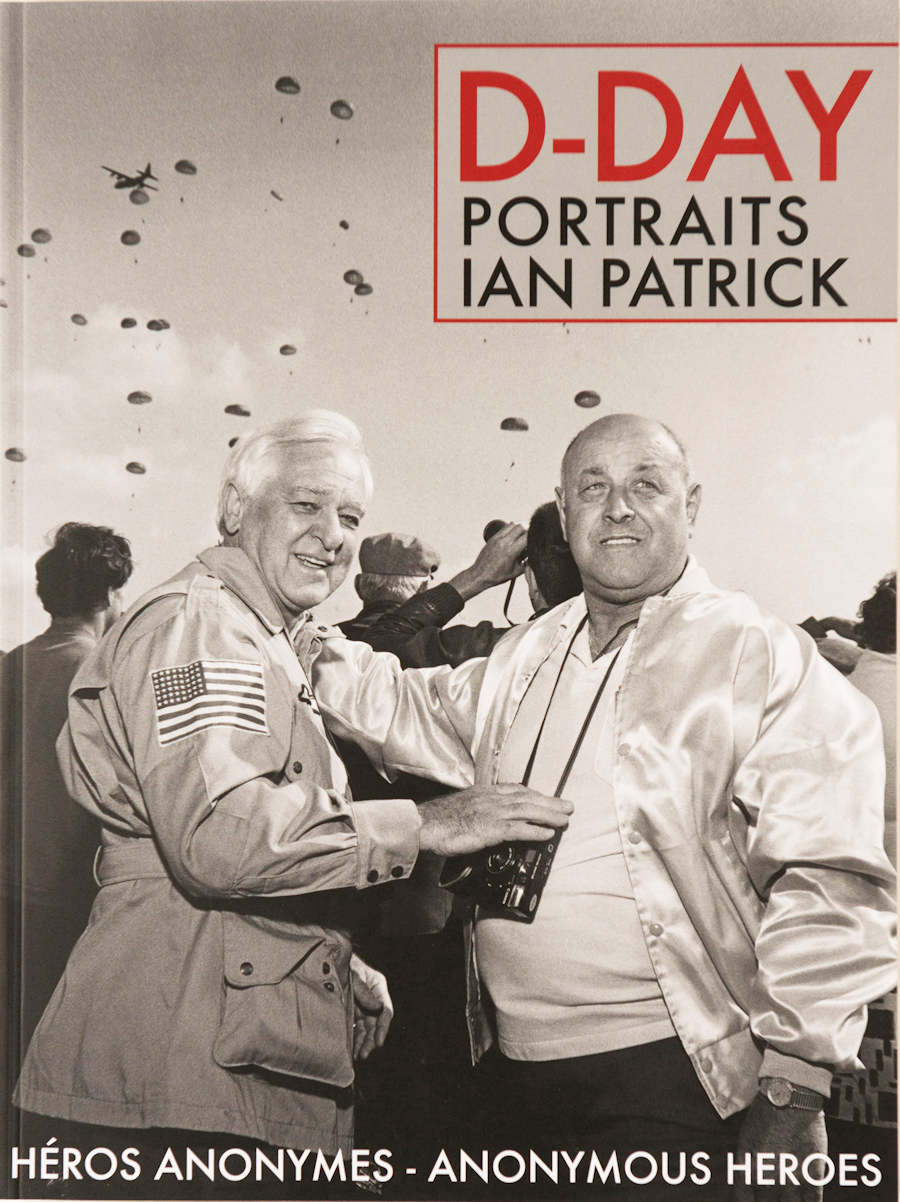

Photo above: Bob Murphy and Brank Bilich, veterans of the 82nd Airborne watching a parachute drop, 1993. Cover photo (cropped) of Ian Patrick’s D-Day Portraits: Héros Anonymes – Anonymous Heroes. © Ian Patrick.

