Photo above: Innocents abroad: Elizabeth and Michael Esris at Versailles in 1971. © Michael Esris.

Photographs from nearly half a century ago lead Elizabeth Esris to revisit her first encounter with Paris with her then-boyfriend (now husband) and to rejoice in the timeless nature of travel discovery.

* * *

During lockdown I can travel virtually anywhere with a few clicks: to a book club in Pennsylvania, to an aperitif with friends in France, to an opera at the Met, to exercise with Olympic athletes, to meditate with Oprah. But I miss real travel and find myself journeying through memory as I spot mementoes around the house.

Two such souvenirs remind me of my first trip to Paris when I was 21, in 1971. With backpack and boyfriend—later my husband—I had set out on a “grand tour” of Europe.

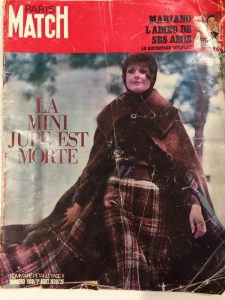

Reaching up to a high shelf in a closet, I find a cherished copy of “Paris Match” that I had bought in Center City Philadelphia in August 1970. The tattered cover proclaims, “La Mini-Jupe est Morte” and foretells of radical changes dictated by the capital of fashion. From the mid-60s to that summer, mini skirts were de rigueur for young women. I remember being angry at the thought that mini-skirts, emblematic of the freedom, defiance and promise of my generation, could be so easily dismissed. But when I went to Paris the following summer, I saw calf-length skirts that I would soon be wearing and long, knit triangular shawls that draped the shoulder and reached down the back to the sandaled feet of beautiful Parisians. For me, it was the most romantic look I had ever seen. When I came home, my grandmother made a long shawl for me, and I wore it in the fall with my peasant skirts like an acclamation for haute couture on my college campus.

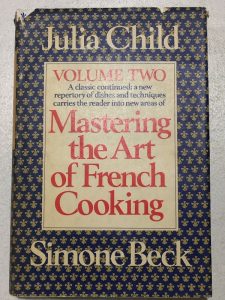

The “Paris Match” further reminds me of the worn copy of Julie Child and Simone Beck’s, Mastering the Art of French Cooking tucked between the French cookbooks in my kitchen. I purchased it when I returned from Paris that summer. I was determined to make croissants for my family, to amaze them by baking the most delicious pastry I had ever tasted. After twelve hours and endless handfuls of butter, I produced a cracker-thin crescent that brought me to tears. Still, I smile when I recall it and realize that my journey to Paris was more than a visit to monuments and literary mystique; Paris infused me with an urgency to make it part of my identity.

The “Paris Match” further reminds me of the worn copy of Julie Child and Simone Beck’s, Mastering the Art of French Cooking tucked between the French cookbooks in my kitchen. I purchased it when I returned from Paris that summer. I was determined to make croissants for my family, to amaze them by baking the most delicious pastry I had ever tasted. After twelve hours and endless handfuls of butter, I produced a cracker-thin crescent that brought me to tears. Still, I smile when I recall it and realize that my journey to Paris was more than a visit to monuments and literary mystique; Paris infused me with an urgency to make it part of my identity.

When I met Mike in college I confided in him a resolve that had been with me since devouring Flaubert, Fitzgerald, Balzac and Hemingway and being introduced to Edith Piaf and Jacques Brel in Madame Cooperstein’s French 1 class: I was going to explore Europe and see Paris while I was young, no matter what. I was leaving at the end of the spring semester with or without him.

By June we had a copy of Arthur Frommer’s Europe on 5 Dollars a Day, Eurail Passes and our paltry savings from after school jobs along with his Bar Mitzvah stash. We planned that the final stops on our travels would be the South of France and finally Paris. Paris was to be savored and left to steep within us for the flight home and beyond.

Mike and I purchased backpacks that are unrecognizable in today’s wilderness outfitted world. They had bulky, exterior aluminum frames onto which was strapped a thick nylon bag. As we crossed borders from West Germany to Poland and back into the free world on our summer journey, we bought and sewed patches on our packs to declare our wanderings. They hang in our basement today as mementoes of two travelers landing in Frankfurt so naïve that we didn’t know to exchange dollars for Deutsche Marks before trying to pay a bus fare.

Preparations for the trip also led us to buy matching pairs of the first true athletic shoes we had ever seen—Adidas. They were made of white leather with three distinctive black stripes and had a sturdy, supportive construction unlike the relaxed canvas sneakers we had worn since childhood; we were confident that our feet would survive the extensive walking we anticipated. Adidas were new to us, but they were sensations in Eastern Europe where people stopped us to see the shoes up close and to ask how Mike could have cut his jeans to make shorts. Levi’s and Lee’s and Wrangler jeans were highly prized by young Europeans who were fascinated by everything American.

