Toussaint Louverture’s prison at Chateau de Joux

© Alain Doire – Bourgogne-Franche-Comté Tourisme

Slavery is a crime against humanity. So decreed France in 2001, making it the first country to do so. What may seem to be a solely symbolic decree, akin to declaring the Jurassic era over, is actually a way of condemning the country’s own history with respect to slavery, something not every country is willing to do.

The law was adopted by Parliament on May 10, which was then decreed the National Day of Commemoration with respect to slavery. In particular, it recognizes France’s involvement in slavery and the slave trade for over 350 years until the definitive abolition of slavery in France and its colonies on law April 27, 1848. The abolition law, passed under the period known as the Second Republic, resulted in the liberation of 250,000 people from slavery.

Slavery had been outlawed in continental France since 1315, but with conquest of the Americas and European incursions into black Africa, France by the early 16th century become a full partner in the triangular slave trade between Africa, Europe and the Americas. Estimates vary as to the total number of Africans uprooted and enslaved in the Americas with European involvement (primarily Portugal, Spain, England, Holland, France) from the 15th to the 19th centuries, with 12-15 million Africans being the figure used along the Route. (Black slavery to countries north of the Sahara was long present, if on a much smaller scale, before Europeans arrived.)

While men, women and children were not brought as slaves to the transcontinental ports of Nantes and Bordeaux, certain French shipping companies actively participated in their transport and profited from slavery in the colonies.

Origins of the Abolition of Slavery Route

In the wake of the national decree declaring slavery and the slave trade crimes against humanity, a number of sites in eastern France and in Switzerland joined together in a thematic constellation under the heading the Abolition of Slavery Route.

Launched in 2004 with support from the UN and UNESCO, the Abolition of Slavery Route appears as a haphazard route on the map. Unlike other historic routes in France (e.g. wine, pastel, castle, abbey, Impressionists or Napoleon routes), there is no true unity of place to these sites , though historically the anti-slavery movement in France did develop in its eastern provinces and their connection with Switzerland.

Burgundy – Franche-Comté

Rare is the traveler who will actually follow the route from start to finish. This article concerns three sites on that route in Burgundy – Franche-Comté, a composite administrative region, comprised of evocative Burgundy on for its west portion and little-known Franche-Comté for its east portion. While the thirsty traveler will know of Burgundy first through wine, hungry traveler might initially encounter Franche-Comté through comté, which is among the most familiar raw-milk (cow) hard-pressed cheeses in France, and through poulet de Bresse, which is among the country’s top-quality chickens.

Each of the three major sites in Burgundy – Franche-Comté honor abolition presents a different facet of efforts between 1789 and 1848 to abolish slavery .

The House of Negritude and Human Rights

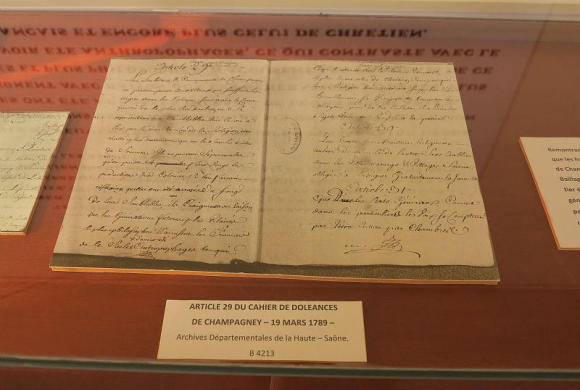

While the year 1848 marks France’s complete refusal of slavery in its territories, it was in the 1780s that significant anti-slavery movements began making their voices heard in France, as well as in Great Britain and the United States. On March 19, 1789, four months before the storming of the Bastille, citizens in the village of Champagney (Haute-Saône) drew up a charter of grievances (photo above) in which they wrote to King Louis XVI, “The inhabitants and community of Champagney cannot think of the ills being suffered by Negroes in the colonies, (…) without feeling a stabbing pain in their hearts.”

© CRT Bourgogne-Franche-Comté/Maison de la Négritude

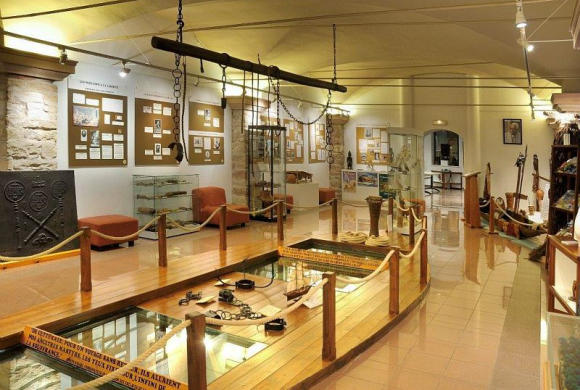

That expression of solidarity earns Champagney its place on the Abolition of Slavery Route. Here, in what is now a small town with a population of 3600, the House of Negritude and Human Rights (La Maison de la Negritude et des Droits de l’Homme) presents a reproduction of a slave ship and numerous African and Haitian objects that illustrate negritude (or the values of black civilizations around the world).

