There’s no greater sign of your acculturation in Paris than seizing the right moment to râler (grouse, gripe, grumble) during an in-store complaint, while avoiding the emotional pitfalls and using the proper vocabulary.

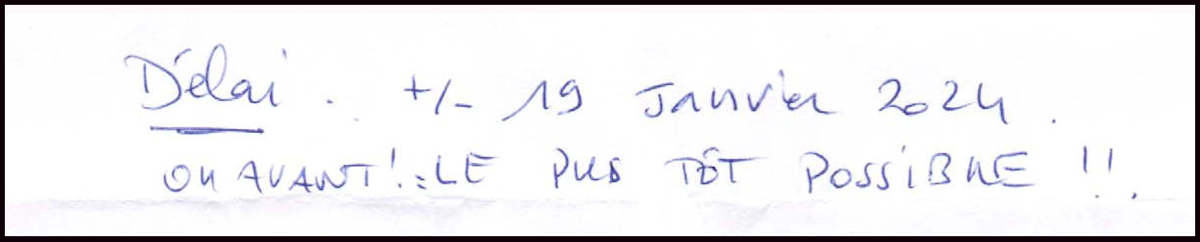

… you’ve looked in many stores for a new armchair and finally select one from BHV Marais, the department store located across the street from City Hall. You choose the fabric and the color. It’s Oct 22. Delivery is promised in handwriting by the mannerly floor section manager: Délai : +/- 19 Janvier 2024 ou AVANT ! LE PLUS TOT POSSIBLE !! – [Delivery] Date: +/- 19 January 2024 or BEFORE! AS SOON AS POSSIBLE!!)–capitals and exclamation points in the original. You have the choice between pick-up at the store or, for 115€, delivery chez vous. The delivery fee seems exorbitant. You’d rather ask a friend with a car to help then take him to dinner. You pay for the chair in full (717€), without delivery, and go about your Parisian life.

Six weeks later, you receive a text message from BHV announcing a delivery delay. The new date is 31 January. You respond that the delay is inacceptable. Your message is ignored. Mid-February, you receive a message announcing that the armchair will be available as of 28 February. This time the message promises, as compensation (dédommagement) free delivery/assembly (livraison/montage), “[normally] billed at 139€.”

A week later, you’ve received no further news of the actual delivery date. It’s now February 21, four months since you paid for the armchair. You’re in the area of BHV so you enter the department store to find someone to speak with. You’re pleased to come upon the same floor section manager who sold you the promise of an armchair. She’s chatting with a colleague.

You greet them kindly: Bonjour. They turn to you with wary expectation. Looking only at the floor section manager, you calmly explain that you’ve received several (plusieurs) delay notices for an armchair that you purchased from BHV Marais four months ago and counting, and still no armchair. She leads you over to her desk and looks up the purchase order, the one with the buoyant and promising capitals and exclamation points, in her own hand: Délai : +/- 19 Janvier 2024 ou AVANT ! LE PLUS TOT POSSIBLE !!

She immediately blames the delay on the supplier, with whom “we always have problems.” Annoyed by the immediate deflection of responsibility, you ask why she kept that detail from you when you purchased the armchair. She says that she didn’t know at the time. You tell her that you have no direct relationship with the supplier, only BHV, so that for you BHV is responsible. “It should arrive next week, monsieur,” she says. “C’est comme ça”—That’s the way it is.

There’s no greater sign of your acculturation in Paris than feeling properly self-righteous and seizing the proper moment to râler (grouse, gripe, grumble). This is it. The battlelines are drawn with a c’est comme ça. Her why-are-you-still-here expression tells you that she thinks that should be enough.

You hadn’t actually intended to râler, you’re not a râleur (grumbler) by nature but by cultural adoption. The floor section manager’s rigid refusal to acknowledge the store’s responsibility is a sign that the moment has come. If you don’t start now, you’ll find yourself wondering while in the metro or in bed or trying to work what you would say or write to best express your frustration with BHV. So you begin with the word that signals to all within hearing distance—the floor section manager and her colleague who is standing nearby. You look the floor section manager in the eye and tell her that the situation is inacceptable. If you’d known it would take so long for the armchair to arrive, you say, you wouldn’t have purchased it.

