By Sarah Towle

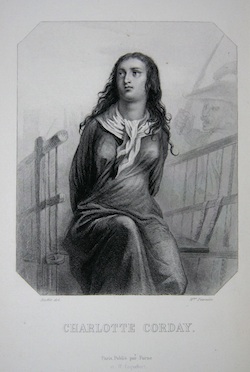

On 13 July 1793, the eve of the fourth anniversary of the sacking of the Bastille, 24-year-old noblewoman, Charlotte Corday, knocked on Jean-Paul Marat’s door for the third and final time. She’d already been turned away twice that day by Marat’s companion, Simone. But this time Charlotte arrived bearing a letter, penned in her own hand. The letter stated that she had come to name names; that she was prepared to betray to Marat the 18 Girondin “enemies of the Revolution” that he sought.

Simone took the letter and shut the door with a slam, leaving Charlotte alone on the drab landing outside Marat’s Left Bank home, located just around the corner from his press.

It was Charlotte’s last chance to retreat, but she did not. She’d written her farewell letters. She’d paid off her debts. She’d endured the long coach journey to Paris from Normandy.

Charlotte had looked for Marat at the Palais Royal, considered the birthplace of the French Revolution as people could talk freely there, without fear of censorship. The home of the king’s cousin, Louis-Philippe Joseph II, duc d’Orleans, it was therefore royal property and the king’s police were forbidden to enter. Presses were even set up there to print broadsheets and journals espousing enlightenment values. And folks gathered night and day to share revolutionary ideas, out loud! Louis-Philippe Joseph, encouraging it all to happen, changed his name to Philippe Egalité.

She’d pursued Marat at the National Convention as well, only to learn that he would not likely ever be found there again. He was ill, perhaps dying of an incurable skin disease contracted while hiding from enemies in the Paris sewers. His only solace was soaking in a bath of medicinal herbs. When the pain was very great, he remained in his bath all day.

She’d come this far. Now a mere threshold stood in the way of her greater goal. She stood her ground and waited.

The letter did trick. Marat granted Mademoiselle Corday entry into a small, square room with a brick-tiled floor. A map of France hung upon worn wallpaper. There, she found Marat languishing in a tub the shape of a sabot, an old wooden shoe. A board lying across it served as a writing table. To keep warm, Marat sat upon a linen sheet, the dry ends covering his bare shoulders. A second sheet, draped across the tub and writing table, offered him a bit of privacy from his visitors.

Marat was strange and unpleasant, thin and feverish. His head was wrapped in a filthy, vinegar-soaked handkerchief. Open lesions on his skin reeked of decaying, rotten flesh.

Marat motioned for Charlotte to take the chair placed by his bath. She sat as requested, turning toward the open window, searching the still, hot summer air for what little breeze might chance to come her way. Her eyes began to tear, struggling against the stench of death and medicine. And in the gloom of evening’s waning light, Marat wrote down, one by one, his head bent over his writing table, the names of each of Charlotte’s beloved Girondin friends, then holed up in Caen.

Once finished, he raised his head. His blood-shot eyes met hers for the first time, and he proclaimed, hate dripping from his lips, “We’ll soon have them all guillotined in Paris!”

At that moment Charlotte remembered why she had come. She pulled a kitchen knife from the folds of her dress and stabbed Marat right through the heart. One blow was all it took. She felt the knife penetrate flesh, bone, muscle. Marat died almost instantly.

But it was not Charlotte who was martyred that day. On the contrary, it was Marat’s body that received a hero’s funeral. In one of the greatest propaganda events ever to take place in the history of the Reign of Terror, Marat was placed in a proper coffin, paraded through the streets of Paris to the sound of weeping citizens, and buried at the Pantheon. He might have died quietly in his bath. Instead, all he stood for – all that Charlotte loathed – was championed before thousands by the radical Jacobins.

