Sylvie Deschamps was 15 years old when she first held golden strings of cannetille.

“I loved its coldness and its glitter,” she says showing the fine gold-varnished coil that she’ll cut in pieces to embroider like pearls onto fabric. “When I held it in my hands I didn’t want it to stop. I didn’t find this vocation; this vocation found me.”

That vocation is gold embroidery. Thirty years later, Deschamps is France’s premier master of the craft—and the art. She holds the prestigious title Maître d’Art (Master Artist), which is awarded sparsely by the Ministry of Culture in recognition of those with unparalleled known-how of an uncommon craft and who practice it to an exceptional degree of excellence.

Since receiving the title in 2010, numerous haute couture and luxury good houses have come knocking at the door of Le Bégonia d’Or, the small workshop she oversees in Rochefort (Charente-Maritime).

When this visitor came knocking she immediately put away her high-tech magnifying eyewear and hid from sight the prototypes that she and her fellow gold embroiderer Marlène Rouhard were developing for luxury watchmaker Piaget. Exclusivity breeds confidentiality. Yet beyond such contractual obligations, Deschamps and Rouhard are welcoming, personable and quick to share their passion for their work.

Rochefort, a town of 25,000 in Charente-Maritime best known for its historic naval dockyard founded in 1666 and the 1967 musical comedy “The Young Girls of Rochefort,” would seem more apt to teach the twisting of hemp into rope to hoist sails then in delicate embroidery with cannetille or gold thread. But in this town once brimming with military uniforms bearing stripes and braids, fine embroidery was part of the fabric of the military economy. Restoration work then became a (small) part of the post-military economy.

Development of a Master Artist

Rochefort’s Lycée d’Enseignement Professionnel Jamain is France’s only vocational high school offering a diploma in gold thread embroidery. Both Deschamps, 45, and Rouhard, 33, studied there.

Diploma in hand in 1989, Deschamps immediately found work at Etablissements Bouvard et Duviard in Lyon, a workshop specialized in the restoration of religious vestments and other antique fabrics. Her time there deepened her understanding of embroidery’s technical and artistic aspects from as early as the 14th century. When her mentor there retired, Deschamps, still in her early twenties, became the “first hand” of the workshop, managing national and international orders and doing design work as well.

In 1995, after 6 years in Lyon, Deschamps returned to Rochefort for family reasons and entered a program to become an assistant professor at the vocational school where she’d once studied. But just two weeks in—and shortly after the creation of the gold embroidery workshop Le Bégonia d’Or by Marie-Hélène César with support from the town of Rochefort—the workshop’s first director left, and Deschamps was in the right place at the right time, with the right skills and experience, to assume the position. The craft that had found her at age 15 now found her at the head of a small workshop at age 24.

Le Bégonia d’Or

Le Bégonia d’Or (The Gold Begonia) has gold in its name because gold represents the pinnacle of the craft that has long had its place in Rochefort. As to begonia, it, too, is intimately related to Rochefort’s maritime history. An expedition to the Caribbean in 1688 under the patronage of Michel Bégon, intendant of the navy at Rochefort, gave birth to the classification of plants previously unknown to Europeans. One of them would be named begonia, after the expedition’s sponsor. (See this article about the Begonia Conservatory in Rochefort and this article about sights and people relative to Rochefort’s maritime history.)

Le Bégonia d’Or is a non-profit association that operates like a small business. In addition to original and restoration work, it holds workshops and sells embroidery kits and retail supplies. The workshop purchases their precious threads and cannetille from Carlhian, a company in Lyon created in 1870 to serve the silk trade. The company, known for its gold and silver thread, braids and trimmings, is the only producer in France of this range of gold products. Le Bégonia d’Or, in addition to using them in its own work, is the only retailer in France of Carlhian’s products.