She returns your square look in the eye as her colleague moves a step closer. She looks to him, he looks to her, they both look to you.

“Un instant,” she says, a sign that she will look on her terminal for proof that the situation is more than acceptable because it is what it is. Indeed, she points at a spreadsheet on her screen and says, “They say it will arrive in one week.” She repeats the offer for free delivery or, she now adds, an 89€ refund. Her tone in presenting the choice is like that of a bored waiter proposing pommes frites or haricots verts. It also bothers you that she’s offering 89€ when the last message spoke of a 139€ delivery value and four months ago she’d offered delivery at 115€. You call her on it. She has an immediate answer: 115€ was an old price. It’s now 89€ for delivery and 139€ if the deliverymen mount the piece of furniture and dispose of the packaging. You tell her that the only mounting required is screwing on the legs.

You’re not sure what to say next and you don’t want to repeat inacceptable so you chose another missile of a word from the râleur’s handbook—you tell her that this is inadmissible.

“I explained the situation,” she says. “Do you understand?”—Vous comprenez? She may or may not be making reference to your accent, but leaving it at that she remains within the rules of engagement. Her colleague inches closer. He can’t seem to focus on his own job until the situation is resolved. You can tell he’s dying to get involved, and he does as he, too, says, “Do you understand?”

What you understand is that you are now culturally obliged to râler further. You say, “I understand that delivery of my armchair is so long overdue that I’d like to a refund.”

“I’ve given you a choice, Monsieur,” she says. “Delivery at home or an 89€ refund and you pick up the merchandise.”

Yes, you know that you’ll presumably soon have your armchair, whether picked up with your friend’s help or delivered with the legs screwed on and the box removed, and that you can then decide for yourself if you ever want to shop at BHV again. So even though you’re unlikely to make any headway against a business as detached, in your experience, as BHV Marais, and a salesperson as doctrinaire as this, with a workplace rubbernecker by her side, you proceed to tell her (you don’t acknowledge him) that she’s presented you with a false choice (un faux choix), one that is intellectually dishonest (intellectuellement malhonnête; it’s an expression that would get you laughed out of Walmart, but here the number of syllables alone signals that you’re a worthy Parisian adversary) since any reasonable choice would involve a full refund (remboursement total).

As her colleague watches, ready to leap to her defense, she tries to goad you into insulting her personally by asking if you thought she “lied” (menti) when she gave you the original delivery deadline (délai de livraison). You know how this works: Calling her a liar (une menteuse) would label you an aggressor and allow her to call victory and store security. The rules of an in-store râlerie require steadfast concrete reasoning. You won’t fall into her emotional trap. So you tell her that you aren’t here to discuss her feelings. You tell her that you were “duped” (dupé) into buying the armchair, with her own handwriting as proof (la preuve). Four months after the original order, you tell her, the honest choice is between a total refund and, you now add, appropriate compensation.

She says, “Do you want to give me a delivery address or not?”

You’ve had your say and there’s nothing more to do here. Despite your elevated heartrate, you coolly give her your address for delivery, should you decide to accept it. Her colleague walks away. Obtaining an 89€ refund sounds too complicated and isn’t an acceptable number anyway. That thought leads you to declare one more time that the situation is inacceptable and to ask now for the contact information for the complaint department.

She writes down the customer service email address.

One might think that any store salesperson properly trained in customer service would know that few clients would bother making a complaint at that point—after all, the chair is due to be delivered in one week and you’ve apparently accepted free delivery—and so would revert to the customary etiquette of farewell, perhaps with a kind assurance that you’ll be happy with your beautiful armchair. If so, one hasn’t shopped in Paris. As she hands you the slip of paper with the email address, and apparently feeling the need for a final power play, the BHV floor section manager says, “Whatever you send will be forwarded to me and you already have my answer.” You now have no choice but to formalize your grievance (réclamation).

