Hervé Huet pulls out his pocketknife and slices open the vacuum pack of headcheese that he’s brought to share with the group this Tuesday morning at the bar counter of Le Vaudésir. He arrived first because he’s the group’s president. Les Joyeux Mâchonneurs du Vaudésir, they’re called, more or less meaning the merry morning pig-and-innards-eaters of Vaudésir. Each Tuesday the little gathering elbows up to the arc of the old zinc counter of this 125-year-old bistro between 10:15-11:55AM to share food, drink, company and good humor before proceeding with their day, either separately or, as in today’s case, together.

Non-members stop by the bistro for morning coffee or a pre-lunch aperitif, unaware of the planned, informal gathering of the Joyeux Mâchonneurs. But they might as well be a part of the group as Hervé slices off chunks of headcheese to offer them a taste. Headcheese and coffee? Maybe. Headcheese and wine? Sure.

Tristan Olphe-Galliard arrives with a bottle of wine that he sets on the counter as his contribution to the morning gathering of the Joyeux Mâchonneurs. Before sharing the wine, though, he shares the story of why he’s arrived later than planned: The mechanism to open the door to his building was stuck, so to get out he had to crawl like a thief from the window of a neighbor’s apartment. And he definitely can’t stay with us past lunch, he says, since he has to… Right.

He’s brought a red Mentou-Salon, a cousin to Sancerre, from the eastern winegrowing area of the Loire Valley. A brief explanation is enough—this is a social gathering, not an informational assembly. It’s easy-drinking wine, a pinot noir of the cherry-tinged kind. Tristan is an ambassador for the network of Bistrots Beaujolais, bistros which are themselves ambassadors for Beaujolais wines or at least have some on their wine list. He’s also a freelance photographer, as well as a member of the Francs-Mâchons, a non-profit association with a natural affinity to the Joyeux Mâchonneurs but more organized and with a distinct appetite for Beaujolais wines. But Triston is only partially on duty this morning; not duty enough that he feels obliged to bring a Beaujolais to this gathering but dutiful enough to invite me to meet him here to discuss my plan to visit some of his Bistrots Beaujolais over the next two months. Research.

But first things first. The barman opens the bottle.

You don’t need to be a member of the Joyeux Mâchonneurs to attend the Tuesday morning gathering. You don’t have to eat pig. You don’t even have to arrive joyeux, though hopefully you’ll leave that way. All you have to do is bring something sharable to eat or drink (keep it simple) or else buy a(n inexpensive) bottle of wine at the bar. And, no, the point is not to go on a pre-noon bender. It’s enough to toast with a sip or two—a bistro glass is small anyway. It’s the spirit that’s generous, not the pour. You can put your hand over your glass in refusal at any time (though it will likely be filled as soon as you look away). Seriously, order coffee if you like.

Bistro life

The word bistrot (with a final t in French) encompasses a range of restaurants and eatery-drinkeries that emphasize traditional French food and wine. In English-speaking countries, bistro may carry an air of pretention, which doesn’t belong in France. At its heart, the French bistro (let’s leave out the t here) is an unpretentious neighborhood gathering place for traditional, homemade food and inexpensive drink. “Traditional, home-made food” itself can vary within limits and budgets. And in the relatively wealthy city of Paris, “unpretentious” is itself a term that’s up for grabs, while “inexpensive” will depend on the neighborhood. In any case, a bistro should feel down-home rather than upscale, even those that attract an upmarket crowd.

In terms of opening hours, there are two types of bistros: a bistro that’s open only for lunch and dinner, i.e. a bistro as restaurant alone, and an eatery-drinkery bistro, such as Le Vaudésir, where food is served at specific hours yet one can enter throughout the day for liquid nourishment (and, if you’re a regular or ask kindly, maybe someone can make you a sandwich or give you some headcheese or a hard-boiled egg). I’ve met with Tristan this morning in soliciting his help constituting a list of the latter kind of bistro, the historic but not necessarily bygone bistrot de quartier, the neighborhood eatery-drinkery bistro. The archetype of a neighborhood bistro such as Le Vaudésir serves a social function as a gathering place, an outlet for extroverts, a refuge for the lonely, escape from your spouse or kids, comic relief for the observer, a place where a regular is recognized, etc.

In the densely populated and much-visited city of Paris, “neighborhood” doesn’t mean that the patrons all live within three blocks of the bistro. At lunchtime, neighborhood bistros are frequented by those who work in the area but live elsewhere. And the dinner crowd may be a mix of neighborhood residents, Parisians with a city-wide vision of dining out casually, and travelers staying in nearby hotels.

