I’m of two minds when it comes to travel writing, the mind that wants to travel and the mind that wants to write. It takes a cordial understanding between the two to get any work done during coronavirus lockdown.

So I’m pleased, upon my return from a masked excursion to the bakery and the cheese shop this afternoon, to find that the two agree to sit together to work on a new travel article. At my desk I hop onto the first train out of Paris, and I write:

Thirty minutes after setting out southeast from Paris by train, you’ll notice the flat landscape begin to flutter. Then swells form. And when those swells rise to hills—hills covered with colza, wheat and barley and crowned with woods, cattle grazing down below—that’s when you know that you’ve entered Burgundy.

But what’s my destination? Why head toward hills in the first place?

Before sitting at my desk I opened the refrigerator for some butter to spread on the warm baguette I’d just bought. Among the old photographs magneted to the refrigerator door is one taken in the backyard of the home where I grew up. It shows the hill that my siblings and I would roll down in summer and sled down in winter. Maybe that’s why I like rolling hills—they make me want to explore, yet their tranquil flow across the landscapes reassures me that I can find my way home. “Hill” is what we called the slight gradient in our backyard as children, though anyone over the age of seven would see instead a small slope to a row of trees on the edge of the property. On the opposite side of the trees lived a girl who was in my class. She was a volatile girl. Her name was…

Before sitting at my desk I opened the refrigerator for some butter to spread on the warm baguette I’d just bought. Among the old photographs magneted to the refrigerator door is one taken in the backyard of the home where I grew up. It shows the hill that my siblings and I would roll down in summer and sled down in winter. Maybe that’s why I like rolling hills—they make me want to explore, yet their tranquil flow across the landscapes reassures me that I can find my way home. “Hill” is what we called the slight gradient in our backyard as children, though anyone over the age of seven would see instead a small slope to a row of trees on the edge of the property. On the opposite side of the trees lived a girl who was in my class. She was a volatile girl. Her name was…

Stop! The traveling mind, the one that resists confinement, won’t cooperate. That mind is quick to switch tracks to examine an old photograph or to look out the window or to give me a sudden urge to go running. That’s the mind that rattles around looking for exits. While my inward traveling mind tries to focus on the task at hand, my outward traveling mind is looking for the name of the girl next door from second grade. It’s telling me to call my sister to see if she remembers. It’s suggesting that I ask another neighbor from my childhood with whom I recently connected on Facebook.

No! Facebook is the death of cordial understanding. Don’t do it! Focus, demands the other mind, the one that’s satisfied sitting at the desk, riding a train to Burgundy. I reread my opening line hoping that its momentum will project me onward.

Thirty minutes after setting out southeast from Paris by train, you’ll notice the flat landscape begin to flutter. Then swells form. And when those swells rise to hills—hills covered with colza, wheat and barley and crowned with woods, cattle grazing down below—that’s when you know that you’ve entered Burgundy.

