Vel d’Hiv Memorial (viewed from behind) commemorating the round-up of over 13,000 Jewish on July 16 and 17, 1942.

Jewish quarters come and go, but anti-Semitism never goes out of fashion. Most recently in France—we are in 2014—there’s been a growing attraction (patent yet limited) of the “quenelle,” a down-turned Nazi salute now understood by most to be an anti-Semitic, anti-establishment gesture. It has gained favor among individuals and groups who believe that Jewish concerns, interests and history get too much airplay, in the way that some in France and elsewhere will unify in their antagonism against homosexuals, gypsies or others.

The Deportation Memorial

Jews, homosexuals, gypsies, political opponents and others were among the 200, 000 men, women and children deported from France to Nazi concentration camps between 1940 and 1944 who did not return. The French Deportation Memorial that honors their memory lies at the eastern tip of Ile de la Cité, behind Notre-Dame Cathedral.

At the back of quiet little park, steep stairs lead to a high-walled triangular courtyard where the Seine can be seen flowing toward barbed iron. A first-time visitor might think that itself is the monument before noticing a narrow passage formed by two blocks of stone leading into the memorial crypt.

At the back of quiet little park, steep stairs lead to a high-walled triangular courtyard where the Seine can be seen flowing toward barbed iron. A first-time visitor might think that itself is the monument before noticing a narrow passage formed by two blocks of stone leading into the memorial crypt.

Inaugurated by President Charles de Gaulle in 1962, the memorial crypt contains the Tomb of the Unknown Deportee. The remains placed in the tomb are those of an individual who died in the concentration camp of Neustadt. A long alley containing 200,000 points of light extends beyond the tomb. Triangular urns inscribed with the names of concentration camps contain earth from the camps and ashes from their crematoria. Lines of poetry inscribed on the walls speak of pain, loss and tragedy. The entrance is barred to the cells to either side the alley. We peer into these cells unable to see the dark corners, unable to fathom what suffering they might hold.

An annual ceremony is held here on the last Sunday in April. That has, since 1954, been designated as the National Day of Memory of the Martyrs and Heroes of the Deportation, which is close to the date of the Hebrew calendar on which Holocaust Remembrance Day, Yom HaShoah, is commemorated.

The Shoah Memorial and the Holocaust Center

Of the 200,000 individuals memorialized at the Deportation Memorial, about 77,000 were born Jewish, and they were specifically targeted to be exterminated because of that. The majority of those Jews were killed in Auschwitz and Birkenau. Several thousand died in internment camps and some thousand others were otherwise executed or killed in France. The memorial to their memory is in the Marais, a large district (broadly the 3rd and 4th arrondissements) that had sizeable Jewish population at the outbreak of the war. The Shoah Memorial/Holocaust Center building is situated within a 10-minute walk of the Deportation Memorial to one side and rue des Rosiers to the other.

Roundups and Deportations

Following Germany’s defeat of France and the Armistice of June 22, 1940, the Germans occupied the northern half of France and a wide swatch down the country’s Atlantic coast. With Paris occupied, the French government, having originally decamped to Bordeaux, made the spa town of Vichy its headquarter. There, on July 10, 1940 Marshal Philippe Pétain, a hero of WWI, was voted full governmental power, hence reference to the French government from then until the Liberation of France in 1944 as the Vichy government.

An estimated 270,000 to 300,000 Jews were living in France in the late 1930s. Within several months after France’s armistice with Germany, the policies of the German occupiers and new French laws led to Jews being progressively excluded from professional life and dispossessed of property. Jews, defined by French officials as individuals with at least two Jewish grandparents, were required to register with the local police, constituting files that would eventually be used to round up Jews for deportation.

In collaboration with Germans and on their own, the French government along with local and state French police began rounding up Jews in 1941, first primarily foreign Jews then increasingly French Jewish men. Jews were required to wear a yellow star as of June 1942. The massive and all-inclusive round-ups in the Occupied Zone would follow.

