Kings and soldier, emperors and rebels, nobleman and religious leaders, politicians and artists: the cityscapes of Europe are full of them. You see them high on pedestals, on horseback or standing tall in city squares, in parks, by government buildings, in front of churches. They may be proud, heroic, peaceful, dramatic, contemplative, or combative.

You don’t always recognize the name. But there he (less often she) is, some local hero, the memory of a moment, a community, a neighborhood, a city, a state, a region, or a nation.

Identifying and telling about the individuals or scenes such sculptures represent is the common stuff of tours. Most guides, whether a text or a person, will tell you who is represented in that sculpture, along with an intriguing or amusing anecdote or two.

The best guides—the rare guides—will also tell you when and why the monument was erected. There are as many insights to be learned by knowing who placed the monument as there are by understanding the social and political and perhaps financial context that brought about the monument and allowed that hero to be praised at that spot. For example, none of the royal sculptures that you see in the great squares of Paris date from the time of the represented king. The curious travel then asks when they were placed there. The wise traveler asks why.

For the group doing the honoring (i.e. paying for the monument), monuments to local heroes are a way of emphasizing a moment in history, writing—or rewriting—history, promoting an agenda, and honoring themselves for holding the views or carrying the supposed mantle of the person being honored. Napoleon III, for example, erected or re-erected statues of Napoleon I.

Unlike in Europe, where an informed visitor could get a great sense of a city’s history and major sights simply by going from statue to statue, far fewer figurative monuments stand out in the United States, though they do exist, particularly on the East Coast. Such monuments naturally appear more often in the nation’s older states because the honoring of public figures with a monument was far more common in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The monument to a public figure, whether financed publicly or privately, lost favor in the 1960s as the will to promote and finance such projects was often resisted. For a while cities and states were conscientiously attaching the names of favored sons to buildings and parks; mostly now those honors go to donors and advertisers.

Even on the East Coast, only a handful of cities have felt the need (or had the political or community drive) to honor their local heroes in marble or bronze. Richmond, Virginia, is one such place, which is why I had such an enjoyable sense of European-style discovery there recently while examining the city center’s many monuments to local heroes and asking Richmonders about them.

They may be forgotten heroes, they may be heroes of another era, or they may be heroes only of those who held influence at the time the statue was erected. In any case, there they sit or stand in the heart of Richmond:

on Monument Avenue

– Robert E. Lee, J.E.B. Stuart, Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson, Matthew Fontaine Maury, Arthur Ashe;

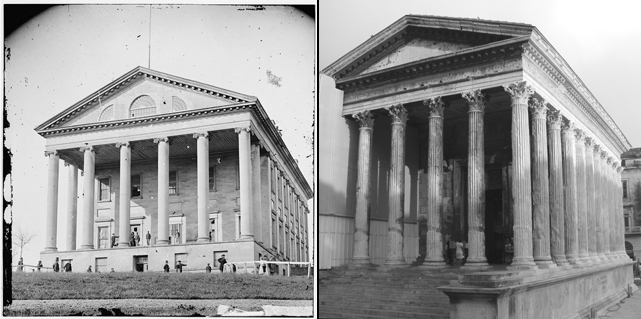

outside the Virginia Capitol

– Harry F. Byrd Sr., George Washington and fellow patriots, Governor William Smith, Stonewall Jackson (again), Dr. Hunter Holmes McGuire, Barbara Rose Johns and others on the Civil Rights Memorial, Edgar Allan Poe;

inside the Virginia Capitol

– George Washington in the rotunda surrounded by the busts of the seven Virginia-born presidents who served after Washington: Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, and Woodrow Wilson. And since that leaves one other niche in the octagonal space, the bust of Marquis de Lafayette fills the eighth. Meanwhile, in the Old Hall of the House of Delegates, Robert E. Lee turns his back to George Washington as takes up the fight of the Confederacy.

As a Northerner, I was fascinated by the many monuments to leaders and heroes of the Confederacy. Asking around I learned that construction of monuments to men of the Confederacy in Richmond, as elsewhere in the South, derived from the same form of nostalgia and political strength as monuments to, say, Napoleon in Paris or churches of the Counterreformation. I leave you to investigate that nostalgia or strength on your own. Ask around when you come to Richmond.

Instead, I’ll jump to my purpose for writing today about this stop on my East Coast road trip: local Francophilia.

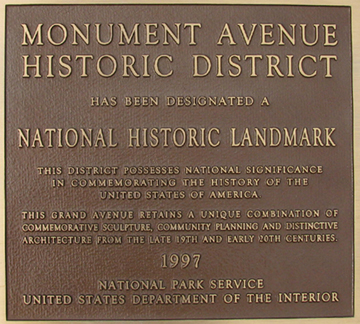

The friendly folk at the welcome desk to the State Capitol were so willing to guide me in my search for local Francophilia that I nearly overstayed my coins in the parking meter. We discussed how Jefferson, in designing the original Capitol in the 1780s (the central portion of the current building, before it sprouted wings), was inspired by the Roman temple known as the Maison Carée in Nimes.

