When visiting rue des Rosiers in the Marais are travelers correct in thinking that they are actually visiting “the Jewish quarter”? Is the presence of Semitic fast food and a few Judaica shops a reflection of a vibrant local community, of successful ethnic marketing or of a combination of the two? Let’s take a look at what’s there.

* * *

Adidas, Kookai, Minelli, Annick Goutal, Fred Perry, The Kooples, Kusmi Tea. Does that sound like the making of “the Jewish Quarter” to you? It doesn’t to me either, but those are among the signs—along with “falafel, 5€50”—that one now finds on rue des Rosiers, the 1000-foot long street in the Marais that was once a main artery of Yiddishkeit in Paris.

Even well into the 1970s a visitor, few as they were, might have peered into storefront or observed local residents gathering in the street or returning from work and sensed a neighborhood, a community, whose lifestyle and traditions were visible, alive and collective, whether Ashkenazic, Sephardic or Parisian.

Now, however, the tradition most followed on rue des Rosiers is that of a shopping mall, with a Jewish-theme food court to one end and familiar international clothing brands to the other. It can be hard to see the history for the falafels.

Jews were known to have lived on the City Island in the 6th century and later on the Left Bank, and records indicate their presence in the Marais by the 13th century. Nevertheless, due to successive expulsions and limitations on the activities of Jews, notably in the 14th century, there were in fact relatively few Jews in Paris at all between the 15th century and 18th century, when Jews began trickling back. Nevertheless, due to successive expulsions and limitations on the activities of Jews, notably in the 14th century, there were in fact relatively few Jews in Paris at all between the 15th century and 18th century, when Jews began trickling back. Still, it’s unlikely that there were any Jews in the Marais when, in 1791, during the Revolution, France became the first European country to grand Jews full rights of citizenship. By the early 1800s Jewish presence in the Marais was well established. Jewish arrivals in the quarter, and throughout Paris, took on greater amplitude in the second half of the 19th century, with large movement of Jews from Alsace and Lorraine, where more than half of the Jews of France had lived. Others arrived from Eastern Europe (Romania, Austria-Hungary, Russia), particularly between 1881 and 1914, in the same pogrom-fleeing waves that reached American shores, and Jews continued to arrive in the Paris region into the 1930s.

Jews were known to have lived on the City Island in the 6th century and later on the Left Bank, and records indicate their presence in the Marais by the 13th century. Nevertheless, due to successive expulsions and limitations on the activities of Jews, notably in the 14th century, there were in fact relatively few Jews in Paris at all between the 15th century and 18th century, when Jews began trickling back. Nevertheless, due to successive expulsions and limitations on the activities of Jews, notably in the 14th century, there were in fact relatively few Jews in Paris at all between the 15th century and 18th century, when Jews began trickling back. Still, it’s unlikely that there were any Jews in the Marais when, in 1791, during the Revolution, France became the first European country to grand Jews full rights of citizenship. By the early 1800s Jewish presence in the Marais was well established. Jewish arrivals in the quarter, and throughout Paris, took on greater amplitude in the second half of the 19th century, with large movement of Jews from Alsace and Lorraine, where more than half of the Jews of France had lived. Others arrived from Eastern Europe (Romania, Austria-Hungary, Russia), particularly between 1881 and 1914, in the same pogrom-fleeing waves that reached American shores, and Jews continued to arrive in the Paris region into the 1930s.

The Marais thus became home to a grouping of diverse Jewish communities that included Alsatian, Russian, Polish and other Ashkenazic traditions, along with Portuguese and Spanish Sephardic traditions, then in the minority here. In the initial decades of the 20th century one could therefore easily believe that the center of the Marais, comprising large swaths of the 3rd and 4th arrondissements, was Paris’s “Jewish quarter,” though there were in fact mostly non-Jews living throughout this working-class area, much of it very run down.

During the German Occupation of 1940 to 1944 the French police certainly knew how to distinguish a Jewish address from a non-Jewish address; they had identity files, now visible at by the Shoah Memorial, indicating with a large J (for juif) which were Jews. The massive round-up of Jews throughout the Paris region in July 1942, followed by mass deportations to the death camps, removed the “Jewish” from any sense that this was “a Jewish quarter.”

After the war some of those who had managed to flee in time and some of the few who survived the camps returned to the Marais, where, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, they were joined by Sephardic Jews arriving from North Africa as Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco gained independence from France. Though the Jewish presence in the Marais was dramatically reduced compared with the pre-war years (most Jews arriving from North Africa settled in other quarters or in the suburbs), rue des Rosiers and surroundings still visibly formed a Jewish neighborhood.

