… you live within a 3-minute walk of an extraordinary array of shops selling fresh produce, meat, fish, bread and pastries, as well as fine cheese and charcuterie. Within a 10-minute walk await dozens of restaurants and other eateries, offering everything from gastronomy to nostalgia by way of a culinary tour du monde. You don’t have to go very far to eat well. But you do have to leave home, because there isn’t much in your refrigerator this evening.

Working from home you managed to make lunch of the last of your cheese (a 24-month comté) and the last of your vegetables (a brown-edged endive), mixed with your homemade vinaigrette of Les Baux de Provence olive oil, Modena balsamic vinegar and Dijon mustard with honey and thyme.

Now, as night falls and your thoughts turn to dinner, your refrigerator offers you nothing but the Dijon mustard, a jar of apple-pear jelly from Normandy and a bottle of champagne. In the little freezer compartment there’s only a tray of ice cubes and a wine bag.

On a shelf beside the refrigerator there’s a bag of fusilli, a box of long grain rice and a box of couscous, with only olive oil and condiments to add to any of them. There’s cereal and a box of UHT 2% milk, for an emergency, but no need to panic. On another shelf there’s a collection of items that you’ve been given at press events and trade shows: several more jars of Dijon mustard (with curry and coconut, with Madagascar black pepper, with white truffles), from a food fair; a bottle containing a dry mix for making the chickpea crepe called socca, from a presentation about the Riviera; mignonettes (mini bottles, nips) of cognac, mirabelle de Loraine, genepi de Savoie, Grand Marnier, liqueur de chataigne and others, from various regional events.

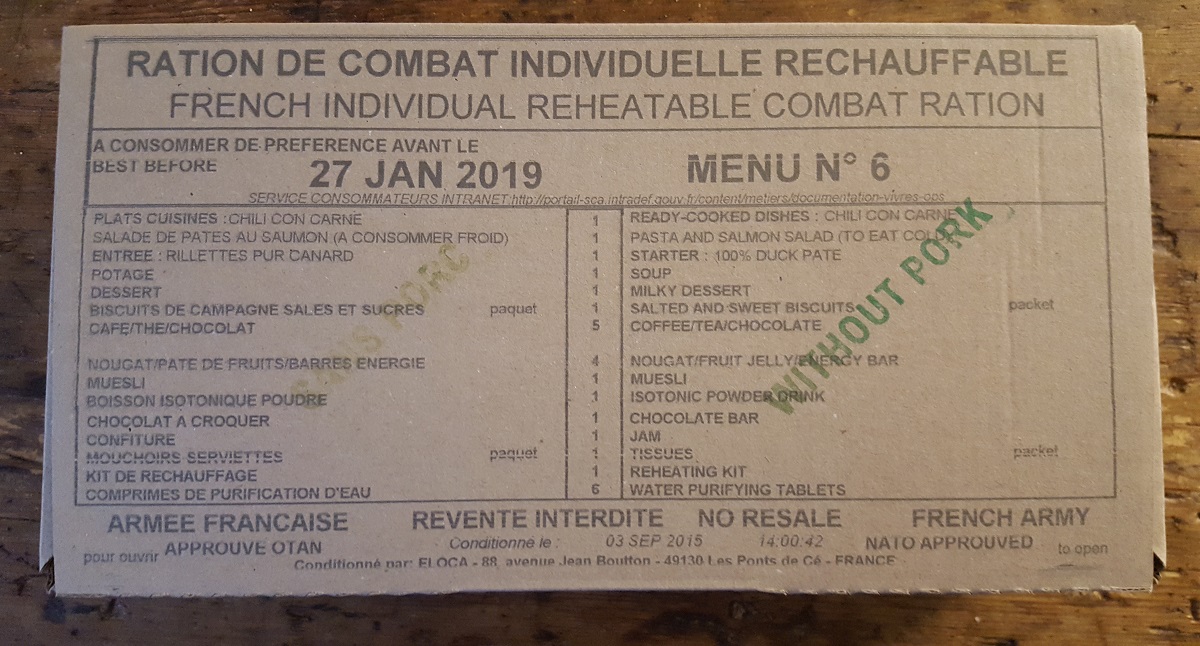

Then you see something you forgot you’d been given: a box of French combat rations, from the opening of an exhibition about war photography and photographers at the Army Museum in Paris. You retrieve it from the lower shelf.

