We drove toward Oradour-sur-Glane, 14 miles northwest of Limoges, on a hot day in mid-July. In the distance to our right, etching the brilliant sky, were irregular shafts of stone, the ruins of buildings. We were approaching a stark remnant of an atrocity of war, the vestige of a town where 642 men, women and children were murdered during the Second World War.

On Saturday, June 10, 1944, four days after Allied Forces landed on the beaches in Normandy, beginning the liberation of Europe, and while locals went about their business, Nazis from the 2nd Waffen-SS, an armored division, arrived without warning and sealed off the village. Starting in mid-afternoon, residents were rounded up, herded to the market square and separated by gender. Men were corralled into barns and other large spaces and machine-gunned; shots were aimed first at their legs to prohibit escape. Women and children were taken to the church and locked inside. A device was lit that caused suffocating smoke; the church was then barraged with hand grenades and set on fire. Later, the soldiers ransacked the village, set fires and used dynamite to maximize destruction. By eight in the evening, the German soldiers withdrew from the smoking ruins of Oradour-sur-Glane. Only six men and one woman survived the carnage.

After the war, Charles de Gaulle, with consensus from the French government, ordered that the “martyred village,” as it is called, remain shattered and charred as a painful reminder of the brutality of war. Oradour-sur-Glane has been labeled a historical monument since 1946.

A sign directed us to the car park. It was not crowded, and as we walked to the Centre de la Mémoire we looked toward where we had first glimpsed the ruins in a macabre attempt to see more than the tops of walls, but nothing else was visible; visitors must follow a prescribed route in order to experience the village. Along the way to the entrance is a tall column constructed of rough-hewn cubes of stone topped by a statue of a naked woman emerging from flames, her arms flailing upward in anguish. On the column is a line from poet, Paul Eluard: Ici / Des hommes / firent à leur mère / Et à toutes les femmes la plus grave / injure / Ils n’épargnèrent pas les enfants. (Here, men have made their mothers and all women the most serious insult: they did not spare the children.)

The Memory Center of Oradour-sur-Glane comes into view as a series of angled, irregular, rust-colored slabs thrusting up from the earth. The center’s website describes the design for the Memory Center as “non-architecture.” As you walk toward it, the peaceful, verdant surroundings of the Glane Valley disguise its purpose. But upon approach, the blade-like slabs purposefully rupture the scenery and the epithet “village martyr” appears on the entrance.

Visitors descend into the building which is sparse and utilitarian. There is a room off of the main space, a theater for informative films about the site. Upon entering, we were startled by a wall of black-and-white photographs of the 642 men, women and children who were massacred at Oradour-sur-Glane. Each minute or so an enlargement of one of the photographs appeared on a screen and then dissolved into another and then another, while names were spoken in a continuous, somber cadence. The faces and names of babies, children, teens and adults, individuals in every stage of life, forced us to confront human connections to an historic event.

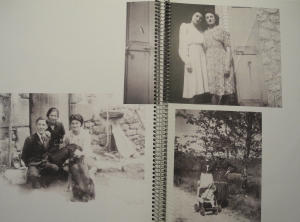

In a room adjoining the wall of photographs, scrapbooks were assembled alphabetically by family with materials and photos painstakingly collected and catalogued to convey the loss of homes, businesses, religious lives, careers, interests, personalities and voices. We turned the pages, looking into the eyes of the school teacher and the doctor, smiling at the faces of children peering over a balcony at a family gathering, recognizing the affection of a family for its dog, and feeling the joy of sweethearts on their wedding day. Through the photographs we pieced together a scene of village life like those we had seen in so many old films. The church, bakery, café, clothing store, other businesses and private homes became backdrops for people smiling and posing and walking by, revealing a vital community where life went on despite the war. Images of intimacy suggested passages that resonate in all societies. These were cherished moments meant to be looked at again and again in albums filled with the chronology of family. Today they were a preface for travelers about to journey through a moment of savagery.

In a room adjoining the wall of photographs, scrapbooks were assembled alphabetically by family with materials and photos painstakingly collected and catalogued to convey the loss of homes, businesses, religious lives, careers, interests, personalities and voices. We turned the pages, looking into the eyes of the school teacher and the doctor, smiling at the faces of children peering over a balcony at a family gathering, recognizing the affection of a family for its dog, and feeling the joy of sweethearts on their wedding day. Through the photographs we pieced together a scene of village life like those we had seen in so many old films. The church, bakery, café, clothing store, other businesses and private homes became backdrops for people smiling and posing and walking by, revealing a vital community where life went on despite the war. Images of intimacy suggested passages that resonate in all societies. These were cherished moments meant to be looked at again and again in albums filled with the chronology of family. Today they were a preface for travelers about to journey through a moment of savagery.

Visitors emerge from the austere, underground Memory Center into natural light and into the present. Passing a sign that declares “Souviens-Toi” and “Remember,” we walked the streets of Oradour-sur-Glane.

Visitors emerge from the austere, underground Memory Center into natural light and into the present. Passing a sign that declares “Souviens-Toi” and “Remember,” we walked the streets of Oradour-sur-Glane.

Sidewalks and roads and intersections declare that this village was planned and grew over time with commerce and life, but crumbled walls and rubble reveal a community long dead. We had anticipated the desolation and the ruins; we had even envisioned some specific remains from photographs. What we could not foresee, however, was our own emotional response. Rather than being transfixed solely by the material remnants of a village frozen in time since 1944, we felt our senses stunned by the horrific impact of life unexpectedly and instantly extinguished.