And now? Are travelers correct in thinking when coming to rue des Rosiers today that they are actually visiting “the Jewish quarter”? Is the presence of Semitic fast food and a few Judaica shops a reflection of a vibrant local community or of successful ethnic marketing or of a combination of the two?

Let’s take a look at what’s here.

Clearly there are Parisian Jews around—clearly, that is, if you walk by one of the active synagogues and religious schools just off rue des Rosiers or look into a kosher butcher shop or one of the less tourist-directed bakeries or visit on a Jewish holiday. A Jewish vocational school still operates at 4 bis rue des Rosiers. On Sundays cliques of Jewish adolescents from throughout Paris gather on the street, though they can be lost in crowd of other visitors, for every Sunday is a non-religious holiday in the Marais and the occasion for all comers to celebrate the pleasures of a stroll in the city.

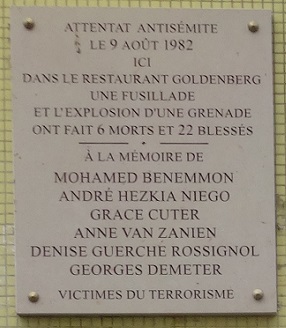

Otherwise one is more likely to catch a glimpse not of neighborhood life today but of the neighborhood that is no longer here: The façade of the old baths (closed in 1989); a plaque indicating that an attack was carried out against Jewish targets by a Palestinian terror cell on August 9, 1982 at the restaurant Jo Goldenberg , killing 6 and wounding 22 (the space is now occupied by a clothing shop); a sign in the middle of the street stating that this was the Pletzl or little square, the crossroads of the old urban Jewish village (in 1900), and signs here and on neighboring streets (rue des Ecouffes, rue des Hospitalières-Saint-Gervais) telling of deportations to death camps.

Otherwise one is more likely to catch a glimpse not of neighborhood life today but of the neighborhood that is no longer here: The façade of the old baths (closed in 1989); a plaque indicating that an attack was carried out against Jewish targets by a Palestinian terror cell on August 9, 1982 at the restaurant Jo Goldenberg , killing 6 and wounding 22 (the space is now occupied by a clothing shop); a sign in the middle of the street stating that this was the Pletzl or little square, the crossroads of the old urban Jewish village (in 1900), and signs here and on neighboring streets (rue des Ecouffes, rue des Hospitalières-Saint-Gervais) telling of deportations to death camps.

Synagogues of the Marais

Attesting to the centuries-old presence of Jews in the Marais, specifically the former parish of Saint Gervais, rue Ferdinand-Duval came to be called rue des Juifs (Street of the Jews) in the late Middle Ages. It was briefly a closed street, though not a ghetto per se since Jews also lived elsewhere in the city. An unsuspecting visitor is unlikely to walk up that little street today thinking that it might ever have been “a Jewish street,” until arriving at its northern end, where it spills into rue des Rosiers. You’ll find more by going one parallel street over in either direction, to rue Pavée or to rue des Ecouffes, where the neighborhood’s Jewish religiosity is more readily visible.

For security reasons, you’ll have to settle for an outer view of the Art Nouveau synagogue at 10 rue Pavée and the religious school across the street. The Pavée Synagogue (the synagogues in Paris are generally referred to by the street on which they’re located) was built in 1913 for the Union of Communities (Agoudas Hakehilos), largely comprised of Orthodox Jews of Russian origin. This high, narrow synagogue was designed by Hector Guimard, the architect famous for designing the entrances to the first Paris metro stations. The Pavée Synagogue, the only religious building to his credit, is less exuberantly Art Nouveau than the metro work, but the rising curves are undeniably his. It was dynamited on the eve of Yom Kippur 1941 by French Nazi sympathizers at the same time as several other synagogues in Paris. Guimard wasn’t Jewish but was married to a Jew—an American at that. Already in 1938 Guimard and his wife had fled Paris at the specter of war and moved to New York City, where he died in 1942. The Pavee Synagogue was restored after the war and is now listed as a Historical Monument. The building also houses aid services for the Orthodox community.

With a kind word and perhaps a small donation, visitors may be able to enter one of the smaller synagogues just off rue des Rosiers on rue des Ecouffes.