On the triple occasion of the 80th anniversary of D-Day, an exhibition of Ian Patrick’s portraits of Normandy veterans at the Army Museum at the Invalides in Paris, and the publication of the expanded second edition of D-Day Portraits: Héros Anonymes – Anonymous Heroes, his collection of portraits and first-hand accounts of veterans of the Invasion of Normandy who have returned over the years, I sat down with Ian to discuss his relationship with Normandy, with WWII veterans, and with the veteran who first awakened his interest in the “anonymous heroes” of the invasion that changed the course of the war: his father.

Ian Patrick is an American-born photographer, now a dual citizen, who moved to Paris in 1979 after launching a successful career as a portraitist in New York, where he photographed such well-known cultural figures of the time as Bob Marley and Andy Warhol, among others. It wasn’t until Ian was living in France that his father, William Patrick, when visiting, told him that he had taken part in the Invasion of Normandy 1944. Together, in 1980, they visited Utah Beach, where his father had landed six days after D-Day. Since then, Ian has returned frequently to the D-Day Landing Zone to photograph veterans of the Invasion of Normandy. With the disappearance of the generation that fought in the Second World War, his 44-year project of photographing veterans is coming to an end.

What do you remember of the first time you visited the D-Day Landing Zone?

It was 1979. I’d done a photography job in La Rochelle, and since my assistant and I weren’t in a rush to get the car back to Paris, we drove up the Atlantic coast and cut across to Normandy. I remember seeing the sign for Omaha Beach and driving down to the beach and saying, “Well, there’s nothing here!” We drove up and down the beach a couple times, unimpressed, and then went up to the cemetery where we got the jaw-drop view of the tombs and the channel beyond the cliff. But we didn’t spend much time in the area because we had to get back to Paris.

Then the next time you went back was with your father?

Yes. In 1980. My father flew over on a military plane, which he could do for free as a career military man. He flew from California to Dover, Delaware, from Dover to the Azores, from the Azores to Ramstein, Germany. Then he took the train to Paris, Gare de l’Est, and walked over to our apartment by the canal [Saint-Martin]. Sometimes he’d just show up, without letting us know he was coming. But this time we knew he was coming because he wanted to meet Véronique, my fiancée at the time, before we got married.

After a few days in Paris, he was bored and he said, “How about taking me up to Normandy?” And I said, “Sure, Dad, but if it’s Calvados [apple brandy] you want we can get it in Paris.” And he said, “Yeh, I’d like some Calvados, too, but I’d like to visit Normandy because I was there in the war.” I said, “You never told me about that.” He said, “Well, let’s go up there and I’ll tell you all about it.”

At the time I had a “Quatrelle,” one of those funky little Renault cars, that wasn’t exactly a bomb on the road. Dad didn’t want to go on the freeway but on the smaller national roads because he figured he’d recognize all kinds of stuff. As soon as we got into Normandy, which you do fairly quickly from Paris, he started noticing signs for Calvados and he asked me why were there so many of them. I told him that there are lots of farmers who make and sell Calvados. He said, “Let’s go get some.” We were still two hours from the beach. We went into one, where I introduced my father and told the farmer that he wanted to try some Calvados. The farmer said, “Here’s 7 years, 10 years, 15 years.” My father said, “Let’s start with the 10 years.” He tasted it and he said, “My god, this is so much better than the stuff we had during the war. Get three bottles of that.” I said, “Three bottles, Dad?” He said, “Yeh, one for you, one for me, and one for right now.”

So we started drinking it at 9 o’clock in the morning and by the time we got to Utah Beach, we were feeling “in our cups,” as they used to say, and he started talking to me about his time in the war. He landed at Utah Beach on June 12, so the beach had been won by then, of course, but there were still corpses around. My father had started off the war as a pilot but blew his eardrums out, so they put him on the ground, which he was really disappointed about. He was an armorer, making sure that guns were perfectly in alignment and worked and the bombs properly place, anything to do with ammunition. They had a special place on the airstrip where they could lift the tail up and fire at targets to make sure that the guns were aligned correctly. What’s incredible is that they actually had gun cameras on those machine guns and rockets so that same evening the films were developed and they would project them in the barn of the farm where they were staying and write down what needed to be done. And they saw the carnage they were creating for the Germans.

