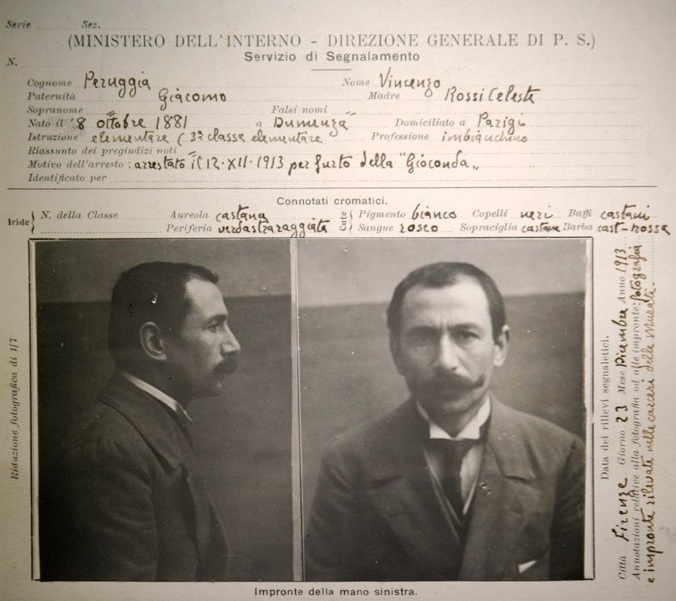

On August 21, 1911, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre by Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian laborer living in Paris.

Already one of the most famous paintings in the world at the time and the centerpiece of the French art collection for nearly 400 years by then, the theft of the Mona Lisa—known as la Gioconda in Italian and la Joconde in French—was a catalyst to its launch to superstardom as the global icon of art itself.

On August 21, 2011, the 100th anniversary of the theft, Joe Medeiros will screen his 88-minute documentary “The Missing Piece: The Truth About the Man Who Stole the Mona Lisa” to a select audience in Philadelphia, PA. (Subsequent to these early screenings, Madeiros changed the name of the documentary to “Mona Lisa is Missing.”)

I caught up with Joe Medeiros for the exclusive interview below as he was preparing for the event.

In the documentary, which I was able to preview, Medeiros carries out a thorough and fascinating investigation into the theft and into the life of the thief.

In piecing together pieces of Peruggia’s life, the documentary explains Peruggia’s arrival in Paris among a wave of Italian workers, tells how he went from a house painter to briefly have a job cutting and cleaning glass at the Louvre, describes in detail how he removed the Mona Lisa from the museum, shows where and how he kept the painting in Paris for over two years, examines his arrest in December 1913 in Florence, including the ensuing psychiatric report and trial, and tells what happened to Peruggia between his release from jail seven months later and his death in 1925.

Far more than a paper and painting trail, which would be absorbing enough, The Missing Piece is also a story about how his descendants view the crime, particularly his 84-year-old daughter Celestina, who never got to know her father directly since he died of a heart attack when she was only two. The filmmaker’s personal search to learn about Peruggia quickly becomes a quest to bring the truth to Celestina as to why, at age 29, her father stole the Mona Lisa. Since Celestina is too old to travel, Medeiros travels to Paris and to Florence with Peruggia’s grandchildren.

Joe Medeiros, a Hollywood television comedy writer by trade, spent 16 years as head writer for The Tonight Show with Jay Leno. He started out as joke writer from 1988 to 1992 when Leno was guest hosting for Johnny Carson. He moved to California in 1992 when Leno took over the show. Medeiros became co-head writer in 1993 and sole head writer in 1995, a position he held until May 2009 when Leno left the show for the first time. Though Medeiros never worked for Carson he did write jokes for Bob Hope from 1988 to 1992.

Now 60, Joe Medeiros has been shooting and editing his own short films since the early 1970s. He has also directed and edited the short documentaries Sailing the Star of India, Doors of Florence and Friends of Independence.

The Missing Piece: The Truth About the Man Who Stole the Mona Lisa is his first feature-length documentary. Currently in post-production, the film is being screened in Philadelphia on the 100th anniversary of the theft in part because Philadelphia is nearly Medeiros’s hometown—he grew up in nearby Bensalem, PA. His wife Justine has been actively involved in the documentary not simply by tolerating her husband’s passion for the subject over the years but, as the film’s executive producer, by making sure that all the details behind the camera are taken care of, that people get paid, interviews are scheduled, and the crew is organized. They have lived in Los Angeles for the past two decades.