The largest synagogue in the Marais is at the district’s eastern edge, on rue des Tournelles, between Place de la Bastille and Place des Vosges. The Tournelles Synagogue, also listed as a Historical Monument, isn’t open for impromptu visits. Those interested in visiting this beautiful structure, built 1867-1876 with Gustave Eiffel’s company involved in the creation of its metallic skeleton, can contact the synagogue in advance to request permission (Synagogue de la rue des Tournelles, 21 bis rue des Tournelles, 75004 Paris). The Tournelles Synagogue backs up to the Vosges Synagogue whose entrance is at 14 place des Vosges. During the Jewish harvest-time holiday of Sukkot passersby will see a hut or sukkah installed on the balcony above the arcade on the square. There’s another handsome synagogue, built in the 1850s, in the northern part of the Marais, at 5 Notre-Dame-de-Nazareth. Taken together, these synagogues attest to the diverse community of Jews had spread throughout the Marais by the end of the 19th century, a century that saw the number of Jews in Paris increase six- or seven-fold. Many more would arrive in the following decades

Neither Rue des Rosiers nor any other area of the Marais was a closed ghetto, though portions might be considered a ghetto in the sense of being extremely run down. Jews were clearly a sizable presence in the Marais by the end of the 19th century, their numbers continuing to climb, however Jews lived throughout Paris in varying density. Rue de la Roquette (past the Bastille just east of the Marais) and Belleville were also had noticeably dense Jewish populations. While some who had distinguished themselves on the social ladder remained in the Marais, others preferred to live in the city’s upscale quarters, such as near the boulevards and quarters being modernized by Haussmann’s transformations of Paris. (Read about the Rothchild family here and the de Camondo family here.)

Wealth in the Marais

Even when Jews returned to the Marais after the war the strong Jewish presence had existed on the southern side of rue de Rivoli and rue Saint-Antoine was, by the late 1940s, largely absent; the homes of French and foreign Jews and non-Jews had been expropriated for the purposes of rehabilitating an “insalubrious” zone. Little by little the Marais lost its craftsmen and its peddlers as it became home to the middle class and to government projects. Yiddish, so frequently heard and read in the Marais prior to the war, had largely disappeared by the end of the 1950s. Another accent arose, that of Sephardic Jews arriving in numbers from North Africa in the 1950s and 1960s. Sephardic rituals replace Ashkenasic rituals in certain synagogues, notably the synagogue on rue des Tournelles that was split in two to accommodate the distinct ritual interests of the Marais. On rue des Rosiers and nearby streets the neighborhood’s Jewish presence remained clear in the cafés and restaurants, local grocers and shops, with some now preferring couscous and bricks over herring and latkes. But the Marais as a whole was on the way upscale. “The Marais” wasn’t yet a call to stroll and shop, to see and be seen, but by the 1980s public funding was pouring into the area to restore its noble historical buildings—the 17th-century mansions and the town houses on Place des Vosges—and poverty, the hallmark of pre-war Jews in the Marais, no longer had a place here; the working class had been pushed to the edge of the city and into the suburbs. The Picasso Museum opened in one of those mansions in 1985, a turning point in terms of the neighborhoods visibility to visitors to Paris. The decade witnessed an acceleration of a transformation of the district’s local population, in the use of its storefronts and in the way in which the Marais was viewed from outside the 3rd and 4th arrondissements. Visitors from elsewhere in Paris and from abroad began to arrive. Gay bars and businesses opened just west of rue des Rosiers and within a few block of rue des Archives.

With rising real estate prices and an increasing number of visitors through the 1990s, shops began catering to clients from beyond the neighborhood. Rue des Rosiers, the remaining portion of the Marais to stake a claim to being the Pletzl—the ever shifting center of “the Jewish Quarter—, once again began to lose its local Jewish identity, though this time without anyone being murdered. Briefly Paris had the distinction of having side by side a Jewish village by day and a gay village by night. That held for about a decade, but as the Marais gained in desirability for increasingly upscale residents and visitors, any sense of neighborhood anywhere in the district largely evaporated.

Of course, Addidas, Kookai and Fred Perry shops on rue des Rosiers can be Jewish operated, as can the real estate on rue des Rosiers, but only foreign Jewish visitors and native anti-Semites consider this a Jewish quarter anymore. Similarly, only visiting LGBTQ individuals and French homophobes consider the area around rue des Archives a gay quarter. Otherwise, visitors are unlikely to have any idea who actually lives in these areas.

