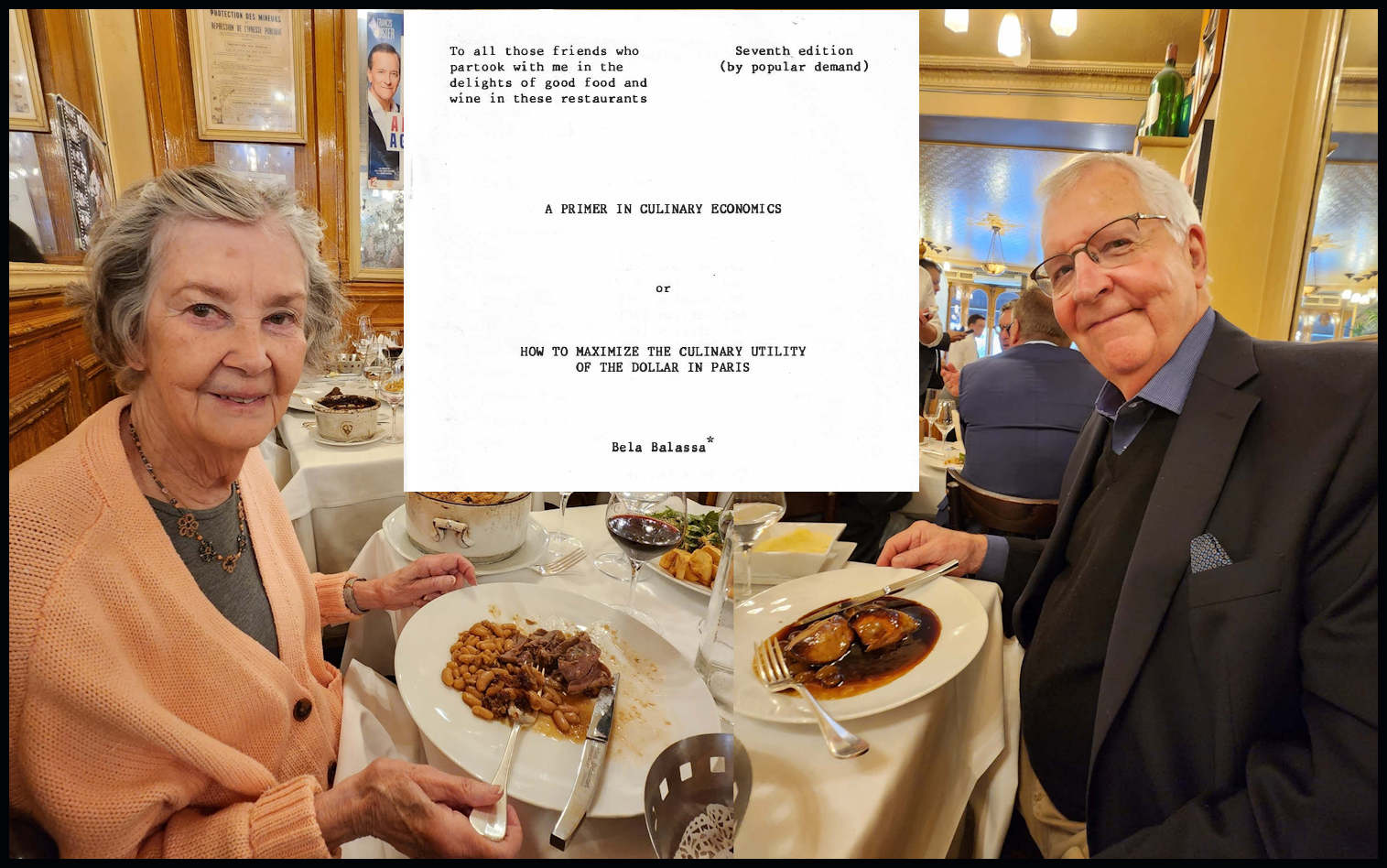

Culinary sleuths Richard and Judy Fritz set out on a deliciously intriguing culinary adventure in Paris as they followed in the footsteps of a little-known restaurant guide written in the 1980s by renown economist Bela Balassa, leading to their discovery of six notable and enduring restaurants to consider for your own culinary adventures.

