By John Gridley

Seventy-five years after the Liberation of France, a visit to the D-Day Landing Beaches and the WWII memorials, museums and cemeteries of Normandy remains high on the wish-list of Americans and other international travelers to France. Yet few are aware of the French role in the Liberation of Paris.

A new, free, highly informative museum, partially located in an air raid shelter used by the Resistance during the liberation of the capital, provides insights into the history of Paris and Parisians during the Second World War.

The Liberation of Paris

By mid-August 1944, as the Allies were breaking out from Normandy and simultaneously gaining a foothold in the south of France, General Charles de Gaulle, who had led the Free French in exile, disagreed with the Allies as to the urgency of liberating Paris. For the Americans and allies, Berlin was the prime objective in the effort to defeat Nazi Germany. Paris, of little strategic value, could be bypassed on route to the German capital. But for de Gaulle, liberating Paris was essential to the country’s future unification and independence, and that required securing military and political French control of the capital sooner rather than later.

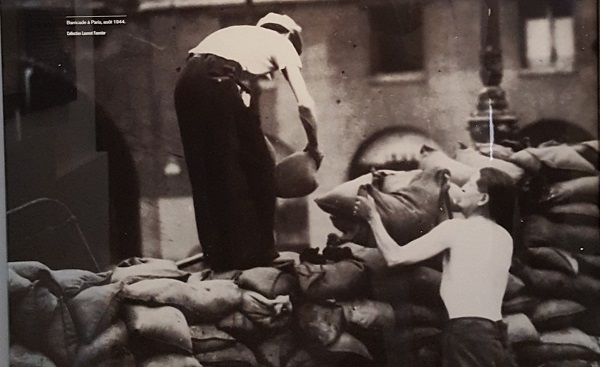

The issue was soon forced. Strikes had formed on August 10, growing to a general strike on August 18, and the insurrection began the following day. Skirmishes broke out and barricades were set up as a scrappy, lightly-armed Resistance fighters, policemen and civilians emerged from the shadows in an attempt to take on some 20,000 German soldiers and 50 tanks. On August 22 General Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, gave permission to the French 2nd Armored Division, commanded by Free French General Leclerc, supported by the American 4th Infantry Division, to enter the city.

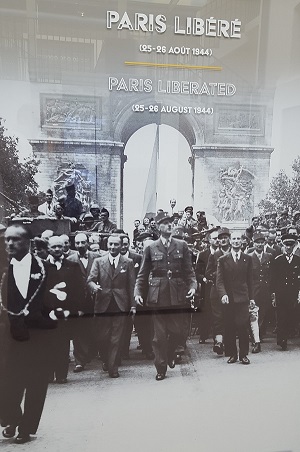

On the evening of August 24, Leclerc’s men entered Paris from the south and southwest, including along the road that would later be renamed Avenue du Général Leclerc. In the afternoon of August 25, German military governor General Dietrich von Choltitz, aware of the futility of fighting for control of the city in the face of advancing armies and unwilling to follow Hitler’s orders to leave the city in ruin, surrendered German forces in the Paris region. After four years of German occupation, the capital was free again.

On the evening of August 24, Leclerc’s men entered Paris from the south and southwest, including along the road that would later be renamed Avenue du Général Leclerc. In the afternoon of August 25, German military governor General Dietrich von Choltitz, aware of the futility of fighting for control of the city in the face of advancing armies and unwilling to follow Hitler’s orders to leave the city in ruin, surrendered German forces in the Paris region. After four years of German occupation, the capital was free again.

De Gaulle entered Paris that afternoon. He proclaimed at City Hall the continuity of the French Republic and the restoration of Paris’s lost nobility with a phrase famous in the capital to this day: “Paris! Paris outragé! Paris brisé! Paris martyrisé! Mais Paris libéré!” (Paris! Paris outraged! Paris broken! Paris martyred! But Paris liberated!) He went on to say that Paris was “liberated by itself, liberated by its people with the help of the French armies, with the support and the assistance of all of France…” with little mention of Allied efforts other than to acknowledge “the help of our dear and admirable allies.”

