For many people, both French and foreign, something uncomfortable lurks in the name Vichy.

Vichy calls to mind first and foremost the provisional French government of the years 1940-1944 that collaborated with the Nazi Germany occupation of France. Or as an American I met upon returning to Paris from a two-day stay in the town Vichy put it, “Didn’t something bad happen there?”

Only rarely does Vichy evoke an actual, living town, one that even the French would be hard-pressed to find on a map. Yet come to Vichy (pop. 28,000) in the center of France, just under three hours by train from Paris, and you’ll soon have in mind not the waste and manipulation of war but rather the echo of one of the great pre-war spa towns of Europe.

Though now far from the European routes of high fashion or popular dreams and nearly lost in the beefy, little-visited mid-section of France that is the Auvergne region, Vichy still reveals in bold and hidden details the leisurely splendor of a spa town that was all the rage from the summer of 1861, when Napoleon III gave it his imperial stamp of approval, to the fall of 1939, when Europe geared up for war.

It was that thriving spa town and its then-modern facilities that incited the French government in 1940 to call this their temporary capital.

Blitzkrieg, Armistice, and the Occupation

During the German Blitzkrieg into northern France in the spring of 1940, the French government originally fled to Bordeaux from Paris. In June, France signed an armistice with Germany. With that, the country was formally divided into the Occupied Zone, which comprised northern France and the length of the Atlantic Coast, and the so-called Free Zone, which compromised the rest, with the exception of the southeast corner of the country which was occupied by Italy. Since Bordeaux was included within the Occupied Zone, the French government had to find a provisional capital within the borders of the Free Zone.

For a government in search of a home, Vichy in 1940 was a natural selection. It offered an ideal location in that it was situated within the Free Zone and in the center of the country. It offered an extensive modern infrastructure and communications system—by air, by rail, by telephone, as one would expect of a top-of-the-line resort town—and had nearly 250 hotels (compared with 30 today), many quite large, that could be requisitioned for government purposes.

The government arrived on July 2, 1940. The luxurious Hotel du Parc was selected as its headquarters. For the next four years, tens of thousands of year-round government workers would eventually replace the seasonal spa-goers.

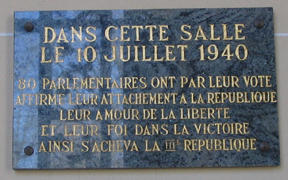

A plaque inside Vichy’s opera house indicates that it was there that on July 10 the National Assembly voted full power to Field Marshal Philippe Pétain, thus ending France’s Third Republic.

It actually says it the other way around, stating that 80 members of the National Assembly (out of 649) voted to “affirm their attachment to the Republic, their love for freedom, and their faith in victory [over Germany].” Notice the way in which the small minority are applauded rather than the vast majority condemned. Either way, it was here that was created what became known as the Vichy Government.

Although the German army didn’t physically occupy the Free Zone, the French government collaborated with German powers in an echo of the latter’s policies in the north, particularly by allowing like-minded militia, supplying the Germans with forced labor, and interning Jews and dissidents, eventually handed over to the Germans.

As significant as that plaque is, one doesn’t come to Vichy to contemplate the war years. The Vichy of “Vichy France” and “the Vichy Government” is better understood elsewhere.

The Vichy of splendor, luxury, and well-being, on the other hand, is best understood by entering the theater where that vote took place. There you won’t find memories of war but rather the full radiance of one of the most stunning Art Nouveau theaters anywhere.

Indeed, visiting Vichy today doesn’t mean forgetting its association with a sullied wartime government but rather recognizing it and moving on—or back. That’s because the true interest of a 24-72-hour stay in Vichy is the architecture and the pleasure of walking around its small, languorous center with eyes wide open for details, or shut, perhaps, as you lounge in a warm, bubbling bath of spring water.

Napoleon III and the development of a major spa resort

Vichy’s town’s development over the past 150 years has left structures and details that reveal four major periods of architecture and urbanism: Napoleon III (1860s), Art Nouveau (1895-1903), Art Deco (1925-1935), Contemporary (since the late 1980s). Each period has modernized the infrastructure, technology, comfort, and architecture of the town.

It’s those details, and the general sense of well-being in this town, that can entice a traveler off the beaten track of major highways and high-speed train routes to spend a day or two or three in Vichy. Before taking the waters, however, let’s step back 150 years.

In the 1850s, Vichy was a small budding spa resort. Its hot springs attracted visitors as did others in the region that had been known since Roman times. Then in July 1861 Napoleon III, emperor of France from 1852 to 1870, come to visit. He came to find relief from his rheumatism, and by the time he left, feeling better, he signed a decree throwing his full imperial weight behind the town’s development, both for his own annual pleasure while taking the waters, i.e. la cure, and to create an economic rival to the great 19th-century spa towns to the east, such Baden-Baden in Germany. A town of leisure and luxury began to grow immediately.

