Paris, June 10, 2019—Late on a drizzly afternoon, having learned nothing and felt little from reading about and watching videos of the 75th anniversary of D-Day commemorations in Normandy, I went to visit the wild rabbits that inhabit the lawn of the Invalides. I took the metro to the Latour Maubourg station because when I’m alone I prefer exiting on the little square that seems to be a world until itself rather than onto the grand emptiness outside the Invalides station, despite it being named for the hospital and home for soldiers and veterans that Louis XIV launched in 1670, where the rabbits live. From Latour Maubourg I walked past the cannons on the opposite side of the dry moat and entered the complex through the freshly painted gate. People were exiting because the Army Museum had just closed but no one was entering and the military security officer on the entrance side was on his phone. I opened my jacket to flash him my weapon-free waist and chest, he nodded, then I walked on the large cobblestones to the lush lawn where the large, grey-brown wild rabbits of the Invalides were grazing, just as I knew they would be at this time of day.

I was pleased at their sight. Standing beneath my umbrella I counted eight, no, ten, no, twelve, or more rabbits scattered along the lawn and I felt contemplative as I watched them, though contemplative of what I cannot say. After a minute I heard voices behind me and looked back as two military officers walked by, and they looked at me, a man beneath an umbrella on the edge of the lawn as the museum was closing, and while one offered slightly more than a half-smile to say, “Yes, there are rabbits here,” the other offered slightly less than a half-smile to say, “Don’t you dare step onto that lawn.” I admit that I wanted to despite the little don’t-walk-on-the-grass sign at my foot, but not given to such transgression I stood there on the edge of the lawn, contemplating I don’t know what, as several rabbits looked over to me as though to say “Are you coming or not, because if you are we’re going to run away and if you aren’t we have to keep an eye on you, so make up your mind,” though my mind wasn’t indecisive at that moment, merely pleased, at peace, contemplative and somewhat lonesome for the touch of fur, unless that latter was my heart.

Yes, I did want to touch the rabbits, but I was nevertheless deeply satisfied just standing there, where I felt privy to a communion with nature in Paris on a grey, drizzly day, and perhaps it was that that I was contemplating on the edge of the rabbits’ lawn, that nature, that communion, that satisfaction, that peace, though contemplating may not be the right word for it since I felt, above all, a deep, still satisfaction. I was there, and so were the rabbits. And as though to compare my connection with the wild rabbits with my connection with the history of the military complex they inhabited, I went inside the courtyard of the Invalides, of the Army Museum, and took in the view of its vast orderly space, where Napoleon stood in the shadow on the balcony at the far end and where the gilt dome of Saint Louis beneath which he lay rose beyond, and while I still had in mind the lush green lawn and the hearty grey-brown rabbits, I also now had in mind the expansive and restrained emotion of the courtyard of the Invalides, its pride, its ambitions, its history and ceremonies (Dreyfus, Afghanistan, Saint Barbe), its grandeur.

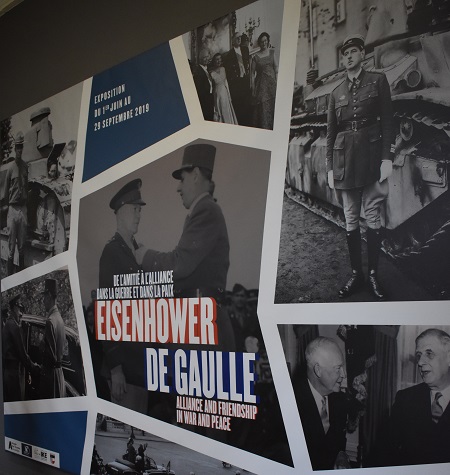

Between the rabbits and the courtyard, I’d been in the Invalides complex for less than 10 minutes and might have gone home then but I first wanted to use its rest room since I will sometimes decide that I’m going home then not arrive for several hours, either because that’s the way I am or because that’s the way great cities are. There were rest rooms, I knew, near the gift shop, but the museum had closed and I wasn’t sure to get in, but when, after crossing the courtyard, I asked the guard by the entrance to that portion of the building if the rest rooms were still open, he said “Go ahead, downstairs” with a surprising lack of obstruction and I realized that he thought I was on the premises for an event rather than as a straggling museum-goer. Indeed, when I came up the stairs from the rest room the guard pointed to my right, so I followed the direction of his finger and came upon a small crowd of well-dressed men and women entering a hallway outside of which a sign indicated an exhibition entitled Eisenhower – de Gaulle Alliance and Friendship in War and Peace.