The neighborhood bistro of the eatery-drinkery kind may not have Bistrot written in its name or on its awning. Even a café or a brasserie or a meat-and-potatoes/sausage-and-lentils dive can be considered the local bistro if it serves an unpretentious social function (gathering place, refuge, escape, etc.) and presents the other elements associated with the bistrot de quartier: traditional cuisine and cheap or modestly-priced drink, conviviality, a changeable atmosphere morning to night, and a smattering or more of Joyeux Mâchoneurs or their like. Just as Joyeux Mâchoneurs by any other name would be just as joyeux, a bistro by any other name would be just as … bistro.

I’ve neglected to mention the other essential element to the type of bistro that I’ve come looking for: an on-site owner. Not just any on-site owner, but an on-site owner as conductor, MC, security guard, arbitrator, sphinx, ultimate judge, merchant and boss. He may stand stoically on the raised platform of the bar as he surveils the room. He may join in the banter of his regulars. He may raise a glass with others. He knows his regulars. He knows when to be wary and when to be welcoming. At Le Vaudésir, he’s Christophe Hantz.

By the bar counter there’s a list of names and dates of owners at this site since 1896, beginning with a certain Forestier, who sold wine. For much of the first half of the 20th century, coal and wood were also sold here. (The second room, behind the bar, is where they were stored.) In 1993, the owner at the time renamed the bistro Le Vaudésir, after one of the seven “climats” of Chablis Grand Cru. Vaudésir Chablis was still a relatively inexpensive at the time, but it’s now too pricey to belong on the selection here. Christophe has been at the helm of Le Vaudésir since 2001.

Michelle Steiner, the chef he hired that year, joins us for a drink before returning to the kitchen to make final preparations for lunch service. “Christophe and I are like an old couple that’s never copulated,” she says. Christophe isn’t yet around to give his take on their relationship.

La Fête du Livre Bistrot at Le Vaudésir

There is no off-the-beaten track in Paris; there are just streets we haven’t yet ventured down and doors we haven’t yet opened or times of day or night that we haven’t yet been there. So it isn’t to go off the beaten track that I’ve returned late the same day by taking the train to Denfert-Rochereau, walking 10 minutes south, and turning left onto rue Dareau. The street leads film-noir-like to a door beneath the railroad tracks. The first room is so crowded that I can’t even push open the door. I enter through the second door a few yards further down. No, I haven’t gone off the beaten track to make my way back to Le Vaudésir this evening; I’ve come to attend the Fête du Livre Bistrot, a celebration of books about bistros, their authors, and, above all, bistros themselves.

Not all Parisians go in for such places, as the diminishing numbers of restaurant-bar-café bistros show. They’re too old-fashioned for some; the cooking isn’t contemporary enough for others; they prefer to mingle elsewhere, differently or with a younger crowd; if there’s a squat-toilet that may not be to everyone’s liking. “Local” itself may have lost its significance for those who prefer screen time. The foreign visitor may be intimidated to stand at the counter with piliers de bar (literally bar pillars, i.e. barflies) or sitting elbow-to-elbow at a table beside animated strangers in unintelligible conversation. No, the atmosphere of the eatery-drinky neighborhood bistro isn’t for everyone.

But it is for everyone here this evening, chatting with each other and with the authors, purchasing books, examining the works of two photographers, drinking the Saint Pourçain wines brought by the producer who’s serving them at the bar, reaching for the plate of headcheese and pâté on the bar counter. Tristan is here, Hervé is here, and so are other members of the Joyeux Mânchonneurs.

I speak with the winegrower of the Saint Pourçain as he serves me a glass. The wine is free this evening. Christophe is also behind the bar. I say hello. He raises his glass and offers his infectious smile, though he may or may not recognize me.

I chat with Alain Fontaine, owner of Le Mesturet, in the 2nd arrondissement. Le Mesturet’s awning reads Bar à Vins and Restaurant but it’s bistro enough for me. Alain spearheads a non-profit association whose mission is to promote and defend the idea that the art de vivre of bistros and traditional cafés of France deserve recognition as “intangible cultural heritage.” He says that foreign visitors, Americans in particular, are more prominent supporters for bistro life than the French themselves. (Perhaps, I think, because we like a good cliché or because we don’t have these at home.) Earlier this year he hosted at Le Mesturet a launch part for Café Society: Time Suspended, the Cafés & Bistros of Paris, a collection of photographs by Joanie Osburn, a frequent visitor to Paris from San Francisco. I tell him that I’ll be stopping by Le Mesturet to speak with him soon in the context of my own research. Whenever you want, he replies.

I run into free-spirited food writer and guide Guillaume Le Roux, whom I knew from restaurant press events a dozen years ago and haven’t seen since. We recognize each other immediately, briefly catch up, and promise to get together soon.

