventually defeat Germany.

Though this was my first time in Dunkirk, being there was like visiting my own past. I thought of the kindness of the Hammonds and our peaceable lives in California. I thought about the effects of World War II on the American home front, with our sense of a just and necessary war, and the effort to engage ordinary civilians, women and even children like me, through Victory Gardens and War Bond drives, events that marked my childhood and have stayed with me as “The Snow Goose” has for over 80 years. As I sat there, watching families now walking peacefully in the sunshine along the beach and looking out to the calm waters and little sailboats sliding on the sea, I realized that I am now old enough to remember a time that fewer and fewer do. I realized this not with sadness or even nostalgia, but with a sense of privilege at having been a part of those heroic times.

© 2024, Alice Evleth

Read the accompanying article Dunkirk 1940, Dunkirk Today: Advice for a Day Trip or an Overnight by Gary Lee Kraut.

How beautiful. Thank you Alice, for writing this, and thank you Gary for publishing it.

I think I need to go to Dunkirk also. Thank you for the inspiration, and the tips about how to do so.

What a lovely reminiscence this was! I have just read the Snow Goose, and after reading around the subject, discovered that the artist Sir Peter Markham Scott (an ornithologist and wildlife painter, among other things) illustrated the book, and apparently based his picture of the girl holding the goose on his wife at the time, famous novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard (author of wonderful war time literature like the Cazelets). Wonderful connections!