I could have used numerous sources to guide my selection of restaurants in Paris when visiting this past spring—the Michelin Guide, the New York Times, reliable bloggers, returning friends, or this very website—but as an economist I chose to follow in the culinary footsteps of a fellow economist. Not just any fellow economist, mind you, but a pioneering economist whose serious academic work impressed me, a fellow who had a good appetite, a keen knowledge of traditional French cuisine, a taste for wine, and a compulsion for keeping detailed notes on the 250 or so restaurants that he had the opportunity to experience in Paris over the years while working for the World Bank.

Bela Balassa, a Gourmet Economist

I was first introduced to Bela Balassa’s academic research while a graduate student at Georgetown University in 1975. International economics was not my specialty, but we all read Dr. Balassa’s groundbreaking work on the terms of international trade. Ultimately, his research led the way to fundamental changes in World Bank policy.

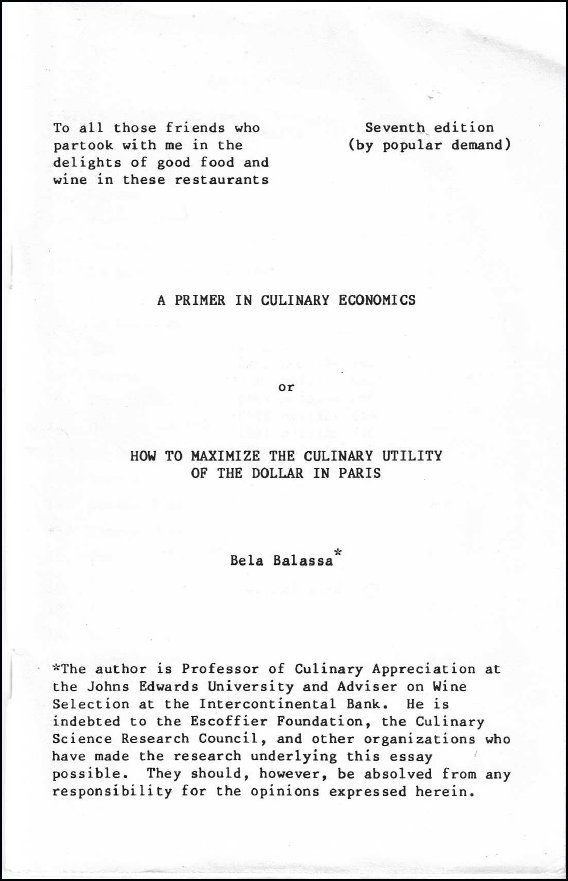

Decades later I would come across a booklet that he printed up privately, a restaurant guide titled A Primer in Culinary Economics or How to Maximize the Culinary Utility of the Dollar in Paris. He ultimately produced eight editions of his booklet, the last in 1987.

In his “Preface or Let the Reader Beware,” Dr. Balassa wrote in the 1985 edition, “This essay provides an appraisal of twenty-five restaurants in Paris, carefully selected among over two-hundred-fifty the author has visited between 1959 and mid-1985… The author has spared no effort in selecting, checking and rechecking the restaurants on the list, without regard to his caloric (and cholesterol) intake.”

“[This] has been written,” Dr. Balassa noted, “for the benefit of those who wish to maximize the (culinary) utility derived from eating, suitably accompanied by wine, and subject to a budget constraint.”

“Maximize utility” is a term that speaks to me as an economist, but I recognize that most travelers visit Paris in search of pleasure rather than utility. And rightfully so. In fact, the fundamental proposition in microeconomics is that consumers attempt to achieve their highest satisfaction (economists call it “utility”) by consuming a bundle of goods, subject to a budget constraint. Of course, Dr. Balassa’s use of economic terms is partially tongue in cheek here; he never actually provides details about his calculations of a quality-price ratio. Basically, he set out to maximize his personal satisfaction from wining and dining in Paris, subject to his own (experienced) appetite and (healthy) budget constraint, and then to share his sense of a good, even great, meals in Paris with family and friends. Dr. Balassa had a personal notation system for restaurants with 10 being the highest possible “grade” and 5 being the lowest acceptable for inclusion on his list. He was serious and systematic enough in his approach to include only establishments that he had visited at least twice.