We finally reached Paris after more than six weeks of travel, arriving at Gare de Lyon on a night train from Nice, a diesel that lumbered on for 12 hours and clanged into the station. We were tired and anxious to reach the pension we had selected from our guidebook. With map in hand we walked across the Seine on Pont d’Austerlitz and followed the Quai. Our eyes were drawn to the river, to Notre Dame, and the bouquinistes on the Quai de la Tournelle, but what imprinted itself upon me was the fountain at Place Saint-Michel as we turned left to head toward rue Saint André des Arts. Place Saint-Michel and the fountain were alive with young people—meeting, reading, embracing, walking, and looking like the literate, involved intellectuals that I had imagined. My literary passions may well have played a part in my perspective.

We were headed to Pension Eugénie on rue St. André des Arts, described in Frommer’s as offering cheap but decent room and board in the heart of the Left Bank, near to literary shrines that I wanted to visit. We booked a room for ten days with a shared hallway bath and WC for 8 Francs a night—about $2.50. The room was a tiny space that must have once been part of a bathroom; there was a defunct bidet about a foot from our bed. We had never seen one nor did we know how it worked. Other friends who traveled in those days said they used bidets to wash their jeans.

Our room had large windows that overlooked the noisy street. On most nights we watched a group of Hare Krishnas who chanted and smiled up at us. The most wonderful thing about Pension Eugénie was the breakfast of a large croissant with butter and preserves and delicious café au lait—included in the price—delivered to our door each day. We were cramped as we sat on the bed and bidet to eat, but we could not imagine more beautiful mornings. Years later, as parents with kids in college, we returned to the street to find a refurbished Hotel Eugénie offering rooms for over 100 Euros—breakfast not included. (It is now up to about 300 euros a night!)

Today, I’ve set up our old slide projector to match my memories with images. As the slides click by, I see all the tourist stops: views from the top of la Tour Eiffel, Sacré Coeur, and Notre-Dame; the Louvre without the Pyramid; Jeu de Paume and the Impressionists before Musée d’Orsay became a reality; Napoleon’s Tomb, Versailles, Samaritaine; and the obligatory stops at 27 rue de Fleurus, where Gertrude Stein lived with Alice B. Toklas, and La Closerie des Lilas, where Hemingway regularly drank and wrote at one of its marble-topped tables. We certainly could not afford a meal at La Closerie or any of Hemingway’s haunts, so there are no restaurants to note, but I remember savoring steak frites in unnamed cafes and vin rouge ordinaire that Frommer’s taught us to order. Like Hemingway, I had given the address of The American Express at 11 rue Scribe to family and friends as a point of contact. On the morning after our arrival we made our way there, marveled at the Paris Opéra and picked up mail feeling like heirs to The Lost Generation.

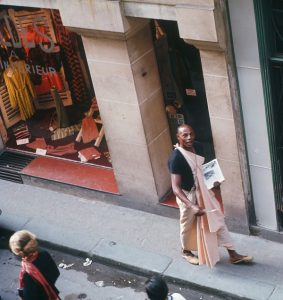

In the photos, structures in Paris appear grayer than today, with soot marring limestone walls or outlining sculptures such as those on the Arc de Triomphe. I am surprised by how light traffic seems to be in my pictures. There are many photos from both day and night where the streets seem quiet compared to the congestion and speed of Paris that I’ve witnessed on subsequent trips. Most cars in the pictures are small and boxy except for the occasional elongated Citroen or dilapidated VW bus, and I recall the many scooters and Solex mopeds that navigated streets and, occasionally, sidewalks.

Visible in all our slides are reminders of the endless walking we did in the summer of 1971 and the places we stumbled upon. Historic Les Halles, the legendary food market, had recently been torn down, but we would visit the Flower Market on Île de la Cité mentioned in Frommer’s—or so we thought. We were surprised when we arrived and found what looked and sounded like a jungle; we did not know that on Sundays it became the Bird Market. Walking through row after row of colorful birds in cages, in cars, and in the hands of those who came to buy, we reveled in exotic bird calls as well as the more familiar sounds of chickens. But it was the enthusiastic pedestrians who were drawn to them that captivated us. This was not the scene of a reluctant parent taking a child to buy a pet; it was a dynamic venue that existed because so many people delighted in birds of all kinds.

Birds intrigued us again when we walked to the Jardin des Tuileries and saw a gentleman in a dark suit feeding groups of frenetic birds and then enticing them to perch on him. Among the birds were pigeons and sparrows. Passersby were interested and a few stopped to chat, but they did not surround him as if he were an oddity. Years later we read that he was part of a long tradition of Tuileries Garden Bird Charmers, as they were called, with roots that date back to the 19th century. The original bird charmers were street performers who had been featured in French, British and American periodicals, including Scientific American in 1885. Whether this gentleman regarded himself as a performer or as someone who simply loved birds, we did not know; to us he was yet another wonder in a city that surprised with every turn of a corner.

In 1971, the Eiffel Tower did not sparkle with twinkling lights; rather, it was illuminated with a dramatic amber glow. Still, the image I see in my slides is as iconic as the bridges, the boulevards, and the churches. Without the intrusion of dated cars or clothing styles on pedestrians in photos, Paris’s beloved landmarks are timeless.