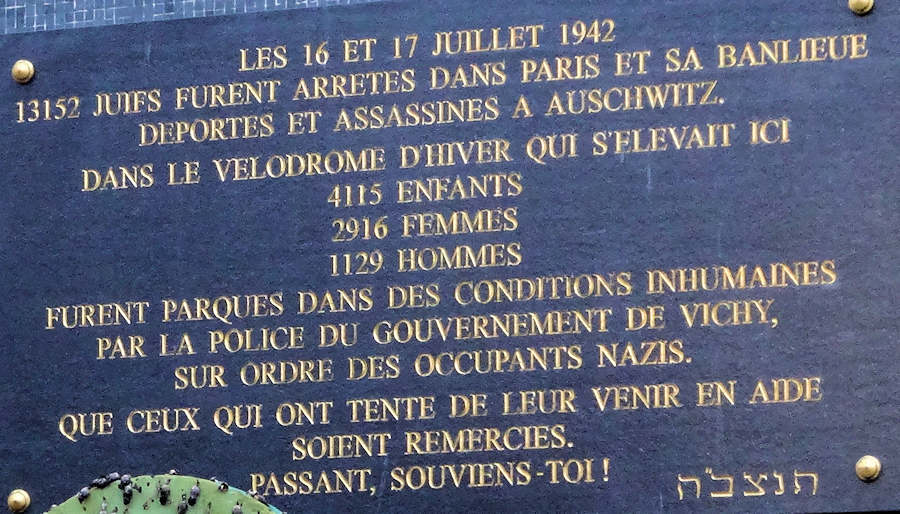

During the mass round-up (rafle in French) of July 16-17, 1942, 13,152 Jews were arrested in Paris and the Paris region. The event was exceptional not only for the number of Jews that were arrested in a single well-organized sweep but for also the fact that it embodied a clear shift in policy to the deportation of women and children along with men. Many of those arrested were corralled at the winter cycling stadium—the Vélodrome d’Hiver, commonly known as the Vél d’Hiv—that then stood just beyond the Eiffel Tower. From there they were moved to the transit camp at Drancy, northeast of the city, and then by train to Auschwitz.

Though not the only round-ups of the war period in France, those of July 1942 have come to represent the injustice and horrors of deportations throughout that period in France.

In 1995, at the site of the Vélodrome, President Jacques Chirac officially recognized on behalf of the nation France’s responsibility, under the authority of the Vichy Government and in collaboration with the Germans occupying the country, in the deportation of French Jews.

While the sculptural group shown above has been placed near the river, a memorial stands by the site of the former velodrome at 8 boulevard de Grenelle.

The Wall of the Righteous

Of the 270,000-300,000 Jews in France prior to the start of the war, nearly 75% survived by their own means, through the help of Jewish resistance organizations and/or through the assistance of non-Jewish French, through efforts both individual and collective.

For a variety of reasons, a larger percentage of French Jews escaped the Shoah than Jews from most other European countries. That partially explains why France now has the largest Jewish population in Western Europe. (Another reason for its size is the many Jews who arrived from Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco as those countries gained independence from France in the 1950s and 1960s.)

Righteous Among the Nations is a title granted since 1963 by the State of Israel via the Memorial Museum of Yad Vashem in Jerusalem to non-Jewish men and women who helped save Jews from persecution during the war. The names of over 3300 Righteous, whether French or acting in France, are inscribed in bronze plaques along the alley, now named Allée des Justes (Alley of the Righteous), that borders the north side of the memorial. Inaugurated in 2006, the Wall of the Righteous also contains the name of the village of Chambon-sur-Lignon, a largely Protestant village whose religious leaders and villagers, some of whom are individually designated as Righteous, helped save numerous Jews. French Protestants had known periods of tremendous intolerance and murder at the hands of the Catholic majority and nobility from the 16th to the 18th centuries.

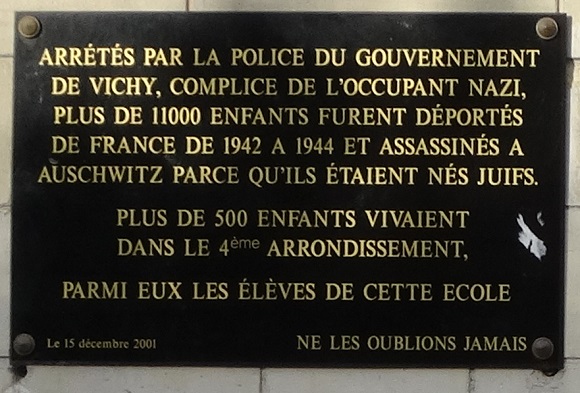

On the opposite side of the Allée des Justes can be seen a plaque indicating that more than 11,000 Jewish children were sent to the camps from France, including more than 500 from this, the 4th, arrondissement. Such plaques are now found on schools in districts throughout Paris where Jews lived. Some 6100 of those children lived in Paris. A sign facing the playground in Square du Temple, a park on the northern edge of the Marais, lists the names of 87 children (les tout-petits) from the 3rd arrondissement who weren’t yet old enough to attend school before being sent to the camps.

