As a former naval and shipbuilding town once surrounded by marshland, Rochefort can’t stake a claim to quaint streets, charming strolls or photogenic vistas. But nearly a hundred years after the closing of its naval shipyard, the town has played its historical cards in such a way as to make this an attention-grabbing, off-circuit destination for a day or an overnight.

This illustrated article examines the Rochefort maritime arsenal, the Naval Medicine Museum, the Rope Factory, Two Young Girls, The Hermione, the Raft of the Medusa and Pierre Loti. Other aspects of Rochefort are presented in Without Rochefort There Would Be No Begonias and Sylvie Deschamps, France’s Master Artist of Gold Embroidery.

* * *

As the crow flies, the town of Rochefort is situated 5 miles inland from the Atlantic. But you’re unlikely to find a crow taking the direct route. Even the gulls follow the twists of the Charente River 15 miles to Rochefort.

The foreign visitor, however, is more likely to arrive via a 35-minute drive, either south from the attractive old port town of La Rochelle or northwest from the impressive Roman and Romanesque remnants at Saintes. Beyond Saintes, Cognac and Angouleme lie further upstream along the Charente River.

Walking alongside the stern facades on Rochefort’s grid-plan streets, one might well think of Rochefort as a quiet town that has always looked inward. But Rochefort was created as an outward-looking town of national importance, with international ambitions.

The creation of Rochefort

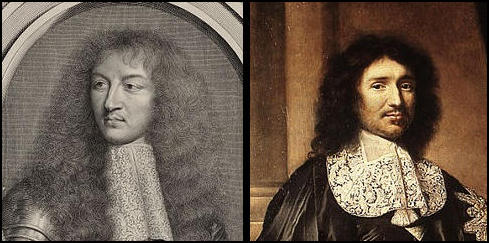

In 1666 the dynamic duo of France’s golden century, Louis XIV and his right-hand minister Colbert, aware of the need for France to beef up its maritime might as European powers bordering the Atlantic coast developed trade with and possessions in the New World, ordered the creation of a naval shipyard or arsenal at Rochefort.

Until then, France’s place as a European powerhouse typically meant deploying its force on land; its navy was a small affair. But with 17th-century globalization the English, the Spanish, the Portuguese and the Dutch rivaled for power on the high seas, and France risked missing the boat. Furthermore, while France’s Atlantic commercial ports of Nantes, La Rochelle and Bordeaux flourished, they were susceptible to enemy attacks and piracy.

So in a riverside zone, surrounded by marshland, close to the major commercial ports, within easy reach of the woodland and forests whose timbers were necessary for building a fleet, and defendable due to its position upriver, the Rochefort naval arsenal was launched.

A tremendous maritime enterprise was born, bringing together all of the various trades associated with such an enterprise. As it grew, a town of 14 east-west streets and 10 north-south streets was laid out.

Over time, Rochefort’s fortunes as a naval arsenal ebbed and flowed. It would be overtaken in importance by Brest, in the far reaches of Brittany, and later by Toulon, in the Mediterranean. Nevertheless, for 250 years Rochefort maintained a role in French maritime history.

The School of Naval Medicine

In 1722 the world’s first School of Naval Medicine opened in Rochefort. For the next 240 years it trained surgeons for the job of caring for sailors, and those surgeons became a part of the scientific team as the French navy around the world. The building where the school was installed in 1788 now houses the Naval Medicine Museum.

In 1778, Rochefort launched the construction of a 213-foot frigate called the Hermione. It was on that ship that, in March 1780 the Marquis de Lafayette embarked on a transatlantic crossing to deliver news to General Washington of France’s military support in the colonists’ fight against the mutual enemy, the English.

Rochefort was an important naval arsenal during that period. Some of the manpower came from forced labor as a penitentiary for criminals with lengthy sentences had been created here for just that purpose. (A more notorious forced-labor penitentiary was that of the maritime arsenal of Toulon, where the fictional Jean Valjean, the hero of Victor Hugo’s “Les Misérables” was held prisoner). The force-labor penitentiary or bagne of Rochefort functioned from 1766 to 1852. Living and working under harsh conditions, not only did the convicts provide labor for the navy, they also provided, upon precocious death, cadavers for the naval medical school.

