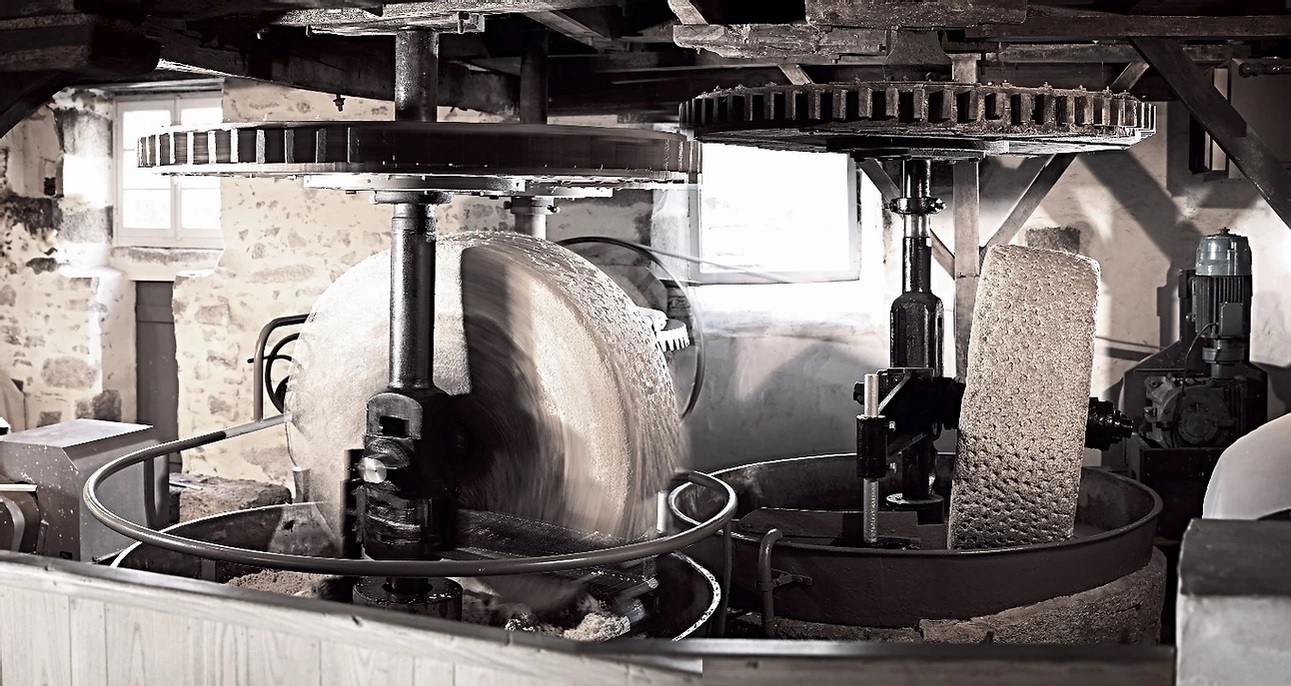

Granite Millstones at the Moulin du Got papermill (c) Moulin du Got

It’s nearly a shame to read Courtney Withrow’s article below on a screen since it concerns the pleasure of paper: seeing it made, touching it, reading on it and admiring artistic work made with or on it. But it’s a good read nonetheless.

The Moulin du Got is a functioning 500-year-old paper mill near the town of Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat, 12 miles east of Limoges. (See part one of this 2-part series for more about the town.). Built at the end of the 15th century and operational since at least 1522, the mill functioned until 1954, when it was no longer commercially viable. After a nearly 50-year slumber, production was revived in 2003, though no longer with the mass market in mind. Instead, using historical processes, the mill, run by a non-profit association, creates a variety of types of paper from cotton, linen, hemp and other materials, particularly for use in graphic arts.

Open to visitors who can follow these processes from start to finish, the Moulin du Got is a wonderful example of a living historical site as it combines an artisanal papermaking factory, a print shop, an exhibition gallery and hands-on programming for all ages.

By Courtney Withrow

Situated two miles from the center of Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat at the confluence of the Tard and Vienne Rivers, surrounded by rolling fields on one side and unspoiled woods on another, the Moulin du Got’s idyllic location has remained unchanged since the mill was constructed here in the late fifteenth century.