In contrast, Charlotte was captured, tried, convicted and imprisoned at the Conciergerie, the antechamber to the guillotine. She lost not only her cause but also her head four days later, 17 July 1793, four years and four days after the symbolic debut of the peaceful Revolution she was attempting to save. Her remains were tossed, without ceremony, among those of the other victims of the Reign of Terror into an open, pestilent, public grave.

Targeting a dying man rather than the more powerful, and more ruthless, among the Revolutionary leadership, did Charlotte truly believe, as her farewell letter to the French people maintains, that “with my single act of violence I will bring peace to my Nation”?

Charlotte’s act of murder, rather than stopping the violence as she hoped, only unleashed more. A long shadow of doubt was cast over the remaining Girondin delegates to the National Convention. Already in trouble for standing against the execution of King Louis XVI, they were now believed by Maximilien Robespierre, deputy of the Committee for Public Safety, and the radical Jacobins to have been in cahoots with young Corday, even though she insisted that they were not. Indeed, their presumed collaboration was never proven. However, all 21 Girondin delegates were put to death, just as Marat had wanted, on 29 October 1793.

Marie Antoinette, Queen of France, would beat the 21 Girondins to the guillotine by a mere two weeks. Cousin Philippe Egalité, would follow them in November.

But as extremists and ideologues throughout history have learned, karma has a way of catching up with you. It took two years and 20,000 lives, but the French eventually realized, like Charlotte, that the promise of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity that the Revolution once represented had long since been lost. The most radical revolutionaries began to turn on each other. They, too, would meet their end at the guillotine, in a ritualized procession they would come to share with Corday.

On the afternoon of her beheading, Charlotte was taken to the Salle de la Toilette of the Conciergerie. Her thick, chestnut curls were cut off above her neck at the express wish of Sanson, the Revolution’s executioner. The only thing capable of slowing the guillotine blade was human hair, which could only result in excruciating pain for the condemned. Though a professional killer, Sanson was humane. Charlotte’s hair was gathered up and placed in a basket for safekeeping: the wife of the Concierge made an extra living creating wigs from the hair of the guillotine’s victims.

Charlotte’s hands were then tied behind her back, and she was escorted to the Carré des douze (Square of the twelve), a small, triangular courtyard behind the iron gate in the cours des femmes (the women’s courtyard) of the Conciergerie Prison. The condemned were held there on the day of their execution, twelve at a time. That’s how many fit in a tumbrel. The tumbrel made the round trip, from prison to guillotine, as many as three times a day.When the empty tumbrel arrived at the Conciergerie, a large bell was sounded from a pull chain in the main courtyard of the Palais de Justice, the Cour du Mai. Charlotte was then taken into the May Courtyard were a group of black-toothed women revolutionaries, les tricoteuses (knitter-women), thus called because they knitted clothes and bandages for the Revolutionary troops, heckled her mercilessly. Believed to be in the pay of the public prosecutor, Antoine-Quentin Fouquier-Tinville, they incited the crowd to humiliate all prisoners of the Revolution as they made their final voyage to the guillotine.

Charlotte was then loaded with the others like cattle into the open wooden tumbrel and taken to the Place de la Revolution to face her beheading. She was the only one among the twelve to wear a red chemise (dress), the sign of her crime of murder.

Witnesses say it poured with rain throughout Charlotte’s long journey to the Place de la Revolution. However, the weather would not scatter the crowd. No one wanted to miss the beheading of the murderer of Jean-Paul Marat. To do so might send a signal that you supported her actions.

The streets were so clogged with onlookers that it took two hours for the tumbrel carrying Charlotte Corday to reach its bloodstained destination. En route down the Rue Saint Honoré to the guillotine, people hurled insults, even stones, at the prisoners, further humiliating them in their final hours of life. Charlotte remained standing, calm and poised, throughout the ordeal.

From a window overlooking the procession, Robespierre, Camille Desmoulins and George Danton, all friends of Marat, watched her pass. That this would one day be their own fate was the furthest thing from their minds.

