This summer, hearing the moan of an elderly American as he suffered through the slow and sweaty flow through what for him was truly the Hell of Mirrors, I thought that it might help to offer a carrot, so I enthusiastically announced that we would soon be outside to see the fountain display.

“Fountains?” he said, “I’ve seen fountains!”

Hmm. So I tried a different tack and tried to impress him with the fact that the recent restoration of the Hall of Mirrors had cost $16 million.

“That’s not a lot,” he said. I soon learned that he had made his fortune in New York real estate, where you can’t even buy proper influence for that amount.

Power and prestige of another era, that’s what we expect to see at Versailles. Yet grand and historical as Versailles is, it doesn’t necessarily impress Americans or spark our imagination. And trying to impress my fellow Americans with numbers, I’ve found, is the wrong way to go. As much as we’re impressed with them at home they sound insignificant abroad.

If I mention 2000 rooms someone will invariably inform me that the Paris Hotel in Las Vegas has more than that, and an Eiffel Tower to boot, after which someone else will mention the 5600 rooms at the MGM Grand, and soon the entire travel party will be talking excitedly about high times in Vegas, until I remind them that that’s Las Vegas, this is Versailles. They’ll then look at each other in a sudden panic as though they’ve just boarded the wrong plane, followed by the sad realization that not only aren’t they about to be comped at an all-you-can-eat buffet but furthermore have to visit the gardens in the rain.

If I note that the king’s estate originally had about 20,000 acres (the domain is now one-tenth that), someone will invariably mention a ranch in Wyoming or a swath of Montana recently purchased by Steve Jobs or some such mogul, or a new island being created in Dubai or, as one traveler did, “Ma Daddy’s ranch in West Texas.”

Midwesterners are more likely to play along for a while with the idea that Versailles is impressive, only to bristle when offered numerical tidbits about, say, the 210,000 flowers currently planted each year or the 57 gardeners working here. “Well,” they’ll say, as though they have their honor to defend, “France is a socialist country, isn’t it?”

New Yorkers, I’ve found, will feign immutable nonchalance to any suggestion that they might be impressed by Versailles, not because they aren’t interested but because what they love about France is precisely that everything is so quaint and Old Europe, meaning unimpressive. And how can you impress Texans with the march from glory to guillotine when they’ve got oil wells in the back yard and 400 people on death row?

Of course, you needn’t be impressed with Versailles to find it worthwhile to visit. Nevertheless, the question then remains: What gives you the key to getting curious about Louisland? Is it the opulence of Louis XIV, the tinkering of Louis XV, the fall of Louis XVI? Is it their parties, their mistresses, their hygiene? Is it Marie-Antoinette, the gardens, the fountains?

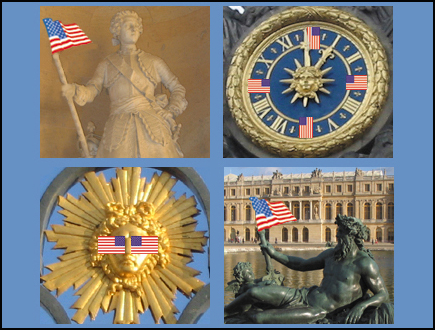

When all else fails, try this: Versailles, for all its reflection of historical French grandeur, authority, nobility, art, craftsmanship, and etiquette, is also a reflection of American power. Versailles may well be the French monument that most symbolizes American power, after the Statue of Liberty that is. So if you find it difficult to get curious about Versailles through its European history—believing that history to be little more than tales from an irrelevant, old, inbred continent—try getting curious about Versailles through our own.

A forewarning though: Approaching Versailles with American power and prestige in mind makes it more difficult to leave the royal estate with the common visitor’s comment “You can see why they had a revolution.”

Versailles Has Been Good to Us

Our history of mutual courtesy began with Louis XVI weighing in on the side of the American colonies in their fight for independence by covertly supporting the American cause for nearly two years before agreeing to official support with a treaty signed in Paris on Feb. 6, 1778. Six weeks later, the king officially receivedBenjamin Franklin in king’s bedchamber at Versailles, and two days later Franklin was presented to the royal family. On September 3, 1783, the signing of both the Treaty of Versailles between the French and the British and the Treaty of Paris between the British and the United States definitively ended the War for Independence. A street named Rue de l’Indépendance Américaine runs along the chateau’s southern wing.