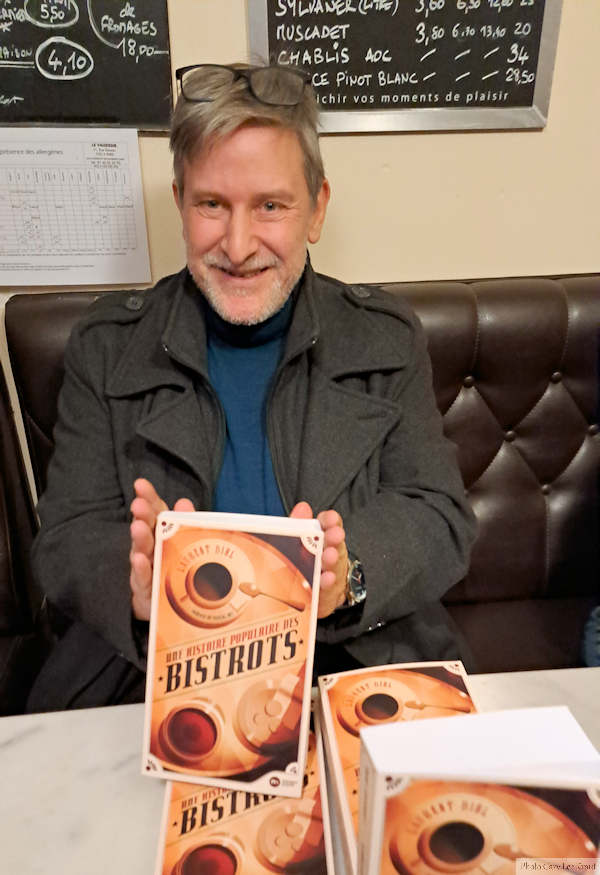

I speak at length with historian Laurent Bihl, author of Une histoire populaire des bistrots and gladly weigh myself down by purchasing his 800-page book.

I greet Gérard Letailleur, author of “Histoire insolite des cafés parisiens” and “Si Montmartre et La Bonne Franquette nous étaient contés,” whom I’d previously met at Aux Sportifs Réunis-Chez Walczak, a historic bistro in the 15th arrondissement.

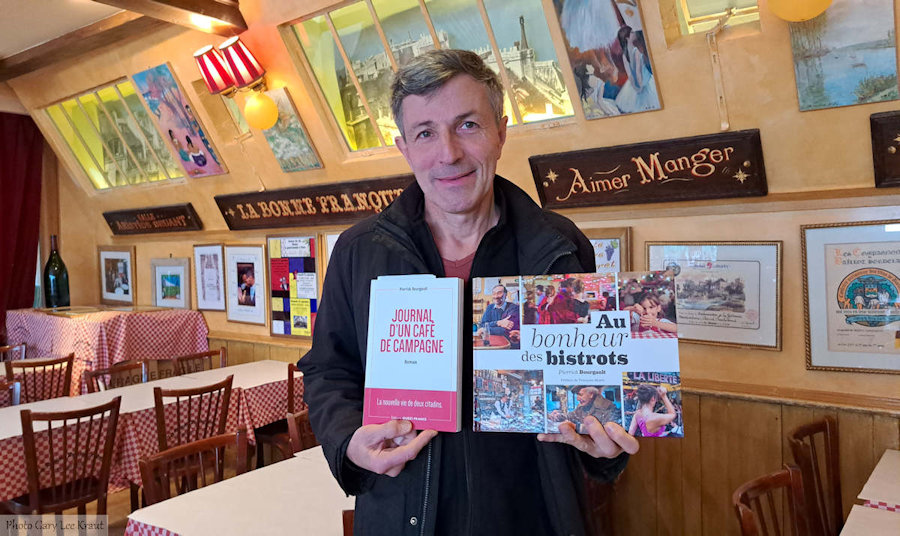

I nod to Pierrick Bourgault who’s in intense discussion with someone interested in his work as a photographer and writer. Patrick explores his love and appreciation for bistros in both non-fiction and fiction. Among other publications, he’s the author of Au bonheur des bistrots, which pays homage through photographs to the men and women who run countryside cafés, and the novel Journal d’un café de campagne. We’d previously met at the unmissable La Bonne Franquette at the top of Montmartre.

I meet Benjamin Berline, who’s part of the team working with well-known French food writer Gilles Pudlowski. He gives me a copy of the 2023 edition of the Petit Pudlo des Bistrots, a booklet that brings together 107 recommendable Parisian bistros (with an introduction by Alain Fontaine).

I find Tristan outside and thank him for setting me on my way for my bistro research. I tell him I’ll see him soon. (Though Tristan and I don’t run in the same circles we do manage to cross paths often.) I tell him I’m leaving. He says that he’ll be leaving soon too. Right.

Le Vaudésir, 41 rue Dareau, 14th arrondissement. Metro Saint-Jacques or Metro/RER Denfert-Rochereau. Closed Monday evening, Saturday lunch, Sunday. Cash only.

© 2023 by Gary Lee Kraut