When he arrived on the 12th, the airstrip where he was assigned, which was just behind Sainte Mère Eglise, was still being finished by the Corps of Engineers. It was being made so that their P47s wouldn’t have to go back to England to refuel and rearm. He was there until the end of August, after the Germans had been hammered in the Falaise Gap. From there he went to Le Mans, then Nancy, then Saint Dizier, and also provided support for the Battle of Hürtgen Forest and the Battle of the Bulge. They put special pouches under the wings to drop ammunition and supplies to the men who were stuck in the Hürtgen Forest. They then moved into Germany.

I knew practically nothing of this before going to Normandy with him. I knew that he was in the war but he never talked about it. He was a career army man but he never talked about the war. I lived on army bases as a kid and saw army stuff all the time. When you’re a little kid you play army but you don’t necessarily ask your father if he ever killed any Germans or stuff like that. It was with our trip to Normandy that he started talking about it.

Why do you think it took your father so long after the war to come to Normandy given that returning there came to mean so much to him?

My parents came to Paris in 1950 on their honeymoon from Austria, where my father was stationed. My mother was already pregnant with me. I have photographs of him in his uniform at the Eiffel Tower—in those days you had to wear your uniform when you traveled. They also went to Nice. After I was born, we lived in Austria and later we lived in Germany. We’d go on vacation to the French Riviera or the Italian Riviera. They liked going to Vienna as well. But Dad never talked about the war. After we moved to the U.S., they loved coming back to Europe because they lived a long time here. But Normandy wouldn’t have been a place that he would think of going with my mother. So when he came to visit alone that time, it was an opportunity for him to go and for me to go with him. My mother had no interest in the war. But when she came with him later, she realized the effort and the massiveness of the invasion and… you can’t help, even if you’re opposed to the military and to war, you can’t help but take your hat off to those people who were a part of it and who lived through it. My parents returned may times, especially my father.

That trip with your father, to whom you dedicate “Anonymous Heroes,” your book of veterans’ portraits and their first-hand accounts, must have been the spark to your interest in photographing veterans.

Yes. We drove up and down the Utah Beach that first time. He showed me certain bunkers where he would tell me what kind of shell had hit it to make the hole or the mark on it, using all this military jargon. He was into ammunition because that was his job. Then he wanted to find the farm where the airstrip had been. Of course, the strip was no longer there, and there was no sign marking where it had been. Also, most farmers in the area didn’t want visitors. But we drove into one farm in my “Quatrelle,” where we met a lady named Alice. It was lunchtime, and she and the family came out with their napkins in their hands. “Oui, Monsieur?” she said to me. “Excusez-nous,” I said, “Mon papa est vétéran…” and right away she said to him, “Entrez, monsieur.” So we went in and they brought out two plates and we sat down to eat with them. My father was in tears, he couldn’t believe it. Their welcome was so sweet. At the end of the meal, the farmer went out to the barn, or wherever he went, and he comes back with a half-full dirty old bottle of dark alcohol, and written in chalk on the bottle was “1944.” He gave us each a little snort of it. It was absolutely delicious and my father started crying again. He said, “This isn’t the kind of stuff that we had in 1944. What we had was green rotgut, whatever we could find that the Germans left behind.” From there we went into Sainte Mère Eglise and we meet other people who then invited us in for coffee. My father couldn’t believe the welcome we were receiving. I took some pictures of him on the beach and in different places.

After that I decided to go up there every year on the sixth of June, and I would take pictures. Many times, there were no veterans at all. I would go each year, whether my father would come to France or not. Years later, I went to a fair in a hotel in Paris promoting Normandy for the upcoming 50th anniversary [1994]. By that time I’d already done a number of photographs. I met the secretary of the Comité du Débarquement [Landing Committee] and showed her some pictures. She said, “Oh c’est bien!” Then she explained that not only was she a part of the Landing Committee but she was also the director of the Musée de la Tapisserie in Bayeux, and she invited me to show my work in the Salle du Chevalier, which is the vaulted hall that later became the giftshop of the museum. So that was the first exhibition of my Normandy work, which I’d been taking just out of my own interest until then. From then on, she would send me an official invitation to the June 6th ceremonies every year so that I had actual credentials to go wherever I wanted to photograph veterans.

