In this cross-Atlantic travel article Elizabeth Esris examines the beauty and the history of the village of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert in southwest France and then returns home to discover some of its missing elements at The Cloisters in New York.

* * *

The largest plane tree in France sits like a beloved grandfather in the square in Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, an ancient village in the Hérault Valley, 27 miles west of Montpellier. Children race around its massive trunk and stop to drink from the multiple spouts of the nearby fountain topped by Liberty. Adults sit in its shade to chat. It’s a beautiful, comfortable spot whose history runs deep, but it was not on our itinerary as we originally skirted this part of the valley on our way from Provence to Toulouse.

A chance encounter with a shop keeper in Pézenas, a wine town among the vineyards between Montpellier and Béziers, however, made us change directions and head north into the Hérault Gorges. The shopkeeper’s excitement about the beauty and history of the village convinced me and my husband that a detour would reward us with a memorable stay. She was right, and at the time we did not realize that we would come face to face with sublime architecture, some of which could be found just a short drive from our home in Pennsylvania.

Approached from the south along the Herault River, Saint-Guilhem-le-Desert is heralded by a striking series of bridges, including the medieval Pont du Diable, arched high above a steep gorge lined with grey-white rocks that look as if they had been drizzled down the cliff.

The village itself is surrounded by chalky limestone mountains stippled with green shrubs. Embedded in the hills are the remains of a Visigoth fortress and a dusty old mule path, portions of which have been traveled for centuries by pilgrims following the sign of the shell that marks routes of the Way of Saint James leading to the cathedral in Santiago de Compostella in Spain where the remains of St. James the Greater are said to be buried. Today this path also affords walkers day hikes that begin at the edge of the village on the rue du Bout-du-Monde, the street of the end of the world.

The graceful, rounded apse of the Abbey of Gellone dominates the pale buildings with tiled roofs that emerged as we drove past a gentle flow of the Verdus, a stream that keeps the area verdant as it runs toward the Herault River. We parked the car and walked a narrow street that led to the main square. Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert can be filled with tourists, but as with any well-known site, arriving off-season allows for less hindered signs of the past and of local life.

Those signs were already clear from the hotel room we found, from which we could hear the bells of the abbey, the greetings of residents on the pavement and watch an old dog make his way from the direction of the square toward the welcome of a water bowl.

As we meandered through the cobbled streets of the village we spotted scallop shells embedded in fountains and near doorways as signs of welcome for pilgrims traveling the Way of Saint James. We wondered if these doors opened as readily today to pilgrims as they had in past centuries.

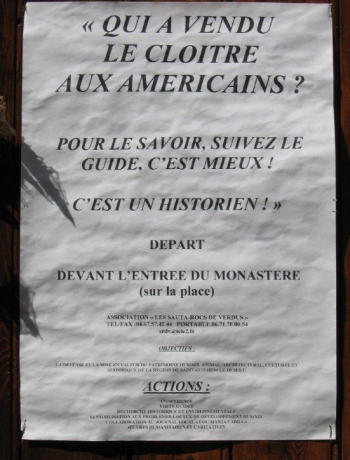

We were charmed by the personalized doors and windows that reflect the artists who reside in the village; we were also struck by a few handmade signs protesting the possession of the original cloister from the Monastery of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. One poster advertised a meeting where a speaker would ask the question “Qui a Vendu Le Cloitre aux Americains?” Who sold the cloister to the Americans?

The Cloisters, in northern Manhattan, is the branch of The Metropolitan Museum of Art dedicated to the art and architecture of Medieval Europe. It sits majestically atop a hill in a lush 66-acre park with wonderful views of the Hudson River. The impressive monastery-like building is, according to the museum’s website, “not a copy of any specific medieval structure but is rather an ensemble informed by a selection of historical precedents, with a deliberate combination of ecclesiastical and secular spaces arranged in chronological order.” The Cloisters developed out of an impressive collection of cloister sections and other medieval art accumulated by American sculptor George Grey Barnard early in the 20th century. That collection was later acquired and curated at the Fort Tryon site through the donation of land and funding by John D. Rockefeller. Among the highlights of its ecclesiastical spaces is a cloister, one of five, created with 140 fragments from the cloister of the Monastery of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert that, according to the museum, Barnard had discovered being used as “grape arbor supports and ornaments in the garden of a justice of the peace in nearby Aniane.”

