When does an American stop being a long-term resident of Paris and become an expatriate? The answer depends on both the subject and the onlooker, on whether one or the other sees expatriatism as a form of self-banishment/withdrawal, a statement of allegiance (residential, political, cultural, sentimental, etc.), or a natural transfer of adoption/affection/family.

All Americans living abroad are expatriates in the broadest sense of the word—living outside of the fatherland—but for Americans in Paris, and perhaps other European capitals as well, the term “expatriate” has over the past two decades lost its aura of (semi-)permanence and other-worldness. Travel is too effortless, communication too easy, families too extendable, and taxation too binding to find much use for a term describing the fact that one no longer resides in the U.S. Life abroad is a fluid state.

Franklin and Jefferson

Travel times used to make going abroad a much more momentous and long-term event, and visiting Paris then meant more than simply seeing the sights. It meant settling into life in Paris for a time. Benjamin Franklin, who lived here from 1776 to 1785 as colonial negotiator, American ambassador, and honorary member of the French Enlightenment, and Thomas Jefferson, who arrived in 1784 to replace Franklin and served as ambassador to France until 1789, were clearly diplomats rather than expatriates. Nevertheless, ever since they came courting France to assist in the American cause and bathed in the spicy mix of enlightened thinking and the good life à la française, Americans have been fascinated by Paris more than by any other foreign capital. Paris: the very name had an aura of sophistication and savoir-vivre where one lived surrounded by art, architecture, philosophy, and fashion, though before long revolution as well.

Late 19th Century

After the American Civil War, young artists—among them Thomas Eakins, John Singer Sargent, Mary Cassett, John McNeill Whistler—heeded the call of Paris as the center of academic arts, though young French artists were already a step or two ahead of them in the zigzag toward Modernism. By the 1880s Paris had become the undisputed capital of the art world. Along with its long-established suggestion of luxury and sophistication it also called to the mind artistic experimentation, sexual freedom, bohemian independence, and bourgeois well-being. In short, Paris had asserted itself a temptress for all walks of life.

The American Century

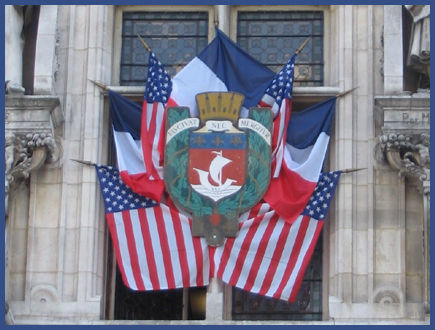

Yet it wasn’t until the end of World War I that Americans fully got into the act. British tourists had previously set the tone for travel to the City of Lights—the Right Bank triangle between the Louvre, the Garnier Opera, and Place de la Concorde bears their imprint. Now, our doughboys having been sent to the battlefields of France in 1917, “the American Century” had arrived. American soldiers discovered Paris after the war (simultaneously, Parisians discovered Americans of the heartland), and after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles of 1919 civilians began arriving in significant numbers and taking full advantage of the excitement of Paris during les Années Folles (the Roaring 20s) and of the dollar’s strength against the franc.

Artists and Heirs

Most were just visiting, but a sizeable expatriate community also developed. In many ways it was a two-pronged community as those who tended to stay for months or years were artists, writers and musicians on the one hand and representatives of American wealth, heirs of 19th century industry on the other. Some sought to integrate into local society, others stayed apart within the expatriate community, yet together they fully established an American love affair with Paris (and with the Riviera) that has been with us—and with the French—ever since.