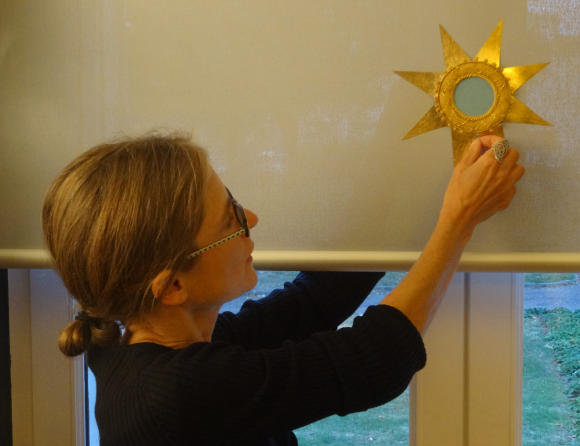

Sylvie Deschamps demonstrate embroidery with gold cannetille in this France Revisited Minute.

Knocking at the master’s door

It its early days, Le Bégonia d’Or was primarily called upon to restore the embroidery on military garments. There was also work restoring religious vestments (though Lyon is especially known for that type of work) and heraldic banners. Then as the reputation of the workshop and of Deschamps’ expertise grew so did the diversity of work requested of Le Bégonia d’Or.

A major turning point, both personally for Deschamps and for Le Bégonia d’Or (the reputation of the two is intimately intertwined), came in 2010 when Deschamps received the title Maître d’Art by then-Minister of Culture Frédéric Mitterand. The title is akin to the National Living Treasures of Japan regarding craftsmanship. Since its creation in 1994, only 132 men and women in France have earned the title of Maître d’Art, which one holds for life.

“It’s the reward of a long career,” says Deschamps. “I needed to show that I was capable of restorations, of contemporary creation and of performing techniques of great difficulty.”

The workshop now counts major brands in haute couture and luxury ready-to-wear among its clients: Chanel, Dior, Versace, Valentino, Ferraud, Saint Laurent, and others. Deschamps has also performed detail work on bags for Louis Vuitton, necklaces for Cartier and watches for Piaget.

“It’s thanks to the title that luxury houses came knocking at my door,” says Deschamps. “I would never have seen them otherwise.” The title not only brought these high-end clients but in some cases also created the need for gold embroidery. “We became a think tank for new ideas where a luxury house would say, ‘I need a Master Artist for this project and here’s a gold embroidery Master Artist, so how about integrating some gold thread embroidery into a watch or into a necklace.’ What I love is taking on the challenges that others aren’t able to take.”

She gives as an example a Philippe Starck project that involved her placing gold embroidery on the thick leather for a couch for the Cristal Room in Moscow.

She then goes into a back room of the workshop to bring out an exquisite fragrance bottle. In 2013, for the 160th anniversary of the creation of Guerlain’s emblematic Bee Bottle, originally designed for Empress Eugenia, the fragrance house gave carte blanche to nine Maitres d’Art to create work inspired by the bottle. While the eight others created one-of-a-kind displays for the bottle, Deschamps dared to decorate the bottle itself, wrapping it as though with a transparent imperial cape embroidered with golden bees. (At the time of this interview Deschamps was briefly in possession of the exquisite bottle as it is in transit between an exhibition and its owner who purchased it from Guerlain.)

The master and her student

“Having the title opens doors,” she says. “It gives access to fabulous places where art has its rightful place. It gives real visibility and prestigious orders.”

It also carries with it the obligation of taking on a student to whom the title-holder transmits her know-how, her savoir-faire.

Deschamps didn’t have to look far for her student. Marlène Bouhaud was already here, working alongside and being mentored by Deschamps at the Bégonia d’Or for five years before Deschamps received the title Maître d’Art. Recognizing each other as master and student was simply a formality, one that also placed Bouhaud in a class of her own among the gold embroiders in France.

Bouhaud was already familiar with sewing and embroidery from an early age through family heritage, but it was an encounter with Sylvie Deschamps at the age of 15 that gave her a glimpse of the beauty that could be created with gold and silver embroidery. Like Dechamps at that age, Bouhaud also felt drawn to the feel and shine of gold cannetille.

While still a teenager she showed Deschamps some of her embroidery work. Says Deschamps, “When I saw that I said to myself ‘Wow!’ What she’d done was already perfectly executed, with a regularity in the embroidery that already pleased me. Later on, when she completed a training workshop [at the Begonia d’Or], I saw that she had rare qualities: she was an excellent technician and she was passionate.”