The monastery in Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert dates to the 9th century when it was founded by Guilhem, Count of Toulouse and grandson of the Duke of Aquitaine. Guilhem was a cousin of Charlemagne and noted in his time as one of the emperor’s most valorous knights for his battles against the Saracens of Spain. For centuries that followed Troubadours sang about his bravery. Charlemagne presented him with a piece of the Holy Cross (it was an age of relics) that he brought with him when he came to establish a home and a monastery in 804 in the remote region that would eventually bear his name, Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert. (“Le Désert” refers not the geography but to the absence of people in the area at the time.) The relic helped make the Abbey of Gellone an important stopping point for pilgrims on the road to Compostella, and it remains there to this day. Despite his life as a warrior, Guilhem was deeply religious and spent his final years at the monastery as a monk from 806 until his death in 812.

Thanks to the traffic of pilgrims, the monastery prospered and most of the Abbey of Gellone visited today dates from the 11th century when it was rebuilt in the Romanesque style. Like many monasteries in France it eventually suffered from the vicissitudes of faith and politics. It was pillaged during the Wars of Religion and vandalized during the French Revolution, losing both furnishings and architectural elements. Each historical trauma, whether natural (e.g. floods) or man-made, led to more decay, and by the 19th century parts of the abbey were dispersed throughout the region, including sections of the cloister later purchased by Barnard.

The interior of the abbey conveys an intimacy and warmth due in part to the variegated rustic tones of the stone. The vault of the soaring apse is punctuated by three high windows that represent the Trinity, and an ornate marble and glass altar presents a stunning contrast with the simplicity of architectural line. Near the altar rests what are said to be the remains of Saint Guilhem and the relic of the Holy Cross given to him by Charlemagne. There are lovely spaces within the abbey, one of which houses an 18th-century organ. The abbey has an atmosphere that suggests mystery and evokes contemplation. It is also a perfect venue for intimate musical performances such as the string and flute ensemble we attended during our visit. The cloister that was rebuilt in the second half of the 20th century, which includes a few original columns, also affords a quiet retreat.

The village of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert appears to flow from the monastery. The narrow streets that begin at the portal of the abbey on the square seem a natural path to the beauty of the tight houses and the chalky tops of the mountains that appear beyond their roofline. An approach to the village offers a lovely view of the rounded apse symmetrically flanked by the round exterior walls of two smaller curved vaults and bordered by a low wall encasing a small garden. The exterior of the monastery, however, does not convey the serenity of the interior. Evidence of the tumultuous past is reflected in the monastery’s outer surfaces in color variation, patched walls, and solid sections that seem almost fortress-like. Still, there is a sense of calm and history as you walk between trees and flowers and enjoy time along a quiet path.

* * *

We drove to The Cloisters Museum in the fall on a radiant day much like the one that welcomed us to Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert. The museum rises from the topmost height of lushly wooded Fort Tryon Park on which it occupies four acres. It conveys medieval perfection through its stone tower, unmarred arches, metal steeple atop a spire such as those found on village churches in the south of France, and the graceful curve of an 11th-century apse from a church in Spain. It may be “an ensemble informed by a selection of historical precedents” but the total effect of The Cloisters is that you have arrived at another time and place. Cobbled paths wind up a hill toward the powerful stone structure, and visitors step into remarkable spaces that belie the 21st century. The statuary, paintings, tapestries and other artifacts humanize the medieval world. Coming so close to medieval art within authentic stone chapels and chambers and gazing into the faces of sublimely painted wooden sculptures makes a connection to ancient life that is transformational.