A woman with a guest list stood by a desk by the entrance and asked my name, which I gave, and as I did I noticed someone waving in my direction from a few yards down the hallway, and even though he wasn’t waving to me, I waved back, leading the woman to not look at the guest list but rather to say “Oh, OK, I see, welcome” to which I replied “Thanks,” and entered the hallway gathering. I now felt obliged to walk up to the fellow who waved. He was a slight man with kind droopy eyes wearing a uniform the color of wet sand whom I recognized as General Alexandre d’Andoque de Sériège, director of the Army Museum. I introduced myself while shaking his small, warm hand and he said “Thanks for coming.” “My pleasure,” I said, leaving him to greet the person he had actually waved to, and as I turned I nearly bumped into General Christian Baptiste, former director of the Army Museum, wearing plain clothes, nice plain clothes, a suit actually. “Good evening, my general,” I said, and we shook a firm shake.

I looked around at the gathering crowd then down at my blue polo shirt and black pants and brown pleather jacket, clothes I hadn’t given much thought to when leaving home to visit the rabbits, and realized that I was conspicuously the only person present without a uniform, a suit, a skirt or a dress, yet I’d just shaken hands with two generals I’d recognized, so perhaps I did belong. In any case I played it cool and scholarly and began to read the panels of the Eisenhower-de Gaulle exhibition in the long corridor leading to the Museum of the Order of the Liberation. Though I knew a few things about Dwight Eisenhower and Charles de Gaulle and about their relationship concerning plans for D-Day and the Battle of Normandy and the Liberation of Paris, I hadn’t previously thought much about the parallels in their lives: they were born six weeks apart to religious and patriotic families; both were frustrated by their distance from the front during the First World War; both wrote texts promoting the importance and development of tank divisions at a time when both chomped at the bit of their hierarchy; both became generals; each approached the other warily while developing mutual respect after their first encounter in Algiers when de Gaulle began to form the French Committee of National Liberation (Comité Français de Libération Nationale) and sought American recognition.

I read some of the panels in English and others in French, depending on whether I could stand unobstructed closer to the left or the right, and, while the texts appeared to be equal in content, when I read in English I saw de Gaulle as a pompous Frenchman trying to represent in exile a defeated nation and who wanted to be considered its savior whereas Eisenhower was clearly the man of the moment, whereas when I read in French I appreciated de Gaulle’s ambition, his desire to exert Free French control so as to quickly return France to the role of a nation among nations, making him, too, a man of the moment.

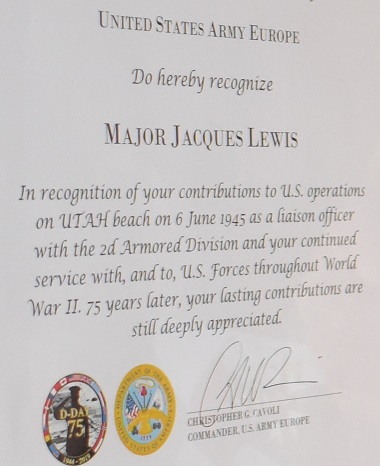

I stopped reading when General Alexandre d’Andoque de Sériège, as the museum’s director, walked up to the small podium set up toward the end of the hallway in front of the flags of France, Europe and the United States and began welcoming distinguished guests—a government official, French generals, American military attachés, foundation presidents—who in protocolar order went up to the podium to speak about French-American bonds, the Eisenhower-de Gaulle bond, D-Day and its 75th anniversary. When last the government official spoke she told of a man named Jacques Lewis, a military liaison who was the rare Frenchman to land on Utah Beach, and of his various deeds in favor of French-American military relations and the cause of victory. She said that he was now 100 years old and lived at the Invalides, and I realized that he was present though I couldn’t see him because I was five yards back and we were all standing while he must have been seated. A certificate given to him by the United States Army Europe was read in English and translated in French, and after the applause died down and General d’Andoque de Sériège invited the assembly to a reception, I made my way to the side of the podium until I stood before a handsome, well-dress, decorated man in a wheelchair, Jacques Lewis, who wore the Legion of Honor and other medals and had on his lap a large framed “certificate of appreciation.”

While Mr. Lewis looked to someone to his left I leaned forward to read to myself the certificate whose text I only half heard when it was twice read aloud about the United States Army Europe recognizing Major Jacques Lewis for his contributions on Utah Beach on 6 June 1945 as a liaison officer with the 2d Armored Division, at the start of a long march through France, and, surprised to read 1945 instead of 1944, I bent closer to be sure that I’d read it right, and when I looked up I again I was nose to nose with Mr. Lewis who offered a smile that said “I’m honored, moved, but overwhelmed, so many people fawning over me, I’m tired” and I replied with a smile that said “I came looking for rabbits and don’t really belong here be here but I’ve been to Utah Beach dozens of times and given dozens of lectures about touring Normandy and you’re 100 years old and landed on Utah Beach(even though your certificate mentions 1945) and are now a resident of the Invalides, meaning that you’re at once a living monument to Allied victory and heir to nearly 350 years of pensionnaires at the Invalides, so you represent the entire military history of a place that is now also home to wild rabbits, and since I know all this then I do belong here and would like to shake your hand,” and I did, a large, gentle, human hand that I then covered with my other hand as though to keep it warm.