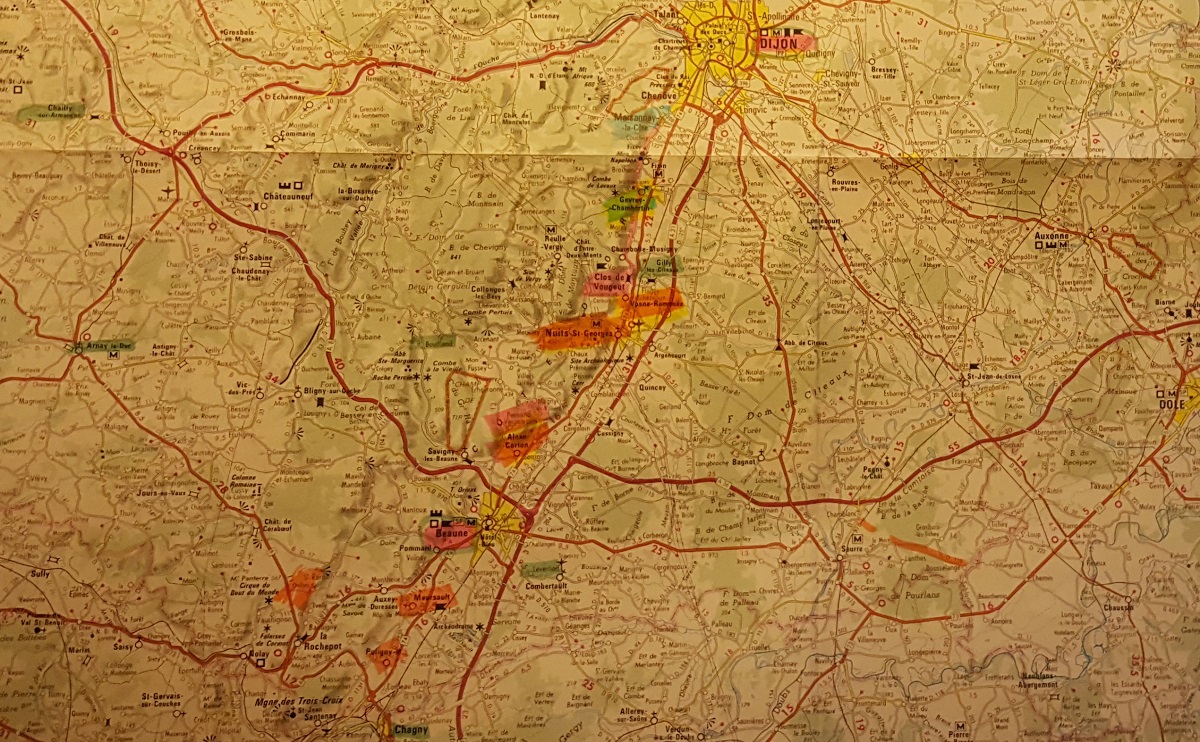

I unfold a map of Burgundy. On the train to where exactly?

But the outward traveling mind, averse to being bridled by lockdown, won’t let me study the map. I sense it rummaging around in nearly forgotten corners of my brain, unwilling to stay on the tracks to Burgundy, looking to latch onto anything that will pull me away from my text. Forget the girl then, let’s look for something else, it seems to say. And then it stumbles upon something, an open door. It elbows the mind that’s examining the map to let it know that it has found an exit.

It has found, or remembered, the existence of my storage space in the basement, my cave. Simultaneously both minds, the one that accepts confinement and the one that resists, come to the new cordial understanding that my sense of personal space can now be extended by a few square meters if I were to go down to the basement. I feel a shiver of liberation at the thought of visiting my cave in the cellar without having to justify myself to anyone. I haven’t been down there in several years. The train to Burgundy grounds to a halt, in the middle of nowhere.

The last time I went down to my storage space in the cellar was right after a team of thieves broke into it three or four years ago. They busted the padlocks on many of the storage spaces and stole all the wine. Well, they stole my wine, about three cases of it. I don’t know what they took from others because there are few direct exchanges between neighbors in this building other than to say “bonjour” or some expression of embarrassment when we cross paths at the entrance or in the winding staircase. My neighbors were social distancing before it became a health necessity. And when it did, many distanced themselves even further by fleeing Paris for the countryside or the coast in the illusion that, far from our building, far from Paris, lay true freedom, and by their exodus they could deny their confinement and negate their fears, as though, given a deadline to hole up, they’d suddenly realized that they’d been prisoners in Paris for so very long and needed to run while the guards weren’t looking, only to make themselves prisoners elsewhere.

I should thank them their intended escape. Now we don’t have to apologize for checking the mail or throwing out the garbage at the same time. Pardon, pardon, excusez-moi. Après vous, monsieur, madame. Fewer hands on the railings, the light switches and the door handles. No overflow of the trash bins by the end of the weekend. And the greatest gift of their absence: the silence. No footsteps from above, no crying baby from below, no barking dog, no arguing couple, no Airbnbers dragging their luggage up the stairs. No one to judge. Freedom. I wonder if this is what it would feel like to be the only person left alive.

I should thank them their intended escape. Now we don’t have to apologize for checking the mail or throwing out the garbage at the same time. Pardon, pardon, excusez-moi. Après vous, monsieur, madame. Fewer hands on the railings, the light switches and the door handles. No overflow of the trash bins by the end of the weekend. And the greatest gift of their absence: the silence. No footsteps from above, no crying baby from below, no barking dog, no arguing couple, no Airbnbers dragging their luggage up the stairs. No one to judge. Freedom. I wonder if this is what it would feel like to be the only person left alive.

