It’s understandable that so many people in France wanted to buy a copy of the January 14, 2015 issue—the survivor issue—of Charlie Hebdo as soon as it went on sale. One can come up with so many reasons to buy it: to support the publication; to show support for freedom of expression or for the “values of the republic”; to feel that one is thumbing one’s nose at extremism; to own a memento of a historical event; to acknowledge to oneself or to others “I am/was there”; to judge for oneself how daring, irreverent or irresponsible the publication is; to feel as Charlie as one did over the weekend; to sell it on ebay, and other reasons.

I might have bought a copy myself, but the first batch was out by the time I left the apartment, and a friend soon sent me the complete pdf.

One couldn’t avoid seeing the cover of the issue in France, whether at the newsstand or on TV or, without any particular search, on the internet. How strange, how revealing of cultural differences it was then to be an American in Paris surrounded by images of the cover of Charlie Hebdo, and then to see that American news sources, while reporting heavily on the subject, were self-censoring or actively avoiding showing the cover, while in some countries mobs were called to violence to denounce the image.

The prominence and the significance of the news of the publication of the first survivor issue of Charlie Hebdo made January 14 feel like the winter, newspaper version of May 1, when it’s customary for French to give each other a sprig of lily of the valley as a sign of friendship, love, good luck or social justice or in the name of tradition or obligation. (On the news we saw that for those who opposed the right to publish a caricature of the prophet it was a day of rage.)

The attack at Hyper Cacher may have come after the attack on Charlie Hebdo had already brought us out onto the street, but it was part and parcel of the events of January 7-9. So within all the earnestness and giddiness surrounding the sale of Charlie Hebdo, the day’s lily of the valley, news outlets in France and abroad were also showing long lines of people buying kosher food. “After all,” a young blond woman said as her 4-year-old held up a can of kosher pastrami, “just as few people buying the post-assassination Charlie Hebdo issue bought it for the contents, one needn’t buy kosher food for the blessing.” There was a great sense that, beyond the rally of January 11, on an otherwise typical work day, millions of people would continue to affirm the values of the republic by honoring both the rights and security of those who would mock religious dogma and institutions and their perverse effects, on the one hand, and the rights and security of those who wish to eat or otherwise pray in the private sphere according to religious dogma, on the other.

Well, no, actually. I made that up. No one spoke of buying kosher food to also show their support for the freedoms that the terrorists wished to eradicate.

Was it so difficult to support both secularism and the peaceful practice or non-practice of religion? Or did one feel a need to choose sides among victims and what they represent or are thought to represent?

I would think not. As Charlie Hebdo’s own editorial of January 14 states: “No, in this massacre, there are no deaths less injust than others” (Non, dans ce massacre, il n’y a pas de morts moins injuste que d’autres).

Having read the survivor issue of Charlie Hebdo, I also wanted to buy some kosher food. I needed to go shopping anyway: a journalist friend (religious affiliation, if any, unknown) was coming for dinner.

There are no specific kosher shops in my neighborhood so I went looking at a local grocery store. I couldn’t find a kosher section there, and there was no kosher food in the store’s “World” section.

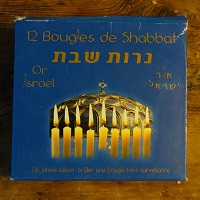

The “World” section did, however, have Sabbath candles (bottom shelf, blue box in the photo). I thought this odd given that there’s a candle section on the opposite side of the store. I then realized that it wasn’t so odd since they were next to Italian rice and pasta even though the store has large rice and pasta sections. The logic is that a customer would go to the “World” section to look not for rice or pasta but for Italian goods. The Sabbath candles, made in Israel, are therefore considered at this grocery store as national rather than religious items, as though one might want to serve Italian pasta, Spanish olives and Chinese tea light by Israeli candles.

The French have been debating whether Jews form a “nation apart” or not since at least the Revolution. In December 1789, the National Assembly inconclusively debated the issue of the rights of Jews in a post-despotic France, with two main arguments arising: one said that, given the chance, Jews can be assimilated with and citizens of the larger society, the other said that Jews are bound to be a nation apart and so cannot be citizens of the nation of France.

French Jews were given the full rights of citizenship (emancipated) in two blocks: in January 1790 by a law largely covering Sephardic Jews of southwest France and the area around Avignon, and in September 1791 by a law covering Ashkenazic Jews (mostly in Alsace and Lorraine) and others.

The debate of the place of Jews in French society nevertheless continued, mostly in attempts (at times successful) to reduce the rights of Jews. The debate can still be heard, and not just among gentiles. In fact, Israeli Prime Minister Natanyahu weighed in in favor of nationhood at his speech at the Great Synagogue of Paris on January 11, when he invited Jews to come “home” to the nation he leads. To which some congregants responded by singing their national anthem, La Marseillaise.

I bought the Sabbath candle. I was pleased with the symbolism of the Sabbath itself being a Jewish hebdo (hebdo means weekly) and with the thought that I would light the table with them that Wednesday evening.

When I mentioned to my guest that since I was unable to buy Charlie Hebdo I went looking for kosher food, he called my logic amalgame (amalgam). If there is one French word that a foreigner should retain from recent events it is amalgame. The term refers to the mixing of two distinct ideas, events or situations that are brought together in order to deliberately creating confusion, typically in order to discredit an individual or group and/or to exploit an event to demonstrate one’s point of view for political advantage or to rationalize broad condemnation or hatred. Saying C’est de l’amalgame (That’s an amalgam) is a way of crying intellectual foul against someone’s argument. It’s often heard in response to someone who says that all Muslims must respond for an assassination in the name of Islam or that the relationship between Israel and Palestinians is that of all Jews and all Arabs.

Though equating purchasing kosher food with purchasing the survivor edition of Charlie Hebdo required a shift in the reflex to want the publication (and freedom of the presss, etc.) to win the day, I thought my friend wrong to call their association an amalgam. I thought it misguided to insist that this day belonged to Charlie Hebdo alone, as though saying “Je suis Charlie” the other day meant that we had all agreed that we found Charlie Hebdo funny and pertinent and worth buying, that we had committed a republican sin by not subscribing earlier. The amalgam between the creators of satire and the consumers of kosher food, I countered, was thrust upon us by the terrorists.

But they aren’t wrong to lump together the targets of their distain. All of them—satirists, Jews, police and many others—are deserving of protection. To now remember only half of the split screen of the double assaults by security forces on January 9 would be to refuse the basic facts of what had occurred or to believe that in this massacre there were some deaths more unjust than others. Some amalgams must be made. And lucky us that we can enjoy the symbolic value of Charlie Hebdo and kosher food on the same day, even if we find them both tasteless.

My friend had had a rough week preparing his own weekly magazine for publication and neither of us was up for punditry that evening. We dropped the subject as I opened the bottle of wine that he’d brought, an easy-going Côtes du Roussillon whose meaning I didn’t question.

I realized that I didn’t have any candle holders for the Sabbath candles. Then I realized that I did: cadavers, as the French call empty bottles, from a recent craft beer tasting.

I lit several candles.

I served a salad (endives, feta, sundried tomatoes, grilled peppers), followed by fresh pasta with eggplant and ricotta, not from the “World” section but from an Italian shop. Greek yoghurt, chocolate and clementines for dessert. Calvados.

The meal was mostly Italian but with a nod to what I already had in my refrigerator, along with a domestic wine imported by my guest and brandy from a war tour in Normandy—an delicious well-accompanied amalgam of sorts, with candles and cadavers to spare.

© 2015, Gary Lee Kraut