Entrance to the Shoah Memorial

Ten years after his speech at the site of the Vél d’Hiv, President Chirac inaugurated the Shoah Memorial and Holocaust Center on January 27, 2005, on the Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust and for the Prevention of Crimes against Humanity, marking that year the sixtieth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

Security here is attentive, humorless and direct, as at the entrance to other major Jewish sights, notably the Great Synagogue on rue de la Victoire (9th arrondissement), but one can nevertheless freely enter the memorial (if without a weapon), whereas the synagogue requires prior arrangement for those who aren’t normally affiliated with it.

The names of death camps are written on a circular memorial in the courtyard, above the memorial crypt. Along the nearby wall seven bas-reliefs (1982) by the sculptor Arbit Blatas symbolize the camps. Text on the façade of the building written in Hebrew from poet Zalman Schnoeur’s adaptation of a line from Deuteronomy 25:17 is translated by the center as follows: “Remember what Amalek did unto our Generation exterminating 600 myriad bodies and souls, in the absence of war.”

Below that is written in French the words of Justin Godard, former government minister, Honorary President of the Committee for the Unknown Jewish Martyr: “Before the unknown Jewish martyr, incline your head in piety and respect for all the martyrs; incline your thoughts to accompany them along their path of sorrow. They will lead you to the highest pinnacle of justice and truth.”

History of the Shoah Memorial

The Shoah Memorial and the Holocaust Center form a single entity whose mission is “understanding the past to illuminate the future.” The building combines a museum, a documentation center and reading room, France’s largest (by number of titles) physical bookstore on the subject of the Holocaust, an auditorium for screenings, symposia, debates and presentations, offices and a memorial crypt. Though the building, as a Holocaust center, was inaugurated in 2005, the memorial itself had already existed.

Already in 1943 there was awareness among some Jews in France that evidence and testimony of their persecution would be necessary for the time when justice would be demanded. In April of that year Isaac Schneersohn invited 40 militant leaders of the various political factions in the Jewish community to his home in Grenoble, in the unoccupied zone, to set up the Center for Contemporary Jewish Documentation. But in September of that year the Germans entered into the unoccupied zone (referred to as the Free Zone by the Vichy government), causing Schneersohn and others to go underground as part of the Resistance. There, efforts continued to collect secret archives, including those held by the Vichy government and by the Gestapo in France.

After the war the CDJC began classifying these archives and established a publishing house to publish books and journals about the Shoah. The CDJC was soon called upon by the French government to provide evidence for the Nuremberg Trials.

Still under Schneersohn, the CDJC in 1951 sought to create a memorial to the victims of the Shoah and eventually obtained this plot of land owned by the City of Paris. Schneersohn passed away in 1969.

The Wall of Names

An estimated 78,000-80,000 Jewish men, women and children were deported from France between 1942 and 1944. Of them, some 76-77,000 did not return. (The round numbers in this article are approximate as figures vary among the most serious sources. Those given in this article are generally those presented at the center.) Past the security box at the entrance from the street, one approaches the building through the narrow passage between walls inscribed with the names and dates of birth of these individuals, listed alphabetically by year in which they were deported.

The Memorial Crypt

The building housing The Memorial to the Unknown Jewish Martyr was inaugurated in October 1956, three years after the laying of its cornerstone, and in February 1957 ashes of victims from Auschwitz-Birkenau, Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Sobibor, Treblinka, Mauthausen and from the Warsaw Ghetto, placed in earth from Israel, were buried in the memorial crypt.

A Biblical quote in Hebrew on the back wall of the crypt reads: “Look and see if there is any sorrow like my sorrow. Young and old, our sons and daughters were cut down by the sword.”

A map of the Warsaw Ghetto and an actual door from the Ghetto are now on the opposite wall. Off to the side, behind Plexiglas, are the “Jewish Files,” the index cards created between 1941 and 1944 under orders of the Vichy government and the will of the police department of the Paris region indicating the identification of Jews. These are the files that were used by French police in complicity with the Nazi occupier to know the identity and address of Jews to be rounded up for eventual deportation. Though present here for their association with the memorial, the files belong to the National Archives of France.

The Permanent Exhibition

The Shoah Memorial was officially listed on the register of historic buildings in 1991. But it soon became evident that of the need to enlarge the building and bring the CDJC and the Shoah Memorial together a single entity. A major transformation of the building led to its reopening in early 2005. The facades and the crypt of the original building were integrated into the new structure.

Other than to coming pay homage to the memory of victims of the Shoah, the permanent exhibition in the sub-basement museum is the most instructive aspect of the memorial and center for first-time visitors. Through photographs, texts, documents, films and recordings, the exhibition provides an excellent overview of the history of anti-Semitism in Europe and the events of the war period, followed by evidence and testimony gathered during the post-war period. While the films and recordings are in French only, the texts are in both French and English.

