A couple visiting Paris from California discovers that their temporary home on Rue du Bac is surrounded by the ghosts of friends and acquaintances of democracy in America.

By Herbert H. Hoffman

In our younger years, long before we met, we had both been to Paris. We had seen the Eiffel Tower, Notre Dame Cathedral, the Champs Elysées, the Arc de Triomphe and other sights, most of them on the right bank of the Seine. We were now a couple, American tourists revisiting a city we had separately loved the first time. Friends had suggested that we might like the left bank this time.

We took their advice. We rented an apartment on rue du Bac, a street we didn’t know. “Our” house was at no. 40. The third floor leaned a little and the floor boards creaked at every step, making us walk as if we were at sea. It was the romantic milieu we had sought.

Rue de Bac is an old street, a former cattle-driving path leading to the ferry (le bac) across the Seine to what is now the western end of the Louvre. There is a bridge now, the Pont Royale, completed in 1689.

On our first evening in Paris we had dinner near the bridge at Le Terminus at no. 5 rue du Bac. The name of the restaurant refers to the nearby railroad station that was eventually transformed into the Orsay Museum. About 400 years ago, Charles d’Artagnan, the dashing captain of the King’s Mousquetaires, once rented rooms at no. 1 rue du Bac. The fusion of dates in a single location let us know that that certain parts of Paris run on a time table that differs from what we are used to at home in Southern California. It was just the beginning of our realization that Parisians store the memories of their notables on streets throughout the city, including a good many on rue du Bac.

The following day we discovered that at no. 44 we had another illustrious neighbor, so to speak, a ghost of more modern times, André Malraux whom people of our age group remember as DeGaulle’s minister of cultural affairs. Some of us know him for his novel La Condition Humaine, Prix Goncourt, 1933. He finished that book in a room just one door south from where we were billeted. He was a difficult neighbor, it seems, and some wit once said that he was one third genius, one third hard to follow and one third totally incomprehensible. He died in 1976 and is buried in the crypt of the Pantheon.

Another of De Gaulle’s ministers also once resided at no. 44. He was Maurice Couve de Murville. His portrait appeared on the cover of Time for February 1964 because he had important dealings with the United States. As France’s foreign minister, he had the unpleasant task of informing President Lyndon Johnson that the French government, convinced that America’s policies would lead to failure, could not lend support to the Vietnam enterprise. Unfortunately he was right, and we now had a glimpse of the ghost of Vietnam to add to our list. The poet Charles Baudelaire had set the scene for us when he wrote about the cité pleine de rêves, où le spectre, en plein jour, raccroche le passant, where ghosts by daylight tug the passer’s sleeves.

Our sleeves were tugged again a day later. Branching off rue du Bac across the street from our building is the short rue Montalembert, named for a writer and publicist of the 1830s who, incidentally, also once resided at our own address, no. 40 rue du Bac. As we followed this little street we came to rue Jacob where we stopped at no. 56, in front of a most important monument for a visitor with an interest in American history. It was here that Benjamin Franklin, John Jay and John Adams negotiated and, in 1783, signed the Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War and officially recognized the United States of America as an independent country. The building itself is not the original one but the site—am I too sentimental to say this?—remains the birthplace of the USA.

No Frenchman has been more celebrated in America than the Marquis de Lafayette, friend and trusted ally of General George Washington. There are at least twelve cities in the United States called Fayetteville. There are also three Lafayette townships, two Lafayette counties and one Lafayette parish. One of the Marquis’ homes was at no. 183 rue de Bourbon, several blocks around the corner from rue Jacob. It is a lieu de memoires that invited us to speculate what might have become of the American Colonies had France not been on our side. The French-American admiration goes both ways. We were happy to learn, for example, that the Marquis named his eldest son George Washington de Lafayette.

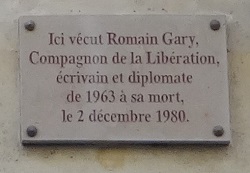

Americans have many friends whose spirits still hover over or near rue du Bac. We promptly located another: the writer Romain Gary, who resided at no. 108. He won the Prix Goncourt, a prestigious literary prize, twice, for The Roots of Heaven and The Life Before Us, respectively. Apart from being an essayist, soldier, politician, diplomat, pilot and secretary of the French delegation to the United Nations, he was also a friend, almost an American himself, working as a screenwriter in Hollywood and later as consul of France in Los Angeles. He died in 1980. His ashes float in the Mediterranean.

Americans have many friends whose spirits still hover over or near rue du Bac. We promptly located another: the writer Romain Gary, who resided at no. 108. He won the Prix Goncourt, a prestigious literary prize, twice, for The Roots of Heaven and The Life Before Us, respectively. Apart from being an essayist, soldier, politician, diplomat, pilot and secretary of the French delegation to the United Nations, he was also a friend, almost an American himself, working as a screenwriter in Hollywood and later as consul of France in Los Angeles. He died in 1980. His ashes float in the Mediterranean.