Those proud Richmonders actually found and photocopied a leaflet for me noting various French connections in the Capitol Square. Due to Jefferson’s French connections and Francophilia, Frenchmen were involved as consulting architects, draftsmen, and scale model makers in planning the building’s construction.

The sculptures of Washington and Lafayette in the rotunda are the work of French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon. Both are made from life masks that Houdon made of the men. Houdon was recruited for the Washington job by Jefferson himself who was then in Paris. The marble bust of Jefferson, copied from an original by Houdon, was presented to the Commonwealth of Virginia by a committee of French citizens in 1931. A bronze copy of the famous Washington statue was presented by the Commonwealth of Virginia to the Republic of France, specifically to the Museum of Versailles, in 1910.

Lafayette, Virginia’s first honorary citizen by act of the State Assembly, visited the Capitol in 1824 during his tour of the United States celebrating the cause of the American Revolution and his role in it.

Between touring Monument Avenue and the State Capitol I enjoyed driving along the center-city grid and seeing the magnificent old mansions.

I also visited the commercial Uptown and Carytown sections. Carytown, along and around Cary Street, was my main point of attack because I wanted to have breakfast at Jean-Jacques. I’d been told by a Francophile working at one of the city’s museums the Jean-Jacques was Richmond’s premier French bakery. (Where you visiting from? she’d asked. Paris, I’d said. The rest was history, and no parking meter to worry about.)

The entrepreneurial Jean-Jacques who launched the business left the eponymous bakery and café long ago, but Jean-Jacques has stayed as its name because there’s no denying that Jean-Jacques sounds French… far more than Josef, first name of the head chef since 1985 and owner since 2006.

Josef Bindas grew up in Belgium and traveled the world for many years before finally settling in the Virginia capital, yet his roots in French baking, and more particularly northern French baking, are deep and strong. His daughter Liliana now assists as manager and wedding cake expert.

There’s an appealing earnestness to the way he describes his work, his use of French equipment, and his insistence on importing as many fresh products (cream, butter) as possible from France. I sensed his integrity as a baker and as a businessman, the desire to appeal to local tastes without betraying his own sense of quality French baking.

When visiting a bakery in the morning, as I did here, I invariably first test the croissant. Spoiled by butter-rich Paris croissants, I would have liked Josef’s croissant, fresh though it was, to be more flaky and buttery, but it was quite nice for dipping in coffee.

I went for the calories on my next selection, a strawberry allumette—a puff pastry with strawberry, almonds, custard, and whipped cream. I already liked the place, and that pastry made me like it even more, earning Josef and his Francophile shop high marks from this writer.

I call it a Francophile shop not just for the offering and the equipment but because during my visit time several French-speaking clients and friends of Josef stopped in for a morning chat. There’s a long bakery counter and a half-dozen tables here. Nothing extraordinary, but I liked the feel of the place and Josef’s attitude toward his work and his clientele.

There’s a handsome French brasserie on the other side of the parking lot called Can-Can (or Can, as the half-lit sign indicated when I found when stopping by in the evening). You might also consider this, as I did, for an evening wine stop. Nice atmosphere, even on a calm night.

A more intimate and more upscale French restaurant 1 North Belmont, whose name echoes its address, is around the corner.

Meanwhile, on the western edge of the city Frenchman Alain Lecomte has an excellent reputation for classical French cuisine at his restaurant Chez Max.

I said to Josef, “Let me get this straight: there’s French restaurant called Chez Max run by a guy named Alain and a French bakery called Jean-Jacques run by a guy named Josef. Don’t you find that a little strange?”

“C’est comme ça,” Joseph said with a Gallic shrug—that’s just the way it is.

– Text and photos (except Library of Congress photo) GLK.

* * *

Addresses, etc.

Jean-Jacques, 3138 West Cary Street. http://www.carytownbakery.com/

Chez Max, 10622 Patterson Avenue. http://www.chezmaxva.com/

Can Can, 3120 West Cary Street. http://www.cancanbrasserie.com/

1 North Belmont, 1 North Belmont, http://www.1northbelmont.com/

The Capitol is open to visitors Mon.-Sat. 8:30 a.m. – 5 p.m. and Sun. 1-4 p.m. Guided tours are given regularly and self-guided tours are also possible. See http://www.virginiacapitol.gov/ for more.

I really enjoyed reading this article! I’ve been living in Paris for over a year now, after 15 years in Richmond Virginia. I wish I had learned more about the connection between France and Richmond before I left my beloved RVA for Paris, but I will have a lot to discover about my city whenever I return. Loved your insights, thank you!