Born in Budapest in 1928, Dr. Balassa immigrated to the United States from Hungary in 1956 after the Hungarian Revolution was crushed by Soviet tanks. He was appointed assistant professor of economics at Yale before becoming a professor of economics at Johns Hopkins University. He also worked as a consultant for the World Bank and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which provided him with the travel stipends that he used as the basis for his budget constraint in his culinary explorations in Paris, primarily the latter. He died in 1991.

In the spring of 2020, my last semester teaching at Georgia Tech, I acquired with the help of one of my students the 7th edition of Dr. Balassa’s Primer, printed in 1985. It’s more a booklet than a book, printed on a standard 8.5” x 11” paper, folded in half and stapled in the center. There are 66 pages of text discussing the restaurants and ten pages of a Glossary of Culinary Terms.

Dealing with the Danger of Using an Old Restaurant List

There are inherent dangers to using a decades-old restaurant list for guidance, but I willingly accepted the pitfalls in the name of culinary adventure, and I was rewarded for my efforts by the six delicious meals that I share below and that you may find helpful in seeking to maximize your own culinary utility. I should say we were rewarded since my partner in this adventure was Judy, my wife of fifty-four years, who has a doctorate in French and enough experience in French cuisine to be an excellent culinary sleuth.

There are 25 restaurants listed in the 7th edition, but 38 years in the Parisian restaurant business had taken its toll on Dr. Balassa’s recommendations. In undertaking the adventure of following in Dr. Balassa’s culinary footsteps, Judy and I decided that in order to be true to the original selection we would only go to restaurants with the same name and location as those that he recommended in that 7th edition. Six of the original 25 restaurants made the cut. In late April 2023, we left for Paris having rented an apartment for 28 days and made reservations in those remaining six restaurants.

Emphasizing the personal nature of his Primer in Culinary Economics, Dr. Balassa, who passed away in 1991, described various dishes he had shared with his family. He included what his son and daughter particularly liked on the menu of various restaurants. So I decided to seek them out in preparing our adventure. Through some diligent effort and a lot of luck, I made contact with Bela’s widow, Carol, to share the blueprint of our culinary adventure. She in turn shared our plan with her son and daughter. Carol’s son then sent me excerpts of the Primer’s 8th and final edition, from 1987, which led us to add two more restaurants to our list, bringing the total of restaurants still existing under the same name at the same address to eight.

His/Our Budget

Naturally, a World Bank travel stipend for a consulting economist of Dr. Balassa’s stature did not relegate him to cut-rate cafés, crepe stands, kebab stands and all-you-can-eat Chinese buffets. It gave him a seat at an array of decent and fine establishments, including some Michelin-starred tables.

In his preface, Dr. Balassa indicates that his “self-imposed limit” when considering the price of a meal in 1985 was $70 for a meal for two people. He writes, “Still, staff members of international organizations will have their travel expense account returned for ‘clarification’ if they eat two meals a day at these prices. To avoid such an eventuality, they should limit themselves to a daily meal at one of the restaurants, a spartan breakfast, and a quiche Lorraine for lunch.” The average value of one U.S. dollar in 1985 is worth $2.84 adjusted for 2023 prices. Therefore, Dr. Balassa’s $70 limit for a meal for two is adjusted to $198.80 at today’s prices, or approximately 184€ while I traveled this past spring. That, as you’ll soon read, allowed for some excellent meals.