No, there’s my 82-year-old neighbor, she’s still here. She’s the only neighbor with whom I have an actual conversation about anything other than a problem in the building. When they first announced corona confinement, I asked if she planned on going anywhere to ride it out. Her reply: “The last time I went away to ride something out was when I was 6 years old, after they rounded up my father, and my mother sent me to live in the Alps with a family I didn’t know—that’s enough for me.” I told her that if she ever needed anything and didn’t want to go out, I could get groceries for her. “Oh, I’m going out,” she said. “They stole my childhood, no one’s going to steal my old age.”

So I’m not going to complain that someone stole a few dozen bottles of wine that I had in my storage space, my cave. It wasn’t exceptional wine anyway. The temperature and the humidity level in the basement are ideal for wine, but I’m not one to buy bottles with the intention of letting tannins or acidity age gracefully in the dark. I’m not a collector.

I buy a few bottles here and there when I travel to wine regions in France, and winegrowers and tourist officials sometimes give me a bottle or two. Other than a bottle of champagne awaiting an occasion in the refrigerator, I keep bottles on a shelf in the kitchen. I’ll open one or two when I have guests over or take one to someone’s home when I’m invited. But I tend to receive and buy more than I use, so when two kitchen shelves were full I began putting the overflow into the basement.

After the theft I stopped taking bottles down there. I bought two wine stands that hold a dozen bottles each and placed them in the corner of the kitchen.

When not quarantined, I drink wine often, socially. But I don’t drink wine when I’m at home alone. I like sharing wine and the effects of wine. Drinking by myself does nothing for me other than make me want to have someone with whom to share the drink. So I haven’t been drinking wine during lockdown, just the occasional whiskey, calvados, cognac or rum late at night. “A little schnaaps,” as my Great-Aunt Helen would call her nightcap. She lived with us toward the end. “Don’t be stingy,” she’d say when she’d ask us to pour her a tumbler before going to bed. I told that to my friend Guillaume and he now repeats it when he comes over for a drink—he did before lockdown. For religious reasons my friend Achmed says that he doesn’t drink. However, since he isn’t religious, he sometimes will. But it’s Ramadan now, so he won’t.

As I’m thinking about my friends, I sense my resisting, exit-seeking mind standing there with its arms cross waiting for me to remember that it had found me a novel excursion: The cellar, it says, let’s go see what’s down there.

I put on my shoes and grab a flashlight. Work began in the stairwell shortly before lockdown, and with it paused the building feels like an abandoned construction site. Half the lights don’t work. The courtyard door doesn’t shut. Common pigeons are gathering near the garbage bins, as though plotting to take over. On the way to the bakery and the cheese shop earlier today I observed on the cobblestones the courting rituals of pigeons, which reminded me that I’ve forgotten my own. I watched wood pigeons feeding on the budding plane trees, beneath which their beige droppings are distinguishable from the white of their pedestrian cousins. Last night, when I went out for a walk, I saw a couple of ducks waddling across the street without looking either way. And I watched a group of rats playing 3-on-3 basketball around a trash bin. Couldn’t tell which side was winning. I guess they don’t keep score like we do. But living rats is a good sign, because dying rats means that the bubonic plague is here. So vive les rats! Just not so many.

As I suspected, the overhead light isn’t working in the basement. I turn on my flashlight. My storage space is at the end of the corridor—to the left, I remember, number 7. My broken padlock still lies on the ground. I never replaced it. Why bother? I don’t even remember what I ever used this storage space for.

I pull open the door and am reminded: There’s a bicycle in need of repair that I bought during the transportation strike of 1995; wobbly chairs from my previous apartment; a mattress wrapped in a tarp; a broken suitcase that I kept, thinking that I might use it if ever I moved again; the computer box from about 3 laptops ago—the one on which I was going to write a new guidebook. There they were: memories. There it was: junk. Memorable junk… Junk memories. My cave. My additional space. Could my outward traveling, resisting, exit-seeking mind do no better than to send me here? Instead of opening wings, all this journey to the basement has brought me is the promise of things long gone. But there’s no courage in nostalgia, only in throwing things away.

