History has never been America’s strong point, and our grasp of our own role in the First World War is no exception. We need more context and basic information than other combatants of the Great War in order to begin to understand its significance. Thanks to the new little museum at the foot of the American Monument above Chateau-Thierry, context and information are now readily available on a daytrip or more from Paris.

* * *

Americans visiting the D-Day Landing Zone of Normandy quickly learn the invasion map by heart: the five thick arrows pointing toward Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword Beaches; the lines indicating the flight plan that dropped paratroopers and released gliders to the east and west of the zone; the grey band representing the joining of Allied forces throughout the zone and their push inland; the black arrow of the German counteroffensive around Falaise, and finally the victorious block of Allied grey up to the Seine River. Mission accomplished.

The movement on the ground was full of pitfalls, of course, but between the channel, the river and the sweeping color-coded movement of troops, the momentum of the Invasion of Normandy appears clear, even inevitable, whether your recognize the names of individual towns and villages or not.

A map of First World War battle zones is not as easy for American’s to grasp. Yet the vast majority of the American Expeditionary Force joined our Allies along the Western Front in France, with some in Belgium.

Brits may be more comfortable with the map of the Western Front of WWI because of proximity, because the Somme, Amiens, Ypres (Belgium) and the Marne still resonate with many, and because the Imperial War Museum in London continues to draw crowds. Many Canadians can situate Vimy Ridge because it speaks so clearly of the coming of age of a nation and because the monument there is the most stunning Allied war memorial in all of France. Australians know of Villers-Bretonneux.

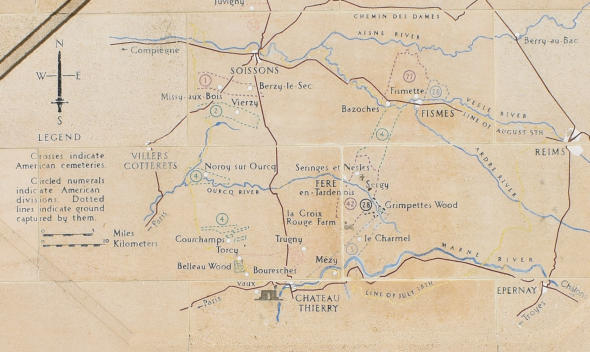

But the map below of the Aisne-Marne Salient showing ground captured by American divisions after July 18, 1918, an essential element in the development not only of the war but of “the American Century,” speaks little to us…

… even though it’s shown on the most impressive American war monument in France, the American Monument on Hill/Côte 204 above Chateau-Thierry, 60 miles northeast of Paris.

History has never been America’s strongpoint, and our grasp of our own role in the First World War is no exception to that. We need more context and basic information than other participants of the Great War in order to begin to understand its significance. Thanks to the new little museum at the foot of the American Monument, context and information are now readily available on a daytrip or more from Paris.

The museum

The museum, like the monument above it, is the work of the American Battle Monuments Commission. A presentation space was created along with the monument in the late 1920s but it wasn’t furnished until now, as part of the overall restoration of the monument.

The museum, like the monument above it, is the work of the American Battle Monuments Commission. A presentation space was created along with the monument in the late 1920s but it wasn’t furnished until now, as part of the overall restoration of the monument.

As it had at the Normandy American Cemetery on the eve of the 60th anniversary of D-Day in 2004 with respect to the Second World War and the Battle of Normandy, the ABMC saw the need provide American visitors with an overview of the American intervention in the First and battles in the Aisne region of France on the 100th anniversary of our participation in major combat during that war. After all, pristine cemeteries and imposing monuments and pristine cemeteries aren’t intended merely to serve as dramatic backdrops for the occasional speech by a government official but are to be visited, honored, understood, questioned and contemplated year-round.

Despite its modest size, or rather because of it, the new museum plays its role to greater effect than the museum in Normandy. Whereas the ABMC’s Normandy museum seeks to direct and frame the visitor’s emotions, the Chateau-Thierry museum appears to have no agenda other than to provide visitors with context and an introduction, where much is needed, to the Great War and to American involvement in it.

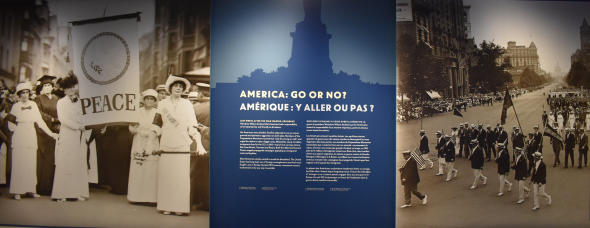

The information is brief, just enough to get the uninformed visitor curious. This is not a roll call of the dead but of the situations and events of our involvement in the war: the German attack on Belgium and France, trench warfare, American isolationism, American interventionism, “Lafayette, we are here!,” the arrival of green American troops in 1917, Pershing’s plan, an American army under American command, the German offensive of 1918, American entrance into action in around Chateau-Thierry, the Battle of Belleau Wood nearby, “The Rock of the Marne,” photographs and posters, the Armistice, the death toll, and the creation of the ABMC, of cemeteries and monuments.