I also then started to interview the veterans, usually calling them on the phone after meeting them since there was no time to interview them during the ceremonies. On the phone, they would speak differently, more freely, as though to themselves, since they were alone and weren’t perturbed by my presence. Sometimes they’d go off track and I’d bring them back with another question. I asked them to tell me about their experience, whatever was bizarre or sad or happy that they wanted to recall. Most of them didn’t talk about terrible stuff. Some of the ones who landed on Omaha Beach did, in a very cold manner. A lot of them didn’t want to talk at all. I just tried to let them tell me what they wanted to tell me.

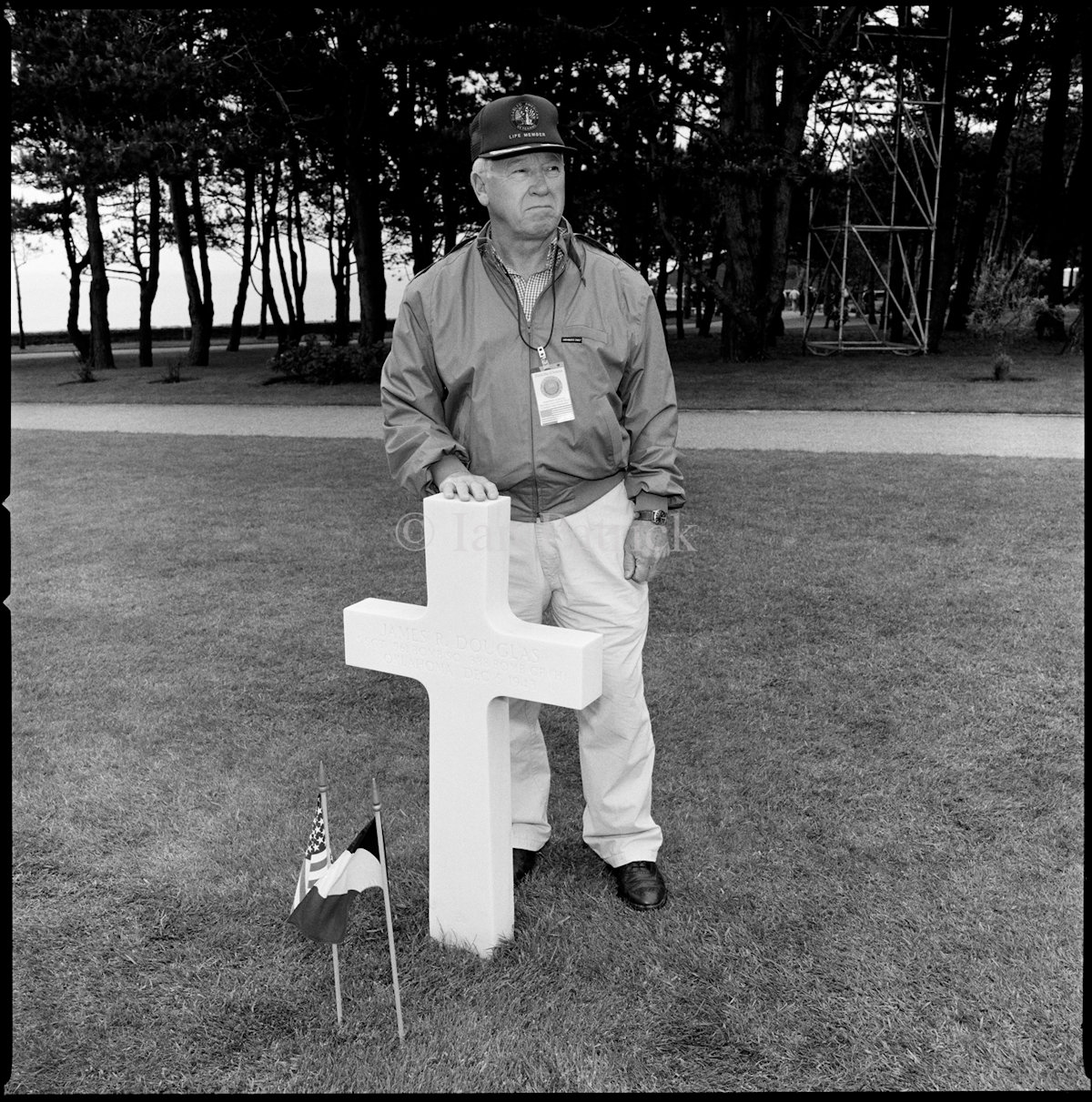

I wasn’t necessarily meeting them at the ceremonies. I would attend the big ceremonies, and I might come upon a smaller one here and there that I only learned about when I got there. Nine times out of ten it was just serendipity that brought me in contact with a veteran. I have photographed veterans I happened to come upon in the cemeteries while they’re paying homage to a particular person. I got the shot of Major Howard at Pegasus Bridge because the owner of the B&B where we were staying during the anniversary that year [1993] told us about an event that was taking place there on June 5th. So we immediately went there, and there they were, Major Howard and a few men popping Champagne. There weren’t that many people. There were no guys dressed up as paratroopers as you’d see more recently. There was just Madame Gondrée at the café by the bridge when I was in there talking with Bill Millin. Some years when there were few veterans, I would do landscapes, which is why there are some landscapes in the show and in the book, photographs of ceremonies and of places that reek with history.

In my first show for the 50th anniversary there was very little text next to the portraits. Just who they are, were they are, basic facts. Then little by little, as I took more portraits and gathered more stories, I realized that I had material for a book, which I put together with the backing of the Military Museum at the Invalides [in Paris] for the 65th anniversary in 2009. That year I also had exhibitions of my work at the Invalides and at the Museum of the Battle of Normandy in Bayeux, near the British Cemetery. That’s the first time that I put together the photos with the text [first-hand accounts] at an exhibition as well as putting them in the book.