The 19th century saw the development of the study known as phrenology which gave credence to the notion that the shape and size of the cranium reveals character, mental abnormality and the supposed inferiority of certain groups. The craniums of deceased criminals were studied here in an attempt to discern which cranial proportions signaled a propensity to one type of violent crime over another, e.g. distinguishing the physical traits of a murderer from that of a rapist.

Some of those “criminal” skulls can be seen at the Museum of the Naval Medical School among other displays of mid-19th-century medical know-how. Visits on the theme of phrenology and the penitentiary are occasionally held at the museum. Inquire at the Rochefort Tourist Office or directly at the museum.

The phrenology display is just a small part of the overall exhibit to the museum which presents a wide variety of displays relative to the concerns and methods of 19th-century maritime medicine and surgery. The building also houses an extensive historic library on the subject.

End of an era

As warships evolved in the latter decades of the 19th century it became increasingly difficult to justify maintaining a shipyard on a relatively shallow river. The death knoll for Rochefort as a shipbuilding town had been signaled several times over the centuries, and finally in 1919 the last warship to be constructed at Rochefort, its 550th, slid into the water. The arsenal closed eight years later. The port was partially dynamited by the German occupying force in 1944 with the approach of defeat. It was subsequently all but abandoned by the French navy.

The Young Girls of Rochefort

By the mid-1960s there was little life left in the old naval arsenal to identify Rochefort with its maritime past. The arsenal wasn’t dormant, it was in full decay. A town whose history had always led it to look outward could now barely face its own waterfront.

Then in 1966 a film crew came to Rochefort, awakening the town from its post-war slumber with bright colors, cheery music, movie stars and a whiff of flower power. Called The Young Girls of Rochefort (Les Demoiselles de Rochefort), the musical tells of two artsy young women who dream of love and life beyond Rochefort. Starring Catherine Deneuve and Françoise Dorléac (twins in the film, non-twin sisters in real life) and Gene Kelly, it was written and directed by Jacques Demy, with music by Michel Legrand. Hitting the big screen in 1967, the movie became such a cultural icon in France and remained so for so long that for several decades a foreigner hearing about The Young Girls of Rochefort when visiting France would have assumed that the town had no greater claim to a page in the history of France than being the backdrop of the colorful musical.

You can see from the trailer below how the movie would become an inspiration for La La Land (2016).

The Rope Factory and the Knot Tyers of Rochefort

Two Young Girls gave Rochefort a new taste of civic pride, but it was going to take much more than splashes of colors on the central square, some whitewashed walls and a few curious movie fans to face up to having an abandoned naval arsenal in the front yard.

Projects finally came to fruition in the 1980s. The Begonia Conservatory, though not in the arsenal zone, renewed Rochefort’s history of botanical exploration that accompanied its naval expeditions. After all, without Rochefort there would be no begonias.

More visibly, restoration of the Royal Rope Factory, the Corderie Royale, was undertaken. At 1227 feet long, long enough to twist hemp into 650-foot cables of rope, the corderie had been the first major royal construction project of the arsenal in 1666 and was to become the first project to draw attention back to the shipyard zone. Both tourism, in the form of presentations and exhibitions related to rope-making, and offices, with the presence of the International Sea Center, have found their place here, as well as an outstanding maritime bookshop. There’s a daytime restaurant, Les Longitudes, right nearby.

Visitors to the rope factory can learn through displays and demonstrations how string made from hemp was twisted into thick rope for the sailing ships of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

Sylvie Deschamps, France’s master artist of gold embroidery, may have the nimblest fingers in Rochefort, but knot tyers (mateloteurs in French) at the Corderie Royale are quite skilled at turning, twisting, braiding and knotting as they create traditional and contemporary rope pieces, both utilitarian and decorative.

The French branch of the International Guild of Knot Tyers, an organization created in the U.K. in 1982, is headquartered here.

The Hermione

Promoting a historic ropeworks can do only so much to bring townspeople and visitors from elsewhere to a former naval arsenal. What was missing was something that would instill civic pride and truly draw attention to the town: an actual ship.

