As France celebrates the 400th anniversary of the birth of André Le Nôtre, the father of French gardens, France Revisited explores some of this 17th-century landscape gardener’s most famous gardens and parks. Here, in text and images, American photographer Elise Prudhomme, a longtime Paris resident whose work has been exhibited in the Tuileries Garden and will soon appear in an exhibition in Versailles, guides us along the garden paths of Versailles.

* * *

By Elise Prudhomme

André Le Nôtre designed the Garden of Versailles to display, reflect and serve as the backdrop for the pomp and glory and power of the reign of Louis XIV. As such the garden functioned as a direct extension of the palace itself.

Piqued by Nicolas Fouquet’s audacious success with the Château of Vaux-le-Vicomte which he visited in 1661, Louis XIV enlisted the three men who had contributed to that success—the architect Louis Le Vau, the painter-decorator Charles Le Brun and the landscape gardener André Le Nôtre—to create the palace of all palaces: Versailles.

Over more than 50 years of adult reign, the king would devote much of his time and energy, when France was not at war, to enlarging and embellishing the 800 hectares (1977 acres) of land called the Domain of Versailles which now contains 200,000 trees, 50 fountains and 620 water jets fed by 35 km (21.7 miles) of water pipeline. In a monumental example of man’s attempt to balance order and disorder, culture and nature, spontaneity and reflection, Le Nôtre served the king by creating architecture from nature.

Through his self-incarnation as the Sun King, Louis XIV used metaphor and symbolism as constant echoes and demonstrations of his power. From the king’s ceremonial dressing and rise in the morning (le lever du Roi) to his ceremonial undressing and putting to bed at night (le coucher du Roi), by way of a well-regulated day that included a walk in the garden under the watchful eye of the Court, Louis XIV exposed his lives to the public eye with the aim of concentrating and asserting their power. Integral part of this goal, the Garden of Versailles served the strategic purpose of promoting the king’s power while amusing and containing the masses of Court subjects, twin arms in preventing them from plotting against him.

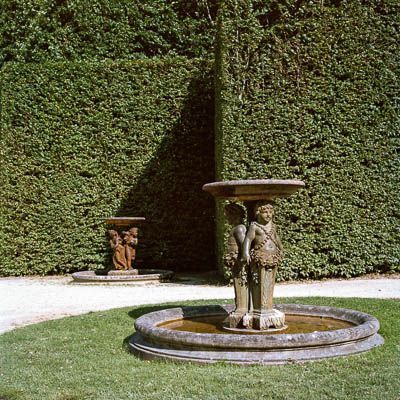

The garden was an immediate reflection of his public image as the Sun King. An important quantity of statuary representing classical themes was ordered in 1674 by Louis XIV to embellish the parterres, and in the same year the king ordered the addition to the Grand Canal called Little Venice where gondolas and decorative boats were docked to serve the pleasures of the Court. Louis XIV’s strongest ally, Apollo (the Greek Sun-god or God of Light), is represented in fountains and grottos and statuary throughout the garden to allude to the king’s omnipresence.

The mastermind behind this colossal project was André Le Nôtre. The king himself poured over the plans. Careful and strategic planning was required to create a garden that was at once opulent, in phase with the palace, able to reveal and dissimulate through nature so that discovery of the garden became an adventure and a distraction in itself, all the while speaking of the power and glory of Louis XIV.

The foundation of André Le Nôtre’s creation was shear manpower; millions of men, regiments even, were involved in transforming the landscape and diverting water here. Chariots and wheelbarrows containing countless tons of earth were required to transform the prairies and swamp land which originally constituted the Domain of Versailles. Trees were brought to Versailles from all over France to stabilize and maintain this earthly base, transforming flatlands into hilled woodland. Andre Le Nôtre worked with subtlety and mathematical know-how, tried and tested at the Tuileries Gardens and Vaux-le-Vicomte, to create illusions of perspective which evolve as the garden unfolds.

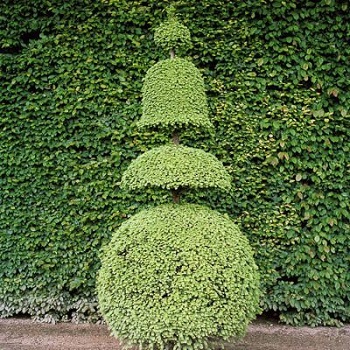

André Le Nôtre’s genius is particularly evident in the walls of the Sun King’s “outdoor palace.” Masses of hedges form bosquets, behind which follies and fountains reveal themselves like little theaters or tableaux vivants. Walking through the gardens, one is struck by the density and size of these thickets and the quantity of trellis work that prevents the untamed forest areas from invading the paths. While providing shade, these geometrically trimmed vegetal walls protect from wind and give shelter to birds and small wildlife. It is interesting to notice today that the areas of the garden that are in the process of being replanted are initially delimited by trellis work, as if the first step in the garden’s construction.

André Le Nôtre did not content himself with the construction of just one wall, however; there are walls within walls. The bosquets are often doubled with a second wall of vegetation, trimmed and adorned with statuary which offers heightened visual complexity and a shady path. The final flourish is a third row of topiary statues, notably along the east-west axis extending from the palace to the Grand Canal and the north-south axis leading to Neptune’s Basin. Nature in this case, serves a decorative rather than functional purpose, heralded by white marble or dark stone statuary providing contrast in texture and color to the pervasive green of the garden.

This is the orderly representation of the Garden of Versailles, where nature is trimmed (they cut the topiary statues using life-size cardboard models for accuracy), trained, maintained. This is also a visually unstructured aspect of André Le Nôtre’s garden architecture which is demonstrated in the King’s Garden: here an aboretum coexists in harmony and color with low topiary hedges and grassy lawns. The trees act like a bosquet, preventing the viewer from seeing out beyond his immediate surroundings, while providing shelter from wind.

The Park of Versailles begins past the Apollo Fountain and beyond the wrought iron gates that delimit the Garden of Versailles. If the Garden of Versailles is Louis XIV’s outdoor palace, the park—which includes forests, fields and the gardens of the Trianon Palaces—can be seen as the garden of the Garden, in that it is just as carefully maintained and planned in its “wooded” form as the former is in its “constructed” form.

Walking past the garden gates one leaves beyond the imposing formality of the Garden of Versailles to visit the Grand and Petit Trianons and their respective gardens and beyond the Petit Trianon to the Queen’s Hamlet, a quaint working farm as desired by Marie-Antoinette. These gardens are exceptionally charming because they are smaller in size and scope as well as being less formal and more romantic, making them a treat for any photographer willing to venture beyond the crowds.

While André Le Nôtre successfully built Louis XIV’s garden to reflect the king’s power and to capture the attention of the masses, I don’t believe that he could have imagined in his wildest dreams that this glorious place would attract some many visitors for many years to come. Yet the garden still manages to conquer in splendor. Now, if only they would replace the golf carts and tourist “trains” with Apollo’s chariots and horses.

Text and images © Elise Prudhomme.

A Philadelphia-born photographer living in Paris since 1990, Elise Prudhomme developed a passion for photography during university years at Smith College. In addition to her own photography, she directs Studio Galerie B&B, an art gallery, photo studio, darkroom facility and digital imaging center in Paris, 6 bis rue des Récollets, near Canal Saint-Martin in the 10th arrondissement. More images can been seen at www.eliseprudhomme.com.

Also see Elise’s text and images concerning the Tuileries Garden.