Only an expatriate can understand the pleasure of returning home without having to be someone’s guest. There’s no place like home, of course, and there’s no freedom like being there alone.

We are so accustomed to being visitors when back in the U.S. that however warm the welcome of family or friends we sometimes want them to go away for a few days. So, having dropped my dear mother off at the airport where she would board the snowbird flight to Florida, I drove back to her house in New Jersey thinking how much I was going to enjoy the next four weeks. It isn’t that I was planning on running around naked or throwing parties, but, well, if there was a time to run around naked and throw parties this would be it.

To make matters even more promising, the threats of winter that had led my mother to flee south never materialized. The weather remained so unseasonably mild that on the afternoon before one of the aforementioned parties I went out and did something I don’t get the chance to do in Paris: yard work. Saw and clippers in hand I roamed the yard like a mass murderer out for exercise, cutting overgrown branches and vines and plants that may or may not have been weeds.

When my friends came over for dinner that evening it was too dark out to see the very neat property line I’d left in my wake, but they did notice a red spot on my neck and, by the end of the evening, another spot on my forehead.

By the next afternoon I was well on my way to sporting a horrendous case of poison ivy, the likes of which I hadn’t known since a teenager.

Poison Ivy

Poison ivy isn’t easy to explain in New Jersey in December and it’s even more difficult to explain in France since it doesn’t exist here. PI is so commonly associated with “three leaves let them be” that it was easy (for me) to ignore that the dangerous resin is also present in the vine, which is where I went looking for it. Furthermore, the weather was so pleasant that rather than shower or change after cutting the vines I continued to do all of the otherwise harmless activities that one turns to after a couple of hours in the yard, such as going for a walk, rubbing one’s neck, talking on the phone, tugging at one’s waistband, and peeing.

For the next four days I lived like a miserable optimist, believing each day that the rash couldn’t get any worse, only to discover the following day that it had. I withdrew from the world like a leprous hermit in woolen underwear and stayed that way for a full week. I ventured off the property only to send an urgent package at the post office, where the normally tight queue of the Christmas rush stretched out to either side of me like an old Slinky as people looked at me—rather, tried to not look at me—as though I were the Elephant Man. The generally kind postal workers at the West Trenton post office typically make their French counterparts look as though the latter had just collectively learned that they suffered from incurable cancer. But this time the postal worker who had the misfortune of having me approach her counter took my package as if I’d written “ANTHRAX” instead of “FRAGILE” on the wrapping.

Staying inside all day might have been the perfect occasion to write articles from the research I’d done at Versailles prior to leaving Paris, but each time I sat at the computer to describe Marie-Antoinette’s private palace I found myself staring wretchedly at the bubbles on my arm, unable to do anything but google “poison ivy” and eventually click on all 1,370,000 results.

After I had eaten all of the veggie burgers, broccoli heads, low-fat waffles, and Egg Beaters in my mother’s freezer, which go surprisingly well together if you add enough teriyaki sauce, and reluctantly thrown out various packages ominously stamped “best if used by Feb 1996,” my sister Lesley began delivering food to my door during her lunch break—and immediately excusing herself for not staying because she had, um, an important meeting. Carin, my other sister in New Jersey, never made it over because she said that just talking to me on the phone made her itch, which isn’t good for the morale of someone who normally lives 3000 miles away.

Sciatica

After a week of calamine, steroids, and self-pity the rash on my neck and face had cleared up enough for me to go out in public again without shocking anyone, as long as I was discreet about scratching myself under my clothes. I then had several very nice days during which I was able to catch up on the dinner invitations I’d had to postpone, go to a cozy new year’s eve party, and, the weather still being mild enough, play tennis outside. In fact, the steroids I’d taken the previous week to get down the PI swelling on my face seemed to be doing wonders for my tennis.

That, a doctor told me a week later, may be what laid the ground for my sciatica pain. I felt a first twitch at the base of my spine while hitting a glorious crosscourt backhand one afternoon. At first the discomfort may have been partially masked by persistent PI itch along my waist band, but it increasingly announced its presence before changing names to outright pain that shot down the back of my leg. Once again I was certain each day that it could get no worse, until the next day proved me wrong.