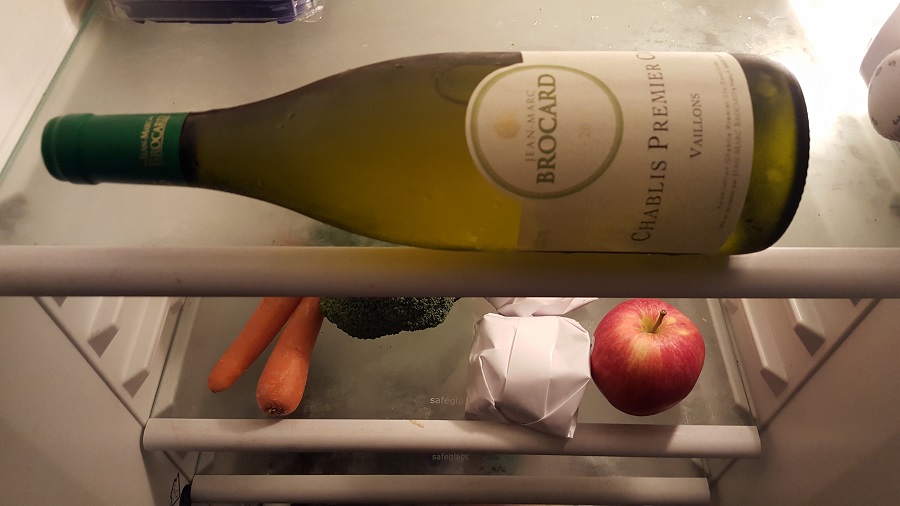

Then I see it: Near the ground there’s a bottle of wine that the thieves missed, or didn’t want. I dust it off and shine the light on it. Chablis premier cru, Vaillons, 2011, Domaine Jean-Marc Brocard.

Just then I hear a sound that seems to say, “Do it now… Do it now.”

I call out, “Hello?”

“Do it now. Do it now.”

“Is someone there? Il y a quelqu’un?”

“Do it now. Do it now.”

Bottle in hand, I run, stumbling against the wall as I rush up to the ground floor, and I keep running for the next two flights in the dusk of the stairwell. Then I slow down. I must have been frightened by the shadow of my own flashlight and the sounds of rats or pigeons. I laugh to myself—at myself. We all need a good, healthy scare every now and then. Several pigeons look drearily at me from outside the stairwell window, biding their time. I knock at the window but they merely step over a few inches as though they’ve just heard a cough.

As if by magic, the light in the stairwell goes on. Approaching the fourth floor I see that my neighbor has come out of her apartment. She must have turned on the light. She has a shopping bag in her hand. Each of us takes a respectful step back.

“Bonjour Madame,” I say.

“Bonjour Monsieur,” she says. “There aren’t many of us left.”

I don’t know which “us” she’s referring to.

I feel a need to justify being out. I hold up the bottle of wine and say, “I’m returning from the cellar, my cave.”

“To your health, then,” she says.

“To the health of us all,” I says, and doing so gives me idea. “Listen,” I say, “I don’t drink alone so maybe you… I can open the bottle and pour you a glass. You don’t have to drink it right here or with me. We have to keep a social distance, so you close your door and drink your glass whenever you want, but this way we’ll share it, in a sense, that is if you drink wine, I don’t know if you do.”

“That’s kind of you,” she says, without indicating her answer.

“Seriously. Chablis 2011, chardonnay.”

She says, “There’s no rush. It can wait.”

Then she wishes me a good end of the day, goes back inside her apartment, and closes the door as if she only came out to turn the light on for me.

I unlock my own door and go inside. I stand against the door. After a few seconds I hear my neighbor go out. I slip off my shoes. I wash my hands. I rinse off the bottle of wine, dry it and place it in the refrigerator. As I return to my living room / office I’m amused by the coincidence that Chablis is in the northwest corner of Burgundy. The train was somewhere near there before my excursion into the cellar. That’s just the momentum I need to get back on track. I reread my opening lines:

Thirty minutes after setting out southeast from Paris by train, you’ll notice the flat landscape begin to flutter. Then swells form. And when those swells rise to hills—hills covered with colza, wheat and barley and crowned with woods, cattle grazing down below—that’s when you know that you’ve entered Burgundy.

