Aix-en-Provence may call to mind fountain-side cafés, the work of Cézanne, aristocratic palaces and the scent of lavender, but just several miles from the sunny heart of town lies a cautionary tale: the Camp des Milles, the only large French interment and deportation camp from WWII that is preserved and open to the public. Today the camp houses an educational memorial center with a year-round program of events.

In September 1939, when France declared war on Germany, the Camp des Milles interned so-called “enemy subjects,” largely meaning citizens of Germany and Austria living in France, in more than 240 camps around the country, including a former tile factory in the village of Les Milles. By the following June Les Milles was known as the camp of artist due to some 3500 artists and intellectuals being detained there. Among them was Lion Feuchtwanger, a Jewish German writer.

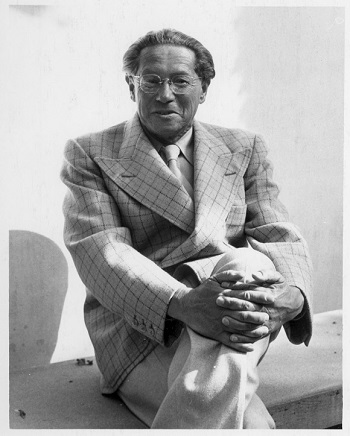

Born in Munich in 1884, the son of a Jewish factory owner, Feuchtwanger became a well-known writer who tried to warn the world about the dangers of Hitler and the Nazi party. As early as the 1920s he predicted many of the Nazis’ crimes in his book “Conversations with the Wandering Jew.” His book “Jud Süß” (Süss the Jew) would be distorted by the Nazis, who turned it into an anti-Semitic feature film. Heinrich Himmler had it shown to SS units and Einsatzgruppen paramilitary death squads about to be sent east on their murderous assignments.

When Hitler rose to power in 1933, Feuchtwanger was on a book tour in the United States. There he met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. While in the U.S. he learned of the confiscation of his properties in Germany and the burning of his books. The German Ambassador to the U.S. advised Feuchtwanger not to return to his homeland. He took his advice but returned to Europe. Lion Feuchtwanger and his wife Marta settled down with other German exiles in the seaside town of Sanary-sur-Mer, between Bandol and Toulon in southern France.

“We were in paradise, against our will,” he wrote. Although his books were banned from publication in Germany, the high circulations of translations enabled Feuchtwanger to have a comparatively comfortable life in exile until the outbreak of the war.

It was then, in September 1939, that Feuchtwanger, like other Germans and Austrians living in exile in France, was first interned at the Camps des Milles. Remarking on the irony of the internment of what were essentially anti-Nazi refugees, he wrote: “the responsible authorities know perfectly well that the spies, the saboteurs, the Nazi sympathizers were to be sought quite elsewhere than among us.” Recognizing this, the authorities released Feuchtwanger after several weeks.

The Devil in France

But the war situation and the attitude of the French government changed in early 1940 Feuchtwanger was arrested and interned there a second time. In his memoir “The Devil in France” he speaks of the deplorable conditions of that internment.

Republished in English by USC (University of Southern California) Libraries in 2010, The Devil in France (subtitled “My Encounter with Him in the Summer of 1940”) provides an intimate account of Feuchtwanger’s thoughts, snippets of his conversations and details of his survival tactics. Although Les Milles was not a work camp, Feuchtwanger recalled how, “under the sharp command of a sergeant,” he and his fellow inmates were forced to make neatly stacked piles of bricks. The bricks would later be torn down and piled up in another place. It made him think of the verse from Exodus “in which,” he wrote, “the children of Israel are forced to bake bricks for Pharaoh of Egypt to build the treasure cities of Pithom and Raamses.” So he chanted “Pithom Raamses… Pithom–Raamses” as he mechanically tossed bricks to his neighbor.

In the memoir he tells about the tiles, the bricks, the cramped spaces, making his bed directly on the floor out of straw, setting it off with more bricks, breathing in dust until his lungs bled and dust even in their inadequate food, the boredom, the lack of privacy. When not lifting bricks, the inmates spent much of their days in the dimly lit dormitories.

In the morning, he wrote, there were long lines to go outside to a handful of filthy latrines that were controlled by Foreign Legion detainees, some of whom had fought for France for decades and were maimed. One could tip the Legionnaires to get moved up to the front of the line. The Legionnaires also ran much of the camp’s black market.

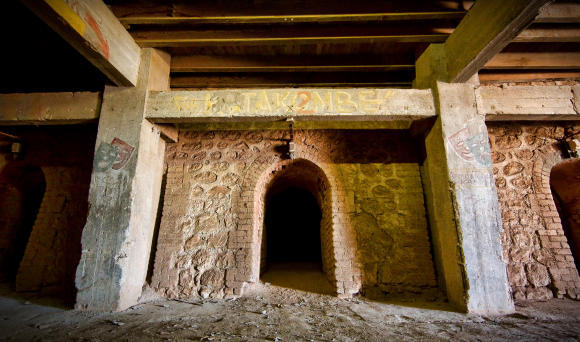

The inmates organized cultural activities in their fight against boredom and dehumanization. Feuchtwanger eloquently describes a cabaret club set up in the brick oven area of the camp, where they could mobilize their creativity and artistic talents. They called it the Catacomb, after a Berlin nightclub closed by Goebbels in the mid-1930s.

