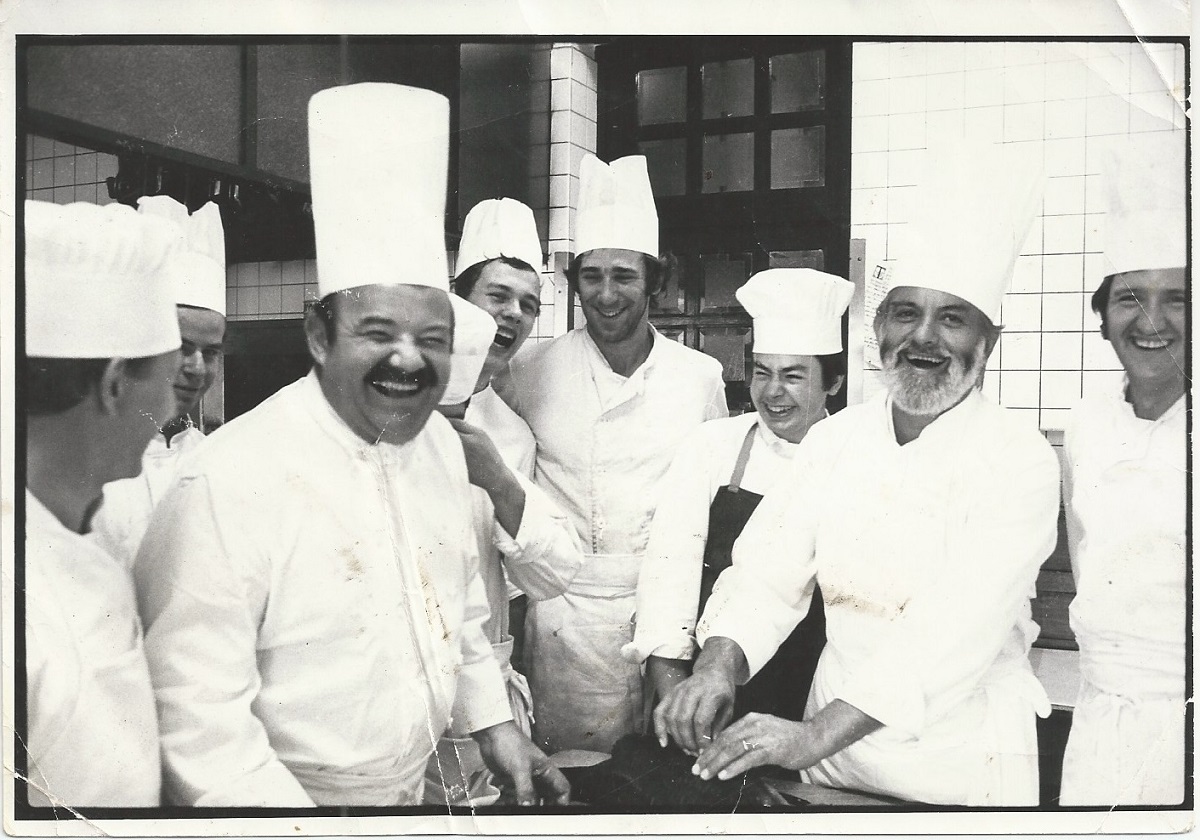

Photo above: Chefs and apprentices in the kitchen at Troisgros in 1976, including Pierre Troisgros (with mustache), Jean Troisgros (with beard) and David Glass (the tall young man in the center).

In 1974, David Glass went to France to study art history but no sooner had he arrived than his interest forked off into the heart of modern French gastronomy. In place of an education at the Sorbonne and the Louvre, he entered into yearlong apprenticeships at two three-star Michelin restaurants that were leading the movement of Nouvelle Cuisine: first with Alain Senderens at l’Archestrate in Paris, then with Jean and Pierre Troisgros at Troisgros in Roanne, 56 miles northwest of Lyon. Upon his return to the United States, David started a catering business in Connecticut based on nouvelle cuisine, but it was a recipe for chocolate truffle cake that he had learned in France that would bring him culinary success as he morphed into a master of cakes and chocolates. He now lives in Vermont, where he operates David Glass Chocolates. Forty-five years removed from his culinary and cultural education in France, David pays tribute here to Jean and Pierre Troisgros. Jean passed away in 1983 and Pierre in 2020.