Throughout the occupation the Nazis maintained a precarious relationship with the puppet government in Vichy in an effort to control the civilian population. But the destruction of Oradour and its citizens was so barbaric that the German military realized it had to do something to deflect blame and suppress public outrage. Within days, in response to a protest from Vichy, the German military put together a document that accused the villagers of initiating the fight and blamed the deaths of the women and children in the church on an explosion of hidden ammunition kept by the villagers. They also ordered a perfunctory criminal investigation. The massacre was brought up at the Nuremburg trials, and in 1953 it was the sole focus of a military tribunal at Bordeaux. Neither of these investigations resulted in decisive understanding of the event. To this day, no definitive evidence exists as to why the SS attacked the village, but there are theories.

Systematic attacks upon civilians as a way to maintain order in occupied countries was an inherent Nazi strategy. This was regular practice in the Eastern Front, and as the war continued, violence against civilians became more common in France. After the Allies landed at Normandy, efforts by the French Resistance to disrupt German supply lines and communications increased. In response, orders were issued by the German military to crush the resistance without mercy. The resistance was particularly active around Clermont-Ferrand and the department of Corrèze, not far from Oradour-sur-Glane. Tactics of the resistance included attacks on troops and kidnapping. On June 9th, the day before the Oradour massacre, ninety-nine men were hanged in Tulle, capital of Corrèze, as punishment for partisan harassment of the Nazi 2nd SS division as it made its way north toward Normandy. It was this same division that annihilated Oradour-sur-Glane the following day.

An audio tour can be rented at the Memory Center, but we chose to walk the streets of Oradour on our own and construct a narrative from the simple plaques that identify businesses and their proprietors and homes and their residents. Each step reveals objects that support life; the remnants of tables, bed frames, bicycles and cars are wedged within the rubble of collapsed buildings. Buckets and rusted sewing machines sit in extant frames of windows or niches. Irregular, partially standing walls give testament to the bombardment of the village by the Nazis following the murders. Places that enrich and nurture a citizenry are ravaged. The roofless offices of the doctor and dentist, the wine shop, a girl’s school, an iron forge and the boulangerie are fragments of dirt and stone. The outline of a café has a single outdoor table; the automobile repair garage still has the frame of a door large enough for a truck, but no walls or roof to enclose it. Each vestige of life rests useless amid the disarray of charred stone and wreckage. Weeds push up beneath the rust and rubble of seventy years. Flowers bloom through as well. As we roamed the streets with other visitors, the uniformity of silence was remarkable. This is not a place for conversation or expletive even though each step leads to palpable savagery.

The main street meanders through the town past the market place, barns, fields, residences. It opens to side streets but eventually everyone takes a road that leads to the church. If a visitor expects solace, some divine absolution from this site, it does not come. A rusted baby carriage in the barren, roofless nave of the church is a reminder that the youngest victim murdered and burned was eight days old. The symmetry of the marble altar could be lovely as a relic aging naturally over time. Instead, the image of Christ that adorns it, rendered faceless by bombardment, and the empty rectangle of its tabernacle are reminders of congregants whose desperation and wails filled this cavernous room on June 10, 1944. Perhaps there are prayers uttered by visitors but they too are silent. Silence punctuates Oradour-sur-Glane.

A great deal of material exists about the destruction of Oradour-sur-Glane. Research has examined assertions that the village was a storehouse of armaments and that it harbored resistance fighters; information reveals that a number of Jews were among the dead. After the war a few Nazi soldiers were investigated for their part in the massacre, but only one was held accountable. As recently as 2013 Germany started a new investigation to locate soldiers who might have been involved. That same year German President Joachim Gauck stood with French President François Hollande to acknowledge the atrocity.

Photos, documents and maps can be accessed with ease, and the question “why” goes unanswered. But the significance of Oradour-sur-Glane is found in its very existence and in the power of its empty streets to elicit profound questions about humanity. As objects eventually rust beyond recognition, and rubble is eroded by nature, the village will survive the decay and abide the silence of visitors. And in its admonishment—“Souviens-toi,” “Remember”—Oradour-sur-Glane will continue to remind us to remember and to be vigilant.

Photos, documents and maps can be accessed with ease, and the question “why” goes unanswered. But the significance of Oradour-sur-Glane is found in its very existence and in the power of its empty streets to elicit profound questions about humanity. As objects eventually rust beyond recognition, and rubble is eroded by nature, the village will survive the decay and abide the silence of visitors. And in its admonishment—“Souviens-toi,” “Remember”—Oradour-sur-Glane will continue to remind us to remember and to be vigilant.

Text by Elizabeth Esris

Photos by Michael Esris

For practical information about Oradour and surroundings

The Memory Center at Oradour-sur-Glane, L’Auze, 87520 Oradour-sur-Glane. Tel. 05 55 43 34 30.

Situating Oradour: Oradour is located 14 miles northwest of Limoges in the department of Haute-Vienne, one of three departments in the historic region of Limousin, itself now a part of the vast region of New Aquitaine.

Never knew anything about this atrocity. I am sitting here at home watching an old tv series from the 1970’s called World at War and the final episode opened by solemnly mentioning this barbaric act of murder, not war. I just felt that I would like to dig deeper and find out more about this cowardly act. I now feel the urge to visit once this pandemic is finally over and we can travel.

David: I remember the World at War and its effect on me as someone still learning about the generation before mine. Oradour is a stunning reminder of man’s tragic ability to maim and destroy. It is an experience that does not leave you–more of humanity should see it.