The 2000s saw the arrival of something new on rue des Rosiers and perpendicular streets, a new kind of Diaspora. This time it wasn’t a wave of Jewish immigrants arriving but of Jewish recipes, from New York—deli fare, pastrami sandwiches and the like. Oh, there had been pastrami sold here before, but the new deli restaurants marked the transformation of this small portion of the Marais into a Jewish-theme food court.

Though regrettable for those expecting to be visiting a Jewish enclave and a local community, this is simply part of the evolution of the city, just one of many formerly distinct neighborhoods that have been transformed by market forces in recent decades. The neighborhoods of Paris can still be distinguished by architecture, monuments, museums and history, but they are increasingly homogenous with regards to populations living and visiting there.

Wealth is the historical feature that the central Marais most recalls. After all, nobility and financiers began buying up lots here in the second half of the 16th century, and during the 17th century this became the most fashionable quarter of Paris thanks to the construction of Place des Vosges and of dozens of noble mansions. That was before there was a significant Jewish population here. It was the downfall of French nobility during the Revolution that gave Jews the freedom and elbow room to increase in numbers in the Marais. It was persecution elsewhere, hope for a better life and a need for community that caused the number of Jews in the Marais to swell in the late 19th century. It was also sense of security, hope and community (along with fun) that led to the opening of gay bars and businesses nearby in the late 20th century. The Marais was less desirable for business ventures then. Now, 400 years after the royal inauguration of Places des Vosges, the re-establishment of the Marais as a prized destination and residential area is a sign not such much that it has lost its Jewishness as that it has regained its lettres de noblesse—at least de bourgeoisie.

The Jewish Food Court

French and foreign visitors from beyond the quarter now frequent rue des Rosiers primarily for the shopping and the falafels—falafels, enjoyable as they may be, aren’t a reflection of local community or agriculture or known-how but of what visitors are happy to purchase. Hungry visitors will line up at the falafel window at L’As du Falafel as though the several other similar stands on the street had all failed their latest health test or lost the recipe for frying chickpea balls and slicing cabbage. The devotion to queuing there, particularly on Sunday, is partially due to the perverse lingering effect of an old article in the New York Times, partially due to the hawkers out front (once you’ve paid you’re stuck waiting), partially due to the fact that it’s kosher, whatever the latter may mean to the vast majority of those in line. As to quality, if you’re a serious student of fried chickpea balls and sliced cabbage in Paris then you should try them all. But if you simply want to eat a falafel pita sandwich any stand will suffice.

The street’s other hotspot is Chez Marianne, which takes its French republicanism seriously enough to present itself as French first, Jewish second. Chez Marianne, at the corner of rue des Rosiers and rue de l’Hospitalières Saint-Gervais, serves all kinds of delicious Mediterranean mush (eggplant, hummus, tzatziki, tarama, tapenade, etc.) as well as falafel, so there’s something for everyone. It isn’t kosher and so is open daily noon to 11pm. There are other choices in the area for a decent pastrami sandwich and well-oiled latkes, as well as some fine Ashkenazic bakeries. And there’s one remaining café that on weekdays still maintains a neighborhood feel, Les Rosiers, at #2 on the rue. Meanwhile, while fast foodies are now able to enjoy pastrami sandwiches and other New York imports in other quarters of Paris as well (e.g. meaty Freddies Deli in the 11th or vegan MOB in the 13th), while falafels are more common than crepes on some streets.

But I digress. The purpose of this article is not to recommend specific eateries in the Jewish food court or to speak of recent influences to the Paris fast food scene but rather to encourage those interested in Jewish history to look beyond the 20 years of Marais history represented by the Mediterrean-meets-NY-deli food offerings on rue des Rosiers. Enjoy them, enjoy that lingering scent and that occasional glimpse of the Pletzl and an old Jewish quarter—and why not enjoy them insightfully after working up an appetite at more instructive sights? The Deportation Memorial, the Shoah Memorial and the Holocaust Center would be fine places to start. You can begin by reading about them in this next article.

© 2014, Gary Lee Kraut

Gary, this is an excellent article. I have seen the street evolve from 1970, when it was still very Jewish, through the gay period, the trendy, expensive shops and now the trendy chain stores.

Thanks, Ellen. I’ve personally known the area only since the late 1980s when the evolution in tourism and real estate prices was already underway. Knowing the area in the 1970s must have been particularly fascinating. Gary