Janet Hulstrand tells about her encounter with Holocaust survivor Paul Niedermann and interviews him about his life, his work and his childhood.

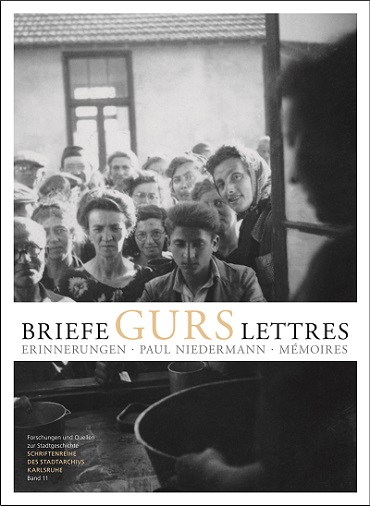

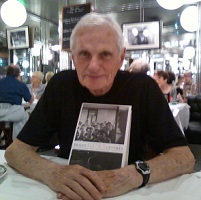

(Image above: Detail of the cover of Paul Niedermann’s memoirs.)

* * *

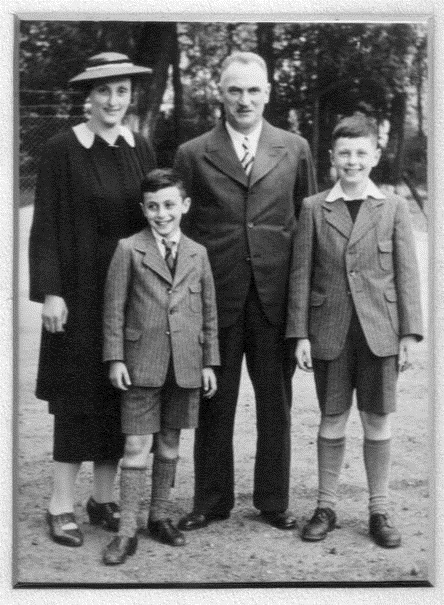

The south of France is not generally associated with the Holocaust. But for many of the more than 6,500 Jews deported from the German provinces of Baden-Wurttemberg and the Palatinate during a single night in October 1940, the journey to Auschwitz passed that way. Among those rounded up was the family of Paul Niedermann, a boy of twelve at time, who would later become my friend.

I had first met Paul in 1978 when I was living in Bry-sur-Marne, where he had a small photo business. We became good friends, but I never knew that he was a Holocaust survivor until 1987, when he was called upon to provide testimony at Klaus Barbie’s trial for crimes against humanity. Prior to that, he never spoke of it: I didn’t even know that he was Jewish. The closest he ever came to revealing anything about what he had lived through before that was one day in the course of a conversation we had, when he mentioned that he had had “a difficult childhood.” At the time I didn’t know what he meant by that, and I didn’t press him for details.

What happened is this: during the night of October 22-23, 1940, Paul and his family were removed from their home and taken to the train station in Karlsruhe, where they and hundreds of other Jewish citizens were held for 24 hours. Then they were loaded onto trains and sent to an internment camp at Gurs, near Pau in the south of France. At the time this was in the unoccupied part of France, under the control of the Vichy Government.

In March of the following year, Paul and his family were transferred from Gurs to another internment camp, at Rivesaltes, near Perpignan. From there his parents were sent to Auschwitz, where they both perished.

Before his parents were sent to Auschwitz, Paul and his younger brother Arnold had been rescued from Rivesaltes by Vivette Hermann (later known as Vivette Samuel), who was working with an organization called OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants) to save the lives of Jewish children. A Quaker group had worked out an arrangement with the U.S. government for the United States to accept five convoys of refugee children. Through this arrangement Arnold was given the chance to go the U.S., where their mother’s sister lived: however, the Quakers were unable to send Paul since, under the terms of the agreement, only children under the age of 12 could be admitted. Thus Paul, at 14, was given the responsibility, as “head of the family,” to decide whether Arnold should go to the U.S., or stay with him in France. “I didn’t think about it too long. I gave my consent,” he says. His parents were gone, he knew not where. And it would be 14 years before he would see his brother again.

