Saint Eustache Church © GLKraut

I’ve been going to church a lot lately—for the art, the architecture, the history, the decorative flourishes, the organs, to get out of the rain, to hang out, what with museums and cafés closed during this phase of the pandemic. I’ll call a friend and say, “Hey, want to meet at church?,” though neither of us is Catholic.

We take our hats off when we go in. It’s the respectful thing to do. We respect the sign that says to remove our hats, while the clergy and worshippers respect that we’re not there for worship. Just looking. Mutual respect, of necessity and by law, since most the most notable churches of Paris—those most worth visiting for their art, architecture, organs, etc.—don’t belong to the Church, they belong to the city, to Parisians. They’re our churches. No religious litmus test is required of the visitor. Praise the secular Republic!

The fact that many churches in France don’t belong to the denomination that holds services in them may sound like an aberration, but public they are.

A bit of history will clarify before the video tour at the end of this article.

Blasphemy, Equal Rights and Vandalism

Prior to the French Revolution, under the ancien régime, the vast majority of French were Catholic by virtue of baptism—less so by faith, as the Revolution would show. Religious nationalism, as we would call it today, would not be part of the social order of the new republic. Neither would blasphemy be a crime; it was decriminalized in 1791—not just regarding the prophets, saints and objects that Catholics hold sacred, but for what Protestants and Jews revere as well, since 1791 was also the year that they were given full and equal rights of citizenship. What they held sacred could be blasphemed or ignored as well. (There weren’t many Muslims in France to speak of at the time, so the Revolution wasn’t concerned with Islam per se.)

Freed of the domination of Catholicism, some also felt free to desecrate religious art, architecture and burial sites that were reminders of pre-Revolutionary repression. The term “vandalism” was coined in 1794 to describe willful destruction worthy of the Vandals, but the government soon put a stop to that, for it wasn’t Church property that was being damaged but public property. Indeed, property once considered to belong to the Church or to nobility now belonged to the State. Hadn’t it all been created on the backs of the people?

But what to do with all that property? How to allow the Church to function on public property? How to pay for its maintenance? After the revolutionary decade, the Napoleonic era went a long way in sorting that out with a heavy hand, but throughout the 19th century there were doubts, conflicts and upheavals with respect to the separation of Church and State, even while new churches and now temples and synagogues were being built. Sacrilege–sacrilège!—even became a punishable offense for a time, though no longer, hallelujah. Of course, it’s one thing to disrespect a worshipper’s divine mysteries or Biblical bluster, while another to slander the worshipper or incite hate.

It’s a complicated story, as it is everywhere, but if there’s one chapter that’s particular to France and of which all visitors should be aware, it’s the one entitled “The Law of December 9, 1905 Concerning the Separation of Churches and the State”—the Law of 1905, for short.

The Law of 1905 Concerning the Separation of Churches and the State

The Law of 1905 establishes the principles of secularism (laïcité), guarantees freedom of worship, and defines (along with subsequent texts) the ownership and use of previously built religious edifices and their contents. Here’s the actual law in French. Here’s a good overview in English, including the historical context.

Generally speaking, as a result of the law and the Vatican’s response to it, municipalities own churches, parish chapels and presbyteries built prior to 1905 along with most of the furnishing, decorative elements and artworks existing at the time. State-sponsored temples and synagogues, too, fall under the law, though there were far fewer of them at the time. The State, meanwhile, has ownership and responsibility for cathedrals (at least those originally built as cathedrals prior to the Revolution, since some have changed roles and others have since been built) and chapels on state-owned property. Notre-Dame, the cathedral of Paris, is therefore owned by the State.

(The Orthodox church was scarcely present in Paris in 1905. And other than a small building that went up in the 1850s for Muslim funeral services in the city-run Père Lachaise Cemetery, there was no purposely built mosque in Paris until the construction in the 1920s of the Great Mosque of Paris.)

Not Eternal Damnation but Endless Restoration

France has 42,258 parish churches and chapels, of which only 1951 belong the dioceses, according to a 2016 inventory of the nation’s Conference of Bishops. The City of Paris owns a whopping 96 religious buildings: 85 churches, 9 Protestant temples, and two synagogues. Among these, 68 are officially designated as Historical Monuments and benefit from certain protections and measures of preservation as such. The Catholic Church or a Protestant or Jewish association has been granted use but does not own those places of worship.

While “The Republic neither recognizes, nor pays salaries for, nor subsidizes any form of worship” (Article 2 of the Law of 1905), the maintenance and restoration of State- and city-owned property falls upon its owner. Contrary to when many of these religious edifices were built, no one dare argue that tax money will help save souls and steer sheep to heaven. Lofty enough is the ambition of ensuring that the roof doesn’t leak and that fine works of art don’t fall apart. The Law of 1905 didn’t send France to eternal damnation, but it did set the nation on the path to endless restoration.