Revisiting A Primer in Culinary Economics: 6 Choice Restaurants

In following in Bela Balassa’s culinary footsteps, Judy and I came to feel an affinity with him, and before long we were referring to him not as Dr. Balassa but as Bela. I therefore use his first name for the remainder of this article. Though we would later give “grades” to these restaurants, as Bela had done, I list them here simply in the order in which we visited them. Unlike Bela, we only dined in each once. And though we may not have the range and depth of culinary experience to draw on that he did, we feel experienced enough in French cuisine, particularly traditional French cuisine, to share our point of view on the restaurants we visited.

La Petite Auberge

La Petite Auberge, 13 rue du Hameau, 15th arrondissement

Bela called this a “very excellent restaurant,” and nearly four decades later we found that it was very good indeed. We came to expect that Bela’s recommendations leaned to the traditional neighborhood type restaurant. This certainly fit the bill. It is a bit out of the way unless you’re in Paris for a trade show at the Parc des Expositions (Porte de Versailles), a 5-minute walk from the restaurant. The home stadium of Paris’s Stade Français rugby team is two miles away. Rugby posters decorate the unassuming interior space of this restaurant that has stood the test of time.

We had a French guest visiting from the Beaujolais region who was eager to join this culinary expedition. We started by sharing a pâté de canard (duck pâté) with radishes and house-prepared cornichons. The combination was well balanced with the duck fat and salty cornichons. For our main course we ordered blanquette de veau riz (veal stew with rice), noisette d’agneau poêlée (a pot of nuggets of lamb) and escalope de veau normande (Normandy-style veal cutlet). To our delight, the menu announced that Tous nos plats sont accompagnés de frites maison (all dishes come with “pommes frites”). Our guest quickly approved and compared the meals to those her grandmother prepared when she was a young girl. The white stock was thick and savory on both veal dishes. The lamb was well-prepared, served medium rare with a broccoli floret. The fries were hot and had a near-perfect crunch when consumed. For dessert, we ordered crème brulée, tarte aux pommes, and panna cotta. The deserts were unremarkable. We all would have preferred just another round of the pommes frites. Overall, however, Bela had steered us right for a meal of unpretentious French comfort food with authentic flavor… at an easy-going price. Our luncheon meal for the three of us came to 107.80€, or about $116.42, well within the Primer’s budget limit. Of course, he might have added more wine and perhaps a digestif in keeping with his “very excellent” experience.

Benoit

Benoit, 20 rue Saint-Martin, 4th arrondissement

Our second restaurant was a highly anticipated affair. Our daughters had been following our Paris planning process and were eager to contribute to the enterprise. In our 2022 family Christmas exchange we found a gift certificate for a six-course tasting menu for restaurant Benoit.

Subsequent to Bela’s dining here, Benoit joined Alain Ducasse’s restaurant portfolio and then earned one star in the Michelin Guide. Of the restaurants remaining from his Primer, it had Bela’s second highest ranking. He wrote, “Benoit may be grouped with Chez Pauline and Pierre Traiteur. All three provide traditional cooking of high quality at reasonable prices… I rate Benoit a notch above Pierre Traiteur, with Chez Pauline slightly behind.” Benoit is still open for business at its Bela-era location, in fact its location since 1912, while the other two are not.

Bela warned in his booklet that lunch rather than dinner was the best opportunity to stay within budget. However, at Benoit we reserved for dinner since that’s when the Menu Dégustation 6 Temps that we’d been gifted is offered.

While the neighborhood (it’s near the Centre Pompidou) has changed dramatically since the restaurant opened over one hundred years ago, once inside, among the woodwork, the red velvet seats, the brass railing and the engraved glass windows, we immediately felt that we’d entered a neighborhood of yore. The meal started with notre pâté en croute, pickles de legumes (house pâté in a pastry crust with pickled vegetables), served with warm slices of baguette. The fish course was next. It was the tasty combination of filet de bar doré, artichauts poivrades et roquette savage (filet of sea bass, sauteed with artichokes and wild arugula). The main plate arrived with a generous individual portion served in a copper pot. It was sauté gourmand de ris de veau, crêtes et rognons de coq, foie gras et jus truffe (sauteed veal sweetbreads, rooster cockscombs and kidneys, with foie gras and truffle juice). The description itself was a mouthful, and none of our previous experiences in traditional bistro fare had led us to such an unfamiliar combination of flavors and textures. We would probably not have ordered this as a main course if we were ordering off the menu, hence a reason to risk a tasting menu. The next course was simply and delightfully fromages de France (French cheeses). It was certainly a good idea to follow the pot of sweetbreads, cockscombs, and kidneys with creamy French cheese. Sorbets de la manufacture (sorbets from Ducasse’s ice cream and sorbet “factory”) followed the cheese course. A plate of profiteroles Benoit, sauce chocolat chaud followed.

