The First World War left its mark throughout the department of Meuse in northeast France, from Saint Mihiel to Verdun to the Argonne Forest. One hundred years on, these are not simply remnants of war and places of remembrance. They are also sights that invite questions and offer lessons with respect to the world today.

This article, including three videos, examines several sights relative to the Meuse-Argonne Offensive of the U.S. First Army in the fall of 1918: the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, Romagne 14-18, the Romagne German Cemetery and the Montfaucon Monument. It also notes other monuments to battles and regiments of the offensive and provides information about visiting other WWI sights in and on the edge of Meuse, along with hotel and B&B suggestions.

The Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery

Far removed from the pathways of American visitors in France but located within the heart of the zone of the U.S. offensive of the fall of 1918 between the Meuse River and the Argonne Forest, the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery of the First World War is the largest American Cemetery in Europe and may also be the most beautiful for the ways in which it gives visitors a combined sense of awe, serenity, natural balance and horror.

Entering on the east-west valley axis of this 130.5-acre site, the traveler can head north to the visitor center or south to the memorial. From the memorial, with its chapel and the names of 954 missing inscribed on its loggia wings, one stands above the 14,246 headstones that fan out and slope down to the valley before the landscape rises to a tree-framed lawn and the visitor center in the distance. From the visitor center, the eyes glides down that lawn to a circular pool before rising the headstone-dotted slope to the memorial and chapel on the ridge.

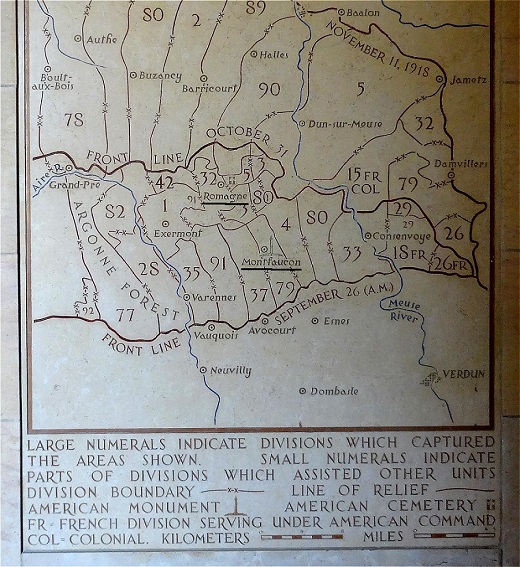

The graves, the memorial and the surrounding land honor the men of the U.S. First Army, under the command of John J. Pershing, who fell from fighting during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive which the Americans launched on September 26, 1918 and which continued until the Armistice of November 11, 1918. More than 1.2 million U.S. troops took part in the overall offensive, including many men whose names we associate with the Second World War and its aftermath, such as George Patton, Douglas MacArthur, George Marshall and Harry Truman. The battles of the offensive caused 117,000 casualties, including 26,000 deaths. This cemetery is also the commemorative site for over 2,000 men who died on the front in the Vosges, in the Champagne region and in Northern Russia.

The American Battle Monuments Commission and David Bedford, superintendent of the cemetery and memorial at the time, allowed us to film this France Revisited Minute last year.

Among those buried in this cemetery, its nine Medal of Honor recipients demonstrate the diversity of individuals and actions considered by the U.S. government to represent valor in combat. They are:

– Erwin Bleckley, a pilot from Kansas, who took exceptional risk in order to deliver supplies to “the Lost Battalion” of the 77th division;

– Marcellus Chiles, a captain from Colorado, born in Arkansas, who, though seriously wounded, made sure that the follow-up command structure was in place before allowing himself to be evacuated;

– Matej Kocak, a Slovak-born marine sergeant who entered the army from Pennsylvania, who drove out the crew of a German machine gun nest with his bayonet; 18% of the U.S. Army during WWI was foreign born;

– Frank Luke, from Arizona, a second lieutenant of the 1st Pursuit Group, who distinguished himself in fighting in the air and on the ground;