The presentation can be visited in 30 minutes. This isn’t where one studies the war, rather where one finds the spark to understand an essential period in American history and in our relationship with the world as a global power… and to begin to understand the significance of the monument and of the map shown on it.

The presentation ends by giving credit to Paul Cret (1876-1945), the French-American architect (and veteran) who designed or oversaw the design of many WWI monuments and memorials in France, including full involvement in the American Monument here and the chapel at the Aisne-Marne Cemetery five miles away. The shout-out to Cret is well deserved. Though his name isn’t known beyond architectural circle, Cret’s work is familiar to many: the Rodin Museum and layout of the Ben Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia, the Indianapolis Central Library, the Cincinnati Union Station, the Detroit Institute of Art, the main building and campus layout of the University of Texas at Austin, the headquarters of the Federal Reserve in Washington, D.C., and others.

The monument

The American Monument fulfills the four major characteristics that the AMBC sought in the 1920s to honor the American presence in the war: it’s built on the site of a significant battle; it’s visible from afar; it has a commanding view of a zone covered by American military operations, and it is accessible to the public.

(In addition to the American Monument at Chateau-Thierry, the two other major WWI monuments in France also fulfill these criteria: the Montsec Monument nine miles from the Saint Mihiel American Cemetery, and the Montfaucon Monument several miles from the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery. Both monuments are further east, in the Meuse region.)

The view from the monument shows what a strategic position this was, on a hill known as Côte 204 according to its wartime designation, overlooking the Marne River and the flat land beyond it that. We are near the southern end of the reach of Germany’s Spring Offensive of 1918, which is as close as their troops would come to Paris during the war.

In 1914 the First Battle of the Marne had seen British and French troops stop the German momentum that had swept relentlessly through Belgium and deep into northern and northeastern France. Now, in 1918, the Americans, first under French command and soon under their own, joined the fray in legendary fighting including the Third Battle of the Aisne (May 27-June 6), the Battle of Belleau Wood (June 6-26, 1918) and the Second Battle of the Marne (July 15-Aug. 6), where the 3rd Infantry Division would earn its nickname “The Rock of the Marne.” Those and other battles along the Western Front would set in motion a complete shift in momentum that would overwhelm German forces several months later.

Having enter along a long driveway, the visitor arrives before a rigid colonnade in a tight, unyielding formation. Against this backdrop of a classical theater of sorts, female allegorical figures of France and of the United States stand center stage. They hold hands as though standing severely united before a tomb in impassive echo of the colonnade itself. The figures are the work Alfred-Alphonse Bottiau, a French sculptor who worked with Cret on a number of ABMC monuments.

Division numbers, insignias and names of battles in the region are inscribed on the monument. They may not be as evocative as Omaha, Utah, Gold, Juno, Sword, but perhaps your curiosity will be awakened to learn more about the origin or evolution of U.S. divisions, their insignias and engagements. Among them:

– the 1st “Big Red One” Division whose 2nd Battalion, 16th Regiment became the face of Americans in France when it paraded through Paris to Lafayette’s grave on July 4, 1917;

– the 2nd “Indianhead” Division, whose insignia of an Indian in profile with headdress was derived from an emblem a driver had painted on his truck;

– the 26th “Yankee” Division, drawn from units from New England;

– the 28th “Keystone” Division formed from units of the Pennsylvania National Guard;

– the 32nd “Red Arrow Division” from the Wisconsin and Michigan National Guards;

– the 42nd “Rainbow” Division drawn from units that stretched “like a rainbow” across 26 states and the District of Columbia;

– the 77th “Statue of Liberty” Division from New York City,

– and the 93rd “Blue Helmet” Division, among others. The 93rd was an African-American segregated division whose regiments (269th Harlem Hellfighters of New York, the 270th Black Devils of Illinois, the 372nd Infantry Regiment) were welcomed as fighting forces by French commanders (who issued them blue French helmets) at a time when American commanders saw African-Americans as a labor-only force.

After a visit to the museum, the map of American military operations below the eagle on the eastern side of the monument may still be hard to grasp, but it will be coming into focus as you head next to Belleau Wood and the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery.

Practical tips for visiting the area

A day of WWI touring in the immediate area of Chateau-Thierry can include the American Monument, Belleau Wood and the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery over the course of several hours. It’s then possible to pursue the theme of WWI sights with a visit to the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery, 17 miles northeast of the Aisne-Marne, and the Quentin Roosevelt Fountain and crash site several miles further east.

Or, after visiting the sights around Chateau-Thierry, visitors can shift their attention to wine by visiting Marne Valley champagne producers in the area.

The Curious Tasting & Travel Club organizes occasional private and semi-private tours of the Chateau-Thierry area for a morning of war touring followed by an afternoon of champagne winery touring.

See Chateau-Thierry area’s official tourist site for information about sights, activities and commemorative events in the area. The tourist office occupies the ground floor of the France-America Friendship House.

© 2018, Gary Lee Kraut