I look at my couch. To write or not to write, that is barely the question, for the answer is clear.

I lie down as though I’ve just unpacked my bags from a journey. I think about where I’ve been: I went down to the cellar because the resisting, exit-seeking mind had leaned against the unlocked door of my storage space; downstairs I heard a voice telling me to “do it now”; on the way back up an 82-year-old Holocaust survivor told me that there was no rush, it could wait.

What “it” could wait? What “it” should be done now?

My outward traveling mind and my inward traveling mind start to volley the question back and forth. Their game lulls me to sleep.

When I awaken the sun has dipped behind the buildings across the street. Early evening. How long was I asleep? Where was the sun before my nap? I fade in and out of consciousness. As a child I dreamed of leaping off the hill beside the house and flying, a silent figure over the neighborhood, defying gravity, a solitary victory over the world. But what now could be sweeter than submitting to gravity? It molds me to the couch. I abandon myself to the snug sensation that nothing matters but the comfort of being embraced by gravity. To nap: the great compromise of prisoners. To rest. Not to stand by the window to subjugate myself to alienation but to lie with myself, fading in and out of consciousness. Conscious just enough to feel this delicious gravity-induced satisfaction before sinking back out. Desiring nothing but this warm peace as the sun fades behind the opposite roof. Newtonian satisfaction: the nap: a timeless moment of gravity and of peace. Nothing else matters.

Nothing—but the stomach doesn’t know that. I’m hungry. I sit up. A wide yawn clears my head.

I go to the refrigerator. As I open it, I hear again what I heard in the basement: “Do it now. Do it now.” Immediately, I close it the refrigerator. I see the hill of my childhood home on the door. On the window railing a pigeon with his feather’s puffed is trying to seduce a female: who-rrou, who-rou. Slowly, I open the door again. “Do it now. Do it now.” I know that it’s the sound of the pigeon that I hear, still, the bottle of Chablis seems to be speaking to me. I take it out. “I need to be drunk, now,” it seems to say.

The bottle is telling me that, not me. I do not need to be drunk, and I do not want to be drunk. I want to be lucid as I follow this bottle wherever it will now lead me.

I set on the table the baguette and the cheese that I bought earlier. Two cheeses: a hard goat cheese from Maconnais, on the southern edge of Burgundy, and a soft goat cheese from Tarn, in southwest France.

I open the bottle of wine. I pour myself a glass. Unaccustomed to doing so alone, I imagine that I’m at a wine tasting, better yet a wine pairing.

I hold the glass up to the light, and to my surprise I now see myself driving from Paris to Chablis, in the northwest corner of Burgundy.

I swirl the wine. And I see a chapel surrounded by vineyard.

I inhale the wine. And I see ripe chardonnay grapes on the vines.

I take a mouthful, aerate it and swallow. I see a harvest underway.

Now I remember: I bought this bottle at the Jean-Marc Brocard vineyard during harvest time one September day several years ago. I was with a friend, though I can’t see his face. How strange. You’d think that, confined, you’d remember people, but for the most part you don’t. Your memory is vaguely peopled with people, but they’re ghosts with no distinguishing features, as least as far as the non-essential people are concerned. But who are the essential people? Maybe there are none—all ghosts? What more do I need or want than what I have right here? A nap, a baguette, cheese, a bottle of wine.

The streetlights have come on. The sky is twilight blue, the half-moon waxing or waning, I don’t know which.

The streetlights have come on. The sky is twilight blue, the half-moon waxing or waning, I don’t know which.

I examine the bottle’s label: 2011. I remember visiting Burgundy that year. After the harvest, early autumn, when the grapes in this bottle were little more than juice. I wasn’t in Chablis that time, but further south, in the heart of the Burgundy winegrowing region, the Côte de Beaune and Côte de Nuits growing area.

I pour myself another glass. I try it with the bread and cheese. A fine pairing, especially with the softer goat.

Burgundy. 2011. October. I’d taken the train to Beaune. I was picked up by a Jaguar, a Jag-u-ar, as the driver called it, a deep green Jag-u-ar. Yes, there was a driver, a woman, from company that gives tours in vintage cars. There were two passengers in the back, unknown to me now.

