The Nissim de Camondo Museum overlooking Parc Monceau in Paris presents an extraordinary collection of 18th-century decorative arts, reveals the technology and services of an ultra-modern early-20th-century home, and tells of the life and times of the de Camondo family as bankers, philanthropists, collectors and Jews.

* * *

Between 1870 and 1900, a period of great influx of Jews into France, you’d be unlikely to find a wealthy Jewish resident of Paris going into the Marais for kugel or gefilte fish, let alone a falafel. Leave that to the tourists and the working class schnooks, they’d say. Well, maybe not. Maybe they’d send a servant or two to Rue des Rosiers for some kishke and kreplach or stay for a meal when in the neighborhood for some philanthropic mitvah.

Otherwise, prosperous Jews in Paris in the latter decades of the 19th century likely felt more at home among the bankers, industrialists and aristocrats of the 8th or 9th arrondissements than in the Pletzl, the Little Place, as the heart of the then-significant Jewish Quarter around Rue des Rosiers was known. In any case, wealthy Sephardim, such as the de Camondo family, a Jewish banking family that had made its fortune in the Ottoman Empire and Italy, would have been more familiar with Turkish spanakopita and kaskarikas and yufka than with the Ashkenazi fare found in the Marais, where the vast majority of Jews were then Ahkenazim. Anyway, by the time the de Camondos established residence in Napoleon III’s France in 1869, they were probably well accustomed to the foodstuff of aristocracy.

The Camondo family’s rise in wealth originated through commerce at the end of the 18th century. By the early 19th century the fortune was sizable enough for Isaac Camondo, based in Istanbul, to open a bank in his own name. Isaac died without children and so his brother Abraham Salomon Camondo (1781-1873) inherited the bank and greatly developed. Having aided Italian unification through loans to the newly formed kingdom, Abraham and his grandsons (Abraham’s son died in 1866) were ennobled by Italy’s King Victor Emmanuel II. The parallel with the (de) Rothschilds led the (de) Camondos to be known as “the Rothschilds of the east.” (See this article about the Rothschilds in Paris.)

The Camondo family’s French story begins in 1869 when the elderly Abraham Salomon Camondo followed his two grandsons Abraham (1829-1889) and Nissim (1830-1889) to Paris to further grew their successful family.

Abraham and Nissim elected to live in what was then becoming one of the most exclusive quarters in the capital, the area around Parc Monceau. Through the 1860s and into the 1870s, members of the imperial aristocracy and of the haute bourgeoisie built stately mansions surrounding the park’s genteel greenery and theatrical décor. Here one could stroll by a colonnade of Corinthian columns in partial ruin, watch duck in the oval pond of a naumachia (the basin Romans used for mock naval battles), walk over a Chinese bridge and visit an Italian grotto and an Egyptian pyramid. The sight of well-dressed (faux) explorers visiting (faux) ancient ruins on an afternoon in Parc Monceau might have been reminiscent of paintings by 18th-century French painters Watteau, Fragonard, Lancret or Bouchet found in the Louvre—or on the walls of neighborhood residence since living with great wealth now required a backdrop of great art and perhaps some antique furnishings.

Soon after they arrived in Paris, brothers Abraham and Nissim de Camondo built mansions side by side overlooking the park. Several streets away, Edouard André, heir to a Protestant banking family, built an even more ostentatious home on the new and expansive Boulevard Haussmann. When, in 1881, André married Nélie Jacquemart, they formed a couple of the most devoted art collectors in Paris. Their home and collection are open to the public as the Jacquemart-André Museum, which gets the lion’s share of museum attention in the quarter, leaving relatively few visitors to the exceptional home and collection of Moïse de Camondo.

The collectors in the de Camondo family weren’t brothers Abraham and Nissim, who arrived in Paris as business-minded adults, but their respective sons, Isaac (1851-1911) and Moïse (1860-1935). The cousins continued to live side by side after their fathers died, both in 1889.

The Republic of France was the center of the art world between 1870 and WWI, and while Isaac had a taste for modern art, Moïse (Moses) was devoted to the styles of the pre-Revolutionary Kingdom of France. Having arrived in France as a child, Moïse developed a taste in decorative arts that was more French than the French. He considered the beauty of decorative art of the 18th century, particularly the period from 1750 to 1789 (the second half of Louis XV’s reign and Louis XVI’s full reign) as “one of the glories of France.”

Moïse de Camondo, like his cousin next door, grew up in a Napoleon III-style mansion bought by his father in 1870. After the death of his mother in 1910 he had the home demolished in order to build his dream home. Modeled after the Petit Trianon, that little jewel of a palace at Versailles that Marie-Antoinette used as her getaway house, Moïse’s new home combined the luxury of a modern mansion of the 1910s with a space that could ideally present his 18th-century decorative treasures. (The former home of his uncle Abraham and cousin Isaac, which would have had much in common with the home Moïse had demolished, can still be seen next door.)