The pain turned into an endless cramp that was so bad that Lesley, who had now been delivering drugs along with the food, drove me to the emergency room at 4am on a Saturday night. After that, having befriended Percocet and cyclobenzadrine, I lay semi-conscious on her floor for a few days while her 2- and 3- year-old children gleefully stomped on my head, so happy they were that Uncle Gary had come all the way from France to play.

Between December poison ivy and tennis-encouraged sciatica, I need no further proof that global warming will indeed affect us all in unexpected and dangerous ways.

After a week of doctor visits and medical tests I learned that the root of my suffering was a herniated and degenerated disk, which sounds like something one would buy in Paris. I had to postpone my return flight twice because of the tests and treatment (finally had an epidural cortisone shot) and because an overseas flight in coach is bad enough without nerve damage.

HIPAA

I hadn’t had much encounter with the American medical system in a while so these medical visits were my first experiences with HIPAA, the national health information privacy standards adopted in 1996 and in full effect since 2003.

One of the quirks of HIPAA is that you should be called by your first name in the waiting room so as to guard against the invasion of privacy that would come from other patients being able to identify you through your last name. Such a policy in France would be in direct contradiction with its cultural policy of formal distance, where one would be justly horrified to hear one’s first name being used in such a serious setting.

As Americans we are already accustomed to having everyone call us by our first name, so I think the medical first-name policy is just a way of codifying our natural tendency to buddy up to each other for brownie points. Indeed, there seemed to be no similar discretion when I was repeatedly asked to give aloud my social security number in a crowded office or when one receptionist called across the room, “Gary, are you on any other medications right now?” No, I called back, but I could use an anti-depressant.

The Human Voltmeter

Living in France, I have private, European health insurance that serves as a supped up version of France’s national health care system, meaning that my medical expenses in France are mostly reimbursed or paid for directly by the insurer. When in the U.S., however, I must pay upfront for all medical expenses then hope that I’ll be reimbursed once in France. In other words, I’m treated in the U.S. as being among the legion of the uninsured.

I come from a family of doctors, so I won’t spit on the price of American medical care. I nevertheless found it astonishing to be told upon entering one office that I would have to pay the $500 bill upfront and in cash. This, apparently, is the special price reserved for “uninsured” visitors since insurance companies are unlikely to accept such a price. In announcing the price, the receptionist wasn’t the least bit phased that I didn’t have $500 in cash on me; she gave me a sympathetic look as though I’d told her that I’d left home without having breakfast and gave me directions to the WaWa a mile up the road, where I could find coffee, muffins, and an ATM.

The C notes were for a 10-minute test that involved having my leg poked with an electromyogram, which is simply a human voltmeter and relatively cheap as far as medical equipment goes. In order to get me a quick appointment my referring doctor, a friend, had informed the electrician, uh, physician that I live in Paris. So as he zapped my leg the physician told me about his various trips to Europe, the luxury hotels where he’d stayed, the famous restaurants where he’d eaten, and the cases of wine he’d shipped home.

Now, it is a commonly known cultural tidbit that we Americans are quick to talk about ourselves and about money while the French flee self- and financial revelation like the plague, but one would think that the guy could interrupt his Condé Nast narrative to feign interest in something other than my nerve endings. Yet the more significant insight in this experience was my realization that his discourse was actually part of his job since a doctor who can show that he has expensive tastes is apparently considered more trustworthy than a doctor who cannot. Who would want a doctor who’s never been to Paris, anyway, or at least Cancun?

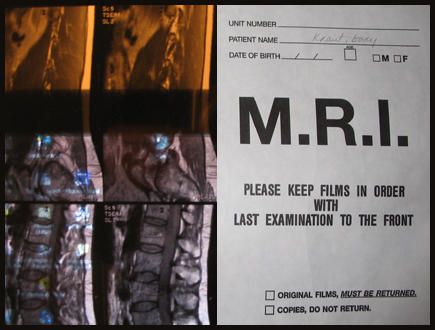

The MRI

Seven years ago I had my first MRI and discovered that I don’t like being placed in a coffin. I only made it through the ordeal because breaking into a claustrophobic sweat was new to me then and because I believed the technician’s reassurance that it was “almost done.”