At home, you write to BHV Marais customer service. You keep your message short and direct, just the facts of the delay and the unacceptability and inadmissibility of the offer of simply free delivery. You include a scanned copy of the invoice with its capital letters and exclamation points. You make no personal comments about the floor section manager other than to note your incrédulité regarding her parting shot about this réclamation being dead in the water (lettre morte). You conclude by requesting a full refund for the as yet undelivered armchair.

You’ve done your Parisian best. You’ve presented logic, you didn’t once lose your temper, and you’ve made proper use of two of the three most important words in any proper râlerie: inacceptable and inadmissible, using them sparingly, while throwing in an incrédule and an intellectuellement malhônete to let customer service know that you’re no stranger to complaint departments in France. For the time being you’ve refrained from using the third important word, scandaleux, so as to deploy it at the appropriate time with the appropriate interlocuteur.

Two days later you receive a message signed with a guy’s first name inviting you to please be assured that your request is being treated by the head of the concerned department so as to provide you with a response, and thanking you for your understanding. Business-speak for good luck (bonne chance). Since you’re also invited to rate and comment on his response, you give it a 1 of 5 and comment that the client is only reassured when a matter has been fully resolved, and you thank him in return for his understanding.

Several days later, on a Sunday afternoon, you get a phone call from BHV customer service. The female voice is young and sweet and her words are spoken with a smile. You’re offered free delivery (with the legs screwed on and the box disposed of) plus a 60-euro refund. You comment on the strangeness of that number, 60, remarking that it seems to be resting on its way somewhere. She explains that that’s the amount the manufacturer is willing to reimburse and they won’t give more. Since the number is clearly n’importe quoi (rubbish), you tell her that it is inacceptable for BHV to deflect responsibility in this manner. You further tell her that the so-called free delivery isn’t truly a gift because you had planned on picking the armchair up yourself at the store in January. She responds that delivery nevertheless costs BHV and that you could be reimbursed 89€ if you still wanted to pick up the merchandise. Actually, you would like it delivered but are still annoyed that she’s using 89€ as the figure for dédommagement. You tell her that 89€ is n’importe quoi given that BHV’s text mentioned a delivery value of 139€. She says she doesn’t understand. She says this with such innocent-sounding sincerity that you’re about to lose your own thread of logic, when suddenly you remember that you’re the wronged party and have yet to deploy the most important term of any self-righteous râleur. You use it now.

C’est scandaleux, you say.

You take a deep breath then launch into a mild rant about being dupé by BHV from the start and the floor manager’s faux choix, which was intellectuellement malhonnête, and how your many followers, as they say in French, will soon know that this is inacceptable, inadmissible and scandaleux, until finally she interrupts.

Monsieur, she says, you didn’t let me finish my proposition. You’ll get free delivery and assembly of the armchair, 60€ refunded through your credit card, and a 50€ voucher for in-house purchase.

Whether or not the extra 50€ came from your excellent and emphatic use of inacceptable, inadmissible and scandaleux, you can’t tell. But you know that this is clearly the moment for you to stop de râler and to accept that the négociation has come to an end.

So, with the proper air of resignation, you accept her proposition. And like that, the unacceptability and the scandalousness of the situation disappear like vampires at sunrise.

Once you’ve accepted the offer, you and the customer service rep discuss how and when all this will occur. Her voice is even more soothing and reassuring than before as she explains the timing: the armchair delivered next week, the voucher from BHV within 24 hours, the refund from the manufacturer in 2-4 weeks*. You can nearly smell the floral scent of her perfume. Your own tone is melodious, with a hint of sandalwood, as you provide her with your email address and mailing address. When she says that she knows where that is, you tell her to stop by sometime to see your armchair. The banter is so light and cheery that you nearly forget that you’ll both be glad when the conversation is over. But the time has come for her to ask if there’s anything else she can do for you today, for you to say, “No, that’s all,” and to wish each other un bon dimanche, a good Sunday. She will then return to other dissatisfied clients and you can now decide how strongly you want to advise against ordering anything from BHV Marais.

Very strongly indeed.

© 2024, Gary Lee Kraut

*Six weeks later, when the 60€ has failed to arrive, you wonder if BHV has pocketed the refund from the manufacturer.