The French electorate doesn’t necessarily vote according to its relative wealth, yet relative wealth is a pretty good indicator of voting strength, particularly in Paris and more dramatically in its surrounding region. There, generally speaking, flourishing professionals, and international business mark the west and southwest suburbs while working class, welfare recipients, and immigrants define the east and north suburbs. The result of this east-west wealth gap is clearly echoed in the ballot box.

In the presidential elections of May 2007, voters in the department (something like an American county) of Seine-Saint-Denis, which covers the suburbs just north and east of the capital, chose the socialist candidate over the conservative candidate 57% to 43%, while across the Seine in the departments of Haut de Seine and Yvelines, to the west of the capital, the percentage was nearly the exact reverse.

The extremity of the candidates’ scores in these respective departments clearly reflects the classenomic preoccupations of France, whereby the left demonizes financial success as something that can arise almost only from undue privilege and the right claims that the republic is imploding under the weight of the unmotivated workforce of the welfare state.

The east-west wealth divide of the suburbs isn’t a new phenomenon—far from it. It derives much of its original strength from the presence of royal towns to the west, in particular Saint-German-en-Laye and Versailles, along with other noble zones of the Ancien Régime. The map of the western suburbs of the deparment of Yvelines shines with the formal royal and/or imperial domains of Rambouillet (now official summer residence of the President of France), Marly-le-Roi (only the park remains), and Malmaison, along with a satellite of noble chateaux in or near the Chevreuse Valley: Chevreuse, Breteuil, Dampierre. And none of those names rhymes with socialism.

The financial split within what are now the city limits has also existed since the 18th century as nobility began developing in what are now the 7th and 8th arrondissements. Influenced in part by the regional divide, the capital’s wealth divide was accentuated with the transformation and expansion of Paris into a “modern” capital in the 1850s, which eliminated a number of lower class neighborhoods, forcing its population north and east, and the political divide immediately followed suit.

The parks, playgrounds, and breathing spaces to either side of the city—the woods of the Bois de Bolougne to the west and those of the Bois de Vincennes to the east—naturally also reflect the affordable leisure for their surrounding populations. The Bois de Boulogne is therefore marked by its polo grounds, race tracks, Bagatelle rose garden, and gastronomic and romantic restaurants, while the Bois de Vincennes is notable for its zoo, Floral Park, and cotton candy.

Paris, however, is a relatively and increasingly prosperous city overall, with few pockets of poverty. The more remarkable low-income zones are situated in the above-mentioned the northern and eastern suburbs of Seine-Saint-Denis. While the north-northeast/south-southwest wealth divide of the immediately suburbs shows no sign of letting up, gentrification of the eastern arrondissements of Paris is well underway.

Such gentrification began with the Marais in the late 1980s, and in the past decade the alternative bourgeoisie and youthful middle class has increasingly staked a claim to quarters further east, with some now coyly yet proudly spilling over into the near eastern suburbs. The financial split in Paris is therefore less dramatic but still quite notable.

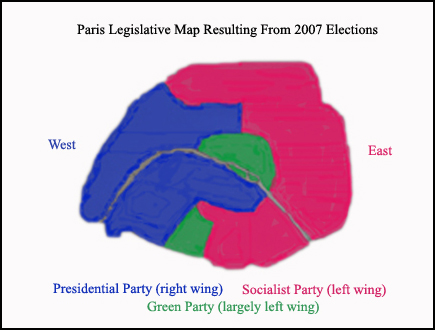

Nevertheless, despite this gradual gentrification, bigger money remains in the west, and the financial-political divide that marks the suburbs continues to mark the capital. In the legislative elections of June 2007 right-wing deputies were elected in the western arrondissements, which are historically defined by big business, the bourgeoisie, and the aristocracy, while left-wing deputies were elected in the northern and eastern arrondissements, traditionally defined by less privileged classes and immigration. Green candidates were elected in the central 1st circumscription and in the center-south 11th circumscription, certainly not for ecological reasons but simply because those Green candidate represented some kind of acceptable transition or hesitation between socialist and conservative leanings. (See illustration above.)

The traveler need look no further than the current political map of Paris and the surrounding region to know where to the luxury hotels, high-end restaurants, and upscale shopping are located.

Despite the optimistic creation of boutique hotels in the Marais and the opening of restaurants further out by some well-trained or adventuresome young chefs, the lion’s share of investment to draw well-to-do business and leisure travelers and locals remains the western arrondissements.

The star-studded restaurants and high luxury hotels (known in Paris as palaces) are already largely concentrated on the western half of Paris, from the first arrondissement and westward. And that’s precisely where two new palaces, Paris’s eighth and ninth, are under construction:

– In 2009 the luxury Asian chain Shangri-La will open a 118-room hotel in a late 19th-century mansion near Trocadero in the 16th arrondissement.

– In late 2010 the luxury chain Mandarin Oriental will open a 150-room hotel in an Art Deco building on rue Saint-Honoré in the 1st arrondissement.

The Marriott Group, meanwhile, is creating a new 118-room 4-star hotel (not a palace) to open in 2009 near the Arc de Triomphe in the 17th arrondissement.

Pity the traveler, however, who comes looking solely for the gloss and ideological comfort… but a little massage in the palace spa after a day on the touring trails won’t hurt.

© 2007 by Gary Lee Kraut