Like neighborhood kids getting together to decide they wanted to put on a play, some elected officials and historical-minded folk came up with the crazy idea of actually building a warship at the old arsenal. It would need to be an evocative ship, one that called to mind the successes of the French navy, the role of France in the world and a historical figure who was famous and ambiguous enough that he hadn’t fully been claimed by either the right wing or the left. A tall order.

One ship identified with one man fit the bill: the Hermione, the frigate built at Rochefort, which took Lafayette to meet with Washington in 1780. It had been a journey that signaled France’s full involvement in the American cause, or more precisely in the hurt-the-British-wherever-you-can cause.

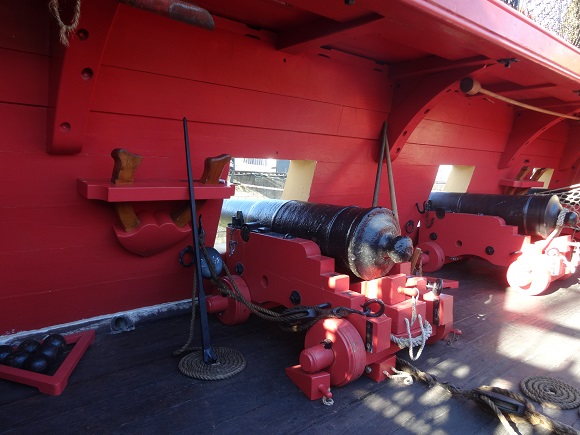

Turning a fantasy project into a reality took time. The municipally-backed non-profit Hermione – La Fayette Association was created in 1992 and construction finally began on July 4, 1997. While the original frigate took six months to construct, it took 17 years and a budget 25 million euros to building a full-scale replica of the 65-meter (213-feet) long frigate. The project required the wood of 2000 oak trees, 1 ton of hemp for caulking, 1000 pulleys, nearly 15 miles of rope for riggings, and eventually 32 canons, altogether requiring the creation of numerous workshops along the dock.

The region, department (sub-region) and town provided 4.8 million euros each for the budget and the European Union provided 1.5 million, while over 9 million came from members of the association, donations, sponsors/partners and visitors who came to see the construction site. Visitors could speak with the various artisans involved and learn about the various techniques and trades involved in building the replica.

Interest from the general public arrived slowly at first, but once the hull took form public interest rose with the ship. By the time the Hermione was completed in 2014 4.1 visitors had visited the dockyard to see the ship under construction.

A crew of 80 was formed, and in 2015 the Hermione took the ocean for a 17-day transatlantic crossing. She made calls along the U.S. eastern seaboard at Yorktown, Mount Vernon, Alexandria, Annapolis, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Greenport, Newport, Boston and Castine, then Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, before returning home via Brest and Ile d’Aix.

The crossing itself required a budget of about 5.4 million euros, with 3.15 million coming from American sponsors, partners and other sources.

The voyage was driven by the ship’s sails 95% of the time. A motor built into the replica was used as necessary, particularly to more securely navigate the entrance and exit to ports. Also breaking with tradition, about one-third of the crew members were women.

While the rope factory continues to please and inform visitors of all ages, the Hermione has become the face of the shipyard.

Dockside, visitors can see exhibitions about the ship and watch more or less active workshops regarding the sails, riggings, iron work and historical costumes. One can then step on board without a guide, but tours, given by crew members, are the more interesting way to go, especially if you’d like to know hear about sailing the high seas and ask questions about navigation and life onboard. Among those who made the crossing was Geoffrey Laulan, who started as a volunteer and has become one of the Hermione’s professional crew members.

Only one of the canons is an authentic 18th-century canon. The others are reproductions, unusable with cannonballs but suitable for fireworks displays.

In addition to regular visits, the Hermione also host’s special events, such as dinner events and concerts.

With Rochefort as its home port, the Hermione will set out from February to June 2018 for a voyage down the Atlantic coast and into the Mediterranean. It will call at La Rochelle, Tanger, Barcelona, Sète, Toulon, Marseille, Port Vendres, Portimao and Bordeaux, before returning home to Rochefort on June 16.

No frigate worth its salt would be complete with a ship’s cat.

The Raft of the Medusa

Less photogenic but claiming high historical honors in its own right is the replica of another French frigate called the Méduse (Medusa). Not the ship itself, actually, but the raft that was created from the ship’s masts and yards when the Medusa ran aground on a sandbank 50 miles off the coast of Mauritania while on its way to Senegal in 1816.