After that first edition I continued to meet veterans, and even since completing the new edition last year I’ve met others. For example, I recently met some Belgian soldiers who managed to get to England during the war and joined up with a brigade that took part in the Invasion of Normandy under British command.

How often did your father return after that first visit?

He would come every two or every five years. He would come for the big ceremonies and some little ones as well. Even if it wasn’t the sixth of June, whenever my parents would come to France they would usually drive to Normandy, even without me.

In the early years of his visits, my father and I would be at Sainte Mère Eglise and school children would come up to him and ask him for his autograph. My father said, “Why do they want an autograph from me? I’m just an old veteran.” I had to bug him to put on his medals. He didn’t want to wear them, it embarrassed him because he thought it would be showing off. He didn’t even bring them for the 65th [2009] though I thought he might. I hadn’t told him in advance, but he was going to get the Legion of Honor at the Invalides that year along with 50 other veterans. I didn’t want to tell him before he got to France because I knew that he would be angry about getting a medal now. Finally, I told him about it when he got to France. He was kind of embarrassed. He hadn’t brought his medals, so I called my sister and asked her to dig through the drawers in his bedroom to find them and to send them asap. She did, and the day of the ceremony I pinned them on him. He complained, “Where the hell did you get those?” But he was enthralled by the whole thing, a big ceremony—he thought it was incredible. Then we all went to Normandy for the 65th anniversary commemorations. They reserved a train for the veterans, red carpet at the station, the band of the Garde Républicaine playing Glen Miller, wine and foie gras on the train. Then a bus took us from Caen to the American Cemetery. My father sat with all of the veterans on the podium, where they all shook Obama’s hand and Sarkozy’s hand. Then we all went back to Paris, exhausted.

He and my mother both passed away a year later, in 2010. They wanted their ashes spread together at Utah Beach, which we did.

