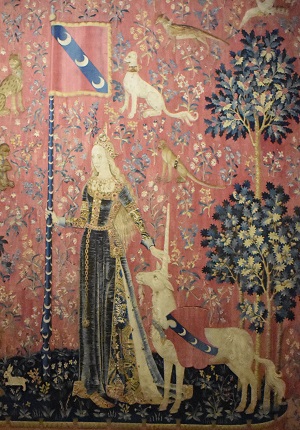

Detail of The Lady and the Unicorn, from the tapestry Sight, circa 1500. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée de Cluny – musée national du Moyen-Âge) – M. Urtado.

When it fully reopens at the end of 2020 upon completion of a 5-year restoration and reconfiguration project, the Cluny Museum will regain its place among Europe’s premier museums of medieval art and among Paris’s major museums. Already, the project is bearing fruit in the form of two concurrent exhibitions that explore some of the mysteries of medieval art and culture: Magical Unicorns (until Feb. 25, 2019) and Birth of Gothic Sculpture (until Jan. 21, 2019).

These exhibitions, along with a room presenting ivory, gold and enamel masterpieces from the permanent collection, display objects of beauty, intricacy and historical significance. Though their significance may initially be lost on the uninformed visitor, the visitor is quickly drawn in these exhibitions by the objects themselves and with the aid of explanatory panels are written in English as well as in French.

Magical Unicorns

While Birth of Gothic Sculpture is a scholarly exhibit, Magical Uniforms is easily accessible to the entire family. Who isn’t fascinated by the unicorn?—Not of the pink, star-eyed, Walmart kind but of the mysterious, fantastic, legendary kind that flourished in art and in emblems at the end of the Middle Ages.

The Cluny Museum’s most famous inhabitants are a lady and a unicorn, so it’s only natural that the first portion of the museum to be opened to the public during the restoration project is their habitat of six tapestries collectively known as the Lady and the Unicorn (La Dame à la licorne).

“Magical Unicorns,” the title of the little exhibition that precedes the six tapestries, may be redundant given the mysterious nature of this creature with the long spiraling horn. The unicorn has throughout history given rise to myths and fantasies, the exhibition presents various ways in which artists have represented this legendary creature in illuminated manuscripts, engraved works, sculptures and tapestries.

In some it is a magical animal whose horn could detect poisons and purify liquids. In others it symbolizes chastity and innocence. Several illuminated manuscripts evoke the traditional belief that unicorns could only be approached by virgin maidens. Yet other works represent the unicorn as powerful, aggressive or even malevolent. At the time, people were convinced of the creature’s existence; there were tales of travelers who claimed to have glimpsed the unicorn in the Orient. Unicorn fever spread throughout France in the late Middle Ages. Towns and powerful lords placed the unicorn within their emblems and coats of arms as a sign of their own magnificence. The Catholic Church took a liking to its symbol of purity and, when tamed by a young girl, of chastity, allowing the unicorn to appear in images with the Virgin Mary.

The holy of holies at the Cluny Museum, though, is the series of six tapestries known as The Lady and the Unicorn. The tapestries were woven around 1500, during the transitional period between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. There’s also a lion in each of the six, but the fabled unicorn is clearly the prosperous lady’s more intimate companion as she enjoys the five senses before setting aside her jewelry by her “own free will” (seul désir).

The Lady and the Unicorn had been all but forgotten when the six tapestries were rediscovered, in excellent condition, in the Château de Boussac in Creuse (central France) in 1841. The work’s beautiful feminine figures, the mystery surrounding its creation and the persistent presence of vegetation and familiar, wild or fantastical animals all captured the imagination. The myth of the existence of the unicorn had by then been debunked, but after 1882, when the Cluny Museum acquired the tapestries, the unicorn again became a source of inspiration.

In addition to presenting other examples of unicorns through the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, the exhibition shows how 19th- and 20th-century artists were inspired by these tapestries. A 5-minute video about the history of unicorns is shown alternatively in English and French.

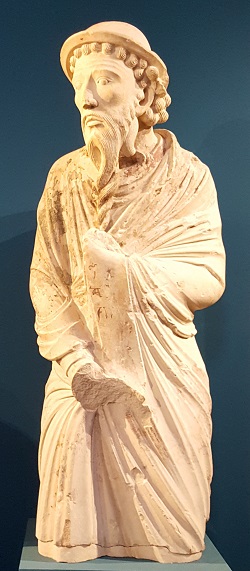

The Birth of Gothic Sculpture, 1135-1150: Saint Denis, Paris, Chartres

Europe has a number of first-rate museums devoted to medieval art, but the Cluny Museum holds a special place regarding works from 1000 to 1500 since the architects and artists of the territory of what is France today were on the forefront of developments during the Romanesque (about 1000 to 1150) and Gothic (about 1150 to 1500) periods of art and architecture.

