While planning a trip to Provence a few years back my friend Sergio Cervetti urged me to seek out Mérindol, a town in the southern Luberon. He said it was a relatively obscure destination, but one that would connect me to his deepest roots in France. Having collaborated with Sergio, a composer, as librettist on two operas, I regarded his recommendation with respect and curiosity.

Sergio Cervetti is a native of Uruguay, but his mother was born in France of Waldensian ancestry. Persecuted for centuries in both France and Italy, the Waldensians–les Vaudois–were a sect founded in the 12th century by Pierre Valdès (or Valdo), a Catholic merchant from Lyon who relinquished his property and riches to preach an ideal life of devotion to Biblical teachings of poverty, simplicity, and non-violence.

Originally identifying themselves as Catholics, the “poor men of Lyon,” as Valdès and his followers came to be known, were declared heretics by the church for beliefs that are remarkably contemporary—such as a penchant for equality, disdain for clerical hierarchy, and acceptance of female preachers as early as the 15th century.

Because of the threat their radical ideas posed to the Church and Church-sponsored thrones, the Vaudois were chased and slaughtered throughout France and rural areas of Italy, where many fled in hopes of finding refuge. So great was public outcry in Europe in the 17th century that Oliver Cromwell made official appeals for an end to the slaughter, and poet John Milton wrote a sonnet, “On the Late Massacre in Piedmont” to protest and memorialize the horrific murder of hundreds of Vaudois in the Italian Alps in 1655.

The Waldensians eventually found tolerance and survival, at times, in ghetto-like pockets established in Germany, Switzerland, and Italy. Today, their descendents maintain their religious identity, and the largest contemporary community of the Vaudois is in Italy, where they were granted religious freedom in 1848. Some of the Vaudois eventually joined the legions of Europeans who immigrated to the Americas in search of religious tolerance and economic opportunity. Small, active communities exist today in Argentina, Uruguay, and in North America, particularly in Valdese, North Carolina, which takes its name from the Vaudois who settled there.

Mérindol, in the Vaucluse, is the site of a hilltop village whose inhabitants were massacred over a period of five days in 1545 in a crusade ordered by the French King Francois I and orchestrated locally by Jean Maynier d’Oppède, president of the parliament of Provence. The population was virtually exterminated, but it is said that some of the Vaudois of Mérindol survived by hiding in the dense mountains of the Luberon.

When my husband and I turned off the D973 road and drove through the modest, contemporary town at the base of the mountain, we had no idea how we would be touched by the hike up to the ancient village of the Vaudois. We found ourselves challenged by the climb, the sad ruins, and a view from the summit that must have been beloved by those who called the mountain home.

It was mid-afternoon when we began our ascent, and we were alone on the path until our return in the late and lingering dusk of Provence. “At Mérindol” describes our journey to the summit and to a spiritual connection with an intangible presence that we felt amidst the ruins. It is dedicated to the friend who led us there.

At Merindol

(for Sergio Cervetti)

The sun clings to the summit,

and blinks through dark trees

that spiral the hill.

We falter in stone and

growth of four hundred years.

Ahead is a ruin,

looking with shrouded eyes

for its generations.

Our feet pound in ascent.

Our companions are the wind

and punch of breath.

The shadowed twist of tree and earth

blinds us to all but tree and earth.

A dirt path opens to a riven wall.

We follow dirt and wall

bearing hard against gusts

that surge like feral spirits.

Remnants of parapets and corners

press into the acclivity–

carcass of village

blanched by sun and crusade.

We think we see the top, but there is more:

more fragments of wall and window

ghostly stairs, flesh-hewn for

rush of man and child to

the smell of bread on stone

a woman’s hand upon a door,

conversation across a sill,

fatigue of night,

the brace of morning.

Sorrows of path and village

yield to the summit and

ochre mountains, the bend

of the Durance through purple fields,

Alpilles to the south, and the sea.

Joy reaches beyond ghosts and martyrs

to hearts on a summer evening

and this sunset: assurance of

the divine in valley, sky, the walls of home.

Light bleeds through a crater in the last ruin.

Shadows sink at its base like souls

returning to the grave.

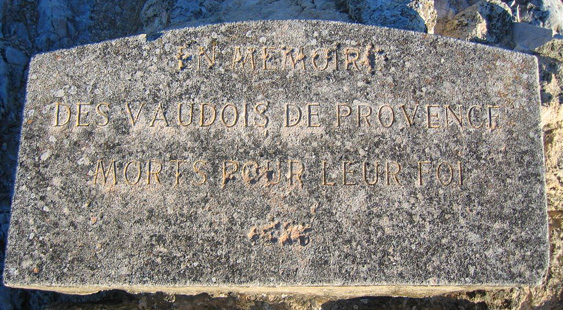

We read the timeline of Les Vaudois en Provence.

1545 mort pour leur foi

leur descendants affirms

flight to purple fields and the Durance,

ochre mountains, Alpilles to the south,

the sea, searching for the divine,

for home.

Winds of dusk calm to a breeze

and darkness looms.

Our feet move cautiously in descent,

spiraling the dirt path and stone wall

past life and loss, our

eyes on twist of tree and earth

guided by ghostly hands that

know the way.

© Elizabeth Esris

Elizabeth Esris is a teacher and writer. Her poetry has appeared in Wild River Review, Bucks County Writer, and Women Writers. She wrote the libretto for Elegy For A Prince with composer Sergio Cervetti, which premiered in excerpts at New York City Opera’s VOX Opera Showcase in 2007. She and Cervetti also collaborated on a one-act chamber opera, YUM!, a celebration of wine, food, and friendship. She teaches English and creative writing at Central Bucks High School South (Pennsylvania).

Your footsteps are mine: I see both the sorrow and the sunset. Very moving, Betty Lou!

There are a number of Waldensian settlements near the Luberon in Provence including la Roque d’Antheron up river, and on the south side of the Durance. Maps to la Roque’s “Waldensian Village” and “The Trail of Temples in the Luberon” may be downloaded from http://www.ville-laroquedantheron.fr – Nearby is the Abbaye de Silvacane (10th century) and the Agoult family chateau in Lourmarin.

Walter.

I figured that was your territory since it’s near the area that you covered in your recent biking article. Thanks for adding that information.

Gary

Thanks for the link! Religion weaves its way across France in such interesting ways.

Beautiful work, Elizabeth. I hope to read more from you.

Thank you, Daniel!

My name is Kenn Joubert; born in S.Afrca but of Huguenot origins. My family is traced back to La Motte d’Aigues on the Luberon hillside.

History says the Joubert family (possibly) we placed in the village which had been wiped out by the plague in the 1600s. I would like to know whether we were also Vaudois origin? Where can I find out.

I have visited the area in 1998 and loved it!

Thank you.

Kenn.

kvjoubert@shaw.ca

Kenn: I don’t have an answer for your, but your question interests me a great deal. In fact a quick Internet search of ” Huguenots” brought up a Wikipedia article which had an old print of the massacre of The Waldenesians at Merindol! I would never have expected to find Waldensians coupled with Huguenots, but it appears on many pages beyond the sketchy Wiki article. I am going to inquire of my friend Sergio, who is cited in the article. He may have done research on his ancestry in Provence. When I hear from him I will send a message to your personal website. In the meantime, perhaps other readers may have information. Let’s see where it goes.

All best,

Elizabeth