On Oct. 6, 1789, an honorary American citizen escorted the royal family to house-arrest in Paris, never to return to Versailles. That was the Marquis de Lafayette, who, having made a name for himself on both sides of the Atlantic while fighting for the American cause, was made an honorary American citizen in 1787 by the states of Virginia, Maryland, and Massachusetts. Lafayette’s ambiguous position with respect to the monarchy was intertwined with his belief in American independence and democracy. In the summer of 1789 he penned an early draft of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, a fundamental document of the French Revolution (and beyond) that had been influenced by the U.S. Declaration of Independence. Thomas Jefferson, then American ambassador to France, assisted him in editing the declaration. It was ratified by Louis XVI, his arm twisted at Versailles on the night of Oct. 5-6, 1789, one of the most significant dates in the history of the chateau and of the monarchy. On that night Lafayette arrived at Versailles to protect the royal family from an angry mob. In the morning he ushered the family to house-arrest in Paris. The following year Lafayette sent Washington the key to the Bastille, still on display at Mount Vernon. In 2002 the U.S. Senate named him an honorary U.S. citizen.

Twentieth-century American power was consecrated here on June 28, 1919, when President Wilson negotiated and signed, along with Clemenceau for France, Lloyd George for Great Britain, and Orlando for Italy, the Treaty of Versailles officially ending the Great War. The location was chosen in part so for its symbolic value since it was here Prussian leaders had proclaimed a united, empowered Germany in 1871 and that French leaders sign a preliminary treaty ending the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 in defeat. Just as the signing of the 1783 Treaty of Versailles in the Hall of Mirrors had been intended to humiliate the British, the signing here of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles was intended to humiliate the Germans. In both cases, it was the Americans who were strengthened.

American Patronage

The beginning of crucial American patronage of Versailles began after WWI, with the astounding gift of 100 million francs (equivalent to over $100 million today) byJohn D. Rockefeller, Jr., in 1924, that helped repair extensive water damage, place new roofing on the chateau, and rehabilitate the Trianon Palaces and Marie-Antoinette’s Hamlet.

In 1961, as wars and treaties of decolonization weakened France’s role on the international stage, French President Charles de Gaulle exceptionally threw a state dinner in the Hall of Mirrors to honor the visit of President and Mrs. John F. Kennedy. The intention may have to been to show how magnanimous and compelling the French Republic could be, but this was no Louis XIV demonstration of strength. It was instead an unusually deep bow to an American president and his fine-legged Francophile wife.

Versailles has indeed been good to the United States. And Americans continue to be very good to Versailles.

After WWII, American donations continued with further funding from the Rockefeller family, Barbara Hutton, and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

More recently, several American or Franco-American associations have been particularly involved in helping fund the upkeep of Versailles. The Florence Gould Foundation, an American association dedicated to French-American amity, and the French Heritage Society, dedicated to helping preserve the architectural patrimony of France and the French legacy in America, have occasionally lent a charitable hand to Versailles since the early 1980s.

More specifically, the American Friends of Versailles was created a decade ago by Catherine Hamilton, in particular to collect $4.5 million to restore Louis XIV’sBosquet des Trois Fontaines (Grove of the Three Fountains) that already Louis XVI had allowed to full into decay. The restored fountains were unveiled at a high-society event in 2004.

In the past five years the let-them-wait-in-line curators of yesterday have given way to the keep-them-be-entertained directors of today, resulting into a policy shift in which corporate donors and sponsorship have increasingly been encourage and sought. Recent major corporate sponsorship includes the Vinci Group’s involvement in restoring the Hall of Mirrors and Breguet Watches’ contribution toward restoring the Petit Trianon and monuments in Marie-Antoinette’s garden. I wouldn’t be surprised if the French government hadn’t shamed those and other corporations into donating since until then the Americans were getting all the good press. And good thing too, because at the current exchange rate it’s rather expensive to restore a fountain.

Well, let them give. We can only benefit, for Versailles is in part ours, we who are part of that great culture enterprise known as The American Traveler Overseas.

© 2007 by Gary Lee Kraut

Also see Part I and Part II of this examination of Versailles on France Revisited.

Links

Chateau de Versailles: www.chateauversailles.fr. Open daily except Tuesday, 9am-6:30pm April-Oct., 9am-5:30pm Nov.-March.

Société des Amis de Versailles: www.amisdeversailles.com

American Friends of Versailles: www.americanfriendsofversailles.org

French Heritage Society: www.frenchheritagesociety.org