Feuchtwanger lived to write about his experiences because he managed to escape at the end of the summer of 1940, before the French began participating in the delivery of Jews to Nazi death camps. His wife Marta orchestrated his escape. At that time, he, along with other prisoners of Les Milles, had been moved to a makeshift tent camp near Nîmes. The prisoners were allowed to bathe every afternoon at a small river in the middle of the afternoon. This proved to be the perfect time of day to engineer an escape and smuggle him out disguised as an English woman and take him to Marseille.

There, Marta was assisted by the American vice consul in Marseille, Hiram Bingham IV, who was known for liberally issuing visas to help refugees, in defiance of State Department policy. Bingham arranged to have a picture of a grim and gaunt Feuchtwanger behind the barbed wires of the Milles Camp sent to America. Feuchtwanger’s publisher, Ben Huebsch of Viking Press, had friends show the picture to Eleanor Roosevelt, who made the president aware of the situation. An emergency visa was then issued, unofficially, in view of the American policy of neutrality during that period. Feuchtwanger was therefore added to a list of prominent artists and intellectuals, most wanted by Hitler and therefore in great jeopardy, to be rescued by the American Emergency Rescue Operations run by the American journalist Varian Fry.

From Marseille he undertook a dangerous journey through Spain and Portugal. Realizing that even in Portugal any delay to get on a boat to the United States could be fatal for a man wanted by the Nazis, Martha Sharp, a Unitarian minister’s wife, gave up her own berth on the Excalibur so that Feuchtwanger could sail immediately for New York City. His wife Marta obtained passage two weeks later.

Feuchtwanger was living in California and had published his memoir of his internment by the time Camp des Milles experienced its darkest days. In the summer of 1942, some 2,000 Jewish men, women and children rounded up in the southern France were interned at the Camp des Milles before deportation to Auschwitz, where they were exterminated. While the Germans never asked that children be deported, French minister Pierre Laval insisted that they be deported as well. At Les Milles this is given its full impact by the Serge Klarsfeld exhibition that commemorates the 11,400 Jewish children deported from the whole of France to Auschwitz between 1942 and 1944.

Feuchtwanger died in Los Angeles in 1958. After his death, his wife Marta willed their house Villa Aurora and his extensive personal library to the University of Southern California. Villa Aurora, a historic landmark, is now an artist residence.

Visiting the Camp des Milles

On September 10, 2012, exactly seventy years after the last train convoy left from Les Milles for the Auschwitz death camp, the Memorial-Site of the Camp des Milles was opened to the public. In 2015 UNESCO launched its new Chair for Education for Citizenship, Human Sciences and Shared Memories there. The Chair focuses on research and activism centered on the history of the Holocaust, citizenship and the prevention of genocide.

The historical section: A visit to the Memorial-Site of the Camp des Milles begins with a rich and compelling collection of displays, audiovisual pieces and illustrations in French and English dedicated to understanding the historical background to the threats that escalated across Europe between 1919 and 1939, to the individual destinies of those interned and to the history of France’s Vichy government. Displays document the general history of internment camps in France under the country’s Third Republic (i.e. prior to the summer of 1940) and under the Vichy regime. It recounts in detail the history of the Milles Camps where some 10,000 people of 38 nationalities were interned during the war. It also focuses on the perpetration of the Jewish genocide on a European scale and its implementation in Les Milles.

The remembrance section: The visit continues with the remembrance area, which includes the internment quarters of what had been a tile-making factory and the makeshift cabaret as described in Feuchtwanger’s memoir. Some of the artwork created by interned artists remains visible on the walls. In this section, the guide points out the windows from which women were willing to jump rather than suffer deportation and also indicates the places where some fortunate individuals managed to hide and survive.

The reflexive section: Based on a scientific analysis of the Holocaust, the Armenian genocide and the Tutsi genocide, this this third section provides an understanding of the mechanisms that can lead a democracy (both the system and the gathering of individuals within that system) towards a genocide and the capacity of individuals to resist. It also explores the human behavior mechanisms operating through racism, antisemitism and xenophobia.

The Wall of Righteous Acts concludes the visit to the Camp des Milles by showing the many different ways ordinary people can carry out acts of resistance in the context of genocide through examples of the past century.

Today young people remain an important target group for the memorial-site. Alain Chouraqui, president of The Milles Camp Foundation, has written that it is “not for the visitors, especially the young, to leave overwhelmed by the darkness of the persecutions, but rather that they become aware of vigilance and resistance.”

Practical information

Camp des Milles, 40 chemin de la Badesse, 13517 Aix-en-Provence. Tel. 04 42 39 17 11. Open 10am-7pm (no tickets sold after 6pm) daily except Jan. 1, May 1, Dec. 24, 25, 31. The memorial-site suggests counting on 2½ hours for a complete visit. Audio guides are available in English. For information about guided tours in English contact the camp directly. It can be cold in the internment quarters in winter – dress warmly.

The Devil in France: My Encounter with Him in the Summer of 1940 by Lion Feuchtwanger can be downloaded free of charge from the USC Libraries website. Further information about the writer and his life as an émigré in the United States can be found here.

Aix-en-Provence Tourist Office, 300 avenue Giuseppe Verdi, 13100 Aix-en-Provence.

Bus service (line 4) from the Rotonde near the Aix-en-Provence Tourist Office goes to the camp, whose station is called Gare des Milles.

© 2017

Wendy Dubreuil is a conference interpreter with a deep interest in human rights and discrimination issues.

Maybe it was political issues in the US that caused me to miss this article in the February edition; I am so glad I found it now. This is an interesting and important site–unknown to me until this insightful article. I want to explore more about both Feuchtwanger and Camp des Milles.