– Oscar Millar, a major from California (born in Arkansas), who continued the charge through the front line despite multiple wounds;

– Harold Roberts, corporal, a tank driver from California who, understanding the choice, saved his tank companion rather than himself;

– William Sawelson, a sergeant from New Jersey, who died crawling through machine gun fire to bring water to a wounded comrade; his headstone is capped by a Star of David, while the others on this list lie under Latin Crosses;

– Fred Smith, a lieutenant colonel from North Dakota (born in Illinois), who, though wounded, continued to return enemy fire until the men of his party were out of danger and who then refused treatment in order to carry out a second attack;

– Freddie Stowers, a corporal from South Carolina, who was instrumental in attacking and dismantling machine gun trenches; awarded the Distinguished Service Cross at a time when African-American weren’t eligible for the Medal of Honor, he posthumously became, in 1991, among the first to be upgraded to the highest American military award for valor.

Displays inside the visitor center provide a bit of information about the American Battle Monument Commission (ABMC) and the cemetery itself but little context for the offensive and the role of the American Expeditionary Force. Further reading and explanation is advisable for understanding the battles that took place in this region. Geographical and logistical information about the Meuse-Argonne Offensive can be found on the ABMC website.

One hundred years on, cemeteries such as this are not merely remnants of war and places of remembrance. They are also sights that invite questions and offer lessons with respect to the world today. They are occasions to consider and discuss the vocabulary of yesterday—sacrifice, human fodder, valor, racial separation, patriotism, pacifism, interventionism, jingoism, Europe, a league of nations—as they apply today.

Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, rue Rue du Général Pershing, 55110 Romagne-sous-Montfaucon. Tel. 03 29 85 14 18. The cemetery is open daily from 9am to 5pm, except December 25 and January 1.

The Romagne German Cemetery

Romagne-sous-Montfaucon was taken by the German Army in the initial phase of its invasion of France in 1914. It then remained an occupied village, removed from direct combat, for the next four years. During that time it served as a dressing station for soldiers wounded on the front. Much of Romagne’s wartime history is therefore that of an occupied village, with a growing German cemetery. It wasn’t until the start of the second phase of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, in October 1918, that Romagne became a battlefield itself before being liberated by American troops on Oct 14.

Romagne-sous-Montfaucon was largely rebuilt in the 1920s, including the village church, which was rebuilt with American funds. The village now has a population of about 200.

Romagne 14-18

France has some exceptional WWI museums, each with a different presentation and tone as it seeks to inform and educate and provide insights into the events of the surrounding region and of an era of just over 100 years ago.

Among the most notable of these are the museums in Peronne, Meaux and Verdun. Additionally, Thiepval speaks particularly of the involvement of British troops, Vimy of Canadian forces, and the American Monument (Cote 204) at Château Thierry of American forces. Each of these was created through and continues to benefit from government funding and publicity.

I add to this list of exceptional museums the odd-man out, Romagne 14-18, a unique museum of character that was created by the private initiative of Jean-Paul de Vries. In Romagne 14-18 he presents a portion of his collection of over 80,000 artifact found within 5 kilometers (3 miles) of the village and related to the wartime period.

Not only was there no government funding behind the creation of Romagne 14-18, but there is scarcely mentions of nations here. On the surface—a sometimes rusted, dirty, broken surface at that—de Vries’s enormous collection doesn’t try to explain or analyze or interpret the war other than lead the visitor to reflect on the life and perhaps death of soldiers. Beyond the surface, in its mass and in the specificity of its artifacts, Romagne 14-18 is at once a cemetery (of artifacts), a memorial (to those who used them) and an informal museum.

Son of a French father and a Dutch mother, de Vries, a dual citizen, now 50, first visited Romagne from Holland on a family camping trip when he was seven years old. He soon discovered a passion for finding and collecting artifacts of war. “At the time there were pieces everywhere,” he says, “and it was tolerated to go into the woods and bring home found elements.” (For many years now digging in the woods and the use of metal detectors has been formally prohibited.)