The whole evening had been a rewarding adventure in Paris dining. Furthermore, the staff was interested in hearing about our exploration of the “professor’s Paris restaurant recommendations.” The chef and maître d’hôtel signed both our tasting menu and Bela Balassa’s booklet.

In the section titled “Introduction or a Bit of Nostalgia,” Bela discusses the importance of the “quality-price ratio.” He explains that many establishments were dropped from his recommendations over the years either because they became too expensive or because the quality had deteriorated, or sometimes both. Benoit has certainly increased in price over the years but I suspect that Bela would have kept it on his list these many years later. Our tasting menu for two was priced at 190€, or approximately $205.20, only slightly above his limit. Had we ordered off the menu instead of using our daughters’ gift certificate, we could have had a very fine meal within the limit.

Le Récamier

Le Récamier, 4 rue Juliette Récamier, 7th arrondissement

Our third stop was located on a pedestrian cul-de-sac off rue de Sèvres, which is dangerously close to the Bon Marché department store and Gérald Darel for anyone for whom well-heeled brand shopping might distract from a culinary mission. Judy nevertheless maintained her focus before seizing the shopping opportunity after lunch.

Récamier refers to a certain Juliette Récamier whose unfinished portrait by Jacques-Louis David hangs in the Louvre. Madame Récamier, as the portrait is called, was a French socialite whose salon drew people from the leading literary and political circles of early 19th-century Paris. Interestingly, David stopped working on her portrait in 1800 when he learned that François Gérard had been commissioned to paint her portrait. Gérard’s portrait hangs in Paris’s Musée Carnavalet. By all accounts and as seen in her portraits, Madame Récamier was something special. On the restaurant’s web page, they make sure their patrons are aware of this heritage, saying, “Today, her spirit is still alive … The elegance of Madame Récamier’s salon lives on.”

Bela recommended a table on the terrace and we were able to secure one. (The terrace is removed from car traffic.) His recommended dining options were beef and fish. He wrote, “the daily additions to the menu includes fish dishes,… [the chef] gets first-quality products every day.” The freshness still appears to be true, but the menu Bela read had evolved over the past 38 years. The ones in our hands contained a substantial list of savory soufflés, which have been a hallmark of the restaurant for the past ten years. We promptly ignored that list, until the dessert page.

Judy started with soupe de carotte au curry (curried carrot soup), while I ordered salade d’artichauts poivrade á l’huile d’olive citronnée, Parmesan Reggiano (artichoke salad with lemon olive oil and parmesan cheese). The dish that was the highlight of Judy’s Paris dining experience that month came next: filet de bar grillé, légumes de saison, sauce olivade et tapenade (grilled sea bass with seasonal vegetables in an olive and tapenade sauce). The fish and sauces were well prepared, but Judy especially gave the dish two thumbs up for the quality and quantity of the seasonal vegetables. Based on Bela’s recommendation, I ordered pavé de veau, pommes de terre sautée, sauce morille (veal with sauteed potatoes in mushroom sauce), which was nearly as gush-worthy as Judy’s choice. For dessert, we shared a soufflé à la mangue, sorbet fruits rouges (mango souffle with red-fruit sorbet). Bela had warned, “…watch out for the desserts. The meal does not come cheap and you are easily up to our self-imposed limit if you take one of the excellent Burgundies,” a warning that if you have an expensive bottle of wine, your budget may not afford dessert. We had not taken an excellent bottle of wine with our meal, rather we each had a pleasing glass of Macon Villages and therefore felt completely guiltless sharing our very satisfying dessert. Our luncheon came to 138€ or about $140, so there would have been room within the budget had we wanted more wine and/or a second dessert.