By David Glass

In September 1974, at the age of 26, several days after arriving in Paris to study art history at the Sorbonne, I ate a meal that changed my life. I had made a reservation at l’Archestrate on the recommendation of an acquaintance without knowing what to expect, and little did I know that my first exposure to French gastronomy would take place at a restaurant on the forefront of a type of cuisine that was on its way to conquering the world. Since I didn’t know anyone in Paris, I dined alone that evening. The meal began with a mussel soufflé, followed by sea bass with beurre rouge, tournedos Rossini, an ample selection of the ripest of cheeses, and an ethereal strawberry soufflé. The experience caused me to abandon art history and to devote myself to learning how to cook. I asked Alain Senderens, the chef and owner of l’Archestrate, if I could spend a few days in his kitchen. He said yes. I stayed for a year. (Senderens, who passed away in 2017, had earned his second star in the Michelin guide in 1974 and would receive his third in 1978.)

During my year in Paris, I seized the opportunity to take a road trip with friends to Roanne, a town northwest of Lyon, for a meal at Troisgros. The explosive flavors and exquisite lightness of that meal were the equal of my first encounter with high new gastronomy at l’Archestrate. Immediately I knew where I wanted to spend a second year of apprenticeship.

Thanks to Alain Senderens’ letter of recommendation, I was accepted as an apprentice at Troisgros in 1976. The French dining guide Gault & Millau had named Troisgros the best restaurant in the world in 1968, the same year that it received its third Michelin star. In 1973, the term “nouvelle cuisine” appeared Gault & Millau, referring to a type of cooking whose leaders were Jean and Pierre Troisgros, Alain Senderens, Paul Bocuse, and other chefs. The main tenets of their cooking were lighter sauces, fish that was barely cooked at its center, use of only the freshest ingredients, an emphasis on finding the very best method to cook each ingredient, and using fruits and vegetables that were sourced locally. After a year of developing skills and knowledge with Senderens, I was literally salivating at the prospect of pursuing my culinary education with the Troisgros brothers, while also expanding my sense of France by leaving the capital for a part of the country that few Americans had ever passed through other than those on a long drive toward the Riviera.

The uninformed visitor would never have suspected that a restaurant of Troisgros’s reputation would be found in Roanne. Unceremoniously described as “en face de la gare” (across the street from the train station) in the restaurant’s literature, Troisgros was housed in a building that was less than stunning. Yet I was immediately welcomed with warmth and friendliness as I arrived by train from Paris, and that feeling would remain with me until I left a year later.

I lived in the hotel above the restaurant, so even though I only worked the lunch shift, I was in the building from opening until closing. More than at l’Archestrate, I now had a sense of the full scope of the working day at a restaurant of such caliber. My work day started at 7AM and was over when the last lunch customers set aside their napkins and left, usually around 2PM. As busy and tiring as my own shift was, I could only imagine the extent of the mission of running a restaurant that aimed for 3-star perfection through two full shifts, day in, day out. When I eventually compiled a list of everything that had to get done each day, I felt the true weight of the task. From putting together veal bones, vegetables, herbs and other components of veal stock in the early morning to delivering the final dessert of the evening around 11 PM, the work was non-stop. There was actually no definitive end to the work day. Johnny Hallyday, France’s most famous rocker, dined with friends one evening and stayed until 4 AM.

Staff meals and the 3-star hamburger

Despite the pressure that we all felt to contribute to the Troisgros brothers’ (and Michelin’s) highest standards, there were some truly relaxing moments at the restaurant. Staff meals were a quiet moment between a busy morning of preparation and the hectic lunch or dinner service. For the most part we didn’t eat what was featured on the menu. Instead, I remember eating a lot of beef heart, gratin potatoes, green salads, chicken, less expensive cuts of veal and beef, seasonal vegetables, and occasional sweets. All of us, from the chefs to the apprentices, helped prepare these meals. Since the preparation of the gratin potatoes was part of my job, I would always watch the faces of my fellow cooks and the chefs to see if they liked them. If they didn’t, I was in trouble because this dish was also served to our customers. But they always loved the potatoes. On the other hand, the beef hearts, which were cheap, tough, and definitely not on the menu, were eaten with resigned silence.