Why did you want to put together a new edition of your book?

Because this could be the der des ders, the last flame. There are at least 25 additional veterans in this edition. I’ve met a lot more British and Americans but especially British through British families who live or have vacation homes in Normandy. I’ve gotten to know a lot of people in Normandy over the years. The British and the Dutch get together a lot, say for a drink on a Thursday or Friday evening, and a lot of them have fathers who were veterans. So I’d meet the fathers when they came over. Many of them have become part of the Deep Respect Association, with which I’m involved. [Editor’s note: Created in 2010, Deep Respect is a Normandy-based non-profit whose mission is to preserve and transmit the memory of veterans of the Second World War who contributed to the success of Operation Overload and to help veterans who participated in the Battle of Normandy visit the region.] We take around the veterans when they visit and it’s super interesting listening to them talk about their battles.

A series of your portraits and stories from the book are now on permanent display at the Overlord Museum Ohama Beach that’s located at the round-about where one turns to enter the Normandy American Cemetery. How did that come about?

The museum houses a tremendous collection of war materials—tanks, artillery, much more—started in the 1970s by Michel Leloup. He presented some of it in a museum in Falaise but as he grew the collection he began looking for more space and for a location with potential to draw a wider audience. He died before the project to move it to the site near the American Cemetery was completed. It was opened in 2013 by his son Nicolas.

For the 70th anniversary, in 2014, I had an exhibition at the round-about at Omaha Beach where the big monuments are located. Nicolas saw the exhibition and asked if he could buy some of the photos. I said, “Sure.” He bought about five. Since the veterans in the some of the photographs were at the event, we got pictures of them with the photographs, which they signed, which helped promote the museum. Over the next few years, the museum really took off, so Nicolas decided to expand the museum to show more of the collection, and in part of it he’s now consecrated one long corridor to presenting about 70 of my photographs—a lot of which he bought and some of which I donated—along with the text of the stories the veterans told me. My daughter Leah did the scenography and the soundtrack of 40s music and various sounds (waves, planes, bombs) for the exhibition.

You’ve now been photographing veterans for 44 years. With so few Normandy veterans still with us, and very few able or willing to travel, where does your project go from here?

I’ll still see some veterans this year and possibly next. But since I am basically a portraitist, there will soon no longer be men to photograph. That means that the project is now passing into the archival stage. It’s important to show them. I want to help maintain through the show at the Invalides, the permanent exhibition at the museum and the book the memory of those who are or will soon no longer be around to share their stories first-hand. The portraits are a way of people getting to know these veterans as they were as young men and as they were when I met them.

Where to see Ian Patrick’s photographic work

– His personal website Ian Patrick Photographer.

– Permanent exhibition at the Overlord Museum, near the entrance to the Normandy American Cemetery, Colleville-sur-Mer.

– The book: Héros Anonymes – Anonymous Heroes: D-Day Portraits. The captions and first-hand accounts of veterans are in both English and French. The book is available at major museums in the Normandy Landing Zone—the Overlord Museum, the Airborne Museum in Sainte Mère Eglise, the Arromanches Museum, the Utah Beach Museum and the Pegasus Bridge Museum—as well as at the Army Museum at the Invalides in Paris. It can also be ordered directly from the author by contacting him at ianpatrickphoto@gmail.com.

– Temporary exhibition at the Army Museum at the Invalides, June 1 to August 26, 2024. The exhibition is presented under the arcades surrounding the main courtyard. Entrance is free as it isn’t necessary to purchase to museum ticket in order to enter the courtyard. 129 rue de Grenelle, Paris.

© 2024. Interview conducted by Gary Lee Kraut.

All photos © Ian Patrick.

This is a unique and touching narrative that adds dimension to a monumental event so layered with risk and sacrifice and courage, that it takes exposure to multiple facets of the story for those of us not of that generation to grasp. We owe so much, and perhaps we pay our dues by learning more and looking to the individuals as Ian Patrick does by memorializing faces and names.

It is moving that his parents wanted their ashes spread on the beach.