Had Paris been strategically important to the Allies and the Germans, there would have been far greater material damage to the city in an effort to dislodge the occupying forces, so, thankfully, little direct help was necessary from those “dear and admirable allies.” The museum gives them more due, yet this is appropriately and above all a French affair, and as such it offers foreign visitors insights into the German occupation, the French Resistance (and collaboration), the liberation of the capital and several of the homegrown heroes of the war.

General Leclerc and Jean Moulin

Located in the 14th arrondissement, across the street from the entrance to the Catacombs at Place Denfert-Rochereau, the museum partially occupies an underground air raid shelter that was used by Colonel Henri Rol-Tanguy in August 1944 as a command post to direct the Paris Resistance during its uprising. (The segment of avenue in front of the museum bears his name.) The command post presents period newsreels along with displays about its functioning during the uprising, including the critical role played by Rol-Tanguy’s wife Cécile.

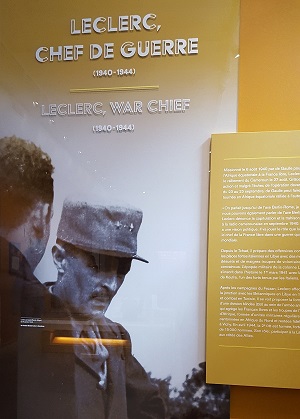

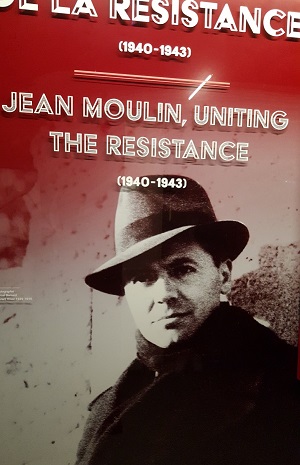

The museum, actually three related museums in one—it’s full name is the Museum of the Liberation of Paris/ General Leclerc Museum / Jean Moulin Museum—highlights the roles of General Leclerc and resistance organizer Jean Moulin, two French heroes from very different backgrounds who helped liberate France from within and without.

The museum, actually three related museums in one—it’s full name is the Museum of the Liberation of Paris/ General Leclerc Museum / Jean Moulin Museum—highlights the roles of General Leclerc and resistance organizer Jean Moulin, two French heroes from very different backgrounds who helped liberate France from within and without.

When France fell to the Germans in June 1940, General Leclerc, a military officer from a Catholic aristocratic background, escaped the country and over the next three years helped assemble and lead Free French forces in Africa, North Africa and Europe. Born Philippe de Hauteclocque, he changed his name to Leclerc to protect his family in France from reprisals. He eventually assumed command of the 2nd Armored Division, integrated into Patton’s Third Army.

Jean Moulin, meanwhile, was a Socialist and a rising prewar civil servant, the youngest prefect in France at the time of his nomination. After the fall of France, Moulin refused to become a pawn for the German occupation and focused on coordinating General de Gaulle’s activities and those of various Resistance groups within France. His work required clandestine travel (including a hazardous nighttime parachute jump) during trips back from London to meet with de Gaulle. Under constant threat of detection by the Germans, he negotiated with and unified most groups of the French Resistance in a single structure, becoming the first president of the National Council of Resistance in the spring of 1943. In June, several weeks after the council’s first official meeting, Moulin was arrested. He was tortured by the Germans—notably by Klaus Barbie, the “Butcher of Lyon”—and died of his wounds on July 8.

Jean Moulin, meanwhile, was a Socialist and a rising prewar civil servant, the youngest prefect in France at the time of his nomination. After the fall of France, Moulin refused to become a pawn for the German occupation and focused on coordinating General de Gaulle’s activities and those of various Resistance groups within France. His work required clandestine travel (including a hazardous nighttime parachute jump) during trips back from London to meet with de Gaulle. Under constant threat of detection by the Germans, he negotiated with and unified most groups of the French Resistance in a single structure, becoming the first president of the National Council of Resistance in the spring of 1943. In June, several weeks after the council’s first official meeting, Moulin was arrested. He was tortured by the Germans—notably by Klaus Barbie, the “Butcher of Lyon”—and died of his wounds on July 8.