We ate our staff meals at a large table in the kitchen, where Jean and Pierre were often joking about something. The rest of us were equally animated, probably as a way to release a final bit of tension before the customers arrived. Sometimes, one of the brothers would discuss the finer points of a particular menu item so that we would understand the reason for preparing a meat or fish a certain way, the combination of ingredients in the sauce, or why the various items on the plate were paired together. I remember a particular discussion about the poached bone marrow that accompanied the giant beef rib in bordelaise sauce and the reason it was included in this dish. We opined on the best way to eat it, with a piece of meat or on a slice of bread with fleur de sel. Since the marrow was served removed from its bone, customers would make the decisions for themselves. (I preferred it with a few grains of salt, letting it melt in my mouth so that it became coated with liquid fat.)

The kitchen staff that year consisted of cooks and apprentices from Holland, Japan, Switzerland, Germany and various regions of France. I was the sole representative of the United States. We took turns leading the preparation for staff meals. When it was their turn, the apprentices from France would typically prepare a dish from their region, thereby introducing us to a cuisine that others, particularly myself and the other foreigners, didn’t know. Everyone was respectful as they tried dishes. Though the French can be snobbish about their country’s or region’s cuisine, at Troisgros, in spite of its fame and notoriety, everybody, from the chefs to the apprentices, appeared interested and fully engaged when sampling a dish that was new to them.

Every once in a while, with no schedule or warning, Jean would issue a proclamation that it was International Day and one of the foreigners among the kitchen staff would be tasked with planning and preparing the staff meal based on his national or regional traditions. In view of all of the various traditions that were presented through the year, I was stumped when it came to planning an all-American meal. My colleagues gave some inappropriate suggestions: pancakes and maple syrup (but there was no Vermont maple syrup available, and who eats pancakes in the afternoon?); fried chicken (I didn’t know how to make fried chicken); hotdogs (NO!!); and a clambake (the ingredients were not available in Roanne). We settled on hamburgers, even though I never ate them and had never cooked one. As unusual as it may sound, the only bite of hamburger I’d ever had in the United States was so grey, so overcooked, and so vile that I spit it into my napkin and threw it away.

Jean had traveled to the United States to give cooking demonstrations, so he knew far more about our cuisine than I did, including about “le hamburger.” When I hesitated, Jean and Pierre immediately took the reins and gave suggestions. First, we were to gather all of the beef scraps. Troisgros’ beef scraps consisted of the “chain” of the filet, which was removed before it was cut into steaks, pieces of the rib steak, and ends of the entrecôte. These were not ordinary cuts that usually comprise a hamburger. Everything was hand-chopped using large knives. Because these were not the fatty cuts of beef normally used to make hamburgers, Pierre added a little kidney fat, and Jean added finely chopped shallots. The burgers were formed thick, so that they wouldn’t overcook. They were covered with cracked peppercorns, like a steak au poivre, and cooked rare. There were no buns, but there was one of the most delicious sauces I have ever tasted: Troisgros’ reduced veal stock, heavy cream and Port. At the first bite, the hamburger was spicy from the peppercorns. Then there was the taste of the rare ground beef, unlike anything ever served in the United States. Because of the high quality of the meat, the hamburger had the flavor of a perfectly cooked steak. The fact that it was ground resulted in more surfaces in the mouth than a slice of steak, and every ground bit exploded with flavor. In another part of the kitchen, one of the cooks made French fries, the French way: twice cooked so that they were crisp on the outside and meltingly soft inside. It was a perfect American meal, re-invented in a Michelin three-star kitchen by two of France’s most famous chefs.

The Apprentice System

The apprentice system in France required young cooks, many starting at the age of 15, to work in a kitchen for two years. They often worked for free or for very little payment, living at home, if they were local, or in a rented apartment or room. My situation was the exception as I was the only one who lived above the restaurant. I received no salary, but my room and board were free. At the end of their apprentice period, the other apprentices would take an exam called the C.A.P. (Certificat d’Aptitude Professionelle), which tested them on everything they learned in the kitchen. Passing this provided a degree that allowed them to advance, so that they could eventually become commis, chef de partie, chef saucier, and eventually chef de cuisine. The younger apprentices were tasked with some of the dirtiest jobs in the restaurant, such as scrubbing grease out the drains or plucking the feathers off huge bags full of frozen thrush. I never drew the worst jobs, probably because I was taller than everyone else and a few years older than the average apprentice.