Asked when he first thought of displaying his finds, he says, “I’ve always exposed my collection.” At the age of 11 he brought pieces of it into school for show-and-tell, unaware that some of the shells he’d brought along were still potentially live. As he tells it, a classmate’s father, a policeman, came to the school that day and, seeing the collection, understood the danger. Soon the school was evacuated and the Dutch bomb squad confiscated the entire collection.

“After that I was no longer interested in arms,” he says (though there are plenty of rusted rifles and exploded shells in the collection). “It was the life of soldiers, their daily life, that interested me. A toothbrush, a cup, a shoe, that’s what life is; it isn’t a gun.”

From the age of 16 he begin driving down to Romagne with friends. “We came every Friday from the Netherlands for four or five years to search for wartime artifacts. There were dances, there were girls, but we especially came to search and dig.”

His pleasure for visiting Romagne and his passion for his growing collection let him to move to Romagne at age of 27. He hoped to find a job, but no was willing to hire him, perhaps, he says, because he suffers from ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew’s disease). But visitors and residents were interested in his collection, and occasionally he would receive donations.

“I didn’t choose this passion,” he says. “It chose me. It was along my path. My passion is what attracted people.”

His passion and his path have unearthed wagon wheels, shattered shells, canteens, portraits of soldiers and villagers, wine bottles, an rifles, countless horseshoes and shovel heads, stretchers, artificial limbs, and so much more, all with a 5-kilometer (3-mile) radius of the village. Five kilometers, he has said, is the distance he was willing to carry back his finds. He continues to take to the fields in search of war debris and is often brought material found by others, either outside or in attics and cellars. He has a 48-star American flag that, long since set aside at the American Cemetery, was given to him by a former superintendent.

De Vries is nearly always on hand to greet visitors and answer questions. He speaks Dutch, French, English and German. He has become a substantial actor in the local economy in a village that is otherwise short on businesses. With no café or restaurant near the museum, which occupies and old barn near the church, he created a cafeteria to feed student groups and passing tourists. (He has two other barns full of objects in storage.)

During the school year de Vries receives many school groups: classes of 8-12-year-old French students and 13-15-year-old Dutch students. “It’s nice to work with children,” he says. “They get my message. When someone takes off his helmet one sees the face of a human being, no matter what the color of his skin or his religion or his nationality.”

“It isn’t the war itself that interests me, but all that’s behind it, from the life of soldiers to the private interests of the war economy.”

Within the mass of object that de Vries has assembled, one can well imagine the cruelty, the violence, the wounded and the dead. De Vries doesn’t wish to glorify war or valor. There no good guys or bad guys in this collection. There are no winners or loser. For him, no artifact is too insignificant because every item has a story to tell in the life of a soldier: whether a key, a helmet, a shell, a shoe, a bicycle wheel, a pick-axe, a piece of barbed wire, a photograph, a wine bottle or a button.

Romagne 14-18, 2 rue de l’Andon, 55110 Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, 03 23 85 10 14. Open daily except Tuesday, noon to 6pm. Closed December, January, February. Guided tours possible. Entrance: 5€, free for children under 12. The café and sandwich shop at the entrance to the museum is open according to the same schedule.

The Montfaucon American Monument

One of the initial objectives of the U.S. First Army engaged in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive was to take a hill six miles to the south at the village of Montfaucon-d’Argonne, where the Germans had created a fortified lookout.

The Montfaucon American Monument, a 200-foot granite Doric column topped by a symbol of liberty, now stands on that site. It commemorates the victory of the U.S. First Army in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive while also recognizing the actions of the French forces that fought prior to that on this front. The monument stands above a cratered, wooded landscape and the ruins of the former village church. After the war, the village was rebuilt nearby, removed from this immediate site. The observation deck, 234 steps up, offers a vast view of the former battle zone.