Instead of looking to heaven for answer, we look to the budget. As you can imagine, a sizable budget is required to maintain and restore the 96 city-owned religious edifices, 40,000 works of art, 130 organs, acres of stained glass and decorative painting and much liturgical furnishing. The City of Paris earmarks 10-15€ million (about $12-18 million) per year for these projects. (The City of Paris did not return repeated requests for the specific figure in the current budget.) Contributions from the state (through the Ministry of Culture), foundations (this, for example), corporate sponsors and private donors add a few million to the budget each year, assigned to specific project, from structural work to the restoration of a chapel or a work of art.

As examples of major maintenance and restoration projects: The recently completed restoration of the interior of Saint-Germain-des-Prés cost 6.4 million euros. Cleaning and repairing the southern façade of Saint Eustache at Les Halles cost 2.3 million, with a large wish-list yet to go inside. The Trinity Church in the 9th arrondissement is now in the midst of a 26-million-euro facelift. The city has earmarked 6.6 million for work on the belltower and northern transept of Saint Gervais, behind City Hall. Etcetera, etcetera.

As noted above, Notre-Dame belongs to the State so restoration efforts there are typically minimal on the Paris budget. However, the cathedral was still smoldering from the fire of April 15, 2019 when the mayor of Paris pledged a public contribution of 50 million euros on behalf of Parisians. (Overall pledges, public and private, eventually approached one billion.)

Guide to Church Visits

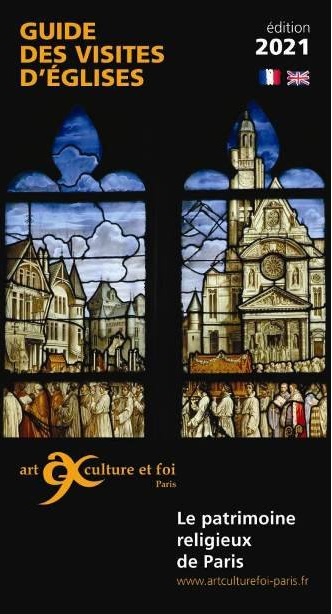

Paris isn’t Rome, of course. The City of Light has neither the breath nor depth nor intricacy of the ecclesiastic (dis)order of the Eternal City. Nevertheless, to take measure of the churchscape of Paris, residents and visitors can pick up a booklet entitled Guide des Visites d’Eglises (Guide to Church Visits). Available free in many churches and at the Paris Tourist Office, it indicates 112 churches and places of worship and provides brief descriptions—in French and in English—of their history and architectural and artistic points of interest. The booklet is published by the Catholic organization Art Culture et Foi / Paris (foi means faith, not to be confused with foie, meaning liver, as in foie gras).

Paris isn’t Rome, of course. The City of Light has neither the breath nor depth nor intricacy of the ecclesiastic (dis)order of the Eternal City. Nevertheless, to take measure of the churchscape of Paris, residents and visitors can pick up a booklet entitled Guide des Visites d’Eglises (Guide to Church Visits). Available free in many churches and at the Paris Tourist Office, it indicates 112 churches and places of worship and provides brief descriptions—in French and in English—of their history and architectural and artistic points of interest. The booklet is published by the Catholic organization Art Culture et Foi / Paris (foi means faith, not to be confused with foie, meaning liver, as in foie gras).

Created in 1989, the organization’s mission is to undertake, encourage and support cultural and artistic activities in the diocese of Paris. The booklet therefore only concerns Christian places of worship. In addition to Catholic churches, it lists some Protestant temples and Orthodox churches, the more historic of which were built as Catholic churches then later designated by the State or the city for use by the other Christian denominations.

The city-owned synagogues naturally have no place in the booklet. For information about visiting the Great Synagogue, la Grande Synagogue de Paris, see here. For information on visiting the Great Mosque, la Grande Mosquée de Paris, see here.

Not all those listed in the booklet are property of the City of Paris since it also includes churches and chapels built after 1905. Most are open daily while others can be visited on a regular bases, though they may have special requirements for security reasons. (Smaller churches may consider walking around during mass as an intrusion, though you’re generally able to stand in the back if you don’t feel like taking a seat.) Not all are worth the detour. However, all offer free guided tours (whether rarely, occasionally or often), conducted by volunteers, parishioners or members of Art Culture et Foi / Paris. Times and dates are indicated. Thirty-eight of the listings have QR codes, which are also posted in the churches, for further information on your smartphone. (The few Paris churches and chapels worth visiting but not found the booklet are absent because they don’t offer guided tours, such as Sacré Coeur.)

With or without further information, curiosity is rewarded. If a church door is open, why not remove your hat and walk in? I do. As I say, I’ve been going to church a lot lately. Here are some that I’ve visited:

Video: Gary Goes to Church

© 2021, Gary Lee Kraut