I get the Burgundy map from my desk and spread it on the table. The names of some villages on the map are highlighted in several colors, indicating different trips that I’d taken to the region: Pernard-Vergelesse, Chassagne-Montrachet, Puligny-Montrachet, Gevrey-Chambertin, Aloxe-Corton, Meursault, Marsannay, Orches, Nuit-Saint-Georges.

Bread, cheese, wine, and I now see myself standing by the entrance of Clos de Vougeot, the former abbey that’s now headquarters of the Confrérie des Chevaliers du Tastevin, the international wine order whose members vow to honor and spread the wine gospel of Burgundy. I stand looking at the abbey-chateau surrounded by vineyards, as though it were a promise land, and dreaming of one day being ritually inducted into the order by men in red and gold robes. Maybe that was from yet another trip, or another dream. It’s not easy to recall things past when your main struggle is projecting yourself into the future.

Wine, bread, cheese, wine.

In October 2011 I was in Burgundy. There was a driver, a woman, and two spectral passengers in the backseat of the Jag-u-ar. We drove into the vineyards. We tasted wines. In the evening I attended my first paulée. P-A-U-L-E accent aigu-E. Paulée, pronounced with a sharp “ay” at the end. But at times like this we revert back to our mother tongue, so I relax my throat, unsharpen the é, and dictate into my phone:

In 2011, in October, in Burgundy, I went to a paulee. A paulee is the opposite of social distancing. It’s bacchanalian, as in Bacchus, the Roman god of wine. Traditionally, it was a celebration in Burgundy when a winegrower would honor the back-breaking work of his grape pickers by bringing out and sharing his wine with them to celebrate the end of the grape harvest. The tradition fell by the wayside with the decimation of the vineyards toward the end of the 19th century and was revived in the 1920s, after the First World War and the Influenza Pandemic known as the Spanish Flu had killed countless millions of people around the world. The best known paulee soon became and still is the Paulée de Meursault, the Meursault Paulee—Meursault is a famous winegrowing village in Burgundy (as well as the name of the narrator in Camus’ The Stranger, L’Etranger). Maybe cut that line. Or keep it in—Aujourd’hui, mama est morte. Ou peut-être hier, je ne sais pas—for the French majors among my readership. Where was I?

I stop dictating and pour myself more wine. I eat some bread and cheese. I continue:

The Meursault Paulee is a wine gala with great food that closes the annual Hospices de Beaune wine auction which takes place on the third weekend in November. There are a number of other major paulees in Burgundy in the fall. Internationally there are paulees, often with respect to Burgundy wines. (Or Bourgogne wines, as the regional wine board wants them to be called.) Places in the Loire Valley also now have paulees with their own wines, though a paulee is traditionally associated with Burgundy (Bourgogne).

I stop again. I’m pleased with the balance of my coincidental wine pairing: soft goat cheese and Chablis premier cru Vaillons. Or is any of this coincidental?

2011, Burgundy, October, the night of the Jag-u-ar, I attended a paulee, somewhere near Beaune. In a chateau? There were hundreds of people in the vast banquet hall. I dictate:

A paulee is the Burgundy version of a communal pot-luck dinner where most people bring wine instead of casseroles and pies and where the chefs, at least at the paulee that I attended, have Michelin stars associated with their names and are accompanied by enough sous-chefs to feed a battalion. Great food. But the wine’s the thing. When Burgundy wine producers, wine merchants and wine touring professionals invite you to a BYOB where they’re doing the BYOing, you know that you’re in for a treat. There was no tasting protocol to follow, as I recall. No spittoons. This was purely a sip-and-swallow event. We sat at round banquet tables for 8 or 10 people. Producers, distributors, sellers, friends of producers, distributors, sellers, hotel owners, tour organizers. They’d brought wine with which they had an intimate relationship. That’s what I remember most, the spirit of sharing and generosity by guests bringing a part of themselves; everyone was somehow related to the wine and the terroir, or the climats as they call their vineyard parcels in Burgundy. Six to eight bottles on each table. At least 30 different wines available in the room. And if you listened carefully you could hear each of those bottles saying, “Now. Do it now. I have to be drunk now.”