Château de Joux, the fortress prison of Toussaint Louverture

During the French Revolution, in 1792, the National Assembly granted full rights of citizenship to people of color. As early as 1794, the young republic appeared to be on its way to definitively abolishing slavery in its colonies when it promulgated a law to that effect. (It was at around this period that the term “crime against humanity” was first used.) However, that early French version of our Emancipation Proclamation wasn’t fully applied in all of France’s overseas territories in the ensuing years, and Napoleon Bonaparte, in his pre-Emperor role of First Consul, turned the country’s back on that decree. In 1802 he reinstate the legality of black slavery and the slave trade in colonies where former slaves weren’t yet all free.

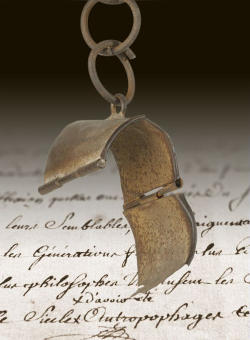

Shortly thereafter, Toussaint Louverture (~1743-1803), an Afro-Caribbean who had become governor of the island of Santo Domingo (present day Haiti) and leader of the rebellion against French rule at the time Bonaparte’s decree, was jailed and brought to the continent to be imprisoned in the Chateau de Joux. Louverture was born into slavery, was a freed and become a slave-owner himself in his 30s before climbing the military and political ladder through alliances with various sides over through the 1790s. The fortress at La Cluse et Mijoux (Doubs), which served as a state prison from 1690 to 1815, stands on the summit of a 3300-foot rocky outcrop guarding the entry to the water gap that is a natural passageway into Switzerland.

Louverture died a few months after his incarceration here. In 1804, within a year of his death, Haiti became a sovereign country, though bloodshed on the island would continue. His cell, situated on the ground floor of the fortress dungeon, can be visited (see photo at top of article).

The Anne-Marie Javouhey House

The same revolutionary body that would free slaves was also wary of the desire of the Catholic Church to reassert its dominance in the lives of the citizens of France. Born in Chamblanc in 1779, Anne-Marie Javouhey therefore grew into the faith of her ancestors in relative secrecy during her teenage years before taking her vows. Religious, as well as racial, reasons had often been given for allowing slavery from Africa. For Sister Javouhey and others, however, religion was instead a reason to oppose slavery, and former slaves should be converted to Christianity.

In 1805 she founded a religious congregation that would eventually take on the name Saint Joseph de Cluny, with a particular interest in education. The order, which still exists, became the first order of female missionaries. Beginning in 1817 and periodically for the next 25 years, Javouhey personally led a group of sisters on missions around the world, where they bore witness to the black slave trade. “Negroes are not deaf to the voice of morality nor to that of civilization,” she wrote to the governor of Guyana; “children of God, they are men just like us.” In 1835 Javouhey and her group obtained the right to oversee the education and conversion of 500 slaves. The first emancipations came in 1838 when she obtained the freedom of 149 who had been shipped to Mana, Guyana. Others would follow.

In addition to the family home of Anne-Marie Javouhey and a museum space located in the school that currently bears her name, the Abolition of Slavery Route sites in Chamblanc (Côte d’Or) include a remembrance forest, made up of 150 trees each named after one of the first freed African slaves.

Further information

The route continues in northeastern France and into Switzerland. For further information in French about the Abolitions of Slavery Route see its official website. The official tourism website of the Burgundy-Franche-Comté region can be found here in English.

Lodging

Near La Cluse et Mijoux (Château de Joux): The town of Pontarlier, several miles to one side of the fortress, has the 3-star Hotel Saint-Pierre and the B&B La Maison d’A Côté. Several miles to the other side and a half-mile from the Swiss border, Le Tillau is a chalet-like 11-room hotel and restaurant in the Jura Mountains.

Champagney: By Napoleon’s time already Champagney was known for its coal mines rather than for its point of view on slavery. The mid-19th-century manor of the director of coal mines in the area (which closed in 1958) is now the B&B Château de la Houillère. Just outside of Champagney, in the village of Ronchamp, the B&B La Maison du Parc also occupies a charming 19th-century mansion.