Joséphine Chez Dumonet

Joséphine Chez Dumonet, 117 rue du Cherche-Midi, 6th arrondissement

Originally called Joséphine, this restaurant opened in 1898. When the Dumonet family took over the business decades ago they added Chez Dumonet to the name. The family still owns the restaurant. In adding this entry to his list in the 8th edition, Bela referred to it as “basically a bistro, and a good one.” As we knew by then, Bela was a huge fan of classic bistro fare. He recommended several dishes including “foie gras frais de canard – outstanding.” Reading Bela’s reviews, it appears that he never met a homemade foie gras he didn’t like.

The restaurant was featured in the 2013 film Le Weekend when the two main characters return to Paris to celebrate their 30th wedding anniversary. They search for the classic French bistro, dismissing one place after another because they are too big, too pricey, too empty, too touristy, or too stuffy. Then they find the curtained restaurant on a quiet one-way street with small wooden tables covered with simple white tablecloths. Voilà, there is Joséphine. We certainly agreed.

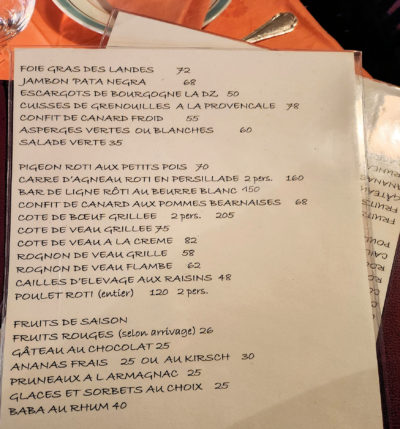

We had house guests from the Netherlands who joined us for our luncheon reservation. Aspèrges blanches (white asparagus) was in season, so we all started with the dish. We shared the foie gras de canard frais maison, and although our house guests aren’t typically as fond of foie gras as we are, we were all pleased with Bela’s recommendation. Having another couple at the table gave us the opportunity to taste four classic bistro dishes for the main course: confit de canard maison, cassoulet maison, boeuf bourguignon aux tagliatelles, and foie de veau, vinaigre de framboise. Regarding the latter, I would not usually order calf’s liver, but Bela had high praise for the dish and I’d set out to follow in the great gourmet economist’s footsteps, so on I marched… and it was melt-in-the-mouth delicious. Judy had the cassoulet, a meat and bean stew, though perhaps not for the sake of Bela’s memory but rather for her own since during her teaching career she was involved in numerous student exchange programs between the sister cities Atlanta and Toulouse, and cassoulet is a specialty from Toulouse that Judy enjoyed whenever she visited that pink-tinged southwestern city. Our companions were very satisfied with their French comfort food of duck confit and beef Burgundy. The classic French dishes prepared to perfection at Restaurant Joséphine were a hit around the table. To our discredit, we did not save room for dessert, what with the two appetizers, but I trust that Bela’s two dessert recommendations are still valid: the tarte fine chaude aux pommes (hot thin-crust apple pie) and the millefeuille Jean-Louis. The price of our four meals came to 258€. Therefore, the two-person budget of 129€, or about $139.32, which would have been within budget even with the dessert.

Divellec

Divellec, 107 rue l’Université, 7th arrondissement

Jacques Le Divellec moved from the La Rochelle on the Atlantic coast to the Esplanade des Invalides in Paris in 1983, bringing with him his appreciation for fish and seafood and his talent for preparing them. Bela would have known the restaurant when it was called Le Divellec and Le Divellec himself was in the kitchen. The chef retired in 2013 and the restaurant was taken over several years later by Mathieu Pacaud, who removed the Le but kept the Divellec. The restaurant currently has one Michelin star. Admittedly, our rules were to follow in Bela’s footsteps only when a restaurant remained with the same name in the same location as when he dined there. But no need to be too picky for a mere Le.