Interview with Joe Medeiros

Gary Lee Kraut: Most people are underwhelmed when they see the original of the Mona Lisa for the first time. When did you first see the painting and what was your impression?

Joe Medeiros: The first time I was at the Louvre was in 1974 when Justine and I were on our honeymoon. The Mona Lisa … well, she wasn’t there. France had loaned her to Japan and the Soviet Union. She was making a tour of Tokyo and Moscow. So I was faced with the same empty space on the wall that visitors to the Louvre saw when she was stolen in 1911.

I saw her for the first time in 1977. A year after I got the idea to write a screenplay about the theft. She was behind bulletproof glass surrounded by crowds. I felt bad for her. She seemed to be a prisoner of her own fame.

GLK: That is the original shown at the Louvre, isn’t it? Are there any conspiracy theories that claim it’s a fake?

JM: It is the original as far as I know. I am not a believer in conspiracy theories.

GLK: How did you get interested in the theft of the Mona Lisa?

JM: It all began in 1976 when I read a sentence in a book about Leonardo da Vinci. On a page about the Mona Lisa, it said that ‘On August 21, 1911, an Italian workman named Vincenzo Peruggia stole the painting to take to Italy.’ I was immediately hooked. As a recent film school graduate from Temple University in Philadelphia, I thought this story would make a great feature film. So I did months of research into the details of the theft reading the newspaper accounts of the day and any book I could find about the crime.

JM: It all began in 1976 when I read a sentence in a book about Leonardo da Vinci. On a page about the Mona Lisa, it said that ‘On August 21, 1911, an Italian workman named Vincenzo Peruggia stole the painting to take to Italy.’ I was immediately hooked. As a recent film school graduate from Temple University in Philadelphia, I thought this story would make a great feature film. So I did months of research into the details of the theft reading the newspaper accounts of the day and any book I could find about the crime.

GLK: You’re film thoroughly examines the various steps of the theft. Can you give us an overview of how it happened?

JM: The painting disappeared on a Monday when the museum was closed. The theft wasn’t discovered until the next day because the Louvre guards assumed the masterpiece was with the museum photographer. There was a worldwide search that turned up more false leads than actual clues. Even Pablo Picasso was questioned for unknowingly having stolen statues from the Louvre in his possession.

All the time, Peruggia was living with the painting in a room in Paris about two miles from the Louvre. He had worked a short time at the museum for a subcontractor who was helping to cover 1600 masterpieces with glass. Peruggia was one of five workers entrusted with cutting and cleaning the glass.

As Peruggia worked, he became familiar with all the Italian art and wondered why it was in a French museum. One day as he was paging through a book, he read that Napoleon had looted Italy’s art treasures when he conquered that country and brought them back to Paris. Peruggia believed – wrongly – that all the Italian art in the Louvre was there illegally and he was determined to bring one picture back to its home country. The picture he chose was the Mona Lisa. He took her because she was small and easy to carry.

Peruggia kept the Mona Lisa in his tiny room in Paris and then in December 1913, brought her to an art dealer in Florence Italy claiming to be an Italian patriot. He was quickly arrested and the painting was soon sent back to Paris.

GLK: You said that you originally intended to write about the theft in a screenplay for a feature film. How did that intention develop into an investigative documentary?

JM: In my early research, I found many details about the crime and its investigation, but there was little information on Peruggia the man – who he was, what he thought and why he really stole the painting. So I was unable to write my script because I was unwilling to make up things about Peruggia. I wanted the truth. But he was dead and the Mona Lisa can’t talk, so where could I find it?

Thirty-two years passed, but I still wanted to tell Peruggia’s story. Then one day while Googling his name, I came across a magazine article about his 84-year old daughter Celestina who was living in the town where Peruggia had been born. So I went to see her with the thought that I could make a documentary about her father and that she would have the answers I needed.

She was a kind, charming woman – the type of Italian grandmother I always wanted. Unfortunately, she didn’t know much about her father because he died when she was a toddler. But all her life she wanted to know the truth. We both did. So I set out to find it.

This involved getting access to the original police files and court documents in France and Italy. We also found a critical piece of evidence – the report of the psychiatrist who interviewed Peruggia. With the help of a team of translators, I began to piece together Peruggia’s life story.