It’s stamped with the expiration date January 27, 2019, nearly one year ago today. You wipe off the dust and place the box on the table.

Expiration date

Just then your intercom buzzes. It’s a friend who said he would stop by to pick up a pair of shoes that he’d left at your place when his feet were hurting from walking so much during the transportation strike and you’d lent him a more comfortable pair. That’s another story—and it’s this story as well since your friend’s work entails ordering food for the cafeteria of a public hospital. So his arrival is perfect timing—you’ll ask his advice regarding the expiration date on your box of combat rations.

“The box looks clean,” he says. “Probably no extreme temperatures in this kitchen. I’d say it’s good. But you’ll have to see how it looks inside.”

You open the box. Inside are a compact abundance of packets and tins. Your friend observes that nothing is dented or torn.

“It’s good,” he says.

“Do you want to stay for dinner?”

“No,” he says, “my feet hurt. But I’ll take the chocolate for the walk home, if you don’t mind.”

He takes the chocolate and the power bars and his shoes, and he leaves.

Duck rillette

You decide to go for it, beginning with the tin of duck rillette. Rillette is a kind of cold pulled pork except that in this case it’s duck, 74%, so a cold, shreaded confit de canard is more like. You try a spoonful. Cooked in fat (20%), it’s slightly greasy, as is to be expected, but not too salty. Tasty!

You open the packet of army biscuits to spread it on. First, a bite of dry biscuit. It tastes like an underbaked mix of wheat flour, water and skimmed milk powder. Is it stale or is it supposed to taste like that? Or are you just spoiled by easy access to some of the finest bread in the world?

You give the biscuit another try with some duck rillette. It’s still bad. So you chuck the biscuits and enjoy the rillette by itself. Quite good indeed. Ensuring that deployed soldiers enjoy their meal is essential for troop morale.

“An army marches on its stomach”

“Une armée marche sur son estomac,” said Napoleon Bonaparte. An army marches on its stomach. He offered a prize of 12,000 francs to the person who could come up with a means of preserving food to feed advancing troops. It took several years for a Frenchman, Nicolas Appert, to perfect a method for bottling fruits and vegetables, which he then extended to other foods. The use of metal containers was then patented several years later in England. By the second half of the 19th century tin cans had begun to supply armies, doing so on an industrial scale beginning with the First World War.

More than 30,000 French soldiers are currently deployed around the world: about 20,000 in operations in continental France and its overseas departments and territories and most of the rest in Africa (Dijbouti, Mali, Nigeria, Chad, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Senegal, and elsewhere) and the Middle East (Syria, United Arab Emirates).

A 10-person jury of military taste-testers in Rambouillet, 27 miles southwest of Paris, is partially responsible for approving of the contents of French combat rations. These rations, also NATO-approved, contain a hefty dose of protein along with a proper balance of carbs, lipids, calcium and omega 3.

Pasta and salmon salad

You gaze out the window of your quarters at the peace of Paris below. It’s momentarily disturbed by the bass horn of a bus intended to stir an ill-parked car without violence. Then the calm returns. You have nothing to fear but the fear of the expiration date itself.

Since you haven’t left your apartment all day, your nutritional and energetic needs differ from those of a soldier taking part in the Barkhane operation against Islamic terrorist groups in western Africa. Nevertheless, you’re still hungry.