When the tumbrel finally reached the foot of the guillotine, the rain stopped. A purple sunset flooded the sky. Some among the twelve screamed and begged for mercy. Others struggled hopelessly to be free. Still others followed along, head cast downward, resigned. Only Charlotte mounted the scaffold steps without hesitation or assistance that day. She gave herself willingly to Sanson’s blade.

© Sarah Towle

Sarah Towle is Founder and Creative Director of Time Traveler Tours, mobile iTineraries that reveal history through the stories of characters who helped shape their time, enhanced with dash of interactive games. Charlotte Corday is the subject of the first of these new App tours, Beware Madame la Guillotine, A Revolutionary Tour of Paris, with which teens (12+) and adults can follow in the footsteps of this compelling historical figure for a “Revolutionary” and entertaining visit of Paris’ well-known and lesser-known sights. “Beware Madame la Guillotine” was chosen as a finalist for the World Youth and Student Travel Conference 2012 App Yap Contest.

France Revisited’s Revolutionary Charlotte Corday Contest

The first three people to answer the following two questions correctly will win a free download of Sarah Towle’s app tour “Beware Madame la Guillotine, A Revolutionary Tour of Paris” ($7.99 value).

Question 1: How many condemned typically fit in a tumbrel?

Question 2: Marat, Robespierre, Danton and other major figures of the French Revolution frequented Le Procope, now Paris’s oldest café still in existence. The desks of which two philosophers of the Enlightenment are found at Le Procope?

The contest has ended with three winners: Vince, Catt and Lesley.

The answers:

Twelve condemned could be carted to the guillotine in a tumbrel.

The desks of Voltaire and Rousseau are found at Le Procope.

Several people knew that Voltaire’s desk is found at Le Procope but couldn’t find the second. Here’s a photo of that second one, which belonged to Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Thanks to all those who submitted answers.

I got the first one and half of the second but stuck on the other half. You rascal!

MJ. Thanks for playing. Take a guess on the second one and send it in. GLK

Go for it, Mary Jo!

Gary, should we give them a hint?

Best,

Sarah

Yes – please a hint. T.

I’ve never been to Procope so don’t know the answer but I enjoyed the article and learned a lot. Merci.

Bonjour!

Love, love, love your website for its great travel resources and these fascinating tales from French history. OK, here goes: 12 condemned souls squeeze into a tumbrel. And Robespierre’s and Voltaire’s desks are at Procope. Oui?

Merci, Catt

Catt,

Thanks for reading France Revisited and for the kind words.

You’re close with the answers: two right but one needs some philosophical reconsideration. Try again.

Gary

We now have three our three winners: Vince, Catt and Lesley.

The winning answers are:

12 people could be carted to guillotine at a time in a tumbrel

The desks of philosophers Voltaire and Rousseau are found at the historical restaurant Le Procope.

Thanks to all those who participated. Stay tuned for other France Revisited contests.

Gary

So well-written. Fascinating to read.

Is there any truth to the story that the executioner slapped Charlotte’s (beheaded) face, that she then blushed. A scientist of the nobility headed himself to the same fate, noticed the blush. So he instructed a colleague to watch his execution and that he would blink for as long as he remained conscious. He blinked 14 times.

Bonjour Diane,

If interested in possible consciousness or neurological reactions after beheading, you should ask a neurologist or a neurosurgeon.

Here’s my take on the myth of the “blushing” and the “blinking”: Try to imagine the turmoil of a scene in which a beheaded head falls into a basket. Lots of blood. Then someone picks up the head and slaps it. A slap could bring blood closer to that cheek and/or the slapper could have had blood on his hand from picking up the head. In any case, “blush” doesn’t seem to be the right term for whatever someone may have seen. As to the 14 blinks, you don’t truly believe that someone about to be beheaded had a “colleague” nearby to count blinks, do you? In any case, “blink” would be the wrong term if indeed his eyes fluttered. The neurologist or neurosurgeon can better explain the possibility of a reddened cheek and fluttering eyes.

Let me know what you find out from the physicians.

Gary