We attended the American Church of Paris that Sunday. The restaurant is a short walk from there. Bela reports a pleasant décor at Le Divellec that “gives the impression of a yacht club.” I shall reverse the compliment, saying that this yacht club gives the impression of Divellec.

The employees at Divellec were most curious about our culinary adventure. During the meal they offered us tours of the wine cellar, the private dining rooms and the kitchen.

Bela recommended starting your meal with fresh oysters, and so we did to our great pleasures. Next, we shared calques bar, bonbons de pomme vert, citron caviar (thin layers of sea bass marinated with green apples and lemon), a house specialty. The layers are sliced so thin that the sea bass looks translucent. The dish was deliciously delicate. The next course we considered our main, though it could have easily served as another appetizer. We shared palourdes, gratinées au thym citron (baby clams prepared au gratin with lemon thyme). We are very fond of mussels prepared in a similar fashion but the clams outperformed the dish of mussels we had recently had at another restaurant. After the clams, we enjoyed a delightful soufflé au chocolat (chocolate souffle).

Bela noted, “White wine is de rigueur with seafood and fish, and Le Divellec offers a wide selection.” We followed his advice—and the sommelier’s—and enjoyed a bottle of Château Reignac from Bordeaux. It proved an excellent complement to our three courses of seafood. At 65€ the Château Reignac wasn’t terribly expensive by Paris standards, yet it pushed the bill beyond Bela’s limit. The total came to 218€, or $235. We could have held the budget line with just a glass of wine, as we did at all the other restaurants, but Paris calls for a little splurge every now and then. All told, we could see—and taste—why Bela awarded Le Divellec his highest score, 9 out of 10. We also concluded that this was a restaurant we would most like to bring our family to upon our return to Paris. Sea food, chocolate soufflé, and a bottle of Château Reignac for a Sunday lunch. What could be better?

L’Ami Louis

L’Ami Louis, 32 rue du Vertbois, 3rd arrondissment

When Bela was rating his restaurants 38 years ago, L’Ami Louis’s chef, Antoine Magnin, was 78 years old and Bela worried that “the time may not be far when he decides to retire. Yet, his restaurant should not be missed by anyone who appreciates traditional French cooking in a vieillot bistrot atmosphere. Indeed, there are few bistrots like L’Ami Louis left in Paris.” Bela would be pleased to learn that the famous little bistro lives on in the finest tradition and continues, as Bela wrote, to serve “genuine, tasty food as one imagines having in our grandmother’s days.”

With just 14 tables, the restaurant is quite small. Reservations are required, not just because it is a marvelous bistro, but it also has been visited by Bill Clinton, Jacques Chirac, Alice Waters, Francis Ford Coppola, and recently, Vice President Kamala Harris and Second Gentleman Douglas Emhoff. I went alone for lunch while Judy was cashing in on a Mother’s Day massage gift from the daughters. Bela wrote, “I recommend that you order the following dishes, to be served in succession: foie gras, confit de canard, and agneau de lait” (foie gras, roast duck breast, and suckling lamb). He also said that you can stay within your budget for two, … “provided that you share some of the gargantuan portions.” Dining alone meant making adjustments, beginning with the notch of my belt, for I had no one to share with.