The Murphys, Gerald (1888-1964) and Sara(1883-1975), were the archetype of wealthy American heirs in the playground of Paris and the Riviera in the 1920s and early 1930s. Gerald was heir to the Mark Cross luxury goods fortune while Sara and her sister Hoytie, another strong presence in expatriate circles in Paris, were heiresses to industrialist Frank Wiborg. Gerald briefly revealed his own talents as a painter once in Paris while Sara took to nurturing and financing American artists and writers (Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Dos Passos) and to befriending and becharming European artists, notably Picasso. The Murphys were major figures of expatriate life both as generous patrons of the arts and as leaders in the movement to Americans summering in Antibes on the Riviera (at their celebrated Villa America). Returning to the U.S. in the 1930s, they were influential in the development of artist colonies on Long Island, N.Y.

As to artists themselves, there is a danger for expatriates from any country of alienating themselves from the inherent genius of their homeland, but for American artists born around 1890-1900 Paris in the 1920s provided the stimulation, distance, and freedom from which they would reaffirm their very Americanness. Gertrude Stein, born in 1874, called this untethered youth “the lost generation,” and one of the consequences of being lost was that it allowed them to find themselves in Paris. Today their names are a roll call not only of those who experienced the excitement of expatriate life in the City of Lights while in their 20s and 30s, but of artists whose work would define American art and music at home and abroad: Josephine Baker, E. E. Cummings, Aaron Copland, F. Scott Fitzgerald, George Gershwin, Ernest Hemingway, Archibald MacLeish, Man Ray, Dorothy Parker, Cole Porter, John Dos Passos…

“If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast,” Hemingway wrote decades after having discovered the adventure of the city in 1918 at the age of 19. Though his romance with Europe continued through the 1930s and he made certain to be here in 1944 to take part in the liberation (of the bar at the Ritz), by 1928 he had discovered Key West, eventually calling that home.

In fact, many Americans who had called Paris home in the 1920s trickled away in the early 1930s, the result of natural burn-out and/or evaporating expense accounts due to the Depression. Others, such as Henry Miller, arrived, inspired by tales of the 20s. But it was the rare American whose life in France spanned the 20s and 30s, eventually leaving only, if at all, when the stench of European war got too strong, and rarer still those who returned after the war.

Those Americans whose lives in Paris span the two decades between the world wars and continually made their mark on the city were a distinctly female lot. They included a notable number of lesbians and bisexuals. Though their sexuality or other desires to break away from home unquestionably influenced their decision to live abroad, they are notable for their dedication to the wider aspects of life and times in 20s and 30s, defining, each in her own way, the life of the American expatriate in Paris.

Here are six of those women:

1. Josephine Baker (1906-1975). In 1925, Baker rode into Paris on the wave of jazz and African-American music that thrilled Paris nightlife through the 1920s—and that has made Paris a hot-spot for jazz to this day. She stood out in the Revue Nègre at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées then became a celebrity with her wild and sensual Banana Dance performed at the Folies-Bergère. In the 1930s she famously sang J’ai deux amours, mon pays et Paris (I’ve two loves, my country and Paris), yet having gained respect as an artist and as a black woman (she was in fact part American Indian) that she felt would have been unavailable to her back home, she largely abandoned her first love and settled in France for the long run. Baker took French nationality in 1937 when she married a Frenchman (her third of five husbands). She served in the French Red Cross and in the Resistance in Monaco during WWII and was subsequently awarded the Legion of Honor by Charles de Gaulle. Unable to have children, she founded a rainbow family after the war by adopting 12 children of diverse ethnicity. Honoring the centennial of her birth, a new swimming pool bearing her name was inaugurated in July 2006 in the Seine in front of the Mitterand National Library in the eastern edge of Paris.