There was always experimentation going on in the kitchen. Sometimes, the chefs and apprentices were encouraged to contribute ideas. One of my suggestions, a mixture of crumbled fresh goat cheese, finely chopped tomatoes and fresh thyme leaves, shaped into a small dome and presented in a miniature soufflé dish, was added to the amuses gueules (hors d’oeuvres) for a brief time. At the suggestion of a Japanese cook, cured salmon eggs were also adopted for a time. Previously, the eggs had always been discarded, and the Troisgros brothers seemed genuinely amazed when they learned the technique and tasted the cured eggs. My Japanese colleague also showed them how to make tempura batter with a fork instead of a whisk. Jean exclaimed, “Did you see how he made that with a fork?” (The French use a whisk for just about every kind of batter they make.) Novel ideas were always swirling around, and the brothers were always snatching them out of our brains.

Basketball

But all was not cuisine and work at Troisgros. Jean, with his impeccably trimmed grey beard adorning his classically handsome face, was quick to joke with clients. He was a tennis player and in superb condition, though he eventually died on the court at the age of 56, in 1983. Pierre sported a black, bristly mustache and was a bit more serious than Jean, though they could be equally raucous with friends. Pierre was also a bit rotund, although he moved just as quickly as Jean, both in the kitchen and on the basketball court.

One of my fondest memories was the weekly basketball game, which we played in a local gym, with Pierre, Jean, and anyone else who wanted to join. There was nothing so exciting as getting out of the kitchen after a stressful lunch service, changing into a tee shirt and shorts, and playing a no-holds barred game of basketball. I had the double advantage of being an American who grew up with the game and being the tallest member of the staff, an advantage that Pierre tried to deny me by unashamedly grabbing me from behind as I was attempting to make a layup. Meanwhile, Andre, the pastry chef and second tallest, was always waving his hands in my face. Rather than teach them some of the finer points of the game and convince Pierre not to cheat, I used my height and weight to knock into everyone on my way to the basket.

Meals in the dining room

Because I wasn’t paid for my work at the restaurant, Jean and Pierre allowed me to eat free of charge several times in the dining room. Among them was a memorable meal with my friend Reiko, a Japanese student I’d met earlier in my stay in France when she was touring the country. She was charming, so I invited her to visit me in Roanne and have a meal at Troisgros.

Consulting with Pierre about the food and Jean about wine, and keeping in mind Reiko’s love of fish, I decided to have an all-fish dinner. Since Troisgros’ menu depended upon what was available at the market that day, or what a local fisherman showed up with, I requested the day’s arrivals: St. Pierre (no relation to Pierre Troisgros and called John Dory in English) and sea bass. We would forego silverware and eat the entire meal with chopsticks. For the wine, Jean suggested a Bienvenue Batard Montrachet, the best white Burgundy I have ever tasted.

There is nothing so exciting as discussing an upcoming meal at a Michelin 3-star restaurant with the chef himself. By this time, I had learned a lot about the finest cuisine in France, and I wanted to make sure that our meal was going to be memorable. Pierre took his time with me, as if he had nothing more important in the world to do, and gave his suggestions. The St. Pierre would be seasoned with salt and pepper and then grilled. The sea bass would be roasted and served with a classic beurre blanc. I mentioned that Reiko was a small girl and that she was used to eating light meals, as was the custom in Japan. A typical French dinner would probably fill her up before she got to the main course. He suggested that all of the other courses would be very small so that she would have no trouble finishing her dinner. I, on the other hand, was welcome to go into the kitchen and make myself a sandwich if I got hungry afterward. (I did eventually have my standard sandwich that night. It was one that I occasionally made at night while everyone but the night watchman was asleep: a few thick slices of ham, gruyere cheese, and slices of tomato on rustic French bread. All traces were cleaned up before I went to bed.)

