It’s a small step from novelist Gil Pender’s encounter with Ernest Hemingway in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris to writer Elizabeth Esris’s encounter with Josette in real life’s early morning in Paris. In fact, just around the corner, as Elizabeth tells in this exquisite travel story.

* * *

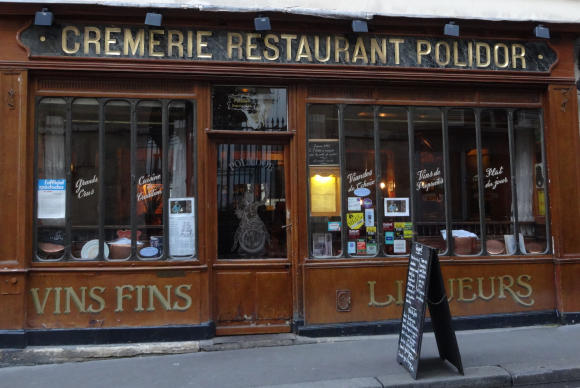

Aspiring 21st century novelist Gil Pender walks away perplexed but elated after a conversation with Ernest Hemingway at Restaurant Polidor in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. Hemingway promises to show his novel to Gertrude Stein, and Pender is off to pick up the draft when he remembers that he never established a place to meet Hemingway on his next magical midnight excursion to the 1920s. Turning back to retrace his steps in the darkness of early morning, Le Polidor has vanished and Gil finds a sleepy green glow illuminating dormant machines in a laundromat where moments before Hemingway had been drinking wine and imparting truncated macho aphorisms.

At that moment I was still laughing at the caricature of Hemingway. He was so like the cartoonish image I had envisioned decades earlier within the penumbra of mid-20th century America when many English majors suffered what Hemingway biographer A.E. Hotchner described as “an affliction common to our generation: Hemingway Awe.” But I laughed more when I recognized the laundromat as the one that is directly across the street from the Polidor on rue Monsieur le Prince. My laundry had tumbled in those machines a number of times. I suspect that, like me, other aging English majors continue to be charmed by the “lost generation” that Woody Allen eulogizes and laughs at in Midnight in Paris. And like me, they may still carry a notebook wherever they go—even to a laundromat.

The last time I did my laundry on rue Monsieur Le Prince it was early morning. My husband was off to a business meeting in Lille and I was alone on a rainy and chilly summer day in Paris. I looked forward to just walking and finding a comfortable spot to read and write. After depositing my laundry in a washing machine, I headed toward the Luxembourg Gardens. I was attired very casually since I couldn’t dress for the day until my laundry was done. I felt comfortably anonymous, and when I stepped under the awning of Le Rostand, I chose to sit outdoors even though all of the other customers were inside.

I took a table next to the door, furthest from the street and the rain. The waiter came and then went to get my café and I opened my notebook. I glanced toward the gardens just opposite and felt a wonderful sense of satisfaction.

I looked up when the waiter returned and saw that another woman was electing to sit outdoors, but in contrast to my well-worn zip-front and Velcro nylon rain jacket and Teva sandals, this woman wore an elegantly tailored fitted raincoat, an indigo silk scarf shimmering around her neck, and flesh-colored pumps. She carried an umbrella and a small buttery handbag.

When the waiter noticed her he almost clicked his heels. She greeted him by name and looked toward my table: I knew instantly that it was hers. When she took the table next to mine the bulge of my backpack in which I had carried the laundry seemed to groan with shame. As she sat, she put her purse on the table; our eyes met and she smiled. She knew I felt ill at ease. I murmured “Bonjour, Madame.”

The waiter took her order and then she rose to go indoors. She was about my age and I knew where she was headed. She was about to take her pocketbook with her when she changed her mind. No matter how nice the café, the toilettes is a limited space at best. She intimated with gesture and a knowing smile that I should keep an eye on it, and with some stumbling French I nodded in accord. How many times had these same silent messages been passed between me and female friends at home? I was amazed by her delicate sense of civility and at her graciousness in acceding to a sisterhood of trust. The rain came down harder as I waited for her return and I felt a compliment that almost moved me to tears.

The watched purse engendered conversation when she returned. She thanked me with a warm, sincere smile. I introduced myself as Elizabeth and she said she was Josette. There was no need to say I was an American. She told me in French that although she knew some English, she did not speak it because her mastery of it was flawed. At that moment I was grateful that this was the last leg of a three-week trip that had taken us through Provence and into the Dordogne; as always, language improves with immersion. I was happy to struggle with French and she was gracious. The waiter watched as we chatted.

Josette asked what brought me to France and I told her about our vacation in the south and the few days in Paris where my husband had business. She asked where I was from in the U.S. and I told her I lived outside of Philadelphia, not too far from New York City. She said she had lived briefly in New York and that was where she had practiced the English she had learned in school but never quite mastered. She said that she felt inadequate during that time and that it ruined any desire to stumble with English again. I encouraged her by citing my own joyful struggles with French, but I understood that this was a matter of principal and pride that was deeply woven into her being. In response to my question as to what took her to New York to live, she told me her husband worked for the government. She did not tell me his position and I refrained from asking, but she said that because of it, they had lived around the world for many years. When she spoke of “his work” I was acutely aware that we were close to the French Senate as well as the University of Paris. I also recalled how the waiter deferred to her.

For the next forty minutes I extracted from myself all the French I knew, and because of both her patience and steadfast avoidance of English, as we spoke of children and schools and travel, I learned a few new words and validated my long-held belief that great conversation is always possible when strangers look to each other with respect.

The richest part of our conversation was about Paris. When I told her how I had come to envision and love France and Paris as a young woman reading de Maupassant and Hugo and Flaubert and Fitzgerald and Hemingway, she nodded with understanding and said that Madame Bovary was a particular favorite of hers. It was one of mine, as well. She asked if I had been to the Pantheon to visit the tombs of Hugo and Zola. She said that to her Paris was very beautiful in a physical sense but that more importantly it was a reminder that mankind is capable of beauté et dignité.

When we first began talking I was dreading the moment when my laundry would be done and I would have to excuse myself from the conversation; I was certain that this was a woman who rarely washed her own clothes. My pride, bedraped by worn travel clothes and a backpack, was inflamed. In my mind I had conjured excuses: “Excusez- moi, mais j’ai un rendezvous” or perhaps “Excusez-moi, je dois quitter de rencontrer a un ami.” As the hands on my watch approached the time, however, I felt that I was at the end of a chance meeting with an elegant, perhaps important woman who had savored our forty-minute conversation on a rainy morning in Paris as much as I had. I knew that she appreciated my enthusiastic, often bumbling French and she complimented my accent a couple of times. More than that, however, we had spoken as women speak everywhere; we unfolded a bit of the panorama of our lives before each other, and in between words there were smiles, nods, and eyes that met in understanding—just as they had met when I realized I was sitting at her usual table and when she asked me to watch her lovely handbag.

When I knew I had to leave I said, “Excusez-moi. Je dois prendre mes vêtements à la laverie de la rue Monsieur Le Prince.” We smiled, shook hands warmly, uttered each other’s name as we said au revoir, and I walked back to the laundromat in the gentle rain.

While my clothes were tossing in the dryer I took out my notebook and jotted down what I remembered about my early morning café at Le Rostand. I wanted to save the moment because I knew that if, like Woody Allen’s Gil, I retraced my steps, it would be gone.

© 2013, Elizabeth Esris

Other great travel stories and poetry by Elizabeth Esris can be found here.

a scene sweetly and richly rendered…