For the next couple of years Paul lived as a fugitive, hiding and being hidden in a series of safe places in France and Switzerland, including the children’s home in Isieu that was raided by the Gestapo on April 6, 1944, shortly after he had left there. Of the 44 Jewish children and seven adult caregivers who were arrested, only one survived deportation. Most were killed at Auschwitz.

After the war Paul made his life in France, but took frequent trips to the United States to spend time with his brother in California, and his aunt.

In 1992 Paul learned that his brother was in possession of a box of letters that his mother had written from Gurs and Rivesaltes to her sister in Baltimore. Arnold could not bear to read them, and for many years Paul couldn’t either. Arnold passed away in 2000. Paul eventually decided that he would allow these letters to become part of the public record of the Holocaust. Beginning in 2007 he read them all and translated them into French. They were published in a bilingual (German/French) hardcover edition, Briefe einer badisch-jüdischen Familie aus französischen Internierungslagern / Lettres d’une famille juive du Pays de Bade internée dans les camps en France (Info Verlag, 2011; separate German and French editions have also been published).

One of the most impressive things about Paul is that despite all he went through he has never succumbed to bitterness. Another is his level of energy: since 1987, he has spent most of his time traveling and witnessing to school, church, and other groups in France and in Germany. He has also appeared in several documentaries, and a recording of his oral history is in the collection of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. He takes very seriously the responsibility of telling his story, a responsibility that he feels more acutely as the number of Holocaust survivors still living dwindles.

What follows are his answers to my questions, which I have translated from the original French.

Janet Hulstrand: You lost your parents at an early age, and in a particularly terrible way. But what are some of the happy memories you have of your parents and grandparents, and of Karlsruhe before it was taken over by the Nazis?

Paul Neidermann: Certainly a childhood and adolescence in Nazi Germany was not easy for a Jewish child, but we were a very close family. Inside the shelter of our home, my childhood always seemed normal to me.

My family was observant, and we didn’t have any problems in this regard. Before the Nazis came into power, we were very well integrated into the city, and we had both Jewish and non-Jewish friends. I started school in 1933, and I was the only Jewish child in my class. The city of Karlsruhe, which was relatively young, had never had a ghetto, so Jews lived all over the city.

J.H.: You celebrated your bar mitzvah in the internment camp at Gurs. How did you manage to do that, and what was it like?

P.N.: I spent the first two weeks at Gurs in “Block K,” the women’s barracks, because my mother, being a good Jewish mother, didn’t want to let my little brother and me out of her sight. But when I turned 13 I was considered an adult and was transferred to Block E, where my father was.

Back in Germany I had been preparing for my bar mitzvah. A rabbi had saved a scroll of the Torah, and that is how the ceremony took place in Block E, with my father and grandfather, along with many other people I didn’t know—including the rabbi. There certainly was no special meal, and there were no gifts! At the time I didn’t think much about it—our concern at the time was first and foremost to survive.

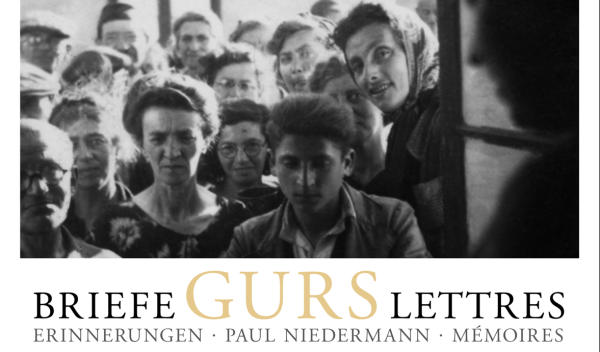

J.H.: Can you tell the story of how you came to have the picture of your mother that is on the front cover of your book?