GLK: What was the most fascinating part of the research and investigations for you personally?

JM: I was fascinated by the psychiatrist’s report on Peruggia. It was commissioned by Peruggia’s lawyers to help with his defense and was performed by Dr. Paolo Amaldi, a leading Florentine psychiatrist of the day. It gave me quite a bit of information on Peruggia’s life history as well as the events that led up to him stealing the Mona Lisa.

Once I had that we went to the Louvre with Peruggia’s grandson Silvio Peruggia and re-traced the route his grandfather took to steal the painting. And in Paris, we found the apartment where Peruggia kept the painting for nearly 2 ½ years.

We then traveled to Florence with Peruggia’s granddaughter Graziella Peruggia. There we visited the hotel room where he was arrested and the prison where he was held. And in the Florence archives, we found the key to the mystery – the letters he wrote to his parents shortly after he stole the Mona Lisa.

In the letters we found what I think was Peruggia’s true motive for stealing the Mona Lisa. But it wasn’t what his daughter Celestina would want to hear. However I had promised to return to her with the truth and that’s what I had to do.

GLK: Did you discover any clues or facts that hadn’t been revealed before?

JM: From the documents I was able to piece together why I think Peruggia selected Monday, August 21 as the day to steal the Mona Lisa. It was a very deliberate choice. I don’t think that’s been mentioned. Also, how Peruggia got the painting out of the museum. Many people say he stuck it inside his workman’s smock. I show that that’s impossible. I also point out a medical ailment that Peruggia had that may have contributed to his two prior arrests. Also, that the psychiatrist’s diagnosis of Peruggia as ‘mentally deficient’ may have been an intentional exaggeration. Finally, we discover what Peruggia’s true motive might have been.

GLK: Where did Peruggia live in Paris and where did he keep the Mona Lisa for the 27 months before he took it to Florence?

JM: Peruggia lived at 5 rue de l’Hôpital Saint-Louis which is around the corner from where you live, Gary. I know that for his farewell dinner before he left for Italy he ate at a café on avenue Richerand. I wonder if it was the Café Richerand on the corner of Rue Bichat.

He said that he first kept the painting on a table in his room, and his daughter corroborates that. Several months after having the painting, he built a wooden crate with a false bottom to hide the painting in. He kept the trunk in a 6×6-foot closet in his room until he went to Italy.

GLK: There are many theories as to why Vincenzo Peruggia stole the painting and who his accomplices or sponsors were. Can you tell us in a nutshell your thoughts on why he stole the Mona Lisa and who was involved?

JM: I don’t want to reveal exactly why he stole it because that’s in the film. But I believe he stole the painting alone, although he did share information with his close friend Vincenzo Lancellotti who lived on the floor below him on rue de l’Hôpital Saint-Louis.

I can say that I believe Peruggia was convinced the Italian art in the Louvre had been stolen and that he wanted revenge against the French who had mistreated him. Returning the Mona Lisa to Italy was to be his ticket out of France to a better life.

GLK: Do you get in heated arguments with people who hold other theories?

JM: No. It’s hard to get into arguments with people over something that happened 100 years ago. But I do get somewhat miffed when people say that the theft was orchestrated by a mastermind—an Argentinean conman—to sell Mona Lisa forgeries. That “theory” came out of a 1932 magazine article by an American writer named Karl Decker. In our film, we discredit Decker and his story. There was no conman. Peruggia was the mastermind of the crime.

GLK: Whatever became of Peruggia?

JM: After serving 7 months of a 13-½ month sentence, he was released from prison. He joined the Italian army during World War I and became an Austrian prisoner of war. He was held for two years. After the war, there was no work in Italy so he was forced to return to France but went there under his given birth name Pietro Peruggia so that the authorities couldn’t trace him. He worked as a painter and died on October 8, 1925 from a heart attack. It was his 44th birthday. He was buried in France in the Parisian suburb of Saint Maur des Fosses.

GLK: After all your research and your encounters with Peruggia’s descendents, how do you feel about the man himself?

JM: I understand him now. He was a man who was tired of a job that was making him physically ill. He was put down by the French for being a foreigner and he missed his family and his home. For him the theft was a way to a better life. He had good intentions, just a bad way of achieving his goals.

GLK: How do you feel about the Mona Lisa now, compared to your first impressions which you told us earlier?