The American artist James Whistler lived at no. 110 from 1892 to 1901. He died in London in 1903 and is buried across the channel, but his mother—at least her stern portrait officially titled “Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1” (1871)—remains in Paris and is now a stone’s throw from rue du Bac, in the Orsay Museum.

The writer François René de Chateaubriand was still a very young man in Franklin’s day. He was astute enough, however, to have observed that in the days before the French Revolution turned ugly the ordinary people of Paris were enthusiastic about the Americans’ struggle for independence (from the King of England, that is). In the street, if not in the royal palace, “le suprême bon ton était d’être américain“, the coolest thing was to be American, Chateaubriand wrote in his memoires. He traveled to America and met General Washington. He describes this visit in great detail, finishing his account by calling Washington “le soldat citoyen, libérateur d’un monde,” citizen soldier and liberator of a world. He confessed in his memoires how happy he was that the General received him and that he has felt a certain excitement about the encounter all his life: “je m’en suis senti échauffé le reste de ma vie“. Chateaubriand remained a lifelong friend of America and years later remarked with satisfaction that “la république de Washington subsiste; l’empire de Bonaparte est détruit,” Washington’s republic lives; Napoleon’s empire is dead. We were truly surprised to find such a good friend at no. 120 rue du Bac. Across the street in a little park there’s a sculpture, a bust really, of this remarkable man. His remains are not in the Pantheon. They are in St. Malo where this stubborn writer and diplomat from Brittany had wished to be buried.

The writer François René de Chateaubriand was still a very young man in Franklin’s day. He was astute enough, however, to have observed that in the days before the French Revolution turned ugly the ordinary people of Paris were enthusiastic about the Americans’ struggle for independence (from the King of England, that is). In the street, if not in the royal palace, “le suprême bon ton était d’être américain“, the coolest thing was to be American, Chateaubriand wrote in his memoires. He traveled to America and met General Washington. He describes this visit in great detail, finishing his account by calling Washington “le soldat citoyen, libérateur d’un monde,” citizen soldier and liberator of a world. He confessed in his memoires how happy he was that the General received him and that he has felt a certain excitement about the encounter all his life: “je m’en suis senti échauffé le reste de ma vie“. Chateaubriand remained a lifelong friend of America and years later remarked with satisfaction that “la république de Washington subsiste; l’empire de Bonaparte est détruit,” Washington’s republic lives; Napoleon’s empire is dead. We were truly surprised to find such a good friend at no. 120 rue du Bac. Across the street in a little park there’s a sculpture, a bust really, of this remarkable man. His remains are not in the Pantheon. They are in St. Malo where this stubborn writer and diplomat from Brittany had wished to be buried.

As an aside it’s worth noting that Chateaubriand’s longtime friend Madame Récamier was with him when he died. That was in 1848. She died a year later. She is known to many of us because Jacques-Louis David portrayed her in a thin white something reclining on a two-headed couch. We now call that sort of sofa a Récamier. The picture hangs in the Louvre.

One of the cross streets of rue du Bac is rue de Varenne. There, at no. 50, stands the Hôtel Galliffet, where, in 1797, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand was installed as foreign minister during the Directoire period of the new French Republic. (It is now the Italian Cultural Institute.) It is no exaggeration to say that Talleyrand was the most ingenious politician and statesman of the French revolutionary period and beyond. It is said that First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte was a guest here at one of his parties. By 1803 Talleyrand was Napoleon’s adviser, an appointment that had incalculable consequences for the new United States. Napoleon had plans to expand French possessions in the Americas. President Jefferson was aware of these plans and feared that the United States, then a small country, might lose docking privileges in the formerly Spanish, now French harbor of New Orleans. He sent envoys to negotiate lease terms. Napoleon’s plans had changed, however, and Talleyrand, his negotiator, suggested that the President just buy New Orleans outright, and the rest of Louisiana as well. All American school children know about the Louisiana Purchase which doubled the territory of the United States. It was news to us that we have to thank Monsieur de Talleyrand for that.

One of the cross streets of rue du Bac is rue de Varenne. There, at no. 50, stands the Hôtel Galliffet, where, in 1797, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand was installed as foreign minister during the Directoire period of the new French Republic. (It is now the Italian Cultural Institute.) It is no exaggeration to say that Talleyrand was the most ingenious politician and statesman of the French revolutionary period and beyond. It is said that First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte was a guest here at one of his parties. By 1803 Talleyrand was Napoleon’s adviser, an appointment that had incalculable consequences for the new United States. Napoleon had plans to expand French possessions in the Americas. President Jefferson was aware of these plans and feared that the United States, then a small country, might lose docking privileges in the formerly Spanish, now French harbor of New Orleans. He sent envoys to negotiate lease terms. Napoleon’s plans had changed, however, and Talleyrand, his negotiator, suggested that the President just buy New Orleans outright, and the rest of Louisiana as well. All American school children know about the Louisiana Purchase which doubled the territory of the United States. It was news to us that we have to thank Monsieur de Talleyrand for that.