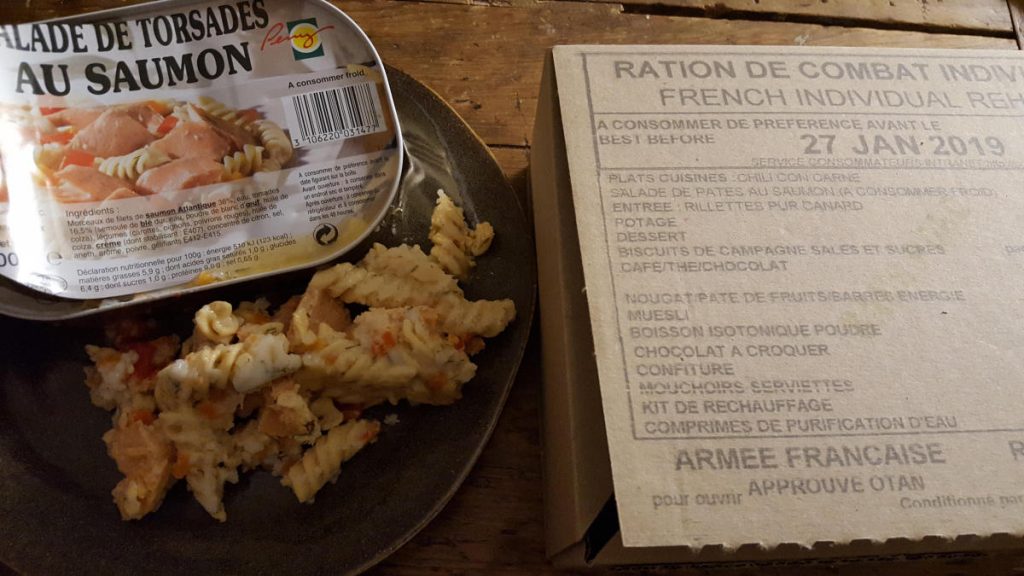

You snap open the tin of pasta and salmon salad.

Forking some onto a plate reminds you of why you preferred dry food over canned for your cat back in the day.

After several years in the can it takes a dish a bit of time to get used to fresh air, so you let it sit for a few minutes, like fine wine. When you do take a bite you’re surprised to find that the chunks of Atlantic salmon (36%) actually still taste salmony. Another bite, then another. The dish is bland, but salmon and pasta do make for a worthy combination. You could add some of the enclosed packet of salt and pepper, but you’re glad for the salad’s blandness because if it had any bite to it that might come from rot rather than from the bits of red pepper, carrot and onion.

You stop halfway through the contents of the tin. Enough calories for now. Furthermore, you don’t want to tempt fate. Better to call it a meal and stop there for the evening. See how you feel as the evening winds down.

You put the unopened packets and tins in the box and place it on the shelf. Doing so draws your eyes to the assembly of mini bottles of brandy. What the hell, you think, and you pour yourself a nip of plum brandy from Lorraine. A little schnapps could come in handy should tensions flare in the night.

Muesli with chocolate bits

The night was calm. Few shots were fired. You slept well.

Opening the curtains in the morning and looking out the window you see people stopping in at the bakery across the street. Fresh bread is just a few flights of stairs away, but you resist. You stay in your quarters. You won’t let fresh artisanal bread about which food journalists write glowing articles distract you from what you now see as your mission: getting three meals from your box of rations. If you had any butter the choice would be more difficult, but walking 300 yards to the fromagerie for some raw-milk butter from Brittany would be undisciplined. Besides, it’s raining. So you follow instructions as indicated on the pack of muesli with chocolate bits: Tear open. Add water to line.

The muesli tastes like wet chocolate-flavored paper with bits of lyophilized apple (4%). The wet paper with apples would have been fine, but you haven’t liked chocolate (13%) in your cereal since you were 10. Of course, many of the soldiers for whom the ration box is intended are barely a 20-mile hike and a few hundred push-ups past adolescence, so the chocolate chips do have their place on the menu. Whatever gets a soldier going, you guess. But you, you stop after a few spoonfuls and make yourself some soluble coffee.