2. Nathalie Barney (1876-1972). It’s a well known fact that money, sex drive, and a passion for the arts are the keys to good humor for expatriates in Paris. What’s less well known is that those may also be the keys to good health, to judge by the longevity of Nathalie Barney. Barney, originally from Ohio, settled into Paris in 1902 with a sizeable inherited fortune and quickly discovered the pleasures of living her homosexuality openly in the City of Lights. She made a name for herself as the host of a celebrated Friday evening literary-artistic salon that she held beginning in 1909 at her home at 20 rue Jacob. The salon’s heydays came in the 1920s and 1930s when it was a continual celebration of art, communication, community, freedom, and Lesbos-sur-Seine. After a break during WWII, when she and her lover Romaine Brooks, an American painter and sculptor, fled to Italy, where they were ideologically seduced by Mussolini, she continued to host the salon until in her early 90s. (Speaking of expatriate longevity, Olivia de Havilland, b. 1906, who recently honored in Hollywood in grande dame fashion on the eve of her 90th birthday, has spent most of the past 50 years in Paris.)

3. Sylvia Beach (1887-1962). Creator of the lending library and bookshop Shakespeare and Company at 12 rue de l’Odéon, Beach, with her companion Adrienne Monnier, formed a literary and business team that became central to the literary well-being of British and American travelers and expatriates. Born in Baltimore, she caught a first sweet whiff of expatriate pleasure when she was in her teens and her father was working as a Presbyterian pastor at the American Church, and Paris was clearly home by the time she turned 30. Closely linked through her efforts with Modernist writers after WWI, Barney is above all associated with James Joyce, whom she championed to the point of providing publication of his seminal novel Ulysses in 1920. The American Library in Paris (now located at 10 rue du Général Camou near the Eiffel Tower) opened in that same year.

4. Janet Flanner (1892-1978). Flanner, who hailed from Indianopolis, wrote the “Letter from Paris” for The New Yorker from 1925 to 1975 while living at the Hôtel Saint Germain des Prés, 36 rue Bonaparte. Flanner’s relationship with women, in particular with her life partner Solita Solano, natural groups her with the literary lesbians of the Left Bank, yet her reputation rests squarely on her work rather than on her love life. Her profiles of artists and politicians, her commentary on events and culture, and her visions of historical momentum in Europe allow her “letters” to span genres, combining the investigative and observational skills of a foreign correspondent, a travel writer, and a foreign witness. She withdrew to New York only during the German occupation and again in old age, leaving in 1975. Her collected “Letters from Paris” published as “Paris Journal, 1944-1965, received the 1966 National Book Award.

5. Winnaretta (Winnie) Singer, Princesse de Polignac (1865-1942). An heir to the Singer sewing machine fortune (her father, Isaac Singer, had at least 24 children from 5 different women), Winnie Singer, whose mother was French, spent much of her life in France and Italy. In 1893 she wed the Prince de Polignac, 30 years her elder, in a marriage of European aristocracy and American industry that flourished with mutual respect in which his boyfriends and her girlfriends mingled at their high society parties. The prince died in 1901, but between her money and his title she had all doors open to her in Paris. Singer was a devoted and knowledgeable patron of the arts of dance and music who drew many of the greats of her time to the artistic salon that she held until 1939.

6. Gertrude Stein (1874-1946). Stein’s standing—the good, the bad, and the misunderstood—as a major expatriate figure prior to WWII is due to her work as an experimental writer, her encouragement of young artists and writers, and her long-lasting “marriage” with Alice B. Toklas (1877-1967). An imposing figure of the literary and artistic expatriatehood of the Left Bank, Stein was an art collector, an experimental writer, and a genius-in-residence of her own artistic salon, where she enjoyed the intellectual challenge of younger male artists and writers (e.g. Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Pound). In 1907 she met Toklas who moved in with her three years later. Beyond “a rose is a rose is a rose,” Stein’s literary reputation rests mostly with her books The Making of Americans (1925) and, more accessibly, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933) She lived at 27 rue de Fleurus, just west of the Luxembourg Garden, from 1903-1938 before moving to 5 rue Christine, near the Seine. Stein and Toklas sat out the German occupation of France during WWII in relative comfort in the foot of the Alps east of Lyon, benefiting from the protection of Stein’s well-placed friends in the Vichy government. They are buried together at Père Lachaise Cemetery.

© 2006 by Gary Lee Kraut