Four of the cloisters at the museum have outdoor settings with skillfully tended gardens. Everything appears natural and free; the eruption of color and texture suggest a rustic landscape, but the reality is far more calculated. The Cuxa Cloister from a Benedictine Monastery near the Pyrenees in Spain is breathtaking; stone pathways, flowers, trees, and dense foliage frame pink marble columns, a central fountain and low tiled roofs. It is a realization of how we imagine a medieval cloister to have looked and felt.

The reconstructed cloister from the Monastery of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert at The Cloisters is an interior space with a high glass ceiling for natural light and lovely arched windows that overlook the Hudson River behind one side of the cloister. A few potted plants and some large vessels from the period dot the hard pebbled courtyard. The columns are stunning, set in pairs to support the arched stone of the installation. They vary in both the shape of the columns and design of the capitals. Some of the columns are rounded, others hexagonal, still others are ornate with waves from top to bottom, and some are wide and fully sculpted. The capitals are carved with exquisite renderings of acanthus leaves, vines, flowers, honeycombed patterns and both animal and human figures. The passageways behind the columns suggest a sense of contemplation with stone benches for reflection. Care has clearly been taken to respect the extraordinary craftsmanship in the stonework and gracefully echo the serenity of a monastic setting.

I wanted to love this cloister, but I could not. I felt the artifice of museum lighting despite the open ceiling, and I begrudged the closed space that made it more of an exhibit than a setting where imagination might take you back in time. Viewing the columns from multiple perspectives, I tried to place them mentally at the peaceful Monastery of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, among the trees and flowers, the passageways to the abbey, the prayers of monks and the footsteps of approaching pilgrims. I wanted to see them not as individual elements of interest but as an essential part of an idea, a purpose, a commitment to the necessity of contemplation and prayer. Instead, despite the splendor of The Cloisters and my appreciation for how it celebrates the beauty and humanity of medieval life, makes it accessible to so many and preserves it for the future, I found myself wishing I had attended the lecture that answered the question, “Who sold the cloister to the Americans?”

© 2013, Elizabeth Esris

Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, population 265 (2012 figure), is located in the department of Hérault in the region of Languedoc-Roussillon. The village’s official website, which also provides information about the surrounding Hérault Valley, can be found here. Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert is a member of the association Les Plus Beaux Villages de France.

The Cloisters Museum and Gardens, Fort Tyron Park, New York, New York 10040. The website for The Cloisters contains a wealth of information. In exploring the site you will discover photos that show Barnard’s collection as it was originally displayed in New York City. Worth accessing are wonderful videos that detail the history and construction of the museum in Fort Tryon as well as detailed videos that focus specifically on the reconstructed cloisters, including further information about the cloister from Saint-Guilhem-Le-Désert.

Elizabeth Esris is a teacher and writer. Her poetry has appeared in Wild River Review, Bucks County Writer, and Women Writers. She wrote the libretto for Elegy For A Prince with composer Sergia Cervetti which premiered in excerpts at New York City Opera’s VOX Opera Showcase in 2007. She and Cervetti also collaborated on a one-act chamber opera, YUM!, a celebration of wine, food, and friendship. She teaches English and creative writing at Central Bucks High School South (Pennsylvania).

Other work by Elizabeth Esris on France Revisited include this article and poem about the Luberon and this article and poem about the Abbey of Senanque.

The Cloisters is an amazing treasure. I spent a lot of my childhood there and then grew up to incorporate those memories into my novel SWIMMING TOWARD THE OCEAN (Knopf).

It must have been a magical place to explore as a child! I must read your novel.

It is time to return all treasures and artifacts to their countries of origin – where they may be appreciated as they were intended.

Hi Elizabeth, I am bowled over by your writing about Saint-Guilhem and the cloisters museum. I’ve just visited the village and abbey last week, and am trying to write a blog post aobut it. Having read your article makes it all the harder, but in a good way!

Dear Elizabeth, there is so much more to this, as George Grey Barnard probably knew, for he had this vision to also rescue parts ( I think) before WWII. I have been to both places too! Somehow I got into a quest that is amazing. But it is difficult to tell fantasy from truth. Thanks for the article!!