This pastoral landscape accentuates the paper mill’s antiquated charm. Harkening back to a bygone era of artisanal and early industrial papermaking and printing, the mill now manufactures paper by hand as well as with nineteenth-century machinery. While the central mission of the Moulin du Got is historical, it presents living history since this is a fully functional papermill employing a team able to create a beautiful variety of artisanal paper for commercial clients and for visitors to the mill.

For all the slowness that the countryside and the methodical, deliberate process of papermaking represent (it can take hours, even days, for sheets of paper to dry), the Moulin du Got is bustling with life. While the paper-making and printing teams work, other artisans and printers act as tour guides. The Moulin du Got carries on its business even as tourists wander throughout its 500-year-old rooms.

History of the Moulin du Got

Moulin means mill, as in the Moulin Rouge, the Red Mill. And Got is a perversion of gué, meaning ford in French, as in the place where this mill was built. Operational on the Tard River in 1522, the Moulin du Got originally housed nine piles with wooden mallets, which would grind up bits of hemp and linen. Hemp and linen are still the primary papermaking materials used in the mill today, in addition to cotton. Got was one of 24 paper mills around Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat during the 18th-century heydays of paper production in the region.

As the demand for paper increased in the 19th century, the Moulin du Got transitioned from using hemp and linen to straw, a more abundant resource in Limousin. The mill also installed a Hollander beater, which allowed for the production of larger quantities of more refined paper, and a paper machine that mechanized the conversion of pulp into sheets of paper. These enabled the doubling of production. By the 1930s, the Moulin du Got was generating 100 tons of paper per year, but larger, more modern production sites were beginning to surpass it. In the mill’s final chapter before its mid-century closure, it manufactured reinforced cardboard, which was used for toys, masks and dolls. But then the arrival of plastic in the mid-20th century diminished its markets for reinforced cardboard.

The Moulin du Got Today

Despite its agility in the shifting paper industry for 400 years, the Moulin du Got closed in 1954. The building sat vacant until 1997, when a non-profit association was founded with the aim of bringing the paper mill and its traditional methods of paper manufacture back to life. Such associations in France typically seek subsidies from local and regional funds to help them achieve their historical-minded goals. In this case, the town of Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat stepped up to the plate to purchase the property, and through various local, regional and even European funding programs, along with perseverance on the part of the association, the Moulin du Got was rehabilitated. After five years of renovation and a training program for a young cohort of paper crafters and printers, the mill reopened in 2003.

Through the various processes used here, the mill now produces about 1.8 tons of paper each year. Electric motors power the paper mill rather than its original water wheels, however, the wheels have been restored and are used for demonstrations.

The Process of Paper Production

Stepping inside the Moulin du Got one sunny Saturday afternoon, I traded the quiet of the Limousin countryside for a flurry of activity. While visitors browsed through handcrafted items in the boutique adjacent to the welcome area, printers were hard at work in the print shop just beyond the boutique, handling cast-iron contraptions that pinged and clicked like slot machines.

The guided tour begins, however, in the heart of the mill where two enormous granite millstones resembling huge wheels of cheese stand atop a bed of ground-up hemp, linen and cotton. As they rotate, the millstones grind the grey, shredded cloth underneath until it looks like dryer lint.

Past the millstones stand large vats filled with pulp. A Hollander beater chops the pulp with metal blades in order to refine it, producing paper with thin fibers. Once the Hollander beater thins the pulp, the mixture is fed through the paper machine. Equipped with several spinning cylinders, the paper machine draws the pulp from its tub and pushes it across its cylinders, flattening it to make long sheets of paper.

The millstones, the Hollander beater and the paper machine represent only one papermaking process at the Moulin du Got. Pre-industrial, handmade techniques are also used. There, the paper crafter fills a rectangular wooden frame with pulp, presses it, then delicately removes the waterlogged sheet and lays it between two pieces of felt to dry. Liquid pulp, resembling watered-down milk, drips off the wooden frame as the crafter works. All of the pulp filling the two large tubs will be transformed into sheets of solid paper, either by hand or by machine.

Beyond Paper Production

While papermaking itself constitutes the most significant part of the Moulin du Got’s mission, a portion of the drying room serves as an exhibition gallery. This year’s exhibition concerns paper artwork inspired by Japanese culture.