Boosting Vichy’s place on the map in the 1860s naturally implied the construction of a new train station, now the town’s old station, which has been restored, and urban planning in the streets radiating from the train station to the hot springs, a distance of about a half-mile that is the commercial heart of the town.

A row of chalets on Boulevard des Etats-Unis (formerly Avenue Napoleon III), including the emperor’s home, also date from the Vichy’s imperial era. Among them, Chalet Eugenie was built for Napoleon III’s empress but she never stayed here. In fact, she spent only ten days in Vichy. Soon after arriving she discovered that her husband had also invited his mistress to Vichy and she promptly left the town, never to return. While Napeoleon III sojourned at Vichy each year from 1861 to 1865 for about 4 weeks in summer, then for ten days in 1866. Eugenia preferred to take the waters at Biarritz. He might have returned again in 1870 but he was kept away by the developing conflict with Prussia, which led to the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War (July 19), and the fall of his regime (September 4). He was exiled to England, where he died in 1873 and is buried.

The entrance to the casino (photo above), now the convention center, is among the most emblematic of the architecture finery of Vichy because jutting out from its Napoleon III façade, a sign of its first golden age, is an airy Art Nouveau glass canopy added in 1900, a sign of its second.

Art Nouveau

The most stunning example of Art Nouveau, however, is the adjacent theater/opera house, mentioned above, inaugurated in 1902. The exterior, even cleaned, would get mixed reviews, but the ivory, yellow, and gold interior of the 1400-seat theater so exudes a sense of leisure and the leisure class that, show or no show, one could easily sit here for a couple of hours, without intermission, though perhaps a little nap.

Vichy is in fact a great place for a nap. In fact, from the emptiness of the streets during my April visit I wonder if the Vichyssois spend much of the day, not to mention the evening, napping.

Vichy’s central park, Parc des Sources (park of the springs), lies between the Casino/Opera/Convention Center and the central building where medical spa-goers and non-medical visitors can come to drink a dose of Vichy water. Covered walkways border the triangular park leading between the two. The walkways are at a reminder of a time when taking the waters at Vichy required little more effort that strolling between the spa, the casino/opera, and a hotel bordering the park. Even today one can enjoy a stay in Vichy without venturing more than 500 yards in any direction from the Parc des Sources.

Only several of the rooms from the high luxury spa area as originally decorated in the former first-class spa complex circa 1903, the Thermes du Dome, the thermal baths of the dome, remain intact.

The Thermes du Dome had a men’s wing and a women’s wing, and each wing had at its far end two grand luxury suites consisting of a dunking pool, a bathroom, and a lounge room. We visited a suite in the men’s section with its old tub and dressing room surrounded by white tiled walls painted with beautiful Art Nouveau irises that only the crème of the crème of spa-goers got to see back in the day.

The central portion of the complex, beneath the dome, is open to the public, so visitors can freely see the wonderfully serene mural painting at the entrance to what used to be the women’s wing and what now mostly resembles an abandoned warehouse.

The Thermes du Dome are no longer in use as a spa, however the active spas are all nearby. As far as its water and spas go, Vichy is, for better or worse, a company town, with the Compagnie Fermière de Vichy, which has existed since Napoleon III’s time, holding the concession from the French state. The Compagnie Fermière has joined forces with the Accor Hotel Group to exploit the three main spas and their adjacent hotels in the center of town. The 3-star Novotel-Thermalia complex is just behind the Thermes du Dome and partially integrates another building from 1903. The 4-star Sofitel-Célestins complex is a few hundred yards away, while the 2-star Ibis-Callou complex nearby in the opposite direction.

Despite the Art Nouveau purity of some turn-of-the-century building in Vichy there was a lot of neo-whatever going on between 1880 and 1914, hence the playful variety of style of villas on the streets one and two blocks off the Parc des Sources. Boulevard de Russie, rue de Belgique, and rue Hubert Colombier are the best example of this.

Many of the great palace hotels of Vichy were built, transformed, or expanded during this period, the town’s second golden era. A sign of their respective times in a resort town, a racetrack was built in 1882 and, to please and draw British visitors, a golf course was created in 1908. The only palace still functioning as a hotel is the 4-star Aletti Palace Hotel (1908). Venture in whether staying there or not. (The others have been transformed into apartment or office buildings and, aside from the occasional glimpse of grandeur in the lobby, can only be visited from the outside. The best way to visit their interiors is with the coffee-table book Palaces et Grands Hôtels de Vichy by Jacques Cousseau (Editions de la Montmarie, 2007.)

A five-minute walk from the Parc des Sources, near Lake Allier, gurgles the spring known as the Source des Célestins. It’s freely open to the public and is the best place to fill your water bottle before enjoying a stroll along the lakeside promenade.

Art Deco

Contrasting with the arches, curves, and floral aesthetic of Art Nouveau, which flourished wherever money did in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the streamlined grace of Art Deco developed in the 1920s and to the late 1930s, at which point aesthetics themselves were decimated in Europe. Vichy fully embraced the new style while leaving its older buildings intact.

