Much has been said and written about the theatrical, heretical and provocative sides of Salvador Dali: his pathological ego, his paranoia, his love of money, his conversion from Marxism to monarchism, his ambiguities with respect to Franco and Hitler, his wild mysticism, etc.

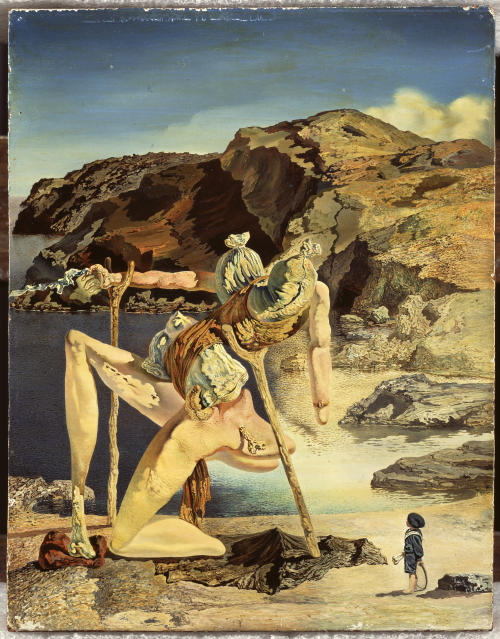

Perhaps too much, for speaking of Dali in those terms has a tendency to mask the fact that he was the last giant of the history of 20th-century art, an equal to Picasso, and that this surrealist who swore by the Renaissance and often dug into the repertory of old master put all of his theatricality, heresy and provocation into his work as a painter.

More than 30 years after the extraordinary Salvador Dali retrospective of 1979-1980 at the Pompidou Center in Paris, when Dali (1904-1989) was alive but in ill health, Dali is back in an impressive retrospective running through March 25, 2013. The show examines his life, warts and all, and once again shines light on the power and the originality of his art, an art of technical perfection that culminated between 1925 and 1950, with a major boost coming in 1929 when he met Gala.

The exhibition opens with Dali in an Egg, a large photograph by Philippe Halsman that superbly translates the Catalan artist’s fascination with this symbol of intrauterine life and rebirth (renaissance). The egg is omnipresent in Dali’s work and it stands atop his home at Port Lligat and is repeated on the roof of his Theater-Museum in Figueres.

Among the 120 paintings in the retrospective are a number of works that are rarely shown in public along with many famous painting, including masterpieces from the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid and The Persistence of Memory (1931), also known as Soft Watches, the small painting on loan from New York’s Museum of Modern Art that is so emblematic of Dali’s universe.

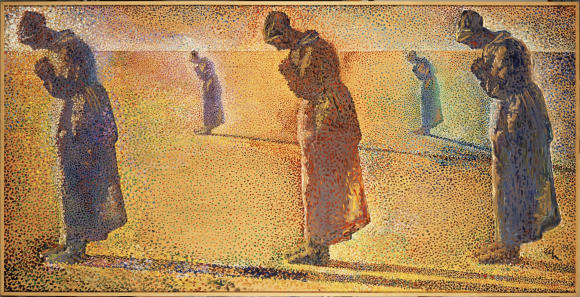

His method of “critical paranoia” is highlighted in the show, presented in such a way as to enable several levels of reading an image, as in his famous interpretation of Jean-François Millet’s painting The Angelus, which Dali returned to obsessively.

Adagp, Figueres, Paris 2012

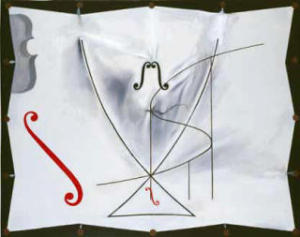

A wealth of drawings, objects, films and audio also contribute to a successful staging of the retrospective which includes kiosks and various theatrics (Face of Mae West Which May Be Used as an Apartment, with the possibility for visitors to actually sit on her couch-lips). Dali’s interest in performances and black-humor happenings is revealed, as when he plays a harpsichord in which a cat meows each time a key is pressed.

The retrospective examines at length the artist’s last twenty years of work, which are often disparaged. During that time Dali experimented with new approaches, for example pop art and action painting, which demonstrate his openness to the contemporary world even if the result isn’t convincing. He then returned to the old masters before finding inspiration in the mathematical theory of catastrophes. The genius had disappeared long before the end of the story.

Since Dali’s death in 1989, his abundant production has led to copies by forgers and reproductions on millions of posters and has served as a library of images and ideas for numerous artists: from Jeff Koons to Matthew Barney by way of Piotr Uklanski. Altogether these uses have troubled and even tarnished Dali’s image, leading me to give one piece of advice: Don’t miss this retrospective.

Dali Retrospective at the Pompidou Center, November 21, 2012 to March 25, 2013. The Pompidou Center is open daily except Tuesday 11am to 9pm. www.centrepompidou.fr. Entrance to the museum’s collections and exhibitions: 13€.

Catherine Rigollet is the founding editor of L’Agora des Arts, www.lagoradesarts.fr, a website dedicated to the arts. As a journalist she worked for Le Point, L’Express, Le Figaro Eco and the Les Echos group before taking over the culture and exhibitions section of Air France Magazine. She is the author of a dozen books about art, history, heritage and social issues including Les Conquérantes (Nil Editions, 1996) and Les Francs Maçons (JC Lattès 1989).

This article first appeared in French © Catherine Rigollet in L’Agora des Arts (see original article here) and has been translated and adapted, with permission, for France Revisited by Gary Lee Kraut.