While Mr. Lewis looked to someone to his left I leaned forward to read to myself the certificate whose text I only half heard when it was twice read aloud about the United States Army Europe recognizing Major Jacques Lewis for his contributions on Utah Beach on 6 June 1945 as a liaison officer with the 2d Armored Division, at the start of a long march through France, and, surprised to read 1945 instead of 1944, I bent closer to be sure that I’d read it right, and when I looked up I again I was nose to nose with Mr. Lewis who offered a smile that said “I’m honored, moved, but overwhelmed, so many people fawning over me, I’m tired” and I replied with a smile that said “I came looking for rabbits and don’t really belong here be here but I’ve been to Utah Beach dozens of times and given dozens of lectures about touring Normandy and you’re 100 years old and landed on Utah Beach(even though your certificate mentions 1945) and are now a resident of the Invalides, meaning that you’re at once a living monument to Allied victory and heir to nearly 350 years of pensionnaires at the Invalides, so you represent the entire military history of a place that is now also home to wild rabbits, and since I know all this then I do belong here and would like to shake your hand,” and I did, a large, gentle, human hand that I then covered with my other hand as though to keep it warm.

When finally I let go and straightened up a woman reached her arm out to hand me her phone and asked if I’d take her picture with Mr. Lewis, and I saw from her gracious height and steady coif and the way in which she put her hand gently on the veteran’s shoulder and looked for him to look to her (or to me, the cameraman) that she must be somebody, and as I was backing up to take the picture she was briefly distracted by someone who called out “Mrs. Eisenhower, when you have a moment…” and she responded “Just a moment” and I realized that I was taking the picture of Ike’s granddaughter, Susan Eisenhower, so after taking a few shots and after I handed back her phone and she said “Thank you” I asked if she would be kind enough to allow me to take her and Mr. Lewis with my own camera, and she obliged. “Thank you, Mrs. Eisenhower,” I said. “You must have had a busy week with all these ceremonies,” to which she responded, “Exhausting,” and we then talked briefly about the series of ceremonies and events (75th anniversary of D-Day, 50th anniversary of her grandfather’s death, etc.) that she’d been to and that I hadn’t, other than this, which anyway covered the essential. I seemed to remember reading someplace that she now lived in Europe and asked her as much, to which she replied “No, I live in Washington, D.C.,” to which I said, “I must be confusing you with someone else’s granddaughter,” and without skipping a beat she says, “Helen Patton,” to which I said, “Sorry about that,” and we both laughed as though it were an inside joke, though many people know that the two are as unalike as, well, Eisenhower and Patton. A woman then called out “Susan” and Mrs. Eisenhower said to me, “Excuse me” and I shook her hand, which was sincere and long and warm if not as fuzzy as a rabbit’s head.

As people walked away I finished reading the panels of the exhibition—Eisenhower and de Gaulle both became presidents; they had their differences but maintained mutual respect, they visited to each other; Mamie and Yvonne died one week apart; Charles and Ike died 18 months apart—then slowly followed this beau monde of generals and military attachés and foundation presidents and Mrs. Eisenhower into one of the Invalides’s refectory/reception rooms, where, after a glass of white wine and several canapés, I asked a woman with a star-spangled scarf who was momentarily standing alone if she could point out to me the president of The First Alliance Foundation, which was a partner in the exhibition and which I’d never heard of, and she could not only point out Carole Brookins, the foundation’s founder and chairman, but also Dorothea de la Houssaye, founder and director of The Normandy Institute, another recent organization, along with many of the French generals and American military attachés present, and when I told her that I was impressed that she knew everyone she said, “Don’t be, that’s what generals’ wives do in Washington.”

The French generals and American military attachés and foundation presidents were as numerous as rabbits on the lawn, yet more approachable I found as I shook their hands and talked their talk, and even if their palms weren’t fleecy they were genuinely warm and frank.

At the first hint of the gathering breaking up I took my jacket and umbrella from the rack and left.

The courtyard was quiet except for the sound of a gentle rain.

The lawns were empty, as the rabbits had gone into their burrows, yet I stopped there for a moment, beneath my umbrella, to silently thank them for my good fortune.

© 2019, Gary Lee Kraut