The center’s board of directors includes a number of well-known Jewish figures in French political, intellectual and economic life, currently among them Eric de Rothschild (president), Robert Badinter, chief rabbi Gilles Bernheim, Alain Finkielkraut, Serge Klarsfeld and Simone Veil. Among the memorial’s partners are the City of Paris, the Paris region (Ile de France), the Ministry of Education and the French train company SNCF.

© 2014, Gary Lee Kraut

The Shoah Memorial, 17 rue Geoffroy-l’Asnier, 4th arr. Tel. 01 42 77 44 72. Metro Saint-Paul or Pont-Marie. Open Sunday to Friday 10am-6pm, until 10pm on Thursday. Closed for certain Jewish holidays as well as Jan. 1 and Dec. 25. Admission is free except for the auditorium and some educational activities. Free guided tours for individuals are given Sundays at 3pm in French and the second Sunday of each month in English.

The 7000+ titles available through the center’s bookshop are listed online at www.librairie-memorialdelashoah.org.

The Museum of Jewish Art and History, is also in the Marais at 71 rue du Temple, 3rd arrondissement. Metro Rambuteau or Hôtel de Ville. Open Monday to Friday 11am-6pm, Sunday 10am-6pm. Exhibitions open until 9pm on Wednesday. A 15-minute walk from the Shoah Memorial and also in the Marais, this museum is housed in a 17th-century mansion called the Hôtel de Saint-Aignan, a building occupied in 1942 by number of Jews, 13 of which died in the camps. The permanent collection shows glimpses of Jewish life in France through the centuries and mounts notable temporary exhibitions.

Related articles on France Revisited:

– Paul Niedermann: Interview with a Holocaust Survivor and Witness in France

– In Search of a Jewish Quarter: Rue des Rosiers and the Jewish Food Court of Paris

The Museum of Jewish Art and History’s permanent exhibit is about the longevity of Jewish presence in France, with ancient tombstones, the old Torahs and printed material from the beginning of printing. There’s a good section of the exhibit on traditional dress from French North Africa and a good section on the Dreyfus affair. In the middle of the staircase in the exhibition area, there is a research center. If the interest is the holocaust, then, yes, the Holocaust Center is the place to go, but for a more general view, this museum is good.

The building has gone through many transformations. It started out as a “hôtel particulier”, but became the “mairie” for the 3rd arrondissment after the revolution. Then, it became a factory building, with shops and workshops on the ground level and there were workers’ quarters built on top of the original building. In the restoration, those were taken down, of course.

The stone staircase near the entrance was restored to the original plans by “compagnons du devoir” with stone from the quarry used originally. If you take a look at the stone, try to figure out which are new and which are original.

No comment can express my revulsion of the anti-Semitism revealed by the atrocities of the Third Reich.

I have visited most of the sites described above.

Rest in peace.

Beautiful and incredibly important, the work that has been done to preserve and share the story of this terrible period of human history, and to respect and honor the victims of violence. And this is a beautiful article documenting that work. Thank you for writing it.

Is there a list online of the names?

You should contact the memorial directly to inquire about access to their database: http://www.memorialdelashoah.org/

Many of my relatives, alas, are listed on this Memorial.

I will be looking for the names of my grandparents ànd my father’s sister when i visit there in December. Visiting the Vel d’hiv and Paying my respect is all that there is left that i can do.

Last September, I visited Paris. It was my first time leaving the United States. On a walk with my girlfriend from Rue de la Convention to the Eiffel Tower, I was idly playing Pokémon Go. One of the Pokéstops was a glass mosaic on the front of a school. I was interested in this, so I wandered over to it. Once there, I looked up and saw a plaque like the one above. Curious and wanting to exercise my skills at reading French, I started reading it, thinking it little more than another historical marker.

As I read, my heart began to sink. I realized for the first time that I was actually standing on the ground where this thing I had only read about in books and seen in documentaries had actually happened. I tried and failed to fight back tears as I translated and read out loud, knowing children were ripped away from their rightful homes and schools where they were supposed to be safe, and carted off to die. And it had happened right where I stood.

On another trip around the city, I found yet another space dedicated to Holocaust victims. A wall filled with names that would take a day to read listed only 15 children who had escaped.

While the vast majority of my first trip out of the US was incredible and enjoyable, I will forever hold close the solemnity and gravity of these spaces. Ne les oublions jamais!

I would like to make a contribution in honor of my family, Victims of the Shoah, deported from Paris to Drancy, and then to Auschwitz, in July 1942. Their names are Jacques ( Yankel) and Esther (Sciare) Hazenberg.