Those round numbers are naturally illusory since there was actually no direct passing of the artful baton in 1150 from the subsequently-named Romanesque to Gothic, just as there was no midnight hand-off from Gothic to Renaissance in France at the turn of the 16th century. Each of those three broad cultural eras—Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance—produced its own strains, evolutions and geographical adaptations.

In this exhibition, which runs until Jan. 7, 2019, the Cluny Museum takes a close look at the transition between the Romanesque and Gothic sculpture as seen through the interplay of three centers of creation between 1135 and 1150: Paris, Saint Denis, eight miles to the north, and Chartres, 60 miles to the southwest.

In this exhibition, which runs until Jan. 7, 2019, the Cluny Museum takes a close look at the transition between the Romanesque and Gothic sculpture as seen through the interplay of three centers of creation between 1135 and 1150: Paris, Saint Denis, eight miles to the north, and Chartres, 60 miles to the southwest.

Enriched by the scientific contributions of the extensive restoration works conducted over recent years, starting with the western façade of Saint-Denis, the exhibition sheds new light on the earliest days of Gothic art and the explosion of its intricate carving.

No longer truly Romanesque, without yet being fully Gothic, the style that developed in Île-de-France (the Paris region and royal domain) and beyond between 1135 and 1150 has been puzzled together here as curators seek to present the wind of change and to follow the tracks of the notebooks of designs that circulated between construction sites.

Although Romanesque art continued to dominate in this period throughout most of Europe, in Île-de-France its supremacy was threatened during the 1140s. The construction sites of churches in Saint Denis, Paris and Chartres formed the cradle of a growing art that combined innovations as technical as they were stylistic and iconographic. Through emulation between builders, sculptors and sponsors, the first expression of Gothic sculpture was born and developed in the wake of a changing architectural style.

(The term Gothic itself wasn’t born until the 16th century as way for Italian architects to claim the superiority of their Renaissance creations over what they saw as barbarian, Goth-like works so at home in France. During much of their initial development, the arts and architecture of that era would mostly likely have be considered as simply French, since much—though certainly not all—of that development occurred within 100 miles of Paris, in every direction.)

Although we owe the invention of portals with column statues to sculptors working on the abbey church of Saint Denis, it was at Chartres cathedral that this model truly flourished, before adopting its most enduring expression, again at Saint-Denis, in the Valois portal. In the rivalry between these seats of power, the formation and propagation of new aesthetics played out in a complex intertwining of borrowings and departures. This new art found its origins in a quest for expressiveness which was achieved by the assertion of a style inspired by classical antiquity and marked by the art of the Meuse Valley around 1150. Bodies were given movement and came to life. They seemed to move.

Although we owe the invention of portals with column statues to sculptors working on the abbey church of Saint Denis, it was at Chartres cathedral that this model truly flourished, before adopting its most enduring expression, again at Saint-Denis, in the Valois portal. In the rivalry between these seats of power, the formation and propagation of new aesthetics played out in a complex intertwining of borrowings and departures. This new art found its origins in a quest for expressiveness which was achieved by the assertion of a style inspired by classical antiquity and marked by the art of the Meuse Valley around 1150. Bodies were given movement and came to life. They seemed to move.

The clear relationship between the engraved columns of the façade at Saint-Denis and a book known as “The Great Bible,” perhaps commissioned from Chartrian illuminators by Abbot Suger of Saint Denis, points in the direction of long-lost notebooks of designs. By bringing together sculptures, illuminations and stained glass panels, the exhibition shows their common sources of inspiration. More than just a simple juxtaposition of various repertoires, visitors will witness the birth of a hybrid art.

This is a scholarly exhibition that rewards an eye for detail. Adequate explanatory texts in English guide the visitor throughout, and audio- and visio-guides are available to further information.

The 130 works of art in the exhibition—column capitals, column statuary, etc.—come from reference collections of the Cluny Museum and the Louvre as well as various cathedrals, among them column statues from the Royal Portal of Chartres Cathedral. Several pieces are also on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.

Cluny Museum of the Middle Ages

28 rue du Sommerard, 5th arr., Paris.

Open daily except Tuesday 9AM-5:45PM. Closed Jan. 1, May 1, Dec. 25.

Metro Cluny-La-Sorbonne or Saint-Michel or Odéon.

Entrance: €9, includes entrance to the exhibitions.

The museum’s main portion, the late-medieval mansion of the Abbots of Cluny, is closed for renovation until late 2020. During that time, various exhibitions will be held in the frigidarium or cold pool, a remnant of the ancient Roman bath complex that stood on this site, while the Lady and the Unicorn and a selection of treasures from the permanent collection will also remain on display. Entrance outside of exhibition periods is 5€.

Eagerly awaiting the completion of renovations at both the Cluny AND the Carnavalet!