The brothers would eventually bequeath their extensive art and decorative collections to French cultural institutions. Isaac, who never married, left his collection of Impressionist and post-Impressionist paintings to the Louvre (many of them are now in the Orsay), while Moïse bequeathed his home and collection of 18th-century decorative arts to the Union Central des Arts Decoratifs. The UCAD, an institution created in 1882, is now called Les Arts Decoratifs, and oversees the Museum of Decorative Arts and affiliated museums, including the Nissim de Camondo Museum, where Moïse’s home and collection are still largely presented as he wished.

Whether or not you’re greatly interested in 18th-century decorative arts, the museum is remarkable in its combination of three different points of interest: an extraordinary decorative arts collection, the technology and services of an ultra-modern home of the early 20th century, and the life and times of the de Camondo family as bankers, philanthropists, collectors and Jews. Use of the audio-guides (free with the entrance ticket) or a human guide is highly recommended.

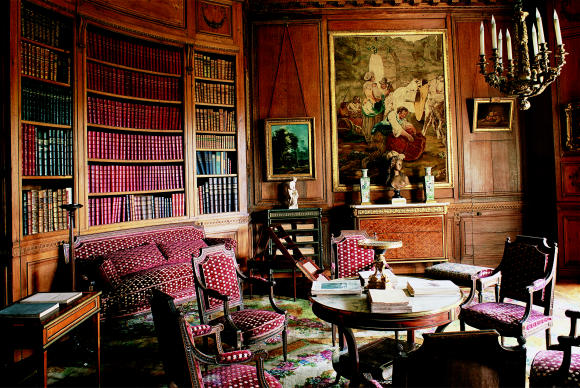

Rooms specially designed to receive Moïse de Camondo’s growing collection are fitted with antique wood paneling and present marquetry, inlaid tables and other furnishings by great names of French cabinetmaking in the latter decades of the 18th century, such as Oeben, Riesener and Jacob, along with paintings, bronze clocks, vases and chandeliers. Methodical in his purchases and with a sense of symmetry in his home, he often purchased items in pairs. The pieces often have a known history relative to high aristocracy or royalty, such as Marie-Antoinette’s chiffonier, a table for her needlepoint work. A room off the dining room was built to showcase Moïse’s porcelain collection, including two Sèvres dinner services (“Service Buffon”), each piece of which is illustrated by a different bird.

Advised by curators at the Louvre and the Union Central des Arts Décoratifs and in contact with major antique dealers, Moïse continued to enrich his collection until the end of his life. He sold pieces to buy better pieces.

While wishing to present the art de vivre of the ancient regime, Moïse de Camondo had also instructed the architect René Sergent to provide all of the high-luxury comforts of his own time, complete with an ultra-modern kitchen, heating, bathrooms and car park.

In an alliance of two powerful banking families, Moïse married Irène Cahen d’Anvers in 1891. Irène had been painted by Renoir as a child, her curly long brown hair falling down her back and wrapped around her shoulder like a fur cape. They were married at the Grande Synagogue de Paris on Rue de la Victoire. Five years and two children later she fell in love with an Italian count who was a racehorse trainer, the era’s equivalent of running off with the pool boy. In the divorce, Moïse was granted custody of the children.

Their son Nissim (named for Moïse’s father) was the intended heir to the home and his collection, as well as of the bank, but he predeceased has father, dying in air combat during WWI in 1917. Moïse then closed the bank and eventually bequeathed the mansion and its furnishings to the Union Central des Arts Décoratifs in Nissim’s memory.

Their daughter Béatrice showed no interest in her father’s passion for 18th-century decorative arts. She nevertheless inherited a sizable fortune. Horses were her passion, and in any case she had a family and home of her own. During the German occupation of WWII, she felt protected from expanding anti-Jewish policies by her wealth, assimilation and position in French society. By then, her late father’s Paris home and collection had become a museum. If she had inherited them the collection would undoubtedly have been dispersed since her own possessions were eventually seized when she, her husband Léon Reinach, and their children Fanny (born in 1920) and Bertrand (born in 1923) were arrested in 1942 for being Jewish and deported (Léon, Fanny and Bertrand in Nov. 1943, Béatrice in 1944) to the death camp at Auschwitz. They did not return.

This is one of the most beautiful of lesser-known museums of Paris enlivened by a fascinating family history, ideally followed up by peaceable stroll through Parc Monceau.

© 2013, Gary Lee Kraut

Musée Nisim de Camondo, 63 rue de Monceau, 8th arr. Metro Villiers or Monceau. Tel 01 53 89 06 40 or 01 53 89 06 50. Open Wed.-Sun. 10am-5:30pm. Entrance: 7€50, includes audio-guide. Joint tickets including entrance to the Museums of Decorative Arts, Fashion and Textile and Advertising, all on Rue de Rivoli, are available for 12€.