It is the 4th of August in Paris, clear and warm but not hot. With all my friends away on vacation and my usual activities not active, I am trying to think of a way to amuse myself. I decide to play tourist in this city where I have lived for over 40 years. My friends, before they left, suggested visiting museums. I like museums, but on this day they don’t appeal. I don’t want to be shut up indoors in such fine weather, nor do I want to compete with hordes of first-time tourists while looking at the exhibits.

An idea comes to me. Why not an afternoon in a park? I live near the Jardin de Luxembourg, in the middle-class 6th district. It is a formal garden in one part, with tennis courts in another. A fountain created at the initiative of Queen Marie de Médicis has been placed to one side. The garden now belongs to the French Senate. There I can enjoy watching ducks swimming in lines in the center pool, or admire 106 statues, but I must stay off the grass. I don’t feel like going to the Luxembourg Garden today. I know it too well. Since it’s vacation time in Paris, I’m in the mood to try something new and a bit less formal.

I consult Google, make a list of a dozen parks I don’t know. The one I choose is the Jardin de la Folie Titon, on the rue de Chanzy in the 11th district of Paris, a racially mixed working class area some distance from my home. I choose it because it sounds small and cozy, a real neighborhood park, but especially because I have never heard of it before.

I consult Google, make a list of a dozen parks I don’t know. The one I choose is the Jardin de la Folie Titon, on the rue de Chanzy in the 11th district of Paris, a racially mixed working class area some distance from my home. I choose it because it sounds small and cozy, a real neighborhood park, but especially because I have never heard of it before.

When I reach the park I learn that it does have some history connected with it. At the entrance, a sign tells me about it. The Folie Titon was a wallpaper factory built here before the French Revolution, and it participated in that event’s history.

A plaque on a wall on the nearby rue de Montreuil says that on April 28, 1789, a few days before the opening of the Estates General, the factory was burned during a people’s riot that was harshly repressed. Another plaque states that the first manned hot air balloon took off from this site October 19, 1783. The factory was rebuilt, but then demolished permanently in 1880. A middle school now stands on the site, built in the architectural style of the small factories which still exist in the neighborhood. It features broad windows across each floor, overlooking the park. The school is named Pilâtre de Rozier, after the 1783 balloonist.

A plaque on a wall on the nearby rue de Montreuil says that on April 28, 1789, a few days before the opening of the Estates General, the factory was burned during a people’s riot that was harshly repressed. Another plaque states that the first manned hot air balloon took off from this site October 19, 1783. The factory was rebuilt, but then demolished permanently in 1880. A middle school now stands on the site, built in the architectural style of the small factories which still exist in the neighborhood. It features broad windows across each floor, overlooking the park. The school is named Pilâtre de Rozier, after the 1783 balloonist.

The Folie Titon Garden is designed with a circular path around a big lawn, where today, couples and families are sitting or lying. There are no “keep off the grass” warnings here. An informational sign tells me about a lily pond at the far end of the park, recently installed to encourage “aquatic biodiversity.” There I see water lilies with tall reeds behind them, and a goldfish swimming around. In front of the pond are a variety of flowering and aromatic plants, honeysuckle, nasturtium, fuchsia, sage, and even a few vegetables, cherry tomatoes and squash.

I sit down on one of the numerous benches placed along the path, and watch the people around me. There are other bench sitters, most of them elderly white men. On the lawn there is a mother with a curly headed brown-skinned boy who looks to be about four. He is having a fine time chasing the butterflies flitting around the plants that separate the lawn from the path. He takes time out from his chase to greet me. “Bonjour,” he says. “Bonjour,” I reply. I can see his mother watching him from the lawn, but she does not get up. She must not consider me scary.

What could be scary is the group of teenage boys clustered near one of the park’s exits, not far from the lily pond. They are blacks and Arabs, and they are talking loudly. They stand very close together, and it’s hard to tell just what they are doing. Are they smoking weed? Could they be a gang? I am apprehensive, but relax when I see that the teenagers are ignoring all of the other users of the park, who are also ignoring them. Nobody seems afraid, so I will not be, either.

Two young women, one white, one black, dressed in summer casual clothes, pass my bench. They must live in the neighborhood, I think.

Just beyond me, they stop and look at the middle school. They have a Paris guide, and one reads to the other from it. Once they have finished reading, they take pictures with their phones, then they leave the park. “Why, they’re tourists!” I think to myself with amusement. I thought the only tourist in this little-known, out-of-the-way neighborhood park was me.

I sit for a while longer, enjoying the peaceful atmosphere, then I leave the park, too. I follow the path the rest of the way around the central lawn. There are fewer people on this side, few trees, no benches.

Then I see the Plaque. It is white marble, with lists of names in columns in black letters.

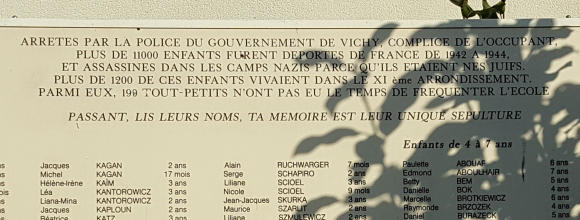

The Plaque reads:

“Arrested by the Vichy Government police, accomplices of the occupying power (Germany), more than 11,000 children were deported from France from 1942 to 1944, and murdered in the Nazi camps because they were born Jews. More than 1200 of these children lived in the 11th district. Among them, 199 babies who had not had time to attend school.

“Passerby, read their names, your memory is their only burial place.”

The children are listed by name and age, one by one, first the babies under four, then the children four to seven.

I feel like I have been hit in the stomach. None of my research on the Jardin de la Folie-Titon made any mention of this memorial to these deported children, the largest and most detailed of its kind that I have seen anywhere in Paris. Few people follow the circular path in that direction, where there are no trees, no benches. From the other side of the lawn, I myself did not notice the Plaque.

In 1942, when the deportation of these children started, I was seven years old, the same age as the oldest of them. In 1945, after the war ended and the concentration camps were opened, I saw a photo in Life Magazine showing heaps of naked corpses. I was ten, an age none of those Plaque children ever reached. I have never forgotten that photo, which became the root of my choice, as a historian, to study the fate of Jews in France under Vichy.

As I walk home through the Jardin du Luxembourg, my mind is still full of my discovery at the Jardin de la Folie Titon. My pretty, formal neighborhood park now seems stiff and stilted compared to what I just saw. I am so happy to live in this city where I can become a tourist and can find something that is more than just pretty, that has a personal meaning for me.

© 2017, Alice Evleth

Alice Evleth is a long-time American expatriate living in the 6th arrondissement of Paris.

This is a stunning article that confronts the reader with unexpected pain and sadness, much like the experience of the author.

Great article! Not only well written but fascinating with the twists and turns. Oh, the end!

If you go to the Camp des Milles, a Vichy concentration camp near Aix-en-Provence, now a museum, you will find a permanent photographic exhibition collected by Serge Karlsfeld of the children who were deported to Auschwitz.

In February 2017 France Revisited published an article about the Camp des Milles by Wendy Dubreuil:

https://francerevisited.com/2017/02/lion-feuchtwanger-les-milles-internment-deportation-camp-aix-en-provence/

I stayed in the 11th Arrondissement for a few days last month. It was couple of days before I noticed it, but right across the street from my lodgings was a small plaque on the facade of an École Maternelle bearing an inscription similar to the one the author describes. In some ways it was more affecting even than the Deportation Memorial on the Ile de la Cité because it was right there in the streets where the victims—some 1200 child deportees—had lived. A sobering moment in my tourist’s sojourn.