The monument was designed by John Russell Pope, who was also the architect of the Jefferson Memorial and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C..

It was dedicated on August 1, 1937, as part of the final phase of monument dedications to the Great War just two years before an even greater war was ignited in Europe. Among those participating at the inauguration, were General John Pershing as former leader of the American Expeditionary Force and as chairman of the ABMC; Marshal Philippe Pétain, the hero of Verdun whose disgrace would come with the Second World War, and French President Albert Lebrun, who was more or less held hostage throughout that coming war for his opposition to Pétain’s Vichy Government. U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt also participated via a speech broadcast from overseas. A film of the dedication ceremony can be see here.

Montfaucon American Monument, 55270 Montfaucon-d’Argonne. The inside of the Montfaucon American Monument is open from 9am to 7pm March and April; 9am to 9pm May through September; 9am to 5pm October and November. Entrance is free. The outside can be seen year round. The monument is managed and maintained by staff at Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery.

Other monuments within a 25-minute drive

The Missouri Memorial in Cheppy, “erected by the State of Missouri in memory of its sons who died in France for humanity during the Great War 1917-1918.”

The Pennsylvania Memorial in Varennes-en-Argonne, on which is inscribed “In honor of her troops who served in the Great War among whom were the liberator of Varennes 1918 and in grateful appreciation of their service, this memorial is erected by the State of Pennsylvania 1927.” The memorial was designed by Thomas Atherton and Paul Cret. Varennes is known to the French as the place where Louis XVI, Marie-Antoinette and the royal family were held for the night after being arrested trying to flee the kingdom.

The Mound of Vauquois, whose cratered landscape speaks of mine warfare.

On the opposite side of the Argonne Forest, in Binarville (Marne), a marker and a monument indicate the site where Major Charles W. Whittlesey and his men of the 77th Division, known as “the Lost Battalion,” kept fighting despite being encircled by German forces. Of the 500 Americans who were encircled, about three-fifths were killed or wounded. Whittlesey, along with several other men of the battalion or of other units attempting to relieve them (including Erwin Bleckley noted above with respect to the cemetery), received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

– From Chatel-Chéhéry (Ardennes) one can take a walk in the woods in the footsteps of Sergeant York, a Medal of Honor recipient who became one of the most famous Americans soldiers for his wartime exploits in capturing a German machine nest of 132 soldier.

Other major WWI sights in Meuse

Visiting the region by car, one can see the sights in and around Romagne-sous-Montfaucon and many of those below over the course of two to three days:

In and around Verdun: Above all the Douaumont Ossuary, the nearby Verdun Memorial museum and the Forts of Douaumont and Vaux, followed, followed, time permitting, by the Victory Monument, the Underground Citadel and the Trench of the Bayonets (created with funding by an American donor).

In and around the Saint Mihiel Saliant: The Montsec American Monument and the Saint Mihiel American Cemetery. The Battle of Saint Mihiel, two weeks prior to the launching of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, was another major battle involving American as well as French troops. The terms “H hour” and “D day” are said to have been first used in planning for the attack on the Saint Mihiel Saliant. The cemetery actually lies just over the border from Meuse in Meurthe-et-Moselle.

Between Verdun and the Saint Mihiel Salient: The Eparges Ridge.

The official tourist site for the department of Meuse is www.meusetourism.com/en/.

See also The American Traveler and the First World One Sights of France.

Hotels and B&Bs in Meuse

Hostellerie du Château de Monthairons, a 4-star hotel in a 19th-century chateau, within a large park. The chateau, in the center of the region, was requisitioned by the American army during the war to serve as a hospital

Jardins de Mess, a 4-star hotel in Verdun.

Hôtel de Montaulbain, a 3-star hotel in Verdun.

La Maison Mirabeau, a B&B with guest table in Verdun.

Le Mont Cigale, a B&B with guest table in Vauquoi in the Argonne.

© 2018, Gary Lee Kraut