The mill also houses a printing shop. Three typography machines from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries allow the printers to create graphic art, lithographs and engravings. The highlight of the printing shop is the enormous linotype machine, which casts lead fragments into typeset blocks of text for individual use. The huge linotype stands taller than an armoire and sits wider than an armchair. When operated it makes an immense racket. The machine uses hot metal typesetting. It contains a reservoir of molten lead, which it transforms into a block of letters when the typist enters a word on the keyboard. The linotype is sustainable, so when the printers are done with a block of text they can put it back into the reservoir of molten lead, melting it down again for reuse.

Although printing wasn’t an original operation of the Moulin du Got, the traditional printing shop was a logical addition to the historical site. In the shop, the printers set their creativity free, fashioning unique bookmarks, notebooks, postcards and other items to sell in the mill’s boutique. Most of the paper and printing produced is sold on-site, however, the mill also fills special orders for artists, editors and other printers.

Using techniques from different eras, the team at Moulin du Got creates a variety of paper types. The thicker paper made by hand, with its denser fibers, is destined for watercolor painting or engravings. From the paper machine, artisans can produce long, fine sheets or ribbed, “smocked” paper. Most of the paper is stiff, with a slight yet noticeable texture. The thick, handmade paper comes out speckled, the denser pulp making for a grainier appearance.

Special Creations

In the years since its reopening, the Moulin du Got has received accolades for its commitment to historical craftsmanship and pthe reservation of cultural heritage. A schedule of programs that are open to the public at the mill include marionette shows, origami lessons and classes in postcard design and Japanese-style painting. In 2009, the site’s educational, cultural and artistic mission won the Moulin du Got a first-place prize in the national Rubans de Patrimoine competition, which gives financial awards to heritage-minded initiatives throughout France.

This is living heritage since the team continues to experiment with new initiatives and to fulfill specialized requests from clients. They’ll sometimes manufacture paper from unexpected materials such as vegetables or blue jeans. For one of their clients, a winegrower, the team created paper wine bottle labels made from grape stems. Moulin du Got paper has also been used in the design of artisanal lampshades. Visiting artists-in-residence pursue creative projects, such as the author who published his book entirely by hand, page by page, with the help of the mill’s artisans and printers.

The Moulin du Got may be well off the beaten path, but once arrived visitors are drawn into the craftsmanship and physicality of paper, printing and typography, and perhaps to the pleasure of holding and reading a book rather than a screen.

Le Moulin du Got, 87400 Saint-Léonard-du-Noblat. Tel. 05 55 57 18 74.

Photo: From the Moulin du Got boutique. The cover of the purple notepad is an example of “smocked” paper and the bookmark is fashioned from paper made by hand. Photo: Courtney Withrow

© 2020, Courtney Withrow for France Revisited

Courtney Withrow is a freelance writer living in Brussels, Belgium. During her nine-month stay in Limoges as a teaching assistant, she visited several small towns in Haute-Vienne, including Saint-Leonard-de-Noblat. She maintains a travel blog.

Visiting Preserved and Restored Mills Throughout France

Hundreds of preserved and restored mills of all kinds can be visited or viewed by travelers in France. Some have been restored to function in a way related to their original use, as at the Moulin du Got, while others live on as exhibition centers, restaurants or B&Bs. Travelers particularly interested in mills should check out the website of the FFAM, Fédération Française des Associations de sauvegarde des Moulins, the French Federation of Associations for the Preservations of Mills. The FFAM’s website provides links to the websites of non-profit associations throughout the country and a map indicating the location of hundreds of preserved mills, whether preserved for non-profit, for profit or private use. Some may be visited year-round and many more in summer and during school vacations. Special visits are organized at mills throughout France during Mill Days (Journées du Moulins), held over the fourth weekend of June.

– GLK

Return to part one of this 2-part series, Saint Leonard de Noblat: Pilgrims, prisoners, pastries, porcelain, papermill.

What an interesting article! It is terrific to see genuine rebirth of the past for a new era.

Very interesting and not far off our route to or from our daughter’s. I’d like to take the detour and visit. I missed open hours in the information given.

Opening times are irregular for a site such as this, particularly since they depend on having guides available. Here’s what the Moulin du Got has posted for this summer: https://www.moulindugot.com/copie-de-exposition .