The outline of the true story of the raft of the Medusa is well known in France. It’s known through history books as well as art books, and especially through The Raft of the Medusa (Le Radeau de la Méduse) a large painting by Théodore Géricault (1791-1824), created while the news was still fresh. Today the painting is likely seen but ignored by most of the millions of visitors who come each year to the Louvre since it hangs in the gallery of monumental French paintings behind that of the Mona Lisa.

The Medusa was not built in Rochefort, rather at a shipyard in the estuary of the Loire River, just upstream from the modern-day shipyard of Saint Nazaire. But it was from Rochefort that the Medusa set out in 1816 on a mission to take control of Senegal, which the Treaty of Vienna had awarded to France. It was captained—poorly, cowardly and fatally—by an aristocrat who hadn’t commanded a ship in 25 years.

After a succession of navigational errors the frigate ran aground on a sandbar 50 miles from the coast. In order to lighten the ship, the captain commanded that a tremendous raft be made from the Medusa’s masts and yards. But as the ship began to list the captain ordered for the ship to be abandoned. There was a shortage of lifeboats and those were reserved mostly for officers, including the captain. The 151 soldiers and others are ordered onto the make-shift raft with little food and only five barrels of wine as nourishment. The raft, measuring 20 meters by 12 meters (66 feet by 39 feet) was so heavy with passengers that they stood in three feet of water.

If there was ever the intent to have the lifeboats tug the raft, the plan was quickly cut short. The raft was soon detached and went adrift, as the lifeboats made it to shore. Within two days, life aboard the raft was a hell of thigh-high water, extreme heat, delirium, fighting, rebellion and murder, soon followed by suicide and cannibalism as well. When finally spotted 13 days later by a passing ship, only 15 passengers remained. Of those, only seven survived to tell the tale.

The event shook France in 1816 both for the horror of the true tale and for the political scandal of the appointment of an incompetent aristocrat at the ship’s helm. The following year the captain was sentenced to three years in prison, a far cry from the penalty of death that many called for. That year Théodore Géricault began his own painterly investigations that would eventually give rise to his most famous painting. He actually spoke with and sketched some of the survivors in preparing the work.

Géricault’s 7m x 5m (23ft x 16ft) painting, which the Louvre refers to as “the star of the Salon of 1819,” depicts the imagined moment when a ship, potential rescue, is barely perceptible as a dot on the horizon. In that moment, as some die or agonize, the viewers sees an array of reactions and emotions relative to the tragedy and the possibility of rescue, from fatality and despair, it the view sees the human expression of fate of us all, from death to despair to optimism and hope.

In 2014, during the making of a documentary about the history of the Medusa and of Géricault’s painting, a full-scale replica of the raft was created and briefly set afloat. The replica can now be seen in the courtyard of the National Naval Museum at the Rochefort arsenal. On first view, it appears to be a jumbled array of posts and beams, as though something at the museum were under construction. The fuller view is upstairs.

The museum, which occupies the former residence of the Commanders of the Navy at the arsenal, is otherwise dedicated to more glorious moments in Rochefort’s naval history, with many scale models of warships and presentation of technical aspects of the shipyard. A current exhibition, running until November 6, 2018, presents naval uniforms.

Pierre Loti

The facades at 139 and 141 rue Pierre Loti appear as inexpressive as any in old Rochefort. But behind them lie the effusive and theatrical décor of the home of Pierri Loti (1850-1923), Rochefort’s most famous son.

Born Julien Viaud, Pierre Loti was his nom de plume. It might also be considered his stage name. Since childhood he had been interested in theatrics, adventure and exoticism. As Viaud he entered into a long career in the navy, while as Loti he also became an illustrator, a novelist, a travel journalist, a photographer, a collector (hoarder may be a better term for what he amassed) and a socialite. Throughout it all he was a traveler: Algeria, Turkey, Tahiti, Senegal, Japan, China, Morocco, Syria, Palestine, India, Egypt and more.