Just as Vichy’s opera plays the tune of Art Nouveau, a sweet little 470-seat theater (now part of the Centre Culturel Valery Larbaud) several streets away opens the curtain to Art Deco. Among the most appealing Art Deco details in Vichy are here: three stained glass windows (Francis Chigot, 1926) representing Comedy, Music (or The Orchestra), and Tragedy, placed by the stairwell to the theater.

In the same theater here’s an image of bathing women that’s worth comparing with the Art Nouveau-era image of bathing women as seen above at the Thermes du Dome.

Eglise Saint Blaise , in the same quarter of the city, also takes Art Deco as its article of decorative faith.

Art Deco villas dot the town, mixed in with villas and hotels from earlier periods. Built on the same street as Napoleon III’s chalets, the Art Deco villa shown to the left served as the American embassy to France from 1940 to 1942. The street is named Boulevard des Etats-Unis (Boulevard of the United States), a name that it had prior to the war and managed to maintain despite the conflict. It’s strange to imagine that the U.S. had an embassy in Vichy, even once the U.S. and Germany were officially at war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Relations with the Vichy Government, never very direct in any case, degraded through 1942, until Vichy cut diplomatic relations with the U.S. in the fall of that year.

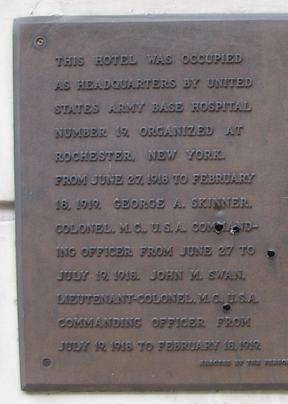

In the center of town there’s a plaque indicating that an American military hospital was set up there in 1918, to care for the wounded well away from the front of WWI. It is ridden with bullet holes, pot shots taken by French militiamen during WWII.

You want the dark side of Vichy, you can find it.

But the traveler comes away from Vichy not with a sense of its dark side, but rather of its easy, languid light: of imperial development, of Art Nouveau splendor, of Art Deco grace, of warm, soothing baths, long, slow promenades, and a pleasing sense of discovery.

© 2009, Gary Lee Kraut

Further information

Though this article concerns the sights, spas and theaters of the heart of Vichy, it’s worth noting that the number one draw for visitors to Vichy is its installations for sports training, with national basketball, rugby, soccer, and fencing teams among those training at Vichy’s Parc Omnisports, on the opposite side of Lake Alliers from the center of town. A racetrack A racetrack and golf course also border the lake.

The development of the sporting industry in Vichy began in the late 1960s as a response to the dramatic decline in the town’s attraction as a resort destination. The jet set clearly preferred the Riviera. (From nearly 250 hotels in 1938 there are now about 30). Business meetings rank second as a draw for visitors, with the spa installations ranking only third. And few leisure travelers stop by for a simple discovery stroll of a day or two or three. Consider yourself privileged then if you do. The “season” per se is said to be April to October, but you may well have the place for yourself through most of April, May, and October.

– Inhabitants of the town of Vichy are the Vichyssois

Vichy Tourist Office: www.vichy-tourisme.com

Accor Hotels (see comments in article): www.destinationvichy.com

Aletti Palace Hotel (see comment in article), a Best Western affiliate: www.hotel-aletti.fr

For pastries and sweets:

Aux Marocains, a chocolate and candy shop established in 1870, 33 rue Georges Clemenceau. The shop’s colonial-era name is also that of caramels with a soft caramel interior and a harder caramel exterior that have been made here since at 1920.

Aux Marocains, a chocolate and candy shop established in 1870, 33 rue Georges Clemenceau. The shop’s colonial-era name is also that of caramels with a soft caramel interior and a harder caramel exterior that have been made here since at 1920.

Au Poussin Bleu, bakery and pastry shop, 15 rue Lucas.

Most of the shops, cafés, restaurants, and pastry shops gather within the half-mile between the train station and the Parc des Sources.

– Supporters of the Vichy Government were called Vichyistes

Diplomatic relations: For an official U.S. summary of French-American diplomatic relations since 1776, including the Vichy period, see this page history.state.gov/countries/france from the site of the U.S. Department of State.

La France Divisée (Divided France) is a video exploring collaboration and resistance in Vichy France as told in 2002 by survivors, historians, and a Resistance leader. Though not an in-depth exploration, the 36-minute video is a worthwhile teaching tool for teachers of both French and history, especially at the high school and freshman-sophomore college levels. It was produced and directed by Barbara Barnett and Ellen M. Angelini, teachers of French in the United States. See www.francedivided.com for more.

Other Vichys

A brand bottle of sparkling mineral water, of throat lozenges, and of beauty products.

A checkered (gingham) fabric, often used for a tablecloth

Vichyssoise, a cold leek-and-potato soup thickened with cream.

Vichy carrots, long-cooked in Vichy water. Add butter, parsley, perhaps a bit of sugar—et voilà.