Toward the end of my year-long apprenticeship, I was given permission to have a final meal in the dining room, free of charge. I ate alone that evening, but I felt as though I were dining with the entire kitchen and wait staff. Jean, Pierre, and I put together a menu of fish and meat with red and white wines to accompany each dish, and the reason I am not listing the courses is because all was rendered moot as I sat down at the table. The maitre d’hotel came over to say that the chef wanted to offer me a wild woodcock (bécasse), which a hunter had just delivered to the restaurant. He actually leaned in and whispered this to me because at that time it was illegal to serve woodcock, an endangered species, at a restaurant. Nevertheless, with its extra-long beak, the bird was readily identifiable to most people in that part of the country. I was instructed not to say anything to anyone, or exclaim how good it was in a loud voice, or suck the brains out of the head unless I was hiding its beak in my hand.

This wasn’t my first woodcock, but it was the best one I had ever tasted. It was cooked, as all game birds should be, à la goutte de sang (approximately medium rare). The flavor was gamy, the flesh was tender, and the internal organs were mashed up with foie gras and spread on a thin slice of baguette. I had a wickedly tasty red Burgundy, chosen for the occasion by Jean Troisgros, that not only complemented the woodcock but also helped make the meal into something greater than the sum of its parts. It doesn’t happen all the time, but every so often, a wine will perfectly complement a dish. So it was with this Burgundy, which tasted as though its tannin had just crossed over the border from astringent to deliciously round, and the game bird, with its array of flavors. They fit together with stunning results. I sat there savoring the dish until the maitre d’hotel reminded me that it was time for the next course.

Troisgros after hours

It was after this last meal that I started visiting the empty restaurant and kitchen at night after the diners and staff had left. I needed only walk from my bedroom above the restaurant and down a staircase to reach the foyer. I felt that I was watching the ghost of the evening service, complete with the cooks preparing the dinners, Gerard, the stolid maitre d’hotel, giving instructions to the waiters, Michel, the chef de cuisine, steady as a rock, sauteing and roasting diverse items as he was, at the same time, making the sauces, Pierre preparing cuts of beef with the precision of a sushi chef, Jean wandering through the dining room with his cedar box full of Cuban cigars, and the customers thoroughly enjoying themselves.

Some of my favorite memories of that year were of hanging out at the bar inside the restaurant with the brothers and some of the Roannais who did business with Troisgros: the cheese affineur, who had invited me into his cellar to show me how he aged each type of cheese, the chocolatier, who taught me his craft (which would eventually become part of my own), the hunter, whose deliveries depended upon which birds or what deer crossed his path, and others. None of them looked like the type of customer you would expect to see in a three-star restaurant. In fact, the bar itself seemed out of place. If you entered the front door of the restaurant and went to the bar, you would think that you had just entered a small, local dive. Customers there were dressed casually, none in suits or ties or fancy dresses. On the other hand, everyone felt welcome, no matter how they dressed, at the bar and in the restaurant. The warmth, compassion and willingness to share made the restaurant an even homier place.

Throughout that year, the brothers, the cooks and apprentices, the waiters, and all of the other employees of Troisgros made up a family of some of the warmest and kindest people in the food industry, a family that was united in making sure every single customer was warmly received, treated with kindness, and fed the best meal of his or her life. There was no snobbery at Troisgros. Everyone felt comfortable there. Upon entering, every customer felt the excitement of knowing that as long as they were at Troisgros, they would be treated as though they were family, too.

This was one of the most exciting years of my life. After two years of experience at two of the most creative restaurants in the world, I was ready to return home in 1977 to start my American career. Along with a wide range of culinary skills, what I especially learned from Jean and Pierre Troisgros was their talent for pleasing staff and customers. They served as my models in that respect as I returned to the U.S. with the ambition of creating my own business.

Jean, as noted earlier, died young, in 1983 at the age of 56. Pierre lived a long life and got to see his son Michel and grandsons take over the business and move Maison Troisgros, their gastronomic restaurant, to a beautiful new location in Ouches, a few miles outside of Roanne. Pierre died in 2020 at the age of 92.

RIP, Jean and Pierre Troisgros. Thank you for teaching me so much about French cuisine—and about so much more.

© 2021, David Glass. First published on France Revisited, francerevisited.com.

See David Glass Chocolates for more about the author.

See Maison Troisgros for more about Troisgros restaurants and lodging.