Another important person was at that party in 1797, Madame de Staël. She was a champion of liberty, freedom of speech and democracy, a prolific writer, critic and mover of ideas. She met or corresponded with everybody who was anybody, anywhere, from Auguste Comte, Lafayette and Lord Byron to Emerson, Goethe and Pushkin. Politically she was opposed to Napoleon I, Emperor of the French. He exiled her because the dislike was mutual. By 1815 Napoleon was out, however, but Madame was not. She had good judgement and saw the world clearly. Some wit suggested that with Napoleon now gone there were only three powers left to save Europe: England, Russia and Mme de Staël. Such was the woman who had her salon at no. 94 rue du Bac, an influential woman who had nothing but good to say about America. “You are the advanced guard of the human race,” she is reported to have said. “You have the fortune of the world.”

At the Seine end of rue du Bac the river road was once called quai des Théatines, now quai Voltaire. There, at no. 27, another illustrious man of letters, Jean Arouet, dit Voltaire, died in the home of his friend, the Marquis de Villette. He did not live to witness the signing of the Treaty of Paris, but he knew Franklin and apparently liked him enough because it is said that he referred to the struggling colonies as “Franklin’s New World.” Voltaire, incidentally, once suggested that it was the duty of all men to examine their hearts and ask if religion should not be charitable rather than barbaric. The question is still open.

Before the great renovation projects of Baron Haussmann in the 1850s and 1860s, rue du Bac was connected to rue St. Dominique. Alexis de Tocqueville was born in 1805 at no. 77 rue St. Dominique, above what is now an Irish pub. In 1831 the United States was still somewhat of a mystery. The French government was eager to learn how things were done in this new republic. They sent a young de Tocqueville to find out. His two-volume report became a classic, known to us as “Democracy in America.”

The spirit of Charles Louis, Baron de Montesquieu caught up with us on rue St. Dominique, mainly because my book discussion group had recently studied his De l’esprit des lois. He is another important Frenchman for Americans because his ideas were widely read in the second half of the 18th century and were in part responsible for the way the Constitution of the United States was conceived. He did not live to see what he had helped create. He died in 1755 on a visit to Paris, probably at a friend’s house at no. 16 rue St. Dominique.

Antoine-Nicholas de Condorcet lived at no. 6 rue St. Dominique. He had much to say about the American Revolution. Shortly before his death in 1794 he wrote a treatise outlining how its development could ultimately benefit the world. His particular concern was an extensive bill of rights that would go farther than the Constitution did at that time. He foresaw the need to abolish slavery, for example. Our forefathers should have listened to him. Without his encouragement it took us another seventy years to accomplish that. Tragically, he did not survive the French Revolution.

America has still another friend whose memory lives on in Paris, the poet Charles Baudelaire. While it is difficult to say where in Paris Baudelaire lived—he lived in many different places—it appears certain that he once lived at no. 21 rue du Bac, in a house that is still there, a house with a huge stone portico spanning an extra wide wooden portal. “J’ai longtemps habité sous de vastes portiques...” he wrote in La Vie Anterieure, which increases the probability that it was this house.

A decade or so after de Tocqueville’s voyage, an American poet burst upon the Parisian scene, Edgar Allan Poe. Some say that there is a melancholic string in the French soul and that Poe’s somber moods made that string vibrate. Baudelaire and Poe never met but they were kindred spirits. Here is a stanza from Baudelaire’s poem Spleen, translated by Kenneth O. Hanson:

When the low heavy sky weighs like a lid

Upon the spirit aching for the light

And all the wide horizon’s hid

By a black day sadder than any night…

“…un jour noir plus triste que les nuits” – a black day sadder than any night? Well then, how about “Once upon a midnight dreary”?

If the French understood Baudelaire, how could they not love Poe? It is not hard to see why Baudelaire felt compelled to translate The Raven, and everything else Poe wrote, into French. To this day, it is said, Poe is better known in France than in America. How comforting to know that we have cultural as well as political ties across the ocean. And the story does not end here. Messrs. Harper Brothers, Poe’s publishers, commissioned the well-known French painter Gustave Doré to illustrate The Raven, the original English language edition, with twenty-five engravings. Over the years these illustrations have become almost as important and as gripping as Poe’s words. And the work has endured. Doré, it turned out, is another spirit floating over the neighborhood. The house where he lived with his mother was no. 73 rue St.Dominique, across the street from the Tocquevilles’.

Who would have thought that America has so many friends among the ghosts of this old neighborhood?

© 2016

Herb Hoffman and Joan Preston visit France from their home in Southern California as often as possible. They enjoy walking the streets and stumbling upon places that hint at a story which Herb then puts into words.

Hi. My wife and I also live in Southern California. We have visited Paris many times but not for years. We are planning a return this April (COVID permitting.). Unlike other visits we plan on settling down for our stay on the left bank. We are reviewing our French and our live for Paris. Many years ago, we read a novel about a young woman who traveled from NYC to Paris. She has a place on the rue du bac. The novel creates such a wonderful feel for this part of Paris. I have searched my brain and the Internet exhaustively but cannot come up with the name. We would love to read it again. Does this ring any bells?