Deschamps welcomed her in as a salaried employee in 2005.

There is additionally a third set of hands working at Le Bégonia d’Or, those of Thierry Tarrade. He embroiders as well, though not at the level of Deschamps and Marlène, and is largely involved with organizing training workshops and conducting initiation and intermediate workshops (levels 1 and 2). He also happens to be Deschamps’ companion in life. They first met 30 years ago, at the same time that she encountered the gold cannetille.

Deschamps hesitates when asked if she would be willing to take on another student to the extent that she has with Rouhaud.

“I don’t know. It happened so naturally with Marlène because she’s passionate about the work. It would have to be the rare pearl with both the technical aptitude and the passion,” she says. “Every ten years there might be someone about whom I’d say ‘Oh, she’s got something that the others don’t have.’ Still, even with the rare pearl I don’t feel that I’d have the time.”

The Future of the Bégonia d’Or

To hear Deschamps and Rouhaud speak about the intricacies of their work and the number of hours required for each piece, it’s a wonder that there are enough hours in the day to accomplish all they do. Meanwhile, they continually develop new projects. Le Bégonia d’Or is now a trademark for jewelry and other works. Their pride themselves on a production that is 100% French: leather from Paris, buttons from Jura, gold thread from Lyon, design, embroidery, creation at the Le Bégonia d’Or.

“We aren’t functionaries of embroidery, that’s for sure,” says Deschamps. “But it’s true, we both lack time for research, sampling and creating unique pieces.”

Deschamps workshop remains a small structure, and despite its sizable reputation there’s competition in this rarefied domain in France. Students graduating from Rochefort’s vocational school program with a diploma in gold embroidery, perhaps a dozen per year, may find work in the luxury and restoration fields.

“What will save the workshop in the future is its ability to respond to orders that others aren’t able to treat because they don’t have technical expertise or the innovative techniques to do so. Because that requires veritable sacrifice. Yet it’s the work we love to do, Marlène and I. We like to be pushed to the extreme of what is most difficult. The challenges change and we have to be able to meet those challenges. And that’s great!”

Rouhaud, now 33, is a trusted student and co-worker. “She’ll eventually be able to take over if she wants,” says Deschamps.

Asked if she dreams of being one day named Master Artist in her own right, Rouhaud says that it’s too early to think about. She says that she still has much to learn technically from Deschamps and that she must especially develop her creativity with respect to embroidery. Furthermore, in order to become a Master Artists in the same field she would have to be capable of proving that she brings something to the art that her current master doesn’t have. A high bar indeed!

Where does a Master Artist go from here?

“I was never avid about entering competitions,” says Deschamps, “but I’d like to enter another competition through the Bettencourt Schueller Foundation called Intelligence de la Main [Intelligence of the Hand].” The Liliane Bettencourt Prize rewards savoir-faire, creativity and innovation in the field of creative craftwork based on a specific work and is open to French and foreign craftsmen living in France. “Now I have to find the idea and the time.”

Asked if she can imagine practicing her moveable skills elsewhere than in Rochefort, Deschamps says that for now she’s happy to be here and to develop the workshop. “I believe deeply in the potential of this town,” she says. “This town has some beautiful tools and needs only play its cards right to become better known.”

Rochefort’s historical reputation has long been as a place that one left to sail elsewhere. Even the movie “The Young Girls of Rochefort” takes as its premise that the girls in question want to leave town. Now, though, thanks to the construction of the replica of the 18th-century frigate the Hermione which calls this its home port; thanks to showcases of its maritime history at The Royal Ropeworks and the Maritime Museum; thanks to the presence of Europe’s most important begonia collection, and thanks to the growing reputation of Le Bégonia d’Or and its Master of Art, the pleasant town of Rochefort has become a destination in its own right.

Le Bégonia d’Or

Bureau 11

10 rue du Dr Peletier

17300 Rochefort

Tel. 05 46 87 59 36

www.broderieor.com

The workshop may be visited by appointment only, Monday-Friday.

Also see Rochefort: Ships, Shipyards and Seafarers and Without Rochefort There Would Be No Begonias.

© 2017, Gary Lee Kraut.

An earlier version of this article appeared in The Connexion.