Breakfast. Check.

Chili con carne

For three hours you work cleaning out your gun (desk), examining the map of an upcoming mission (crossing Paris during the strike), conferring with fellow men at arms about the night shift (a dinner party that you didn’t go to because of the strike) and checking in on the wounded (calling a friend who had an MRI on her knee after tripping over a scooter lying on the sidewalk). You’re quite hungry by the time noon comes around.

Returning to your ration box, you see what remains for lunch. If you’re going to get out of your mission unscathed you’ll have to get past the box’s most formidable expired dish: chili con carne. You hesitate and return to your desk. One o’clock passes, then two. You consider putting it off until evening. You’d rather not face it alone, so you text your friend who works at the hospital to see if he wants to come over for dinner. “Chili con carne,” you write. He responds: “Don’t each much carne anymore.” You text back: “I have a packet of dried soup, just add water, for you.” “Feet hurt,” he responds. Then radio silence.

You’re famished. At 14h20 you make your move. While the box indicates an expiration date of Jan. 27, 2019, the tin of chili con carne is stamped 04 2019, meaning that it expired only nine months ago—that’s three months in your favor. And not a dent. You remember what the foie gras and smoked salmon producer said about an old glass jar of foie gras: “It gets better with time. So as long as it’s still properly sealed you can consider the suggested sell-by date as simply a legal obligation.”

You unpack the heating kit and assemble the pieces. You light the cube and place the tin on top. The contents boil quickly. After a few minutes the cube is consumed; the flame goes out. You unfold the plastic spork. Despite its resemblance to dog food (but isn’t that the aspect of chili con carne anyway?), the mix of ground beef (32%), rehydrated red beans (25%), tomato concentrate, salt, pepper, cumin and onions is appetizing, hearty and filling. After downing half the container you feel satisfied. More than that, you feel triumphant.

Caramel cream

You pop open the caramel cream dessert to end the meal. It has the look and consistency of orange-brown house paint. You taste the slightest bit. It’s disgusting. Or was that because there was some chili con carne left on your spork? You wipe it off and try another slightest bit. Equally disgusting. This one has certainly turned, at least you hope so for the sake of French soldiers in Chad.

Your training and experience have taught you make quick, logical decisions for the good of yourself and your team. You wouldn’t lead anyone down that orange-brown path, least of all yourself. You set it aside and immediately return to the chili con carne for a few more sporkfuls to end your meal on a meaty note.

Taking risks

You’ve completed your mission of three meals. You forgo the second packet of soluble coffee. After 20 hours garrisoned in your hovel you’re ready to go out. You’ll stop in a café while out food shopping.

You place the trash and unopened packets into the ration box and take it downstairs to the garbage. As you exit the building you’re nearly hit by a scooter on the sidewalk. You wave to the baker across the street. You think of the young, dedicated, dutiful soldiers risking their lives during operations, making an unsafe world a tad safer, nourished by a tin of chili con carne. Completing a mission of eating three meals from a box of combat ration was just a game for you—a food game in one of the world’s greatest food playgrounds. It was all for fun, a personal dare to have a story to tell, like a 15-year-old American trying escargot for the first time. There was never any risk in eating the expired combat rations. Of course there wasn’t. If you were truly a risk-taker you wouldn’t be living in Paris.

© 2020, Gary Lee Kraut

I hear these rations have some sort of cheese in them that is delightful- a spreadable sort. However, I did not see it in your description.

Matthew. The photo in the article shows the entire contents of my box of rations. But not all boxes are the same. Gary

I grew up in a US Army family where my father was a food inspector. We tried interesting foods and odd tins where we went in the world. I still remember the powdered peanut butter and powdered cheese (cheddar?).

I love how field rations not only nourish, but bring your culture closer to you, it is a little bit of home when your are far away. I think that there is a whole more going on in the box than expired tins of food.

And a great article.