I laugh at that thought as I pour myself another glass.

Once we tasted the bottles on our own table at the paulee, we set out on collective or individual missions for bottles at other tables. We then exchanged or begged or stole a pour or a bottle from a neighbor, then from their neighbors, then from the neighbors’ neighbors’ neighbors, spreading good cheer along the way like a harmless coronavirus party.

I stop recording and try to remember who was at my table. No one particular comes to mind. Who invited me to that paulee?

From that sharing of things with which one has a personal connection, there develops a joyful, communal atmosphere. As reserved and uptight as the French can be in social settings, it didn’t take long at the paulee for everyone to stand up and do a Burgundy version of the macarena. They waved around white napkins while singing “Je suis fier d’être Bourgignon.” (I’m proud to be a Burgundian.) I stood up with them and sang that I was proud to know a Burgundian.

Yet for the life of me I can’t remember who the Burgundian was that invited me, or sat at my table, or drove me back to the hotel.

I carry my glass to the bookshelf in the living room / office and take down my Burgundy file box. I find nothing in it about the people I was with that weekend. But here’s the tasting list from the paulee of October 2011! On it I noted at the time what wines I’d liked. Apparently, I had a taste for the Bâtard-Montrachet Grand Cru 2006 Domaine Michel Picard among the whites. And among the reds the Corton Grand Cru 2007 Domaine Rapet struck my fancy, as did the Clos de Vougeot Grand Cru 2006 Domaine Bertagna.

I carry my glass to the bookshelf in the living room / office and take down my Burgundy file box. I find nothing in it about the people I was with that weekend. But here’s the tasting list from the paulee of October 2011! On it I noted at the time what wines I’d liked. Apparently, I had a taste for the Bâtard-Montrachet Grand Cru 2006 Domaine Michel Picard among the whites. And among the reds the Corton Grand Cru 2007 Domaine Rapet struck my fancy, as did the Clos de Vougeot Grand Cru 2006 Domaine Bertagna.

I won’t say that everyone was wasted, because wine folk don’t like the term wasted. Let’s just say that if the two words “social distancing” are saving us now, the two words that saved us then were “designated driver.”

I remember that fraternal feeling of the paulee, that sense that, good harvest or bad harvest, we were in this together. We were sharing something that we all felt concerned by and connected to. We had all brought something to the table.

But what had I brought to the paulee? How was I connected? Did I know anyone there? Did I speak with anyone? What was I doing there? Who invited me?

I look outside. The street is silent. A man walks a dog. No neighbors can be heard. A few birds call.

I sit at my desk with my glass of wine. It feels like I’m at the end of my article yet I’ve only written three lines: Thirty minutes after setting out southeast from Paris by train, you’ll notice the flat landscape begin to flutter. Then swells form. And when those swells rise to hills—hills covered with colza, wheat and barley and crowned with woods, cattle grazing down below—that’s when you know that you’ve entered Burgundy.

Again, I sense the outward traveling, resisting, exit-seeking mind calling for attention, turning me away from the text. This time it’s drawing me back into the kitchen, to the corner, where bottles of wine accumulate while awaiting an occasion.

Behind the cereal, the rice, the pasta, the onions, the aluminum foil, the plastic wrap and the paper towels, beneath a black table cloth, there are two wine racks with a dozen slots each, nearly full of bottles. I pick them up one by one and read the labels. Each one speaks of a trip I’ve taken or of someone I know or have known: a Bordeaux Clarendelle that was a gift from the producer the day after the fire at Notre-Dame; a Côtes-de-Meuse from Domaine de Muzy, where I stopped at between WWI sites in northeast France; a Cour-Cheverny, bought after a picnic at Domaine des Huards in the Loire Valley with Achmed and Guillaume; a Vin de Merde (it’s real name) that Pierre-Yves brought to dinner one evening having received it himself second hand; a Champagne G. Tribaut from a trip last fall to Hautvillers with Stephanie, which I now remember was also the name of the girl next door from second grade.