P.N.: We were transferred from Gurs to a camp at Rivesaltes, and it was in that camp that I stole the photo of my mother. The director of the barracks had sent me to deliver the roll call list to the director of the camp. When I was there, I saw a big box full of photos near the door. My family was always interested in photography, so I was curious about the pictures. I impulsively grabbed a handful of photos without looking at them. Back in my barracks I looked to see what I had gotten, and I saw that my mother was in one of the photos I had taken, there in the front row, waiting for soup to be distributed. Two weeks later, she went to Auschwitz, where she was killed. This photo is certainly the most precious of all the treasures I’ve been able to save from oblivion.

J.H.: I knew you for a long time before I ever knew about your experiences as a child during the war. What made you decide to begin sharing these life experiences with others?

P.N.: For a long time I wasn’t able to talk about what I had gone through. I had a real block about it. But I was called as a witness in the Klaus Barbie trial in 1987. [Ed note: Barbie was the notorious head of the Gestapo in Lyons. It was because Paul had been a resident at the safe house in Izieu that he was called as a witness for the prosecution in Barbie’s trial.]

The prosecutor, Pierre Truche, a wonderful jurist, questioned me about the smallest details without emotion. For him, I was just another witness. But for me he was kind of a “shrink,” without his knowing it. At the trial there were thousands of people who heard my story. Afterward many invited me to speak, mainly in schools. I’ve continued to go over all of what happened in my head now, and that’s how I became the witness of my own story, which is of course a part of the larger History of the Holocaust.

J.H.: How do you feel about the generation of Germans who allowed the rise of Nazism to take hold?

P.N.: During the war, everything German was the Enemy. But afterward, I realized that hate is a completely sterile emotion, and that you can’t build anything on this foundation. The criminals of that time are all dead now, and I have no quarrel with those who were born afterward. That allows me to speak to young Germans and also Frenchmen and women, to bear witness to what was possible and still is, unfortunately. I tell young people today that they must be involved in such a way that these things can never happen again!

J.H.: Many people who suffered as much from hatred as you and your family did come away from the experience embittered. While it is easy to understand how this can happen, and I believe it is wrong to blame victims of hatred who do end up this way, you have taken a different path. How did you come up with the courage, strength and compassion to retain your essential human kindness and compassion, and your positive attitude about life?

P.N.: More than anything, I believe that I owe my optimism and especially my positive attitude to my parents, who made me who I am. I thank them for this every day.

J.H.: You have received many awards and accolades for your work as a witness to the Holocaust. Can you tell us about some of them? Is there one of them that is particularly meaningful to you?

P.N.: My work as a witness has been widely recognized. I might mention the Federal Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. I’ve also been given the opportunity to tell my story in both Protestant and Catholic churches: all these are signs of respect for the Jewish communities in France and Germany. But I am especially proud of an abundant correspondence I have had with German and French youth, who have proved to me that I’m not “preaching in the desert.” I am very happy to be able to continue this important work, even at 86 years of age. Somebody has to do the job!

© 2014

Acknowledgement by Janet Hulstrand: Because of his dedicated efforts as a witness, Paul’s story has been given fairly broad exposure in France and in Germany. When I asked if he would be willing to share his story with an English-speaking audience, he readily accepted. I am grateful for the time and thought he put into answering my questions. I am also grateful to Gary Lee Kraut for the opportunity to bring Paul’s story and outlook to an American audience.

Janet Hulstrand is a writer, editor and teacher of writing and literature based in Silver Spring, Maryland. She teaches Paris: A Literary Adventure each summer in Paris for the Education Abroad program at Queens College, CUNY, and literature classes at Politics & Prose bookstore in Washington, D.C. She writes the blog Writing from the Heart, Reading for the Road. She has also profiled the American poet James A. Emanuel for France Revisited in two articles found here and here.

For another France Revisited article about deportations and the Shoah see Jewish Paris: The Deportation Memorial, the Shoah Memorial and the Holocaust Center.