Visiting the museum

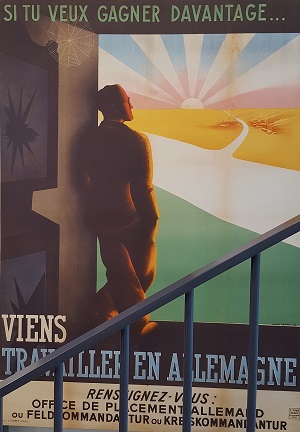

While the museum exhibits are heavy on archival material (letters, government decrees, posters, etc.), there are poignant historical objects, such as Moulin’s matchbox for concealing microfilm, Leclerc’s desert uniforms and a graffiti fragment from a Jewish family deported from Paris’s Drancy transit camp.

The museum also offers a variety of multimedia exhibits and interactive maps which show the location of key buildings requisitioned by Germans during the Occupation, Resistance strongholds and sites of fighting during the Liberation. At Barbès metro station, for example, a Resistance commando team, led by Colonel Fabien (after whom another metro station on line 2 is named) assassinated a German soldier in the summer 1941. The Hotel Lutetia housed the Abwehr, the German counterintelligence service, during the Occupation and then at war’s end was a processing site for the few returning French who survived German concentration camps.

Sections of the museum are punctuated by short films (all with English subtitles) presenting visions of life in Paris during the war, from pro-German propaganda newsreels condemning Allied bombing raids to instructions for women how to paint their legs in the absence of silk stockings. The final sections include extensive footage of outgunned Paris Resistance fighters battling the German Army and of de Gaulle’s famous Liberation speech (“Paris outraged!…”).

Spartan grey walls and a realistic soundscape give the interior the sound and feel of a military bunker. The subterranean command post resounds with the clack of invisible typewriters, ringing telephones and the whine of an air raid siren. As the exhibits progress to the darkest period of the war for Paris, the visitor descends into the basement of the building, and later, after the Liberation story, one emerges into a sunlit atrium adorned with French flags and offering views of the neighborhood where Leclerc’s American M4 Sherman tanks rolled to the center.

Other wartime memories in Paris

The Liberation Museum adds an important voice to the city’s extensive historical narrative of World War II. Elsewhere in Paris, memories of the Second World War can be viewed from other angles at the Army Museum at Les Invalides (sections devoted to de Gaulle, to WWII, and to the Order of the Liberation); at the Shoah Memorial in the Marais; at the Deportation Memorial behind Notre-Dame; on plaques commemorating Resistance fighters and deported Jewish school children, and in the form of pockmarks from fighting during the Liberation of Paris.

Evidence of damage can be seen on the southeastern corner of Luxembourg Palace (the Senate building), on the southeastern corner of the Palais de Justice (the central courthouse on Ile de la Cité) and on the wall of the Tuileries next to the Place de la Concorde, as well as elsewhere.

The material damage in Paris was limited during the war, but the city’s liberation brought about the death of 1000 resistance fighters, 156 soldiers of the 2nd Armored Division, 588 civilians and 3200 Germans, along with thousands of wounded.

Since 1945 the Cross of the Liberation, an order created by General de Gaulle, has been a part of the arms of the City of Paris.

Post-museum R&R

The museum draws visitors into its subjects so well that the curious traveler could end up spending over an hour and a half here (while the rest of the family visits the Catacombs?) before emerging to contemporary café life in liberated Paris. Numerous cafés are right nearby, but consider heading away from the bustle to a stroll and a sit one block away on Rue Daguerre, the neighborhood’s wonderful pedestrian food market street.

Practical information

Museum of the Liberation of Paris/ General Leclerc Museum/ Jean Moulin Museum

Place Denfert-Rochereau, 75014 Paris. Metro Denfert-Rochereau.

Open Tuesday to Sunday, 10AM to 6PM. No entrance possible after 5:15PM.

Tickets are free for the permanent exhibition, where displays present texts in English as well as French. The free ticket gains entrance to the command post in the air raid shelter, however only a limited number of people are allowed into the post at any one time, so visitors should request a timed reservation (not available online) to visit it as soon as they enter the museum in the hopes that tickets remain for the following hour.

The 100 steps down to the command post are steep, so a visit to that part of the museum could be difficult for visitors with small children or limited mobility. For those unable to access the command post, a virtual tour can be viewed on tablets available at the reception desk.

© 2019, France Revisited

What a wonderful article, thank you! Can’t wait to go here.

This is fascinating. I can’t wait to descend those 100 steps…