Hidden behind the wine racks, I discover other bottles that pre-dated the robbery, bottles that I must have intended to take into the basement but never did: a Châteauneuf-du-Pape Beaurenard 2011, a remnant of several days in Provence in 2013; two Saint Emilion Grands Crus, Château Gaudet 2011 and Château Soutard 2011, from a day in Saint Emilion on my way to Rauzan to visit Sophie and Jean-Stéphane; a forgotten Champagne Krug 2000 that Jean-Pierre brought for my birthday dinner some years ago. Each has a story to tell.

No—my two minds shout in unison—each has a story to share. Together they’ve come up with a plan: When friends feel comfortable gathering again, I’m going to have a paulee.

That’s it! Everyone is going to bring a bottle with which they have a personal connection, a story to share. I’ll invite Madame my neighbor. And Guillaume will come, he’s a great storyteller. And Achmed will be here, he’ll share. I’ll invite Scott, with whom I visited Chablis. And Véronique—that’s who invited me to the paulee in Burgundy! And the baker, who told me today that he’s just became a father. And the cheesemonger who sold me that delicious creamy goat cheese.

And you? Will you come? Get your bottle ready because you’re invited to a paulee. Yes, that’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to have a paulee. I would do it now, but it can wait. For now.

© 2020, Gary Lee Kraut

Share your own bottle story in the comments section below in 300 words or less.

Our father, of blessed memory, took the bottle of Maneschewitz down from the shelf every Friday night. The bottle was not special but it had a regal, sterling silver engraved chain hung around its neck which was inscribed with a Sabbath blessing. Our father looked priestly with a white kippah on his head, dressed in his Sabbath finest—a black suit, a starched white shirt and a royal red tie. The cotton table cloth was immaculately white and ironed and on it lay the two covered Challahs. The Sabbath candles flickered in the background. Carefully, he filled his silver wine goblet to the top. Then, he announced in a voice that brought us all to attention, “And the boys will say the kiddush! [the blessing over wine]” No one in my family could hold a tune except for me. Dad started us off, totally off key, and in total cacophony we sang in what was an agonizing experience to my ears but a soothing one to my soul.

Dad’s voice boomed over all of ours as we struggled to blend in. He stood straight and proud, glowing, with the goblet of Maneschewitz raised high. It was the best part of the week. All of us, who had gone our separate ways for the past six days, sat around that majestic table.

No wonder he was so proud surrounded by his wife and nine handsome children. Maneschewitz symbolized the coming together of family after a long, hard week. It spoke love and togetherness. Most of all, a bottle of Maneschewitz will always remind me of dear dad, his pride in his family, how he didn’t care about being off key and how it felt being enveloped in Sabbath light with the people dearest to me.

Thank you for sharing that beautiful bottle vignette. I could hear the off-key singing as I read it. Nine children! Kol ha’kavod!

Dad didn’t drink. Nor did mom.

But there were tiny, albeit rare, exceptions, like when it was hot and steamy in the summer, right before a thunderstorm, and dad was in the back yard, trying to coax his small garden’s lettuce, tomatoes and cucumbers to magically appear – he’d eventually give up, come into the house, tired, sweaty and frustrated, calling for mom to fetch him a cold beer. It was the ‘50s, after all.

Or during the Christmas holidays, when at a rare “special” dress-up dinner out (e.g. in a real restaurant that had tablecloths, vs. the local diner with its greasy plastic menus), mom would shyly order a Whiskey Sour — her only “real drink” of the year, which she’d sip, ever so slowly, throughout the meal. Aaaahh, was she thinking: is this how the movie stars do it? So glamorous!

As for me, after growing up in that, let’s just say, conservative environment, life expanded. But to this day I cannot explain my interest in, my still-curious palate, nor my ever-evolving desire to know more about wine – that glorious liquid that comes from grapes, such a simple little fruit, when you think about it. I remember watching, on an old black and white TV, Lucy and Ethel stomp them in a barrel in an attempt to make wine, hilarity ensuing. But the art, and intricacies, of actually doing so, however, going from vine to bottle – that’s something else entirely. It’s pure magic when done well.

One lifetime isn’t long enough to learn about wine, let alone sample, but you can bet I’ll keep on trying. With apologies to mom and dad, of course – or maybe thanks. Yes, many, many thanks.

Cheers!

Thank you, Sharon.

Wonderfully told! Cheers and santé to you as well.

Gary