Loti liked to have himself photographed in the costumes of the places he visited, as in the two examples shown here. Nowadays, someone like Loti might become a master of the selfie and a million-hit travel blogger with his own travel show during which we’d occasionally see him hobnobbing with the titled and the famous from around the world. Loti himself was not famous merely for being famous, as would be the case today’s social networker. His fame came from the success of his writing, hence his election to the Académie Française. Though his novels have been largely forgotten, written in a bygone style, there is a brilliant level of detail and discovery in them.

He grew up on the street that now bears his assumed name, in the house that he would eventually purchase from his mother and transform in his own image. He later purchased the adjacent house. Each room was decorated to be reminiscent of a different time or place: the Chinese room, the Gothic room, the Japanese Pagoda, the Mosque, the Renaissance room, etc. He wrote little about Rochefort itself, but his work is rich with the outward-looking gaze that growing up in a port town in the mid-19th century might evoke: the desire to encounter distant lands and distant peoples, and the need to bring home pieces of foreign cultures.

Unfortunately for current visitors to Rochefort, Loti’s house, a historical monument belonging to the town, is closed to the public. Shuttered since 2012 because it requires thorough restoration and structural work and the hefty financing (about 12 million euros) to do so, the house won’t reopen before 2020.

In the meantime, the town’s Hèbre de Saint-Clément Museum provides an excellent introduction to the colorful character that was Loti and to his unusual home.

The Hèbre de Saint-Clément Museum

Nothing is more off-putting to a foreign visitor than a museum with a forgettable, multi-syllabic name, in this case that of the aristocrat who once owned the property. So ignore the name, but don’t forget that you’re in Rochefort because while this eclectic public museum might appear to be a handsome repository of random-abelia, its diverse parts offer a vision of the town’s history of seafaring, expeditions, colonialization and an interest in distant lands.

There’s a nod to The Young Girls of Rochefort, of course, but more importantly a thorough glimpse of Pierre Loti and a virtual visit to his house. The museum also presents a small beaux-arts collection, a display of objects handed down over the generations from a seafaring ancestor, and contemporary works from Oceania. The latter reminds visitors that there is more to Aboriginal art than the curiosity of colonizers but that vibrant arts and culture remain in areas that are far-flung from our point of view.

Restaurants, hotels, tourist information

For further tourist information about Rochefort and nearby sights along the Atlantic coast see the site of the Rochefort Ocean Tourist Office, Avenue Marie-François Sadi Carnot, 17300 Rochefort. Tel. 05 46 99 08 60.

Information about the wider area which includes Rochefort, Saintes and La Rochelle can be found on the site of the Charente-Maritime Tourist Board.

For an easy-going lunch or tea-time stop while at the arsenal, Les Longitudes, next to the Royal Rope Factory / Corderie Royale is open daily April to mid-November and during the Christmas-New Year holiday period. Otherwise closed weekends as well as early January to mid-February. Tel. 05 46 87 56 15.

In town, Patrick Bonnaud prepares finer cuisine at Les Quatres Saisons, 76 rue Grimaux, 17300 Rochefort. Tel. 05 46 83 95 12. Open Tuesday-Saturday.

A 20-minute drive from Rochefort by a little lake in the village of Trizay, Les Jardins du Lac is an attractive and friendly choice for seasonal gastronomy, prepared by Yohann Suire. 3 chemins Fontchaude, 17250 Trizay. Tel. 05 46 82 03 56. Open Tuesday-Saturday lunch and dinner and Sunday lunch. The restaurant is part of the Suire family’s quiet 3-star hotel of the same name. The hotel also has a heated swimming pool.

Back in heart of Rochefort there’s the 3-star Hotel Roca Fortis, 14 rue de la République, 17300 Rochefort. Tel. 05 46 99 26 32.

While some drive from Rochefort to La Rochelle and others to Saintes and points beyond, then this writer the train to Cognac. But that’s a whole other story.

© 2017, Gary Lee Kraut

Hello,

Quite enjoyed your article on Rochefort – I was there when the ship was out and Loti’s place was closed during renovation – nonetheless, may I ask, what are the people from Rochefort called? Lyonnais for those from Lyon – Parisians in Paris – Rochefort people are _________?

Thanks again!

Best regards,

Ron

An inhabitant of Rochefort is a Rochefortais (male) or a Rochefortaise (female). Collectively they are Rochefortais.