Laurent Cantet’s film The Class (Entre les murs) won the prestigious Palme d’Or at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, earning high praise for its lively portrayal of adolescents in a Parisian high school, and is now France’s official entry for the 2009 Oscar in the Foreign Language Film Category. Rather than create a stilted picture of youth, the film gives a startling vision of the real energy of thirteen-year-olds.

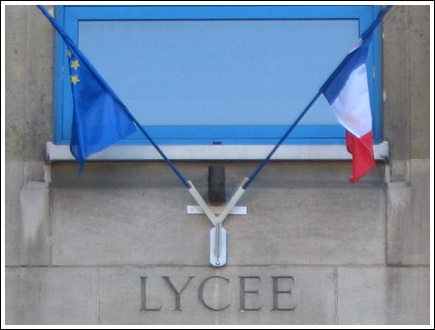

To make this film Mr. Cantet set up a real class of disparate adolescents in a high school in Paris’s 20th arrondissement. They improvised together for one year in a workshop-like environment with no set dialogue, creating an atmosphere that allowed the students’ own language and impulses to flourish. The first shot: girls and boys tapping their feet, eating pencils, putting their heads in their lap, hitting their neighbors.

Many journalists applauded the originality of the docu-fiction approach. As film critic and film teacher working in French higher education for the past ten years, my own interest in the film was more particular: in how this portrayal of a classroom exposed specifically French ideas of what it means to educate youth and in what ways those ideas clash with my life growing up in the United States.

To my American-educated eye the teacher in the film, lauded as a “Dead Poets Society” champion to these kids, appears to be disturbingly conservative in his ironic, authoritarian approach. Despite his wit and spark his French rigor shines through. In an early scene, a student objects to the fact that no multi-cultural names are used in sentences on the chalkboard: why is everyone always “Bill” or “John” rather than “Rashid”? The teacher quips: “Do you know how difficult it would be to represent all of your cultures?”

Indeed, The Class, despite its intentions to show dynamic pedagogy at work, reveals the opposite: how learning for the French still consists of accumulating facts: basic mathematical and linguistic skills; points of geography and history; the properties of a triangle. A poem is discussed in terms of its meter. At the end of the school year, the teacher asks each student to say what she or he has learned that year. Each comes up with a fact, so badly learned (i.e. “if the square of two sides of a triangle equals the hypotenuse, this means it is a square”) that the film seems to be mocking its pupils. The facts are divorced from any wider perspective, each as individual as a lone petit-four on a tray.

As a sociological document, the film underscores how the French educational system—even today—is based on the idea that one does not educate students (i.e. lead them, as in the etymological root of the word) but form them as in a mold.

I get these “formed” students in my own university classes: silent as sheep, scared, hesitant to offer original ideas, but extraordinarily well-versed in facts, awkwardly polite, and exasperatingly docile citizens of the classroom. It is telling that the climax of Cantet’s film is a disciplinary problem. A boy is kicked out of school and forced to go back to Mali because of an outburst in the classroom.

The film also makes conspicuous a more alarming and yet subtle feature of the French system: there is no pretense in social mobility for those who are not born of the native white French upper class. A black student hesitantly notes that his mother, a non-French speaking African, would like him to go to the prestigious Henri IV high school. The teacher grins.

The scene is intended as a joke.

When I interviewed the director of the film to find out what he thought of elitism in the French educational system he told me candidly, “A professor cannot speak the same way to a mother who does not speak French as he does to a student heading for the grandes écoles [the most prestigious universities on France]. The mission of a professor is, on the one hand, to help students gain knowledge like math and geography and history, and on the other, to help them become adults. Education has the aim of domestication, to help create intelligent, balanced social beings and citizens. The professor has to tame these teenagers.”

It seems a retrograde idea of education to have “domestication” of students as its principle—or to assume that a teacher must speak differently to an African mother than to a French mother. And yet what seems retrograde to me, as an outsider, may be radical for the French. Francois Bégaudeau. The actor who plays the teacher in the film and the real teacher who wrote the book upon which “the workshops” were based, opined that French schooling is far less conservative now than it once was. For him, the French educational system today is much better than it used to be when he was a boy in the 1980s and felt terribly bored. At least in today’s classroom, he says, the teacher can spar and interact with the students, create lively situations, provoke them. When he taught (he has retired since becoming a writer), he did everything he could to make sure students were not bored.

“For me, when I saw students’ eyes shine, I knew I was doing my work.” He personally opted not to teach classics such as Molière as these were references that had nothing to do with his students’ reality. “It’s scandalous that kids today are bored,” he added animatedly. “That 25% of French students polled would prefer to not go to school.”

As for my perspective that his own attitude was authoritarian: “No, the students love the sparring. Most of my interactions with students are these fun conflicts: it’s a game to see who will get the last word.”

Getting the last word is not a game high on my (again American-trained) pedagogical agenda. That underscores the cultural divide.

It’s the same cultural divide that heard echoed in reactions to the film “The Class” by other journalists at the Cannes screening. “What a great film,” a French Belgian journalist said on the way out. “It shows how hard it is to be a teacher today, to discipline these kids.”

And as though he’d just come from a different film, an Anglo-Canadian journalist said to me at the press coffee bar: “A great film. Shows how oppressive the French school system still is. Everyone has to fit in, or they’re out. Look what they did to that boy from Mali!”

The Class does indeed show two important aspects of the French school system: that forming children in the mold is its baseline approach and that critique is not coming from within.

Karin Badt is an American film critic, fiction writer, and film and theater professor. She has a regular blog at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/karin-badt.