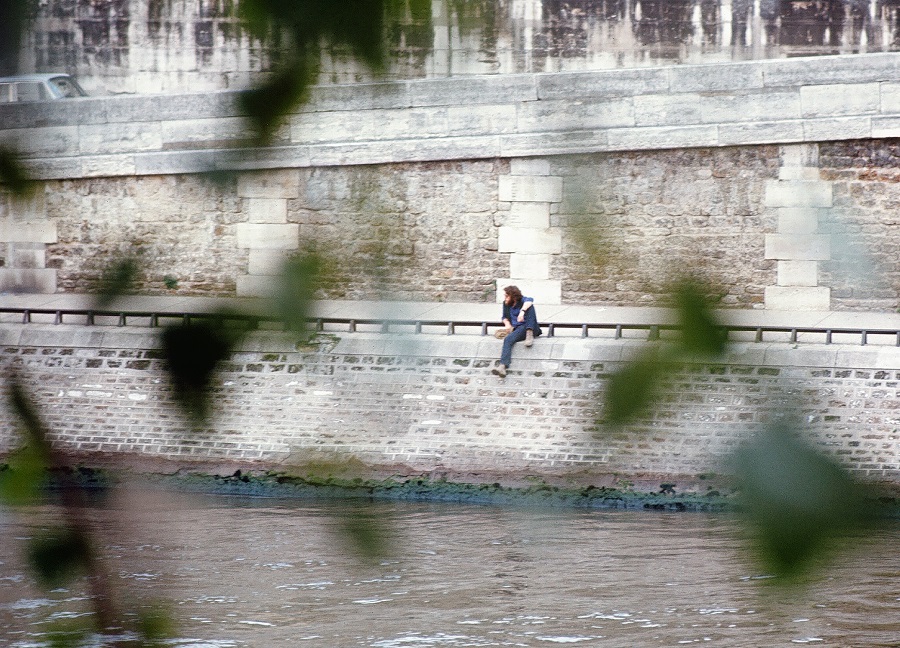

Among my favorite pictures is a long shot of a man in jeans sitting on the bank of the Seine. One leg hangs over the wall, the other is pulled up to his chest. This young man, my peer, depicts so much of what I find compelling about Paris. He seems at ease and thoughtful. His moment of intimacy with the river is natural. Surrounded by history and beauty but not constrained by it, he is part of a complex city that endures as well as changes. His sanguine presence, like that of the old bird charmer, suggests that Paris embraces the individual as vital to its identity.

My afternoon immersed in Paris 1971 includes the predictable nostalgia for youth and life about to unfold. It also validates my belief that Paris is alive and changeable yet cultivates a dignified permanence that seduced me then as it does today. In my adolescence I was drawn to Paris by literature. My first visit fulfilled my girlhood aspirations as reader and dreamer but also left me wanting to learn more about its history, read more of its literature, cook its food, find streets not in guidebooks, and visit again and again. My first trip to Paris ensnared me and I have been a willing captive ever since. This vicarious journey during quarantine allows me to savor the decaying pages of a 50-year-old “Paris Match” and look forward to my next moment on the banks of the Seine.

Text © 2020, Elizabeth Esris.

Photos © 1971, Michael Esris. (Photos taken with a Pentax Spotmatic.)

More of Elizabeth Esris’s illustrated personal essays about travel in France can be found here.

Readers interested in contributing an illustrated personal essay about their own long-ago travel experiences are invited to write to the editor at gary [at] francerevisited.com.

What a lovely account of this first Paris visit! It brought so many memories!

My first visit was in 1971 as well! I especially like your memory of the bidet used for washing jeans…

I so enjoyed reading all about your travels to France. I relived a bit of my own excitement from when I visited Paris as a college student in 1969. It came as part of an European tour of five countries hosted by a professor as an optional field for his Anthropology class I had just completed. From then on I dreamt of the time when I’d be able to do more. It led to my love of travel that I began again years later upon my retirement. I’m looking forward to when we can resume exploring the world once again.

It is wonderful how memories from the past can be so vibrant when we immerse ourselves in them. Visits as students–like yours and mine–stay with us always.

Elizabeth,

Mille fois merci! Your article brings back wonderful memories of my year as an “au pair” and student in Paris from July 1967-June 1968. You have described the unique soul of the city.

During my sejour, I participated in the events of the student initiated riots (les jours noirs de mai “68”) and marched arm in arm with french students. Up close and personal. Until that time it was difficult to create a friendship with the French; I was told the French were essentially chauvinistic. Fortunately, I worked for a wonderful family. I still connect with my young charge after over 50 years. Since that time, I have returned to Paris at every opportunity. Having mastered the art of the flaneur, Paris never disappoints. There are always new areas to be explored and discoveries to be made. Thank you again for bringing a smile to my face. Vive La France!

Diane,

What an incredible year for you to live in Paris as a young woman. Thanks for your comments and for allowing me to glimpse your “arm and arm” moment with history!

Hemingway was right, wasn’t he?

Elizabeth