Two years ago I had a second MRI in Paris for an injured tendon in my hand and knew better. That MRI required no more than sticking my arm into the tunnel with my head barely inside, nevertheless I thought it necessary to tell the French technician that I was prone to MRI panic. She replied as would any good dominatrix: “Listen, I don’t have time for that, just get in there and stay still!”

On this, my third MRI, I hit the panic button as soon as my head slid into the coffin. The American technician immediately slid me out. She spoke gentle nothings into my ear, put soothing if staticky music on the radio, pulled me out between sequences (I hit the panic button again), had me put on a pair of “magic glasses” (frames attached with a rear view mirror so that the small reasoning part of my brain would know that I was not being buried alive), pulled me out again (“you’re doing great, almost done”), and altogether mothered me through the ordeal in a way that is unimaginable in France.

I don’t think I’d have made it through the 20-minute MRI without the technician’s help, though I suppose that the Valium had something to do with it. The Valium also helped make the $425 bill more palatable, at least this time by credit card.

I did however get trapped in HIPAA hell when I called several days later to ask to have the films sent to my brother, a surgeon in California. The receptionist said she couldn’t because she was unable to identify me over the phone. It didn’t matter that I could recite my credit card number, my birth date, my social security number, my mother’s maiden name, and my pet’s name, nor that I could remember the color of the technicians sweet eyes and the earrings she’d been wearing.

Le Docteur

My insurance coverage in France allows me to be reimbursed for medical care in the U.S. for up to 30 days at a stretch, after which I’m expected to be well enough to return to France for further treatment. Were I to find myself on death’s doorstep in France, however, my policy asserts that I must be repatriated to the U.S., where I suppose I would languish on Medicaid.

France has universal health care, and despite its deficit and the countries notoriously high taxes, its health system actually seems to work. What is most surprising is that it works with little complaint from the public. Nurses are perennially dissatisfied with their pay and their working conditions while doctors (particularly divorced doctors) complain heartily about their taxes, but the public is generally well served without excessive waiting as in some countries with universal health care.

Soon after I returned to Paris I called my doctor here to make an appointment so as to go over my spinal issues and any others that he might discover during a check-up. As with many internist solo practitioners in Paris, my doctor doesn’t have a receptionist (or very high overhead), so he picked up the phone himself. He said that he was off the following morning but could make a trip to the office to meet me if necessary. I said it wasn’t urgent. He said, “Do you want to see me or not?”

One thing I like about my French doctor is that he’s always interested in trying to understand whether there may be a psychological component to an illness, which I find appealing because that way I get free therapy just for having an ear infection. I assured him that my degenerated disk was as real as had been the poison ivy (luckily he knew what PI was), though I admitted that some people would consider my distaste for being buried alive in an MRI as irrational.

But I hadn’t consulted him in 18 months and there were no other patients waiting, so we got into a lengthy wide-ranging discussion about aging, about exercise, about sex, about loved ones and death, about travels and home—for him, for me, and for the scientific community. After over an hour of talking, going over my results from the U.S., doing a simple physical check-up, and renewing the prescriptions I’d been given in the U.S., he concluded that I was a sound and healthy man with a bad back.

Then he charged me $30.

And at the door he kissed me on both cheeks.

My intent here is not to argue for a specific health system but to say that French-style universal health care is not the devil-in-scrubs that conservatives in American believe it to be. For American doctors a $30 consultation with a kiss must seem third-world yet they would undoubtedly agree that a doctor can have qualities (or not) no matter what system he works under. American lawyers, on the other hand, would find French health care shocking and despicable since the French systems of health and law leave little room for malpractice settlements that they would find sufficiently motivating. And they would regret the missed opportunity to sue for sexual harassment.

For now my sciatica has calmed down and the poison ivy is a lesson learned. I fear that one day, before long, I’ll have to submit myself to another MRI, but as I write this I’m fully back into the swing of things in Paris. I’ve nevertheless decided to postpone taking advantage of the series of salsa lessons that were a birthday present from a friend. And I’ve turned down the request from another friend to help in her suburban garden. I’m just going to stay right where I am and enjoy that other perversity of global warming: a warm seat in the sun in a Paris café in February.

© 2007, Gary Lee Kraut