I started with a simple salade verte (a lettuce salad). This was my initiation to the “gargantuan portions.” The salad bowl brought to the table included at least two heads of Bibb lettuce. The salad bowl was enough for a family of four. But it was only lettuce, and the Dijon vinaigrette, lightly applied and evenly distributed, made it effortless to keep having just one more bite. My main course was always going to be confit de canard aux pommes bearnaises (roasted duck breast with potatoes in bearnaise sauce). I wasn’t tempted by the suckling lamb, not because I wouldn’t have liked giving it a try in Bela’s honor but because it was not on the menu. Anyway, the duck was plenty. I sure could have used Judy’s help with these first two courses. I had only had duck confit a few times previously but this serving exceeded my previous memory of the dish. It had the traditional crusty top with most tender breast meat. The bearnaise sauce drizzled over the potatoes was an excellent complement to the duck breast. The salad bowl, the crispy duck breast, and potatoes with bearnaise sauce were all in front of me, when there appeared before me a large bowl of pommes de terre frites (French fries). A nearby table of six diners were enjoying roast chicken with pommes frites and their bowl of fries was just as large as mine! Where was Judy when I needed her? I continued to enjoy all the flavors on my table to the best of my abilities. And to further exercise my abilities, I then ordered dessert, a gâteau au chocolat (chocolate cake), and coffee. Shortly, I was rewarded with a glass of brandy. I think the restaurant’s servers were showing their appreciation for a customer who had made the most of his lunch. The cost of the meal was 137€, or about $148. Times two that would have been well beyond budget, but here I was lunching alone. I could use the justification that the “gargantuan portions” would have easily served the two of us, but no need to justify. I can’t imagine that the World Bank would insist that their consulting economist eat every meal with company. He, too, must have sometimes struck out on his own.

Maison Rostang and Au Trou Gascon

L’Ami Louis proved to be the last restaurant we tried from Dr. Bela Balassa’s recommendations. For various reasons we were not able to fit in the remaining two establishments. They will have to be on our list the next time we are in Paris.

One of them is Maison Rostang, 20 rue Rennequin, 17th arr., which now has two Michelin stars and may well be above this project’s budget limit. Bela knew the restaurant as Michel Rostang when its founding owner-chef of that name held the reins. Rostang now operates a mini-culinary empire while having handed the keys to the kitchen at Maison Rostang to Nicolas Beaumann.

The other is Au Trou Gascon, 40 rue Taine, 12th arr., which was highly rated in the 7th edition but was dropped in the 8th edition, perhaps because in the intervening year (1986) chef Alain Dutournier, without abandoning Au Trou Gascon, took up arms at the more luxuriant Le Carré des Feuillants. (The Feuillants closed in 2021 yet the Trou still exists.)

Final Grading

On his personal scale from 1 to 10, Divellec received the highest grade of the restaurants that remained active, a 9.0. Benoit was given an 8.5. Both Le Récamier and L’Ami Louis received an 8.0, La Petite Auberge 7.5, and Joséphine Chez Dumonet 7.0. Of course, the gourmet economist scored these restaurants thirty-eight years ago. Chefs have since come and gone, neighborhoods changed then changed again, and Paris is a highly competitive market for fine dining. Perhaps it is remarkable that these six remain and did not disappoint when we came calling. Au contraire, each restaurant was appetizing and a joy to visit both in its own right and as part of a culinary quest to follow in Bela Balassa’s footsteps

As I mentioned at the beginning, Judy and I have some experience with French cuisine, however we are not French cuisine experts. Nevertheless, we had our favorites and, for what it’s worth, we couldn’t help but give our own “grades” to these six restaurants. Using Bela’s grading scale, and for all the reasons stated above in the restaurant reviews, we echo his rating of (Le) Divellec at the top with a 9.0 grade. We’d then grade Le Récamier and Benoit with 8.5 each. L’Ami Louis comes next at 8.0. Last but not least, Josephine Chez Dumonet and La Petite Auberge, we note each at 7.5 while considering them favorite “French comfort food” locations.

Paying homage to Bela Belassa

Our Paris dining project started as an homage to a world class economist. However, the adventure of following his dining recommendations evolved into a captivating culinary quest. Bela Balassa is deservedly remembered for his significant contributions to our understanding of how international trade functions. He should further be honored, as I do here, as man who knew that sometimes you have to stop worrying about understanding the wider world and simply enjoy a good meal, with good table companions, and within budget… in Paris.

© 2023, Richard Fritz. First published on France Revisited.

This is a splendid article with an interestingly different angle from the usual fare. So nice the author resurrected the fascinating concept of dining utility of a gentleman long departed. Francophiles like me who are careful about their money really appreciate this point of view.

Thank you for this delightful article. I thoroughly enjoyed your concept, greatly admired your advance preparations and envied your gustatory adventures. Wish we could have joined you for lunch one day. Jeanie and Fred