JM: She’ll always have a special place for me because of what I know about the man who stole her and had her for 2 ½ years. What he did is a part of her history. And what I’m doing in this film is a very small part of that history too. I’m proud to be associated in this very minor way with this great masterpiece. After all, if Peruggia had stolen any other painting, there would be no need to tell this story.

GLK: What are the plans for the documentary after the test screening in New York on August 17 and the screenings in Philadelphia on August 21 and 22?

JM: Once I have audience feedback from those two screenings, we will lock picture and have the final mixing and color correction done. Then we will start entering festivals and looking for an international distributor.

GLK: Are there any plans to show the documentary in Paris?

JM: I would love to show it in Paris as well as in Italy. We are working on possible screenings there in the near future.

“The Missing Piece: The Truth About the Man Who Stole the Mona Lisa” by Joe Medeiros. To see a trailer of the film and for further information the film’s official website.

(c) 2011, Gary Lee Kraut.

Comments may be left at the bottom of the page.

Postscript in French by Danièle Thomas-Easton who attended the Aug. 21 screening in Philadelphia. Danièle Thomas-Easton is the Director of France-Philadelphie, which provides consulting for French-American business and cultural projects.

Depuis la récente tentative de destruction d’un Matisse à la National Gallery of Art (par une récidiviste, qui plus est), la question est d’actualité: comment protéger les musées contre le vol, les dégradations ou tout acte de vandalisme? Malheureusement, le problème ne date pas d’aujourd’hui!

Si, en 1998, le vol d’un tableau de Jean-Baptiste Corot, Le chemin de Sèvres, survenu en plein jour dans la Cour Carrée du Louvre, avait provoqué une onde de choc dans le monde des arts (et des directeurs de surveillance des grands musées), que dire de la disparition, le 21 août 1911, de La Joconde? Une peinture sur un panneau de bois de 77 sur 53 centimètres, plus difficile à escamoter que la toile de Corot (24 x 37 cm.)!

Beaucoup d’encre a déjà coulé sur ce crime (presque) parfait. Il faudra en effet plus de deux années pour retrouver le tableau et arrêter le coupable en décembre 1913 à Florence. A l’aube de la première guerre mondiale, ce mystère captivera le monde entier et contribuera certainement à médiatiser l’énigmatique sourire de Mona Lisa. Plus tard, des cinéastes en exploiteront le thème (la comédie de Michel Deville, On a volé la Joconde, par exemple). On s’est peu penché cependant sur la personnalité du voleur, un vitrier italien qui avait travaillé au Louvre, Vincenzo «Leonardo » Peruggia, et sur ses motivations. C’est la lacune, the missing piece, que le réalisateur Joe Medeiros comble dans ce documentaire.

Présenté aux Etats-Unis dès septembre 2011 à l’occasion de plusieurs festivals de films, The Missing Piece apportera enfin à cette énigme de début de siècle une pièce à conviction inédite. Voilà donc le fruit d’un long travail de détective mené pendant trois ans par Joe Medeiros et son épouse Justine, qui leur aura permis, au fil de recherches entre la France et l’Italie, de retracer les pas de Vincenzo et de rencontrer sa fille, Celestina, et ses petits-enfants. C’est à Celestina qui n’a pas connu son père que Joe Medeiros avait promis de découvrir la vérité, toute la vérité sur l’affaire. Chose promise, chose due.

Really interesting, Gary! I’m passing the link to the article to the AATF Philadelphia Chapter.

Joanne Silver

Beach Lloyd Publishers, LLC

http://www.BEACHLLOYD.com

Thanks, Joanne!

Gary

I have been telling my middle school art students about the theories for Mona Lisa’s fame for years, yet didn’t know you had created a movie about it. Facinating! I can’t wait to view your documentary.

I am confused about the daughter. Vincenzo Peruggia is 84 now . but her dad passed away in 1925, and she was born in 1931? is she his grand daughter?

Sorry, I meant Celestina is 84 year. not Vincenzo Peruggia . But he died in 1925. An Celestina was born in 1931.

Pam.

This article was publish in 2011 shortly after Celestina Peruggia passed away, which I wasn’t aware of at the time. She was born in 1924, the year before her father Vincenzo died. Joe Medeiros first met and interviewed her in 2008, when she was 84. See Medeiros’s comments on her passing and video images of her here: http://monalisadocumentary.blogspot.com/2011/03/celestina-peruggia-1924-2011.html

Gary